Use of Antidepressants Among Elderly Subjects: Trends and Contributing Factors

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors assessed changes over time in antidepressant utilization among elderly subjects regarding the prevalence of antidepressant users, shifts in prescription patterns, and related financial implications. METHOD: The authors conducted a population-based study of more than 1.4 million Ontario residents aged 65 years or older. Cross-sectional data regarding annual antidepressant utilization were obtained from administrative databases for 1993 to 1997. Time series analysis was used to assess trends over time and to make future projections. RESULTS: The proportion of antidepressant users increased from 9.3% of the elderly population in 1993 to 11.5% in 1997. Prescriptions for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) accounted for 9.6% of antidepressant prescriptions dispensed in the first 30 days of 1993 and 45.1% of those dispensed by the last 30 days of 1997 and were projected to increase to approximately 56% by the end of 2000. Prescriptions for tricyclic antidepressants fell from 79.0% in the first 30 days of 1993 to 43.1% by the last 30 days of 1997 and were projected to decline to approximately 28% by the end of 2000. Annual antidepressant costs (in Canadian dollars) increased by 150%, from $10.8 million in 1993 to $27.0 million in 1997. Population shifts and an increase in the prevalence of antidepressant users accounted for at least 20% of this increase, whereas the prescribing transition from tricyclic antidepressants to SSRIs accounted for at least 61% of the increase. CONCLUSIONS: The introduction of SSRIs has had a substantial financial impact at the drug utilization level. Future research should address the appropriate balancing of the cost of newer agents versus their ostensible advantages.

In the past 15 years, interest and activity regarding major depression have increased substantially. A number of studies documenting the low treatment rates (1–3) and severe consequences of major depression (4, 5) have led to numerous efforts to increase awareness and enhance treatment of the disorder. Such efforts include interventions in public education (such as the national and local Public Education Campaign on Clinical Depression of the National Mental Health Association in April 1993), the publication of treatment guidelines by major agencies (6, 7), increased funding for research, and a parallel effort by the pharmaceutical industry to encourage treatment by the energetic marketing of numerous new medications. More recently, several new antidepressants have entered the market, offering similar rates of treatment success but ostensibly fewer side effects than well-established medications such as tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) (8–10).

At the same time, there have been two other major developments: 1) an increase in the proportion of elderly residents among the general population and 2) further reliance on health care coverage by government agencies at a time of fiscal restraint. The search for improved treatment will inevitably be balanced against many competing demands for resources, necessitating a careful study of the costs and benefits—financial and clinical—of any particular therapeutic intervention.

Measuring such costs and benefits among elderly subjects involves looking at a specific segment of this population, examining the use of antidepressants within this group, and assigning clinical and financial costs to treatment. Before conducting such a comprehensive analysis, it is crucial to have antidepressant utilization information to determine if there is a reason for future clinical and financial concern on the basis of trends in antidepressant use. Rates of antidepressant use have been steadily increasing, and these drugs are now among the most widely prescribed in North America, exceeding the number of prescriptions of other psychotropic medications such as anxiolytics and hypnotics (11–13). Such high use comes not only from increasing treatment of depression but also from the expanded use of antidepressants to treat related disorders, particularly anxiety disorders (14). The combined effect of expanded use and the introduction of newer, more expensive compounds would be expected to be substantial and of great interest to policy makers, government, treatment providers, and consumers.

With these considerations in mind, we sought the answers to questions regarding changes in the utilization of antidepressants among 1.4 million elderly residents of Ontario, Canada, from 1993 to 1997. We asked five questions: 1) has the prevalence of antidepressant use changed over time; 2) how has the use of traditional antidepressants (tricyclic antidepressants and MAOIs) changed with the introduction of newer agents (i.e., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]); 3) what are the drug expenditure implications of the change; 4) what are the future implications of recent prescribing trends; and 5) what are the major contributing factors to changes in drug utilization expenditures?

METHOD

Study Design and Patient Population

A population-based study was conducted with the use of a cross-sectional series of data for annual antidepressant utilization from 1993 to 1997. All community-dwelling residents of the province of Ontario aged 65 years or older were included.

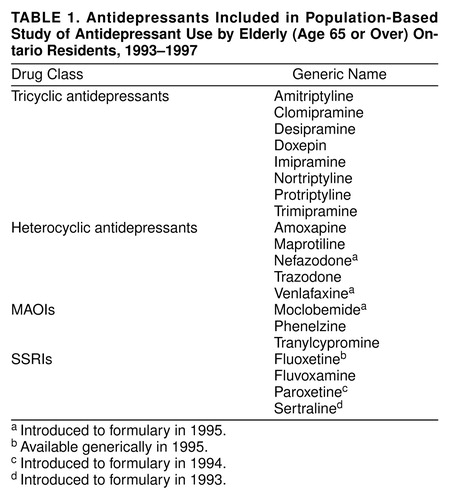

Data Sources

Drug utilization information was obtained from the Ontario Drug Benefits database, which is a provincial administrative database maintained by the Ontario Ministry of Health. It contains drug utilization information, including drug identification numbers, dates of prescriptions, and scrambled unique health care numbers for residents of Ontario age 65 or older. The Ontario Drug Benefits database is used by the Ontario government to pay pharmacy claims; claims have been submitted electronically since 1993. The database has been shown to be of high quality. Researchers using this particular database have found that there is very little missing information (15), consistent with other studies that have found less than 1% of the basic information on patients missing from various provincial drug plan databases (16–20). The specific antidepressant medications found in the database are outlined in table 1.

The Registered Persons Database, maintained by the Ontario Ministry of Health, contains demographic information and unique health care numbers for all individuals eligible for provincial health insurance schemes. (The Registered Persons Database and the Ontario Drug Benefits database are linked by unique patient identification numbers that are scrambled to protect patient confidentiality.) Statistics Canada census data provided the number of elderly residents in Ontario and their gender and age category designations on July 1 of each year.

Study Definitions

To assess whether changes in the prevalence of antidepressant use among elderly subjects were a reflection of changes in prescribing patterns promoting greater prescription medication use in general, the proportion of antidepressant users was compared with the proportion of prescription medication users for each year studied. An antidepressant user was defined as an elderly resident who had at least one prescription for an antidepressant medication filled (table 1). A prescription medication user was defined as an elderly resident who had at least one prescription for any medication filled.

The cost of antidepressant therapy was defined as the manufacturer’s ingredient cost plus 10%, as obtained from the Ontario Drug Benefits formulary, exclusive of dispensing and additional mark-up fees. This cost is equivalent to the acquisition cost of the medication to the pharmacy. Given the differences in copayment strategies available for patients and the poor generalizability of costs to specific health care plans, the manufacturer’s ingredient cost was selected in favor of cost to the patient or cost to the health care plan. All costs were expressed in constant 1997 dollars (Canadian).

For the purpose of determining the driving factors of the drug costs, the total cost of antidepressants was defined as the product of the number of antidepressant prescriptions dispensed and the average cost per antidepressant prescription. The number of antidepressant prescriptions dispensed is a function of shifts in the total population, the proportion of people treated with antidepressants, and the average number of antidepressant prescriptions per antidepressant user. The average cost per antidepressant prescription was defined as the sum of the products of the percentage of antidepressant prescriptions attributable to each drug class and the respective average cost per prescription.

Statistical Analysis

Since census data were available on an annual basis, only single summary measures for the prevalence of antidepressant and prescription medication use could be obtained for each of the years assessed. The Spearman rank-order correlation was used as a rough indicator of the presence of linear trends for these estimates.

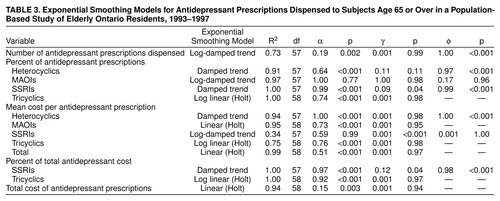

To adequately assess trends in the prescribing patterns of various classes of antidepressants over time and their respective costs, annual data for these variables were divided into equal 30-day periods from 1993 through 1997. Time series analysis (21) was conducted by using exponential smoothing models to assess trends. Observations with a temporal sequence were often autocorrelated (i.e., the value at time x is affected by the value at time x – 1). As a result, the error terms were not independent, making simple regression inappropriate for their analysis. Time series analysis is a collection of techniques for modeling autocorrelation in temporally sequenced data (21). Numerous smoothing models were fit to the data by using the SAS/ETS software package for Windows, Version 6.11 (SAS Institute, Inc.). The level (α), trend (γ), damping (ϕ), and seasonality (δ) smoothing weights were set to optimize the fit of the model to the data.

The statistical significance of the smoothing weights was assessed by dividing the parameter estimate by its standard error and comparing the resultant z statistic with a normal probability table. The standard errors associated with the smoothing weights were calculated from the Hessian matrix of the sum of squared one-step-ahead prediction errors with respect to the smoothing weights used in the optimization process (22). The model fit was assessed by using the R2 statistic, and the model with the best fit was selected for forecasting. Stationarity was assessed by using the autocorrelation function and the augmented Dickey-Fuller test (23). The autocorrelation, partial autocorrelation, and inverse autocorrelation functions were assessed for model parameter appropriateness and seasonality. The presence of white noise was assessed by examining the autocorrelations at various lags by using the Ljung-Box chi-square statistic (24).

Variance analysis (25) was used to quantify the contribution of the driving factors to the total cost of prescriptions by using annual data from 1993 to 1997. This simple tool for analysis is commonly used in the management sciences to assess the percentage change in the outcome of interest that is due to the change in an explanatory variable.

RESULTS

Population and Treatment Prevalence

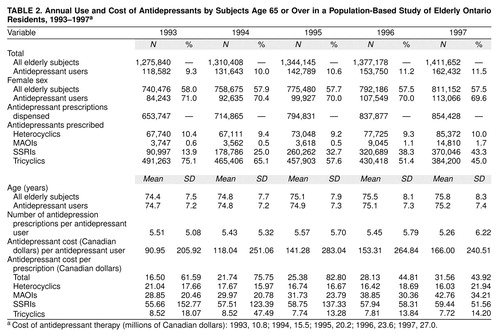

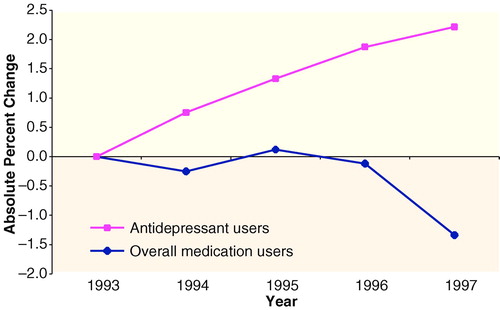

The elderly population in Ontario increased by approximately 10%, from 1.28 million in 1993 to 1.41 million in 1997 (table 2). The proportion of elderly subjects using an antidepressant increased by 24.0%, from 9.3% in 1993 to 11.5% in 1997. This change was not reflective of changes in overall prescribing patterns regarding elderly subjects. The proportion of elderly subjects receiving any medication prescription was fairly constant, approximately 90% for most years studied (figure 1) (r=–0.5, N=5, p=0.39), and actually decreased in 1997.

Change in Prescription Patterns Over Time

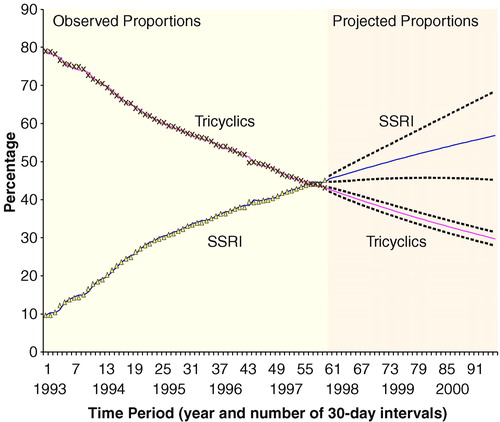

The greatest shifts in prescribing patterns occurred with the SSRI and tricyclic antidepressant drug classes (figure 2, table 2). The SSRIs accounted for 9.6% of the antidepressant prescriptions dispensed in the first 30 days of 1993 and rose to 45.1% by the last 30 days of 1997. Conversely, the percentage of prescriptions for tricyclic antidepressants fell from 79.0% in the first 30 days 1993 to 43.1% by the last 30 days of 1997. The percentage of prescriptions for heterocyclic antidepressants fluctuated between 1993 and 1997, whereas the percentage of prescriptions for MAOIs increased from 1996 to 1997. If these trends continued, it was projected that the heterocyclic, MAOI, SSRI, and tricyclic antidepressant classes would capture approximately 11% (95% confidence interval [CI]=8.2%–13.8%), 3% (95% CI=0.2%–13.6%), 57% (95% CI=45.2%–68.5%), and 30% (95% CI=28.0%–31.5%), respectively, of the antidepressant prescription market by the last 30 days of 2000. Annually, the proportion of antidepressant prescriptions attributable to heterocyclic and tricyclic antidepressants dropped from 1993 to 1997 (table 2). The proportion of antidepressant prescriptions rose for MAOIs and SSRIs from 1993 to 1997 (table 2). The projected proportions for 2000 were similar to those in the 30-day analysis.

Drug Use and Expenditures

Number of Antidepressant Prescriptions Dispensed

The number of antidepressant prescriptions dispensed in a 30-day period rose by approximately 50%, from 50,586 in the first 30 days of 1993 to 75,713 by the last 30 days of 1997, and was projected to increase by approximately 74%, to 88,269 (95% CI=73,816–104,715) by the last 30 days of 2000. In annual terms, the number of prescriptions dispensed increased by 31% (table 2), and was projected to increase to over 1 million by 2000. This represents an increase from approximately 51 antidepressant prescriptions per 100 elderly residents in Ontario in 1993 to 61 prescriptions per 100 elderly residents in 1997. The average number of antidepressant prescriptions fluctuated around 5.49 per antidepressant user per year (r=–0.5, N=5, p=0.39) (table 2).

Average Cost Per Antidepressant Prescription

The 30-day average cost per antidepressant prescription increased by approximately 118%, from $15.07 (in Canadian dollars) in the first 30 days of 1993 to $32.82 by the last 30 days of 1997, and was projected to increase by approximately 190% to $43.77 (95% CI=$40.40–$47.15) by the last 30 days of 2000. In annual terms, the average cost per antidepressant prescription increased by approximately 91% from 1993 to 1997 and was projected to exceed $42 by the end of 2000.

Several trends were noted with respect to the class-specific average cost per antidepressant prescription. The average cost per prescription for heterocyclic antidepressants dropped by approximately 25%, from $21.37 (in Canadian dollars) in the first 30 days of 1993 to $16.05 by the last 30 days of 1997, and was projected to drop approximately 37% to $13.42 (95% CI=$7.67–$19.16) by the last 30 days of 2000. The average cost per prescription for MAOIs, on the other hand, significantly increased by 51%, from $28.96 in the first 30 days of 1993 to $43.80 by the last 30 days of 1997, and was projected to increase approximately 87% to $54.09 (95% CI=$43.12–$65.06) by the last 30 days of 2000. The average cost per prescription for the SSRIs did not change substantially, from $60.11 in the first 30 days of 1993 to $60.27 by the last 30 days of 1997, and was projected to remain steady at $60.64 (95% CI=$48.33–$75.13) during the last 30 days of 2000. The average cost per prescription for the tricyclic antidepressants experienced a moderate drop of 11% from $8.64 in the first 30 days of 1993 to $7.65 in the last 30 days of 1997, and was projected to drop approximately 17% to $7.13 (95% CI=$5.54–$9.04) by the last 30 days of 2000.

Total Antidepressant Cost

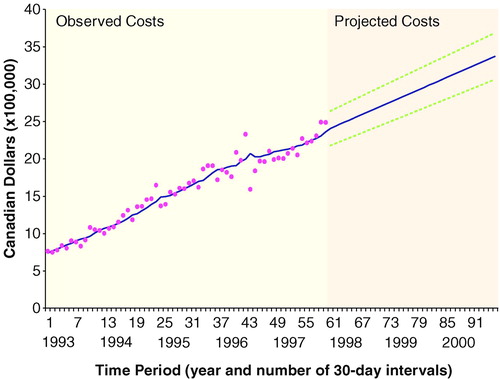

The 30-day total cost of antidepressant therapy rose steadily throughout the period 1993–1997. Total antidepressant cost increased by 228%, from $0.76 million in the first 30 days of 1993 to $2.49 million by the last 30 days of 1997 (in Canadian dollars), and was projected to increase approximately 347% to $3.4 million (95% CI=$3.06–$3.69 million) (figure 3) by the last 30 days of 2000. In annual terms, the total cost of antidepressant therapy increased by 150% (table 2) and was projected to exceed $38 million by 2000. This represents an increase in annual antidepressant cost from approximately $8.45 in 1993 to $19.10 per elderly Ontario resident in 1997.

Driving Factors for Antidepressant Drug Expenditures

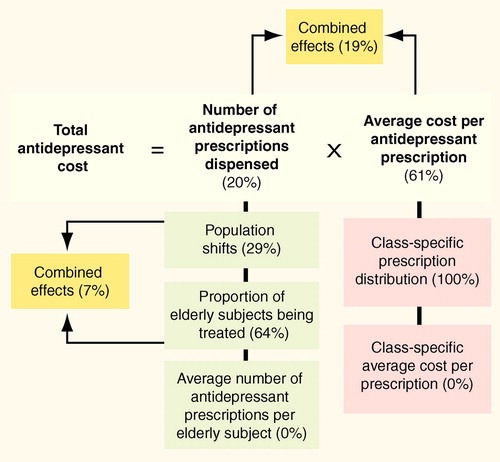

The increase in the number of antidepressant prescriptions dispensed independently accounted for approximately 20% of the increase in total antidepressant cost (figure 4). Approximately 29% of this increase in antidepressant prescriptions was, in turn, independently driven by an increase in population, whereas 64% of this increase was independently attributable to an increase in the proportion of elderly subjects receiving an antidepressant. The combined effect of the increasing elderly population and the increasing proportion receiving an antidepressant accounted for the remaining 7% of the increase in the number of antidepressant prescriptions dispensed.

The average cost per antidepressant prescription independently accounted for approximately 61% of the increase in total antidepressant cost. The class-specific shifts in the proportions of antidepressants dispensed accounted for 100% of the increase in the average cost per antidepressant prescription. The combined effect of the increase in the number of antidepressant prescriptions dispensed and the increase in the average cost per antidepressant prescription accounted for 19% of the increase in total antidepressant cost.

Market Share of SSRIs and Tricyclics

SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants accounted for the greatest proportions of antidepressant costs, given the large proportion of prescriptions written for these classes. The proportion of total antidepressant costs attributable to SSRIs increased substantially, from 38% in the first 30 days of 1993 to 83% by the last 30 days of 1997, and was projected to increase to approximately 88% (95% CI=59%–100%) by the last 30 days of 2000. Conversely, the proportion of total antidepressant cost attributable to the tricyclic antidepressants dropped from 45% in the first 30 days of 1993 to 10% by the last 30 days of 1997 and was projected to fall further to approximately 4.0% (95% CI=2.9%–5.4%) by the last 30 days of 2000.

DISCUSSION

Our study sought the answers to a series of questions regarding the evolution of antidepressant utilization in a population of elderly subjects by using, to the best of our knowledge, the largest sample reported to date in the literature. Well over 1 million elderly residents from Ontario, Canada, were included in an analysis of the increase in antidepressant utilization, shifts in prescribing patterns, resultant cost implications, and projections for future financial impacts. From 1993 to 1997, significant and consistent increases in the number of antidepressant users were observed each year, resulting in a relative increase of approximately 24%. This translates to approximately 32,000 more elderly residents being treated with antidepressants in 1997 than in 1993, independent of the increase in population. These changes are striking since they occurred at a time when overall use of any type of medication was fairly constant, if not declining. In consideration of the high rates of undertreatment of psychiatric disorders in general (1, 26), and mood disorders in particular (2, 3, 27, 28), such an increase likely represents an effort to improve the treatment of mood and related anxiety disorders among elderly patients. These findings suggest that efforts to improve health by using treatments with established efficacy such as antidepressants are proving successful.

Concomitant with an increase in the use of antidepressants was a substantial shift in prescribing practices. The use of SSRIs more than quadrupled in the 5-year observation period, and SSRI prescriptions were projected to capture approximately 57% of the market for antidepressant prescriptions by the last 30 days of 2000. Simultaneously, the use of tricyclic antidepressants fell by almost one-half, and prescriptions for tricyclic antidepressants were projected to capture a market share of approximately 30% by the last 30 days of 2000. Such a dramatic shift raises important questions from clinical and financial perspectives. From a clinical perspective, lower burdens of adverse effects, in particular, have been emphasized as a rationale for the use of SSRIs. However, several meta-analyses have questioned this perception (8–10), clarifying that while the adverse event profiles certainly differ between tricyclic antidepressants and SSRIs, the total incidence of adverse events may actually be similar—simultaneously reaffirming the equivalent therapeutic efficacy of the antidepressant classes. Furthermore, in considering the studies of late-life depression in which tricyclic antidepressants and SSRIs were compared, the tricyclic antidepressants used were almost always tertiary amine tricyclic antidepressants such as imipramine and amitriptyline (29), agents that should not generally be used in elderly subjects for the treatment of mood disorders (30). A more honest comparison of the two classes would compare SSRIs against secondary amine tricyclic antidepressants such as nortriptyline. In fact, a single study that compared an SSRI (sertraline) with a secondary amine tricyclic antidepressant (nortriptyline) among elderly patients (29) found both drugs to be equally efficacious and well tolerated. Important aspects that factor into the clinical decision to use SSRIs involve the easier dose titration and greater safety of these agents in an overdose (31). No consensus exists on how to reconcile these concerns with other factors, but it must be acknowledged as a significant determinant of prescribing practices.

In addition to the clinical implications of the use of particular drug classes, the financial implications must be weighed. In our study, antidepressant expenditures nearly tripled from the first 30 days of 1993 to the last 30 days of 1997 and were projected to nearly quadruple by the last 30 days of 2000. Some costs are unavoidable, namely increases in the prevalence of antidepressant use and the proportion of elderly patients in society, which accounted for at least 20% of the increase in cost during our study period. Health care planners and government must constantly balance providing expensive procedures against the cost of denying other treatments, a dilemma most dramatically highlighted by decisions such as choosing not to fund organ transplants in order to fund more immunizations in children (32). Our study found tremendous cost implications in the shift from tricyclic antidepressants to SSRIs, with SSRIs expected to account for 88% of all antidepressant costs by the last 30 days of 2000. In view of the ostensible clinical advantages of these agents, vigorous debate about the cost-effectiveness of SSRIs is indicated.

Several events during the study period may have affected the results of the study. Various antidepressants were introduced to formulary at different times throughout the study period, concurrent with the availability of generic fluoxetine (table 1). A copayment plan was introduced for all elderly residents of Ontario in July 1996 and may have affected subsequent utilization. The observed outcome of this intervention was increased utilization immediately before implementation of the copayment plan, decreased utilization immediately following its implementation, and stabilization shortly thereafter. Consequentially, the 95% CIs for the projections may have been narrower had this intervention not imparted such pronounced variability. These events are typical in the real world, and no precautions were taken to adjust for these effects. Since these events were specific to our population, any inferences regarding trends in cost must be made cautiously. Furthermore, the health care system in Ontario is a universal, primarily fee-for-service system in which cost-containment priorities with respect to prescription patterns may be different from those in other environments.

The financial results were expressed as the manufacturer’s ingredient cost in constant 1997 dollars (Canadian). Although differences in currencies and base-year pricing may lead to different results, the overall conclusions still hold. Floor and ceiling effects, however, were not captured by the statistical analyses. The data were not standardized with respect to age and gender since no significant shifts were observed during the study period (table 3) and the presentation of actual data was favored.

Our findings, despite the stated limitations, are striking in both positive and negative directions. Our most positive finding shows increases in the use of previously underutilized and effective medical treatments, demonstrated by the increasing proportion of elderly residents using antidepressants. Our most disturbing findings suggest that massive changes in prescribing practices are occurring in the absence of major efforts to conduct proper cost-effectiveness analyses. Even in the clinical realm, little relevant data exist to gauge the specific clinical benefits, risks, and medical complications of SSRIs versus tricyclic antidepressants. In the financial realm, we documented the substantial implications of the shift in prescribing practices. Future research should investigate the specific clinical benefits of treatment with each class of antidepressant and attempt to engage debate about the appropriate balancing of costs of the newer agents with their ostensible advantages.

Received March 26, 1999; revision received Aug. 30, 1999; accepted Sept. 30, 1999From the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto; the Department of Family and Community Medicine, Health Sciences Centre, Sunnybrook and Women’s College, Toronto; the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Toronto; and the Departments of Psychiatry and Public Health Sciences, the Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto. Address reprint requests to Dr. Mamdani, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, 2075 Bayview Ave., #G215, Toronto, Ont. M4N 3M5, Canada; [email protected] (e-mail).

|

|

|

FIGURE 1. Changes in the Proportion of Subjects Age 65 or Over Using Antidepressants and Overall Medication Users in a Population-Based Study of Elderly Ontario Residents, 1993–1997a

aBaseline year 1993 prevalence estimates: antidepressant users=9.3%; overall medication users=91.1%.

FIGURE 2. Changes in the Proportions of Antidepressant Prescriptions Attributable to SSRIs and to Tricyclic Antidepressants in a Population-Based Study of Elderly Ontario Residents, 1993–1997a

aSolid lines to the right of the vertical division represent the best estimate of the projected proportions after 1997. The dotted lines represent 95% CIs around these projected estimates.

FIGURE 3. Trends in Total Antidepressant Cost (in Canadian Dollars) in a Population-Based Study of Elderly Ontario Residents, 1993–1997a

aSolid line to the right of the vertical division represents the best estimate of the projected costs after 1997. The dotted lines represent 95% CIs around these projected estimates.

FIGURE 4. Variance Analysis of Antidepressant Cost Determinants in a Population-Based Study of Elderly Ontario Residents, 1993–1997

1. Parikh SV, Lin E, Lesage AD: Mental health treatment in Ontario: selected comparisons between the primary care and specialty sectors. Can J Psychiatry 1997; 42:929–934Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Keller MB, Harrison W, Fawcett JA, Gelenberg A, Hirschfeld RM, Klein D, Kocsis JH, McCullough JP, Rush AJ, Schatzberg A: Treatment of chronic depression with sertraline and imipramine: preliminary blinded response rates and high rates of undertreatment in the community. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995; 31:205–212Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hirschfeld RM, Keller MB, Panico S, Arons BS, Barlow D, Davidoff F, Endicott J, Froom J, Goldstein M, Gorman JM, Marek RG, Maurer TA, Meyer R, Phillips K, Ross J, Schwenk TL, Sharfstein SS, Thase ME, Wyatt RJ: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 1997; 277:333–340Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Roose SP, Glassman AH, Walsh BT, Woodring S, Vital-Herne J: Depression, delusions, and suicide. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:1159–1162Google Scholar

5. Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, Greenberg PE: Economics of Depression: A Summary and Review Prepared for the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association–Sponsored Consensus on the Undertreatment of Depression. Chicago, NDMDA, Jan 17–18, 1996Google Scholar

6. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatment (CANMAT): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Pharmacological Treatment of Depression, 1st ed. Toronto, CANMAT, 1999Google Scholar

7. Depression in Primary Care, vol 2: Treatment of Major Depression: Clinical Practice Guideline 5. Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1993Google Scholar

8. Steffens DC, Krishnan KR, Helms MJ: Are SSRIs better than TCAs? comparison of SSRIs and TCAs: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety 1997; 6:10–18Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Trindale E, Menon D, Topfer L, Coloma C: Adverse effects associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis. Can Med Assoc J 1998; 159:1245–1252Google Scholar

10. Anderson IM, Tomenson BM: Treatment discontinuation with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors compared with tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis. BMJ 1995; 310:1433–1438Google Scholar

11. Huszonek JJ, Dewan MJ, Koss M, Hardoby WJ, Ispahani A: Antidepressant side effects and physician prescribing patterns. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1993; 5:7–11Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Egberts ACG, Leufkens HGM, Hofman A, Hoes AW: Incidence of antidepressant drug use in older adults and association with chronic diseases: the Rotterdam Study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 12:217–223Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Pincus HA, Tanielian TL, Marcus SC, Olfson M, Zarin DA, Thompson J, Magno Zito J: Prescribing trends in psychotropic medications: primary care, psychiatry, and other medical specialties. JAMA 1998; 279:526–531Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Streator SE, Moss JT Jr: Identification of off-label antidepressant use and costs in a network model HMO. Drug Benefit Trends 1997; 9:42, 48–50, 55–56Google Scholar

15. Williams JI, Young W: A summary of studies on the quality of health care administrative databases in Canada, in Patterns of Health Care in Ontario: The ICES Practice Atlas, 2nd ed. Edited by Goel V, Williams JI, Anderson GM, Blackstein-Hirsh P, Fooks C, Naylor CD. Ottawa, Canadian Medical Association, 1996, pp 339–345Google Scholar

16. Anderson GM, Kerluke KJ, Pulcins IR, Hertzman C, Barer ML: Trends and determinants of prescription drug expenditures in the elderly: data from the British Columbia Pharmacare Program. Inquiry 1993; 30:199–207Medline, Google Scholar

17. Davidson W, Molloy DW, Somers G, Bedard M: Relation between physician characteristics and prescribing for elderly people in New Brunswick. Can Med Assoc J 1994; 150:917–921Google Scholar

18. Guess HA, Strand LM, Helston D, Lydick EG, Bergman U, Wolski K: Fatal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage or perforation among users and nonusers of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in Saskatchewan, Canada. J Clin Epidemiol 1988; 41:35–45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Rawson NS, Malcolm E: Validity of the Recording of Cholecystectomy and Hysterectomy in the Saskatchewan Health Care Datafiles. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, Pharmacoepidemiology Research Consortium, 1995Google Scholar

20. Thiessen BQ, Wallace SM, Blackburn JL, Wilson TW, Bergman U: Increased prescribing of antidepressants subsequent to beta-blocker therapy. Arch Intern Med 1990; 150:2286–2290Google Scholar

21. Pindyck RS, Rubinfeld DL: Econometric Models and Economic Forecasts, 4th ed. New York, Irwin McGraw-Hill, 1998Google Scholar

22. SAS/ETS Software: Time Series Forecasting, version 6, 1st ed. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1995Google Scholar

23. Dickey DA, Fuller WA: Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. J Am Statistical Assoc 1979:427–431Google Scholar

24. Ljung GM, Box GEP: On a measure of lack of fit in time series models. Biometrika 1978; 65:297–303Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Anthony RN, Young DW: Management Control in Nonprofit Organizations, 5th ed. New York, Irwin McGraw-Hill, 1994Google Scholar

26. Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC: Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:313–321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Parikh SV, Wasylenki D, Goering P, Wong J: Mood disorders: rural/urban differences in prevalence, health care utilization, and disability in Ontario. J Affect Disord 1996; 38:57–65Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Parikh SV, Lesage AD, Kennedy SH, Goering P: Depression in Ontario: under-treatment and factors related to antidepressant use. J Affect Disord 1999; 52:57–76Google Scholar

29. Flint AJ: Pharmacologic treatment of depression in late life. Can Med Assoc J 1997; 157:1061–1067Google Scholar

30. Schneider LS: Pharmacologic considerations in the treatment of late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1996; 4(suppl 1):S51–S65Google Scholar

31. Barbey JT, Roose SP: SSRI safety in overdose. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 15):42–48Google Scholar

32. Schuck PH: Government funding for organ transplants. J Health Polit Policy Law 1989; 14:169–190Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar