Religious Affiliation and Suicide Attempt

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Few studies have investigated the association between religion and suicide either in terms of Durkheim’s social integration hypothesis or the hypothesis of the regulative benefits of religion. The relationship between religion and suicide attempts has received even less attention. METHOD: Depressed inpatients (N=371) who reported belonging to one specific religion or described themselves as having no religious affiliation were compared in terms of their demographic and clinical characteristics. RESULTS: Religiously unaffiliated subjects had significantly more lifetime suicide attempts and more first-degree relatives who committed suicide than subjects who endorsed a religious affiliation. Unaffiliated subjects were younger, less often married, less often had children, and had less contact with family members. Furthermore, subjects with no religious affiliation perceived fewer reasons for living, particularly fewer moral objections to suicide. In terms of clinical characteristics, religiously unaffiliated subjects had more lifetime impulsivity, aggression, and past substance use disorder. No differences in the level of subjective and objective depression, hopelessness, or stressful life events were found. CONCLUSIONS: Religious affiliation is associated with less suicidal behavior in depressed inpatients. After other factors were controlled, it was found that greater moral objections to suicide and lower aggression level in religiously affiliated subjects may function as protective factors against suicide attempts. Further study about the influence of religious affiliation on aggressive behavior and how moral objections can reduce the probability of acting on suicidal thoughts may offer new therapeutic strategies in suicide prevention.

Suicide rates are lower in religious countries than in secular ones (1, 2). Some of this difference may be due to underreporting in religious countries because of concerns over stigma (3). Yet, some of the difference may be real, although it is not known whether the negative association between religion and suicide is due to its integrative benefits (such as social cohesion, as proposed by Durkheim in 1951 [4]) or to the moral imperatives of religious belief, given its prohibitions against suicidal behavior (1, 5–7). Most previous studies have been epidemiologic and have investigated the association between completed suicide and religion. An inverse relationship between religious commitment and suicidal ideation has also been reported (5, 8–10). However, reports regarding religious affiliation and suicide attempt are sparse. Morphew (11) compared 50 suicide attempters hospitalized after self-poisoning with respect to their religious beliefs and practices. He found no significant differences in terms of Catholic versus Protestant affiliation. Similarly, Malone et al. (12) reported that religious persuasion, defined as Catholic and non-Catholic, did not differ between suicide attempters and nonattempters. Kok (13) compared suicide attempt rates in Chinese, Malay, and Indian women in Singapore and concluded that the comparatively low rate of attempted suicide in Malay women was due to their religion, since Islam strictly forbids suicide.

Studies of religious commitment in general suggest a protective effect as well. In a sample of institutionalized chronically ill elderly, Nelson (14) showed that intensity of religious commitment was negatively associated with suicide gestures. In a cross-national study of 25 countries, Stack (1) concluded that protective effects were not due to any specific religious denomination per se but rather to a strong religious commitment to basic life-preserving values, beliefs, and practices that reduce rates of suicide.

Therefore, we examined factors associated with religious affiliation and nonaffiliation in depressed inpatients, generally considered to be at highest risk for a suicide attempt. We hypothesized that the religious subjects would report more moral objections to suicide as measured with the Reasons for Living Inventory (15). This instrument includes questions that reflect traditional religious beliefs: “I believe only God has the right to end a life,” “My religious beliefs forbid it,” “I am afraid of going to Hell,” and “I consider it morally wrong.” We examined the relationship between religious affiliation and social cohesion by examining the amount of time spent with relatives in religiously affiliated versus unaffiliated patients. To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the relationship between religious affiliation status and suicide attempts in a clinical sample.

Method

Subjects

Inpatients (N=371) who met DSM-III-R criteria for a current major depressive episode were entered into the study. The mean age of the sample was 36.8 years (SD=12.8), 40.4% (N=150) were female, and 78.2% (N=290) were white. Subjects were recruited at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic. Exclusion criteria were current substance or alcohol abuse, neurological illness, or other active medical conditions. All subjects gave written informed consent for the study as required by the Institutional Review Board.

DSM-III-R axis I psychiatric disorders were diagnosed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (16) and confirmed by a consensus conference led by experienced M.D.- or Ph.D.-level clinicians. Psychiatric symptoms were assessed with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (17), the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (excluding the suicide item) (18), the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (19), the Beck Depression Inventory (20), and the Beck Hopelessness Scale (21). Lifetime aggression, hostility, and impulsivity were measured with the Brown-Goodwin Aggression Inventory (22), Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (23), and the Barratt Impulsivity Scale (24). Stressful life events were assessed with the St. Paul-Ramsey Scale (unpublished 1978 instrument of A.E. Lumry). The Reasons for Living Inventory (12) was administered to assess protective factors. Social network assessments were made by using the “significant others” items from our baseline demographic form, which inquire about the persons with whom subjects spend the most time and how much time they spend. We chose these items as a proxy for social network assessment, since they reflect two important characteristics as described by Lin et al. (25): frequency of contact and network composition. In order to perform logistic regressions, we dichotomized the variable “significant others” as follows: family members (spouse, mother, father, sibling, offspring, grandparent, other relatives) and non-family members (roommate, friend, fiancée, other).

Lifetime history of suicide attempts was obtained from the Columbia Suicide History Form (26). A suicide attempt was defined as a self-destructive act with at least some intent to end one’s life. The highest level of suicidal ideation in the 2 weeks preceding the baseline assessment was measured by using the Scale for Suicide Ideation (27).

Statistical Methods

Pearson correlations, t tests, and chi-square analyses were used to identify correlated variables. Subjects who endorsed a religious affiliation and those who did not were compared in terms of demographic and clinical variables by using chi-square analyses for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. Backward stepwise regressions were conducted for the purpose of data reduction. One regression included all demographic variables that differed significantly between religiously affiliated and unaffiliated subjects as the independent variables and suicide attempt as the outcome variable. Similar analyses were conducted with the clinical variables that differed significantly between the two groups. A final model was subjected to logistic regression with suicide attempt as the outcome variable and religious affiliation as the independent variable after we controlled for moral objections to suicide and significant demographic and clinical factors selected in the data reduction regressions. A similar procedure was used for suicidal ideation, resulting in a final linear regression with suicidal ideation as the outcome variable.

In order to investigate whether moral objections to suicide mediate the relationship between suicidal behavior and religious affiliation, we used an established three-step procedure (28). First, we examined the bivariate association between religious affiliation and suicide attempt and whether the magnitude of this association was reduced when moral objections to suicide were controlled statistically. Second, we investigated whether religious affiliation was associated with moral objections to suicide. Finally, we determined whether moral objections to suicide were associated with suicide attempt after religious affiliation was controlled statistically. If all three conditions were met, it could be inferred that moral objections to suicide mediate the association between religious affiliation and suicide attempt.

Results

Two hundred ninety-five (79.5%) of the subjects had a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, and 76 (20.5%) had bipolar disorder, currently depressed. There were 189 subjects (50.9%) with a lifetime history of a suicide attempt. One hundred seventy-five (47.2%) had a history of substance use disorder. The mean clinical ratings were 20.1 (SD=6.2) on the Hamilton depression scale, 28.1 (SD=11.4) on the Beck Depression Inventory, and 36.3 (SD=8.1) on the BPRS. Among the subjects who reported a religious affiliation (N=305), the specific denominations endorsed were Catholicism (41.0%, N=125), Protestantism (28.5%, N=87), Judaism (17.4%, N=53), and other (13.1%, N=40).

Effect of Religious Affiliation in Subjects With Depression

Subjects with no religious affiliation were more often lifetime suicide attempters, reported more suicidal ideation, and were more likely to have first-degree relatives who had committed suicide than religiously affiliated subjects.

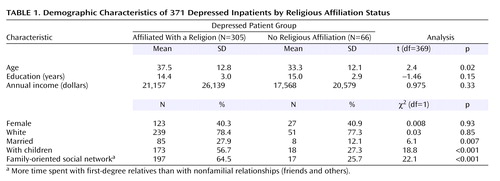

The religiously affiliated and unaffiliated subjects did not differ in terms of gender, race, education, or income. Religiously unaffiliated subjects were younger, less often married, and less often had children. Religiously affiliated subjects reported a more family-oriented social network, reflected in more time spent with first-degree relatives. In contrast, most unaffiliated subjects (74.3%) reported more nonfamilial relationships (friends and others) (Table 1).

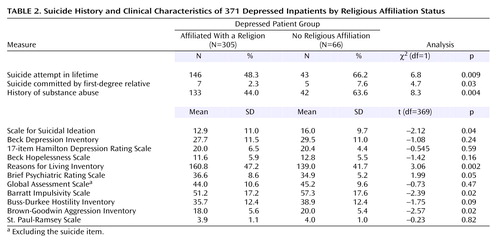

There were no differences between groups in the level of subjective depression (Beck Depression Inventory), objective depression (Hamilton depression scale), hopelessness (Beck Hopelessness Scale), life events (St. Paul-Ramsey Scale), or global functioning (GAS) (Table 2). Lower general psychopathology scores (BPRS) were found in the patients with no religious affiliation. Significantly higher lifetime scores for aggression (Brown-Goodwin Aggression Inventory) and impulsivity (Barratt Impulsivity Scale) but not hostility (Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory) were found in the religiously unaffiliated group. Furthermore, a history of substance use disorder was more common in the subjects with no religious affiliation (Table 2). Subjects with no religious affiliation also reported fewer perceived reasons for living (Reasons for Living Inventory). In particular, scores on three Reasons for Living Inventory subscales: responsibility to family (t=3.1, df=262, p=0.002), child-related concerns (t=2.6, df=253, p=0.008), and moral objections to suicide (t=4.7, df=97.6, p<0.001) were higher in the religiously affiliated group. The scores on other Reasons for Living Inventory subscales did not significantly differ between the two groups: survival and coping beliefs (t=1.83, df=261, p<0.07), fear of suicide (t=0.83, df=261, p<0.41), and fear of social disapproval (t=0.24, df=97, p<0.81).

Relationship Between Religious Affiliation and Suicide Attempts

A backward stepwise logistic regression showed that age (odds ratio=0.97, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.95 to 0.99; Wald χ2=7.84, p=0.005), but not marital status, parental status, or time spent with family, was significantly associated with suicide attempt status. With regard to clinical variables, only lifetime aggression (odds ratio=1.09, 95% CI=1.03 to 1.14; Wald χ2=9.83, p=0.002) and responsibility to family (odds ratio=0.93, 95% CI=0.91 to 0.97; Wald χ2=17.99, p<0.001) were significantly associated with suicide attempt status, whereas history of past substance use, lifetime impulsivity, general acute psychopathology as rated by the BPRS, and child-related concerns were not.

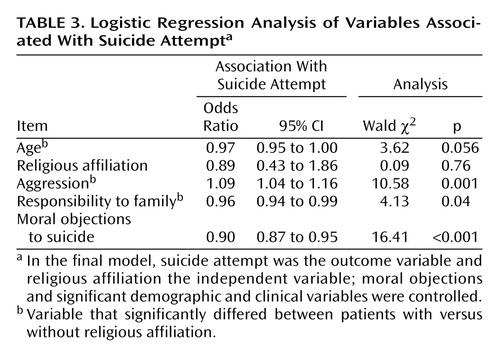

On the basis of these two data reduction regressions, a final model was tested with suicide attempt status as the outcome variable and age, aggression, responsibility to family, religious affiliation, and moral objections to suicide as the independent variables. Backward stepwise logistic regressions showed that low moral objections to suicide, high lifetime aggression levels, and less feeling of responsibility to family were significantly associated with suicide attempt, whereas religious affiliation per se and age were not (Table 3). Although the odds ratio for aggression and moral objections to suicide were low (1.09 and 0.90 respectively), the score ranges for these variables indicate a meaningful effect on risk for suicide attempt.

Of note, there was no significant correlation between moral objections to suicide and aggression level (r=–0.08, df=249, p<0.18). Also, when entered in a logistic backward conditional regression model with suicide attempt as a dependent variable, both variables remained significant and independent (moral objections to suicide: odds ratio=0.89, 95% CI=0.85 to 0.93 [[test statistic]=[value], p<0.001]; aggression: odds ratio=1.1, 95% CI=1.06 to 1.1 [[test statistic]=[value], p<0.001]).

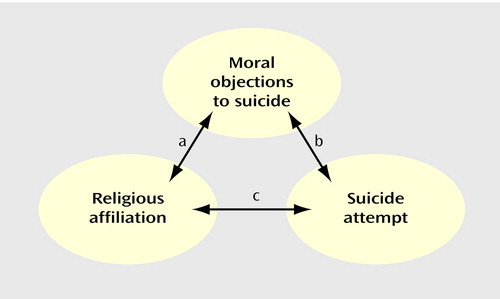

Moral objections to suicide mediated the association between religious affiliation and suicide attempt as all three stipulated conditions were met (28). First, religious affiliation was significantly associated with moral objections to suicide. Second, moral objections to suicide was significantly associated with suicide attempt when religious affiliation was statistically controlled. Third, the significant bivariate association between religious affiliation and suicide attempt did not remain significant when moral objections to suicide were controlled statistically (Figure 1).

Relationship Between Religious Affiliation and Suicidal Ideation

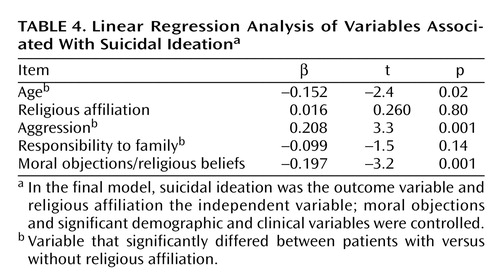

Linear stepwise regressions with suicidal ideation as the dependent variable showed that of the demographic variables, age was significant (β=–0.182, t=–2.9, p=0.003), whereas marital status, parental status, and social network were not. Of the clinical variables, linear stepwise regression analysis showed that aggression (β=0.218, t=3.6, p<0.001) and responsibility to family (β=–0.23, t=–3.7, p<0.001) were significant, whereas history of past substance abuse, BPRS score, impulsivity, and child-related concerns were not significant. The final model with suicidal ideation as the outcome variable and age, aggression, responsibility to family, religious affiliation, and moral objections to suicide as the independent variables revealed that high aggression scores, low moral objections to suicide, and younger age were significantly and independently associated with suicidal ideation. Religious affiliation and responsibility to family were not (Table 4).

Discussion

Kendler et al. (29) noted that religiosity is a prominent and complex aspect of human culture relatively neglected in comprehensive biopsychosocial models of psychopathology. Indeed, religious commitment to a few core life-saving beliefs may protect against suicide (1, 7, 30).

The main finding of this study was that religiously affiliated subjects were less likely to have a history of suicide attempts, the best predictor of future suicide or attempts (31). Moreover, greater moral objections to suicide that may represent traditional religious beliefs mediated the protective effect of religious affiliation against suicidal behavior in a clinical sample of depressed patients. Individuals with a religious affiliation also reported less suicidal ideation at the time of evaluation, despite comparable severity of depression, number of adverse life events, and severity of hopelessness. Of note, suicidal ideation, a risk factor for suicidal acts, has been found to be inversely related to religion (5, 8–10). Therefore, religion may provide a positive force that counteracts suicidal ideation in the face of depression, hopelessness, and stressful events.

Previous studies have not established an association between specific religious denomination (i.e., Catholic versus Protestant) and suicidal behavior. Our findings suggest that assessment of presence or absence of religious affiliation, regardless of denomination, may be more useful. Rather, lack of affiliation may be a risk factor for suicidal acts.

Suicidal behavior is related to aggressive and impulsive traits (30), and anger predicts future suicidal behavior in adolescent boys (32). Religiosity has been reported to be associated with lower hostility, less anger, and less aggressiveness (33, 34), which is consistent with our findings. Of note, aggression and moral objections to suicide were independently associated with suicidal behavior in this sample. Therefore, religious affiliation may affect suicidal behavior both by lowering aggression levels and independently through moral objections to suicide. Of interest is the fact that Boomsma et al. (35) found that in a twin sample, receiving a religious upbringing reduced the influence of genetic factors on disinhibition.

The relationship between religious affiliation and aggression in our study of depressed inpatients suggests therapeutic interventions for the prevention of deliberate self-harm. The potential for prevention by using therapeutic interventions aimed toward aggressive behaviors is strongly supported by reports that anger reduction leads to decreased parasuicidal behavior after dialectical behavioral therapy (36). Thus, supporting religious beliefs that patients find useful in coping with stress (33) and which may also reduce anger could be a useful tool in a therapeutic process that targets suicide prevention. Furthermore, patients who are wavering about their religious affiliation could receive support for their own ambivalently held beliefs and more specifically for their moral objections to suicide.

Religious commitment promotes social ties and reduces alienation (33). We found weaker family ties in religiously unaffiliated subjects, and family members are reported to be more likely to provide reliable emotional support, nurturance, and reassurance of worth (37). Our finding is consistent with reports about less dense social networks among atheists (38), although whether distancing from one’s family facilitates disaffiliation from the family’s religion or vice versa is not known.

The greatest protective effect of religion on suicide is reported to be present in subjects who have relatives and friends of the same religion (38). Although in our study social network was not independently related to suicidal behavior, stronger feelings of responsibility to family were found in religiously affiliated subjects, who were also more often parents and married. Responsibility to family was inversely related to acting on suicidal thoughts. Most religions stress the importance and value of family. Thus, consistent with previous reports (5, 6, 30), a commitment to a set of personal religious beliefs appears to be a more important factor against suicidal behavior than social cohesiveness per se. As noted by Pescosolido and Georgianna (38), religion’s role in suicidal behavior, operating through a social network mechanism, seems to be more complex than Durkheim’s social cohesion theory would suggest.

A tendency toward increased religiosity in older age (39) is consistent with the fact that the religious subjects in our study were older than nonreligious subjects (40). In our clinical sample, age was related to suicidal ideation but not to suicide attempt status.

Although it is not known whether there is causality involved in the association between suicide attempt and lack of religious affiliation, Kendler et al. (29) have argued that, in general, the effect of religious commitment on personal (mal)adjustment is stronger than the reverse. As Neeleman and Persaud (41) stated, psychiatric practice might be improved if an understanding of the role of religious beliefs in mental health and adaptation were integrated into research and practice. Yet, a recent survey of Canadian psychiatrists (42) showed that they did not assign importance to prayer above medication and psychotherapy in the case of suicidality, although they recognized its usefulness for other mental health difficulties. Indeed, psychiatrists are also reported to be less religious than the general population (43, 44), yet support of the patient’s spirituality has been deemed an ethical imperative, reflecting a physician’s commitment to the patient’s best interest (45).

This study has some limitations. For example, it did not assess religious upbringing, religious practice, or the level of personal devotion. Therefore, it is possible that depressed patients who stated that they were atheists or had no religion had abandoned religion as a consequence of depression or hopelessness. It is notable that hopelessness and depression scores were similar in the religious and nonreligious group but that the two groups differed strongly on perceived reasons for living. This suggests that some positive aspect of religious affiliation overcame the negative effects of depression, stressful life events, and hopelessness. Perhaps this was also manifested in the presence of less suicidal ideation.

Our study showed a relationship between religious affiliation status and suicide attempts in a clinical sample of depressed inpatients. It seems that the constellation of religious beliefs and lower aggression level, together with a higher threshold for suicidal thoughts in religiously affiliated depressed subjects, reduces risk for suicidal acts. Given the insufficient attention to patients’ religious attitudes by psychiatrists in general, support for the patient’s own religious affiliation could be an additional resource in psychiatric and psychotherapeutic treatments targeting suicidal acts.

|

|

|

|

Received Oct. 16, 2003; revision received Jan. 22, 2004; accepted Feb. 4, 2004. From the Department of Neuroscience, New York State Psychiatric Institute; and the Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Oquendo, Department of Neuroscience, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Dr., Unit Number 42, New York, NY 10032. This work was supported by NIMH grants MH-62185, MH-40695, and MH-48514 and funding from the Stanley Medical Research Institute.

Figure 1. Moral Objections to Suicide as Mediator of Religious Affiliation

aSignificant association between religious affiliation and moral objections to suicide (odds ratio=1.11, 95% CI=1.05 to 1.18; Wald χ2=14.07, p<0.001).

bSignificant association between moral objections to suicide and suicide attempt when religious affiliation was statistically controlled (adjusted odds ratio=0.90, 95% CI=0.87 to 0.94; Wald χ2=22.72, p<0.001).

cSignificant bivariate association between religious affiliation and suicide attempt that did not remain significant when moral objections to suicide were controlled statistically (adjusted odds ratio=1.3, 95% CI=0.71 to 2.6; Wald χ2=0.90, p<0.34).

1. Stack S: The effect of religious commitment on suicide: a cross-national analysis. J Health Soc Behav 1983; 24:362–374Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Breault KD: Suicide in America: a test of Durkheim’s theory of religious family integration, 1933–1980. AJS 1986; 92:628–656Google Scholar

3. Kelleher MJ, Chambers D, Corcoran P, Williamson E, Keeley HS: Religious sanctions and rates of suicide worldwide. Crisis 1998; 19:78–86Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Durkheim E: Suicide. Translated by Spaulding JA, Simpson G. New York, Free Press, 1951Google Scholar

5. Stack S, Lester D: The effect of religion on suicide ideation. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1991; 26:168–170Medline, Google Scholar

6. Neeleman J, Wessely S, Lewis G: Suicide acceptability in African- and white Americans: the role of religion. J Nerv Ment Dis 1998; 186:12–16Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Neeleman J, Halpern D, Leon D, Lewis G: Tolerance of suicide, religion, and suicide rates: an ecological and individual study in 19 Western countries. Psychol Med 1997; 27:1165–1171Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Paykel ES, Myers JK, Lindenthal JJ, Tanner J: Suicidal feelings in the general population: a prevalence study. Br J Psychiatry 1974; 124:460–469Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hovey JD: Religion and suicidal ideation in a sample of Latin American immigrants. Psychol Rep 1999; 85:171–177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Cook JM, Pearson JL, Thompson R, Black BS, Rabins PV: Suicidality in older African Americans: findings from the EPOCH study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002; 10:437–446Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Morphew JA: Religion and attempted suicide. Int J Soc Psychiatry 1968; 14:188–192Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Malone KM, Oquendo MA, Hass G, Ellis SP, Li S, Mann JJ: Protective factors against suicidal acts in major depression: reasons for living. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1084–1088Link, Google Scholar

13. Kok LP: Race, religion and female suicide attempters in Singapore. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1988; 23:236–239Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Nelson FL: Religiosity and self-destructive crises in the institutionalized elderly. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1977; 7:67–74Medline, Google Scholar

15. Linehan MM, Goodstein JL, Nielsen SL, Chiles JA: Reasons for staying alive when you are thinking of killing yourself: the Reasons for Living Inventory. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983; 51:276–286Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R—Patient Version 1.0 (SCID-P). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

17. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962; 10:799–812Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:766–771Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L: The measurement of pessimism: the Hopelessness Scale. J Consult Clin Psychol 1974; 42:861–865Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Brown GL, Goodwin FK, Ballenger JC, Goyer PF, Major LF: Aggression in human correlates with cerebrospinal fluid amine metabolites. Psychiatry Res 1979; 1:131–139Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Buss AH, Durkee A: An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostility. J Consult Psychol 1957; 21:343–349Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Barratt ES: Factor analysis of some psychometric measures of impulsiveness and anxiety. Psychol Rep 1965; 16:547–554Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Lin N, Ye X, Ensel WM: Social support and depressed mood: a structural analysis. J Health Soc Behav 1999; 40:344–359Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Oquendo MA, Halberstam B, Mann JJ: Risk factors for suicidal behavior: utility and limitations of research instruments, in Standardized Evaluation in Clinical Practice. Edited by First MB. Arlington, Va, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2003, pp 103–130Google Scholar

27. Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A: Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1979; 47:343–352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Bolger N: Data analysis in social psychology, in Handbook of Social Psychology. Edited by Gilbert D, Fiske ST, Lindzey G. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1997, pp 233–265Google Scholar

29. Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Prescott CA: Religion, psychopathology, and substance use and abuse: a multimeasure, genetic-epidemiologic study. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:322–329Link, Google Scholar

30. Greening L, Stoppelbein L: Religiosity, attributional style, and social support as psychosocial buffers for African American and white adolescents’ perceived risk for suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2002; 32:404–417Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Leon AC, Friedman RA, Sweeney JA, Brown RP, Mann JJ: Statistical issues in the identification of risk factors for suicidal behavior: the application of survival analysis. Psychiatry Res 1990; 31:99–108Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Goldney RD, Winefield A, Saebel J, Winefield H, Tiggeman M: Anger, suicidal ideation, and attempted suicide: a prospective study. Compr Psychiatry 1997; 38:264–268Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Koenig HG, McCullough ME, Larson DB: Handbook of Religion and Health. New York, Oxford University Press, 2001Google Scholar

34. Storch EA, Storch JB: Intrinsic religiosity and aggression in a sample of intercollegiate athletes. Psychol Rep 2002; 91:1041–1042Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Boomsma DI, de Geus EJ, van Baal GC, Koopmans JR: A religious upbringing reduces the influence of genetic factors on disinhibition: evidence for interaction between genotype and environment on personality. Twin Res 1999; 2:115–125Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Linehan MM, Heard HL: Impact of treatment accessibility on clinical course of parasuicidal patients: reply. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:157–158Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Walls CT, Zarit SH: Informal support from black churches and the well-being of elderly blacks. Gerontologist 1991; 31:490–495Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Pescosolido BA, Georgianna S: Durkheim, suicide and religion: toward a network theory of suicide. Am Sociol Rev 1989; 54:33–48Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Clarke CS, Bannon FJ, Denihan MB: Suicide and religiosity-Masaryk’s theory revisited. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2003; 38:502–506Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Hunsberger B: Religion, age, life satisfaction and perceived sources of religiousness: a study of older persons. J Gerontol 1985; 40:615–620Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Neeleman J, Persaud R: Why do psychiatrists neglect religion? Br J Med Psychol 1995; 68:169–178Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Baetz M, Larson DB, Marcoux G, Jokic R, Bowen R: Religious psychiatry: the Canadian experience. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002; 190:557–559Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Galanter M, Larson D, Rubenstone E: Christian Psychiatry: the impact of evangelical belief on clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:90–95Link, Google Scholar

44. Neeleman J, King MB: Psychiatrists’ religious attitudes in relation to their clinical practice: a survey of 231 psychiatrists. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1993; 88:420–424Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Post SG, Puchalski CM, Larson DB: Physicians and patient spirituality: professional boundaries, competency, and ethics. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132:578–583Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar