Lifting the Veil on Trichotillomania

“Dr. D,” a 32-year-old female general practitioner, presented to a psychiatric referral clinic with a history of repetitive hair pulling since age 14. Recently the hair pulling had escalated, and it now occupied 2–3 hours per day, usually during the evening when Dr. D was relaxing. Despite imaginative efforts to conceal her missing hair and eyebrows, Dr. D felt that she was “fighting a losing battle.” She reported an overpowering urge to touch, select, and pull out particular hairs and described feelings of tension that were only alleviated by the act of hair pulling. This behavior had led to a growing sense of frustration and shame and avoidance of social contact. When asked about her experience with hair pulling in her own medical practice, Dr. D replied that on numerous occasions she had asked patients with unusual scalp patches about deliberate hair pulling and that the patients invariably denied it. What are the diagnostic issues in Dr. D’s case? What are the potential complications and comorbidities to look out for? What do we know about the neurobiology of this disorder? What treatment options are supported by the evidence? What are the key directions for future clinical and neuroscience research?

Scope of the Problem and Diagnostic Considerations

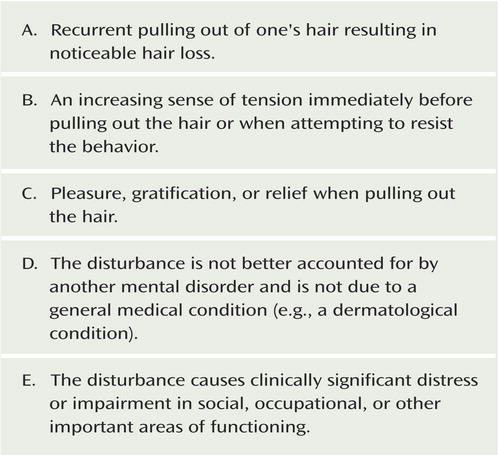

Trichotillomania is a poorly understood disorder characterized by repetitive hair pulling that leads to noticeable hair loss, distress, and social or functional impairment (1 , 2) . The peak age at onset is 12–13 years, and the disorder is often chronic and difficult to treat (3 , 4) . Hair pulling in early childhood (<5 years of age) can be regarded as a distinct clinical entity that tends to be self-limiting without the need for intervention (2 , 5) . Trichotillomania was first described in the literature over 100 years ago by French dermatologist Hallopeau. In DSM-IV, it is categorized as an impulse control disorder; diagnostic criteria are listed in Figure 1 . Although rising tension and subsequent pleasure, gratification, or relief are integral to the current diagnostic criteria for trichotillomania, many people with debilitating hair pulling do not endorse these criteria (6 , 7) .

Trichotillomania is typically confined to one or two sites. It most frequently affects the scalp but can also involve the eyelashes, eyebrows, pubic hair, body hair, and facial hair (8) . Patients tend to be highly secretive about the condition and to regard their behavior as shameful. Many hair pullers also exhibit additional stereotypic movements, such as nail biting, knuckle cracking, touching or playing with pulled hair, and hair eating (trichophagia) (6 , 9) . Along with the cosmetic and psychosocial consequences of the disorder, medical complications can occur, including infection, permanent loss of hair, repetitive stress injury, carpal tunnel syndrome (10) , and gastrointestinal obstruction with bezoars as a result of trichophagia (11) .

Epidemiology and Comorbidity

There have been no populationwide epidemiological studies of trichotillomania. In a survey of 2,500 college students, lifetime prevalence was estimated at 0.6% when strict DSM-III-R criteria were used (12) . When the criteria were relaxed to exclude the items on sense of tension before hair pulling and gratification or relief afterward, pathological hair pulling was evident in 1.5% of males and 3.4% of females in the sample. In adult recruitment studies, female participants have typically outnumbered males by at least 3 to 1.

Trichotillomania is frequently linked with other conditions, notably mood and anxiety disorders. In a study of 60 adult hair pullers recruited from a trichotillomania clinic and newspaper advertisements (6) , 82% had a past or current axis I diagnosis other than trichotillomania according to semistructured clinical interview. The highest reported lifetime prevalence estimates of comorbid disorders, occurring in >10% of the sample, were major depression, anxiety disorders (mainly generalized anxiety disorder and simple phobias), and substance use disorders; 23% of the sample met criteria for current major depression, and 10% for current obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). In a study of 15 younger patients with hair pulling (mean age=12 years) recruited from an outpatient clinic, nine met criteria for additional diagnoses, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), tic disorder, OCD, and major depression (13) .

Etiology

Hair pulling and related grooming phenomena frequently occur in family members of trichotillomania patients, and it is probable that multiple genes confer biological vulnerability (8) . Zuchner and colleagues identified mutations in the Slit and Trk-like 1 (SLITRK1) gene in two trichotillomania subjects that were absent in more than 2,000 comparison subjects (14) . This gene is associated with cortex development and neuronal growth, and rare mutations have also been associated with Tourette’s syndrome (15) . Hemmings et al. (16) reported evidence for differences in distributions of serotonin 2A receptor genes between trichotillomania patients and comparison subjects. In animal work, Greer and Capecchi (17) reported that mice with mutation of the hoxb8 neurodevelopmental gene showed aberrant grooming behavior including hair pulling. Although preliminary, these data implicate polymorphisms in genes controlling brain development and neuromodulation in trichotillomania.

In some cases of trichotillomania, there is an apparent etiological role for stress; hair pulling can be seen as a soothing behavior that is driven by rising tension. Trichotillomania also shows unexpectedly high overlap with posttraumatic stress disorder (18) , raising the possibility of additional affective contributions. Another school of thought emphasizes hair pulling as addictive or positively reinforcing insofar as it is associated with rising tension beforehand and relief afterward (19) . However, for many patients, hair pulling is undertaken during times of relaxation and may in fact serve a self-stimulatory function (19) . From a neurocognitive perspective, trichotillomania can be considered a habit disorder in which the sufferer is unable to exert sufficient top-down inhibitory control (20) . Central to this model is the notion that the basal ganglia play a role in habit formation and that the frontal lobes are critical for normally suppressing or inhibiting such habits (20 – 22) .

Trichotillomania and the Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum

It has been proposed that certain conditions fall within an obsessive-compulsive spectrum, sharing overlapping clinical features, genetic contributions, and possibly treatment response (23 , 24) . Proposed members of this spectrum include OCD, trichotillomania, severe nail biting, compulsive skin picking, tic disorders, and eating disorders. Phenomenologically, trichotillomania is akin to OCD and many of these other conditions in that it is associated with irresistible urges to perform unwanted repetitive behavior (20) . In a study by Richter and colleagues (25) , OCD patients were found to have a greater lifetime occurrence of multiple spectrum conditions compared with panic disorder and social phobia patients. Higher than expected rates of trichotillomania, nail biting, and skin picking have also been found in relatives of OCD patients (26) .

Several differences between trichotillomania and OCD have been noted, however (2 , 5) . Hair pulling is not usually driven by recurrent intrusive thoughts, whereas in OCD compulsions are frequently undertaken in response to obsessions. In comparison with OCD, trichotillomania has a younger peak age at onset, affects a greater proportion of females than males, and has lower rates of comorbidity (6 , 8 , 27) . There may also be differences between trichotillomania and OCD in terms of neural dysfunction and cognitive profiles (discussed below).

Neuroimaging Dysfunction

Although caudate abnormalities have been observed in OCD, Stein et al. (28) found no evidence to support the existence of volumetric caudate abnormalities in subjects with trichotillomania. O’Sullivan et al. (29) found reduced left putamen volumes (part of the fronto-striatal motor circuit) in trichotillomania patients (medication status was not specified). Later, Stein et al. (30) , using single photon emission computed tomography, found reduced neural activity in the left putamen and several frontal regions after 12 weeks of citalopram treatment in trichotillomania patients.

There is also evidence for involvement of the cerebellum in trichotillomania. A resting-state positron emission tomography study conducted by Swedo et al. (31) identified disproportionately increased brain metabolism in medication-free patients with trichotillomania in the cerebellum bilaterally and in the right superior parietal cortex. The relationship between these abnormalities and trichotillomania symptoms was difficult to evaluate, as metabolic rates correlated positively with trait (chronic) measures of anxiety but negatively with trichotillomania symptom severity. Evidence for cerebellar involvement has also been obtained in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies. Keuthen and colleagues reported reduced volumes in this region in medication-free trichotillomania patients (32) .

It is interesting to contrast these preliminary findings for trichotillomania, implicating regions such as the putamen and cerebellum, with findings in OCD, for which abnormalities have been reported in the orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortices and the caudate nucleus (20) . Collectively, these findings suggest some difference in the neural underpinnings of the two disorders, and this issue must be addressed in direct neuroimaging comparisons.

Structural MRI studies undertaken so far have used region-of-interest methods, which require that researchers select specific regions for volumetric analysis a priori. This approach is questionable given the paucity of data about the neurobiology of trichotillomania. Whole-brain analysis using techniques such as voxel-based morphometry may be useful in this regard. This unbiased automated approach allows for investigation of the whole brain for gray and white matter changes while taking into account multiple comparisons without the need for an a priori structural hypothesis. Functional neuroimaging studies using symptom provocation and exposure to symptom-relevant stimuli have been useful in OCD research (33) and could be applied to the study of trichotillomania.

Neurocognitive Dysfunction

Neuropsychological assessment is another useful tool for investigating neural dysfunction in trichotillomania and the disorder’s relationship with other obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. The problem of comorbidity confounds many cognitive studies of trichotillomania because a number of disorders, including depression, are themselves linked with cognitive dysfunction. Only a few studies have attempted to focus on “pure” cases of trichotillomania using hypothesis-driven tests. Recently, computerized assessment was used to compare cognition between patients with trichotillomania and no comorbid disorders, patients with OCD and no comorbid disorders, and healthy volunteers (34 , 35) . Both patient groups showed impaired impulse control, as measured with a stop-signal task. In the trichotillomania group, the impulse control deficit was especially severe and was correlated with symptom severity. Patients with OCD also showed cognitive inflexibility and executive dysfunction across several other neurocognitive tests, whereas trichotillomania patients did not, which suggests more restricted involvement of cortico-subcortical neural circuitry in trichotillomania. Stop-signal performance is dependent on the right inferior frontal gyrus (36 , 37) . In this light, the right inferior frontal gyrus and connected regions should be further investigated in neuroimaging studies of trichotillomania. The finding of markedly impaired response inhibition in trichotillomania (35) is reminiscent of findings in ADHD (38) and points toward a possible role for cognition-enhancing agents (39 , 40 , 41) .

Treatment

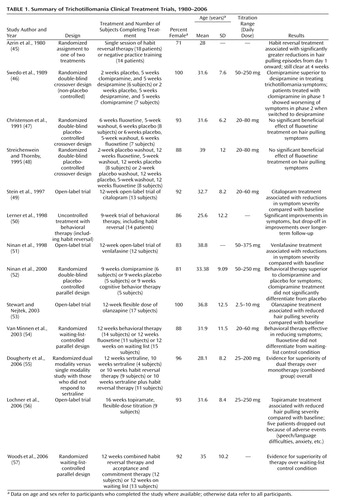

Methods for assessing trichotillomania have varied widely among studies (7) , and few objective validated clinical instruments have been developed. Examples include the Psychiatric Institute Trichotillomania Scale (42) and the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Hair pulling Scale, which was derived from the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale and has good psychometric properties (43 , 44) .

Table 1 summarizes the published literature on treatment trials for trichotillomania. These studies have investigated a range of behavioral therapies and pharmacotherapies. Habit reversal, a behavioral therapy that has a long-standing tradition in the treatment of “nervous” habits and tics (58) , involves training participants to undertake alternative, competing, harmless motor responses, such as fist clenching. In early work, Azrin and colleagues (45) conducted a nonblind trial with 34 trichotillomania patients (including four children) randomly assigned to either one session of habit reversal training or a time-matched session of individual negative practice—a technique involving grooming hair without pulling it out (two patients were not evaluated). Habit reversal was superior to negative practice training according to progress reports (rather than validated instruments) as early as day 1, and this difference remained significant at 4 weeks. Lerner and colleagues (50) conducted an uncontrolled evaluation of 9 weeks of behavioral therapy, including habit reversal, for trichotillomania patients. Treatment response was assessed with the Trichotillomania Impairment Scale and the Trichotillomania Severity Score. At immediate follow-up, significant improvements were noted in the patients who completed therapy, although these benefits were diminished at long-term follow-up.

A variety of drug treatments have also been investigated, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) that are known to be effective for OCD (59) . In a 5-week randomized double-blind crossover study, Swedo and colleagues (46) found that clomipramine was superior to the tricyclic desipramine in reducing trichotillomania symptoms in patients who completed treatment, as assessed with the Trichotillomania Impairment Scale, the Trichotillomania Severity Score, and physicians’ ratings of clinical progress. The superiority of the SSRIs mirrors results seen in OCD, for which these agents are effective and non-SSRIs are not (see reference 59 for a review). Ninan and colleagues (52) subsequently compared the effects of 9 weeks of clomipramine treatment, placebo, and cognitive behavior therapy (including habit reversal) in a parallel randomized study. The drug and placebo conditions were double-blind, although there was no suitable control for the therapy condition. Behavioral therapy was superior to clomipramine and placebo in reducing trichotillomania symptoms as assessed by the Trichotillomania Impairment Scale and the Trichotillomania Severity Score. Patients in the clomipramine group experienced greater improvement than those in the placebo group, but this finding failed to reach statistical significance.

Three randomized controlled studies have evaluated fluoxetine. Christenson and colleagues (47) conducted a 6-week double-blind placebo-controlled study, and Streichenwein and Thornby (48) used a similar design but with a 12-week treatment period. In both studies, assessments included hair pulling diaries and counting pulled hairs. Neither study found evidence for superiority of fluoxetine over placebo. Van Minnen et al. (54) compared fluoxetine and behavioral therapy in a 12-week parallel-groups waiting-list-control design (without placebo control) using the MGH Hair pulling Scale to assess symptoms. Behavioral therapy, including stimulus control and stimulus response management techniques, was superior to the fluoxetine and waiting-list conditions, and the fluoxetine condition did not differentiate from the waiting-list condition. Woods and colleagues (57) found that 12 weeks of behavioral therapy (including habit reversal) was superior to the waiting-list-control condition in reducing scores on the MGH Hair pulling Scale and the Trichotillomania Impairment Scale.

Dual treatment with behavioral therapy and an SSRI may provide advantages over monotherapy in some cases. Dougherty and colleagues (55) examined the effects of adding habit reversal therapy for trichotillomania patients who had not responded to 12 weeks of sertraline treatment. At the end of the 22-week study, participants who received the dual treatment had superior outcomes according to scores on the MGH Hair pulling Scale and Clinical Global Impression scale compared with the monotherapy group. Other open-label trials have found significant symptom improvement with other drugs, including citalopram (an SSRI), venlafaxine (a mixed reuptake inhibitor), topiramate (an antiepileptic with complex actions), and olanzapine (a dopamine and serotonin receptor antagonist) (49 , 51 , 53 , 56) (see Table 1 ).

So far, few if any treatment trials have been sufficiently rigorous to provide strong evidence. Further substantiation of existing and novel therapies and combined treatment strategies using properly constituted randomized, controlled trials is required.

Summary and Recommendations

Trichotillomania is an underdiagnosed and underreported condition associated with significant social and functional impairment (8) . The etiology and brain basis of trichotillomania remain unclear, which hampers improvements in diagnostic classification and treatment for this and related obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Application of techniques from the neurosciences, including neurochemical challenge, structural and functional neuroimaging, and genetic analysis, will improve our understanding of these issues. Studies of unaffected relatives will help to elucidate the state versus trait nature of any abnormalities that are identified.

Patients actively disguise their symptoms to avoid disclosure; clinicians should be vigilant when patients present with inappropriate or unusual head coverings. Assessment requires great clinical sensitivity, as hair pulling can also affect other sites on body (including the pubic region), and patients frequently regard their behavior as shameful. A classic faux pas is to rush in and ask to examine the affected sites without first taking care to establish rapport and trust. Clinicians should bear in mind that trichotillomania frequently presents with concurrent depression and anxiety disorders. Moreover, given the link between trichotillomania and other obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders, careful screening is necessary to ensure accurate diagnosis.

How should a patient such as Dr. D be managed? Given the limited available clinical research evidence, no formal treatment algorithm for trichotillomania can be formulated, and it is important to make patients aware of this; the patient’s choice is likely to be paramount in treatment selection. Clinical effectiveness usually depends on a balance between efficacy and tolerability. For pharmacotherapy, clomipramine (starting at 50 mg/day and titrating up to 250 mg/day as tolerated) could be considered in light of evidence from a randomized trial (46) . An SSRI, such as citalopram (starting at 20 mg/day and titrating up to 60 mg/day as tolerated), may be preferable given the superior safety and tolerability of this drug class for related conditions, such as OCD, and the positive results reported for an open-label study with trichotillomania patients (49) . A course of behavioral therapy incorporating habit reversal should also be considered (54) . Treatment response may be monitored with the Psychiatric Institute Trichotillomania Scale or the MGH Hair pulling Scale, along with direct observation of the affected sites. It may be that dual treatment, using pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, is more effective than monotherapy, at least in patients who do not respond to an SSRI in the first instance (55) . We would also recommend educational material (60) and support web sites (e.g., www.trich.org) for the patient, as these can be of therapeutic value (61) .

1. Soriano JL, O’Sullivan RL, Baer L, Phillips KA, McNally RJ, Jenike MA: Trichotillomania and self-esteem: a survey of 62 female hair pullers. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57:77–82Google Scholar

2. Keuthen NJ, O’Sullivan RL, Sprich-Buckminster S: Trichotillomania: current issues in conceptualization and treatment. Psychother Psychosom 1998; 67:202–213Google Scholar

3. Diefenbach GJ, Reitman D, Williamson DA: Trichotillomania: a challenge to research and practice. Clin Psychol Rev 2000; 20:289–309Google Scholar

4. Walsh KH, McDougle CJ: Trichotillomania: presentation, etiology, diagnosis, and therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol 2001; 2:327–333Google Scholar

5. Swedo SE, Leonard HL: Trichotillomania: an obsessive compulsive spectrum disorder? Psychiatr Clin North Am 1992; 15:777–790Google Scholar

6. Christenson GA, Mackenzie TB, Mitchell JE: Characteristics of 60 adult chronic hair pullers. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:365–370Google Scholar

7. Rothbaum BO, Ninan PT: The assessment of trichotillomania. Behav Res Ther 1994; 32:651–662Google Scholar

8. Cohen LJ, Stein DJ, Simeon D, Spadaccini E, Rosen J, Aronowitz B, Hollander E: Clinical profile, comorbidity, and treatment history in 123 hair pullers: a survey study. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:319–326Google Scholar

9. Du Toit PL, van Kradenburg J, Niehaus DJ, Stein DJ: Characteristics and phenomenology of hair-pulling: an exploration of subtypes. Compr Psychiatry 2001; 42:247–256Google Scholar

10. Frey AS, McKee M, King RA, Martin A: Hair apparent: Rapunzel syndrome (clin case conf). Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:242–248Google Scholar

11. Bouwer C, Stein DJ: Trichobezoars in trichotillomania: case report and literature overview. Psychosom Med 1998; 60:658–660Google Scholar

12. Christenson GA, Pyle RL, Mitchell JE: Estimated lifetime prevalence of trichotillomania in college students. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52:415–417Google Scholar

13. King RA, Scahill L, Vitulano LA, Schwab-Stone M, Tercyak KP Jr, Riddle MA: Childhood trichotillomania: clinical phenomenology, comorbidity, and family genetics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:1451–1459Google Scholar

14. Zuchner S, Cuccaro ML, Tran-Viet KN, Cope H, Krishnan RR, Pericak-Vance MA, Wright HH, Ashley-Koch A: SLITRK1 mutations in trichotillomania. Mol Psychiatry 2006; 11:887–889Google Scholar

15. Abelson JF, Kwan KY, O’Roak BJ, Baek DY, Stillman AA, Morgan TM, Mathews CA, Pauls DL, Rasin MR, Gunel M, Davis NR, Ercan-Sencicek AG, Guez DH, Spertus JA, Leckman JF, Dure LS 4th, Kurlan R, Singer HS, Gilbert DL, Farhi A, Louvi A, Lifton RP, Sestan N, State MW: Sequence variants in SLITRK1 are associated with Tourette’s syndrome. Science 2005; 310:317–320Google Scholar

16. Hemmings SM, Kinnear CJ, Lochner C, Seedat S, Corfield VA, Moolman-Smook JC, Stein DJ: Genetic correlates in trichotillomania: a case-control association study in the South African Caucasian population. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 2006; 43:93–101Google Scholar

17. Greer JM, Capecchi MR: Hoxb8 is required for normal grooming behavior in mice. Neuron 2002; 33:23–34Google Scholar

18. Gershuny BS, Keuthen NJ, Gentes EL, Russo AR, Emmott EC, Jameson M, Dougherty DD, Loh R, Jenike MA: Current posttraumatic stress disorder and history of trauma in trichotillomania. J Clin Psychol 2006; 62:1521–1529Google Scholar

19. Stein DJ, Chamberlain SR, Fineberg N: An A-B-C model of habit disorders: hair-pulling, skin-picking, and other stereotypic conditions. CNS Spectr 2006; 11:824–827Google Scholar

20. Chamberlain SR, Blackwell AD, Fineberg NA, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ: The neuropsychology of obsessive compulsive disorder: the importance of failures in cognitive and behavioural inhibition as candidate endophenotypic markers. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2005; 29:399–419Google Scholar

21. Graybiel AM: The basal ganglia and cognitive pattern generators. Schizophr Bull 1997; 23:459–469Google Scholar

22. Chamberlain SR, Fineberg NA, Menzies LA, Blackwell AD, Bullmore ET, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ: Impaired cognitive flexibility and motor inhibition in unaffected first-degree relatives of patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:335–338Google Scholar

23. Stein DJ, Hollander E: Obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:265–266Google Scholar

24. Hollander E, Allen A: Is compulsive buying a real disorder, and is it really compulsive? (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1670–1672Google Scholar

25. Richter MA, Summerfeldt LJ, Antony MM, Swinson RP: Obsessive-compulsive spectrum conditions in obsessive-compulsive disorder and other anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety 2003; 18:118–127Google Scholar

26. Bienvenu OJ, Samuels JF, Riddle MA, Hoehn-Saric R, Liang KY, Cullen BA, Grados MA, Nestadt G: The relationship of obsessive-compulsive disorder to possible spectrum disorders: results from a family study. Biol Psychiatry 2000; 48:287–293Google Scholar

27. Lochner C, Seedat S, du Toit PL, Nel DG, Niehaus DJ, Sandler R, Stein DJ: Obsessive-compulsive disorder and trichotillomania: a phenomenological comparison. BMC Psychiatry 2005; 5:2Google Scholar

28. Stein DJ, Coetzer R, Lee M, Davids B, Bouwer C: Magnetic resonance brain imaging in women with obsessive-compulsive disorder and trichotillomania. Psychiatry Res 1997; 74:177–182Google Scholar

29. O’Sullivan RL, Rauch SL, Breiter HC, Grachev ID, Baer L, Kennedy DN, Keuthen NJ, Savage CR, Manzo PA, Caviness VS, Jenike MA: Reduced basal ganglia volumes in trichotillomania measured via morphometric magnetic resonance imaging. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 42:39–45Google Scholar

30. Stein DJ, van Heerden B, Hugo C, van Kradenburg J, Warwick J, Zungu-Dirwayi N, Seedat S: Functional brain imaging and pharmacotherapy in trichotillomania: single photon emission computed tomography before and after treatment with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2002; 26:885–890Google Scholar

31. Swedo SE, Rapoport JL, Leonard HL, Schapiro MB, Rapoport SI, Grady CL: Regional cerebral glucose metabolism of women with trichotillomania. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:828–833Google Scholar

32. Keuthen NJ, Makris N, Schlerf JE, Martis B, Savage CR, McMullin K, Seidman LJ, Schmahmann JD, Kennedy DN, Hodge SM, Rauch SL: Evidence for reduced cerebellar volumes in trichotillomania. Biol Psychiatry (epub ahead of print, Aug 29, 2006)Google Scholar

33. Saxena S, Rauch SL: Functional neuroimaging and the neuroanatomy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2000; 23:563–586Google Scholar

34. Chamberlain SR, Blackwell AD, Fineberg NA, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ: Strategy implementation in obsessive-compulsive disorder and trichotillomania. Psychol Med 2006; 36:91–97Google Scholar

35. Chamberlain SR, Fineberg NA, Blackwell AD, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ: Motor inhibition and cognitive flexibility in obsessive-compulsive disorder and trichotillomania. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1282–1284Google Scholar

36. Aron AR, Robbins TW, Poldrack RA: Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci 2004; 8:170–177Google Scholar

37. Aron AR, Fletcher PC, Bullmore ET, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW: Stop-signal inhibition disrupted by damage to right inferior frontal gyrus in humans. Nat Neurosci 2003; 6:115–116Google Scholar

38. Aron AR, Poldrack RA: The cognitive neuroscience of response inhibition: relevance for genetic research in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 57:1285–1292Google Scholar

39. Turner DC, Robbins TW, Clark L, Aron AR, Dowson J, Sahakian BJ: Cognitive enhancing effects of modafinil in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003; 165:260–269Google Scholar

40. Chamberlain SR, Muller U, Blackwell AD, Clark L, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ: Neurochemical modulation of response inhibition and probabilistic learning in humans. Science 2006; 311:861–863Google Scholar

41. Turner DC, Clark L, Dowson J, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ: Modafinil improves cognition and response inhibition in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2004; 55:1031–1040Google Scholar

42. Winchel RM, Jones JS, Molcho A, Parsons B, Stanley B, Stanley M: The Psychiatric Institute Trichotillomania Scale (PITS). Psychopharmacol Bull 1992; 28:463–476Google Scholar

43. Keuthen NJ, O’Sullivan RL, Ricciardi JN, Shera D, Savage CR, Borgmann AS, Jenike MA, Baer L: The Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Hairpulling Scale, 1: development and factor analyses. Psychother Psychosom 1995; 64:141–145Google Scholar

44. O’Sullivan RL, Keuthen NJ, Hayday CF, Ricciardi JN, Buttolph ML, Jenike MA, Baer L: The Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Hairpulling Scale, 2: reliability and validity. Psychother Psychosom 1995; 64:146–148Google Scholar

45. Azrin NH, Nunn RG, Frantz SE: Treatment of hairpulling (trichotillomania): a comparative study of habit reversal and negative practice training. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 1980; 11:13–20Google Scholar

46. Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Rapoport JL, Lenane MC, Goldberger EL, Cheslow DL: A double-blind comparison of clomipramine and desipramine in the treatment of trichotillomania (hair pulling). N Engl J Med 1989; 321:497–501Google Scholar

47. Christenson GA, Mackenzie TB, Mitchell JE, Callies AL: A placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover study of fluoxetine in trichotillomania. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1566–1571Google Scholar

48. Streichenwein SM, Thornby JI: A long-term, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial of the efficacy of fluoxetine for trichotillomania. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1192–1196Google Scholar

49. Stein DJ, Bouwer C, Maud CM: Use of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram in treatment of trichotillomania. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1997; 247:234–236Google Scholar

50. Lerner J, Franklin ME, Meadows EA, Hembree E, Foa EB: Effectiveness of a cognitive behavioral treatment program for trichotillomania: an uncontrolled evaluation. Behav Ther 1998; 29:157–171Google Scholar

51. Ninan PT, Knight B, Kirk L, Rothbaum BO, Kelsey J, Nemeroff CB: A controlled trial of venlafaxine in trichotillomania: interim phase I results. Psychopharmacol Bull 1998; 34:221–224Google Scholar

52. Ninan PT, Rothbaum BO, Marsteller FA, Knight BT, Eccard MB: A placebo-controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy and clomipramine in trichotillomania. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61:47–50Google Scholar

53. Stewart RS, Nejtek VA: An open-label, flexible-dose study of olanzapine in the treatment of trichotillomania. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:49–52Google Scholar

54. Van Minnen A, Hoogduin KA, Keijsers GP, Hellenbrand I, Hendriks GJ: Treatment of trichotillomania with behavioral therapy or fluoxetine: a randomized, waiting-list controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:517–522Google Scholar

55. Dougherty DD, Loh R, Jenike MA, Keuthen NJ: Single modality versus dual modality treatment for trichotillomania: sertraline, behavioral therapy, or both? J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:1086–1092Google Scholar

56. Lochner C, Seedat S, Niehaus DJ, Stein DJ: Topiramate in the treatment of trichotillomania: an open-label pilot study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2006; 21:255–259Google Scholar

57. Woods DW, Wetterneck CT, Flessner CA: A controlled evaluation of acceptance and commitment therapy plus habit reversal for trichotillomania. Behav Res Ther 2006; 44:639–656Google Scholar

58. Azrin NH, Nunn RG: Habit-reversal: a method of eliminating nervous habits and tics. Behav Res Ther 1973; 11:619–628Google Scholar

59. Fineberg NA, Gale TM: Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2005; 8:107–129Google Scholar

60. Penzel F: The Hair-Pulling Problem: A Complete Guide to Trichotillomania. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 2003Google Scholar

61. Boughn S, Holdom JA: Trichotillomania: women’s reports of treatment efficacy. Res Nurs Health 2002; 25:135–144Google Scholar