Social Phobia Subtypes in the National Comorbidity Survey

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This article presents epidemiologic data on the distinction between social phobia characterized by pure speaking fears and that characterized by other social fears. METHOD: The data come from the National Comorbidity Survey (N=8,098). Social phobia was assessed with a revised version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. RESULTS: Latent class analysis showed that the brief set of social fears assessed in the survey can be disaggregated into a class characterized largely by speaking fears and a second class characterized by a broader range of social fears. One-third of the people with lifetime social phobia exclusively reported speaking fears, while the other two-thirds also had at least one of the other social fears assessed. The vast majority of the latter had multiple social fears including, in most cases, both performance and interactional fears. The two subtypes were similar in age at onset distribution, family history, and certain sociodemographic correlates. However, the social phobia characterized by pure speaking fears was less persistent, less impairing, and less highly comorbid with other DSM-III-R disorders than was social phobia characterized by other social fears. CONCLUSIONS: Further general population research assessing more performance and interaction fears is needed to determine whether social phobia subtypes can be refined and whether the subtypes are better conceptualized as distinct disorders. In the meantime, people who have social phobia with multiple fears, some of which are nonspeaking fears, appear to have the most impairment and should be the main focus of prevention and intervention efforts.

Social phobia is a commonly occurring anxiety disorder (1–5) often associated with serious role impairment (3, 4, 6, 7). Distinct symptom profiles have been found in clinical samples of some patients suffering exclusively from performance fears (e.g., speaking in public) and others with a broader array of fears that include both performance and interactional fears (e.g., meeting new people) (8–10). The latter disorder is referred to as generalized social phobia (DSM-IV).

Generalized social phobia has been observed to be more severe and disabling than other social phobias (11). Therefore, in planning public health responses to the findings that social phobia affects more than one out of eight people in the population on a lifetime basis (3) and as many as 8% in a year (1, 2), it would be useful to know the proportion who have broad-based and seriously impairing social fears versus less extensive or impairing fears. This was the purpose of the present investigation. In this report we show that two empirically derived subtypes of social phobia can be found in a large general population survey that distinguish people with exclusively speaking fears from other people with social phobia. While it has previously been noted that many persons in the community suffer from public speaking fears that can be considered a form of social phobia (12), to our knowledge no previous epidemiologic study has examined this or other social phobia subtypes in the general population. We present data that compare these subtypes on family history, comorbidity, impairment, and sociodemographic correlates.

METHOD

Sample

The data come from the National Comorbidity Survey (1), a survey of 8,098 respondents in the age range 15–54 years who were selected from the noninstitutionalized household population of the coterminous United States; the sample included an equal-probability subsample of students in campus group housing. The survey was fielded between September 1990 and March 1992. Interviews were administered face-to-face in the homes of the respondents and averaged somewhat more than 2 hours to complete. The response rate was 82.4%. The data were weighted for differential probabilities of selection and differential nonresponse. More details on the design of the National Comorbidity Survey have been reported elsewhere (1, 13).

Diagnostic Assessment

The survey diagnoses were based on a modified version of the World Health Organization's Composite International Diagnostic Interview (14), a structured interview designed to be administered by trained interviewers who are not clinicians. The diagnoses included in the full National Comorbidity Survey were DSM-III-R anxiety disorders (social phobia, agoraphobia, simple phobia, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder), mood disorders (major depression, dysthymia, mania), addictive disorders (alcohol and drug abuse and dependence), and antisocial personality disorder. The WHO field trials of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (15) and the National Comorbidity Survey clinical reappraisal study (16–20) both indicated good reliability and acceptable validity of these diagnoses.

Social phobia was assessed by asking the respondents whether there was ever a time when any of six situations always made them so afraid that they either tried to avoid it or felt very uncomfortable in the situation. The situations were speaking in public, having to use the toilet when away from home, eating or drinking in public, talking to people when you might have nothing to say or might sound foolish, writing while someone watches, and talking in front of a small group of people (“small” was not defined). The main change to the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview made in the National Comorbidity Survey was that respondents were asked to review this list visually as the interviewer read the items, in an effort to control the pace of review, to focus memory search, and to reduce the chance of inducing the “no” response set that has been documented as occurring when yes-or-no questions are presented in lists of this sort (21). Respondents who endorsed one or more of these situational descriptors were asked the remaining social phobia questions from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. The National Comorbidity Survey clinical reappraisal study (20) showed acceptable agreement (kappa=0.68 with a standard error of 0.09) between DSM-III-R diagnoses based on these structured questions and diagnoses based on blind clinical reinterviews using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (22).

Other Measures

The sociodemographic variables evaluated for association with social phobia subtypes were age, sex, region, urbanicity, education, income, and marital status. Subtype differences in parent histories of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and substance dependence were examined by using the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria (FH-RDC) interview (23). As the latter does not include generalized anxiety disorder, questions developed by Kendler et al. (24) to assess generalized anxiety disorder in a format comparable to that of the FH-RDC interview were used. The diagnoses made with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview were used to study the comorbidity of the social phobia subtypes with other DSM-III-R disorders. Finally, impairments were evaluated on the basis of self-reports of whether the respondent's phobia had ever interfered a lot with his or her life or activities, whether the respondent had ever sought treatment for the phobia, and whether he or she had ever taken medications for the phobia.

Analysis Procedures

Latent class analysis (25) was used to determine how many subtypes underlie the observed covariances among the six fears of social situations assessed in the National Comorbidity Survey. Latent class analysis is a categorical equivalent of factor analysis that postulates the existence of a discrete latent variable (as opposed to one or more continuous variables in factor analysis) defining classes that explain the covariances among observed variables (26). The Kaplan-Meier method (27) was used to calculate curves for age at onset and for time to “offset,” the number of years between retrospectively reported age at onset and age at the time of the most recent phobic symptoms. Between-subtype differences in family history, comorbidity, and impairment were assessed with logistic regression models (28). These models began by comparing the subtypes with pure speaking fears and with nonspeaking fears and then evaluated differences within each by distinguishing cases with public speaking fears exclusively from others in the pure speaking subtype and cases based on number of social fears (one, two, or three or more) in the subtype with nonspeaking fears. Sociodemographic correlates were also studied by using logistic regression models.

The clustering and weighting of the National Comorbidity Survey makes it inappropriate to use conventional significance tests to evaluate parameter estimates because the latter underestimate the magnitude of standard errors. Therefore, the Taylor series linearization method (29) was used to adjust standard errors of means, and the method of jackknife repeated replications (30) was used to adjust the 95% confidence intervals of the odds ratios. Global significance tests comparing the five subsamples defined by the cross-classification of subtype and number of social fears were done by using Wald chi-square tests calculated on variance-covariance matrices, adjusted by the method of jackknife repeated replications, among the logistic regression coefficients.

RESULTS

Lifetime Prevalences of Social Fears and Social Phobia

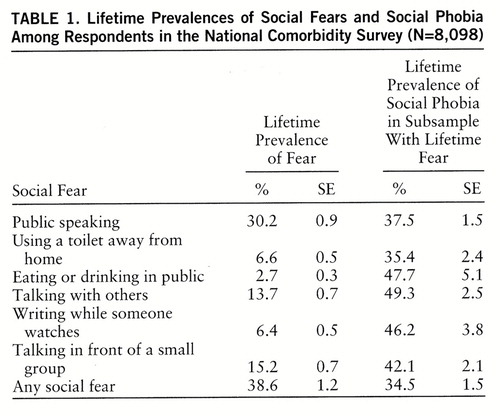

As shown in table 1, the lifetime prevalences of the six social fears in the total sample ranged from 2.7% for fear of eating or drinking in public to 30.2% for fear of speaking in public. The lifetime prevalence of at least one fear was 38.6%. The speaking fears were the most common. The conditional probabilities of social phobia given a particular social fear (i.e., the proportion of people with a given fear who met the criteria for social phobia) had a much narrower range, from 35.4% for fear of using a toilet away from home to 49.3% for fear of talking with others, and they averaged 34.5% across all fears.

Latent Class Analysis of Lifetime Social Fears

Latent class analysis models for the six lifetime social fears were fit for between one and four classes. A three-class model was found to provide the best fit, as indicated by the improvement over a two-class model (χ2=314.2, df=7, p<0.001) and the failure of a four-class model to improve over the three-class model (χ2=0.01, df=7, p=1.00). Class 1 was characterized by low endorsement probabilities. Class 2 was characterized by a 93% probability of fear of speaking in public, a probability over 50% of fear of speaking in front of a small group, and a 32% probability of fear of talking with others. Class 3 was characterized by comparatively high probabilities of all six fears.

Lifetime and 12-Month Prevalences of Social Fear and Phobia Subtypes

On the basis of the results of the latent class analysis, the respondents with social fears were divided into two broad groups, those with pure speaking fears and those who endorsed at least one other social fear (with or without a speaking fear). Because of the much higher prevalence of public speaking fear than other social fears, the group with pure speaking fear was further divided into those with public speaking fear only and those with more extensive speaking fears. The group that endorsed other social fears, in comparison, was further divided into those with one, two, and three or more social fears in order to distinguish the effect of number from the effect of type of social fears.

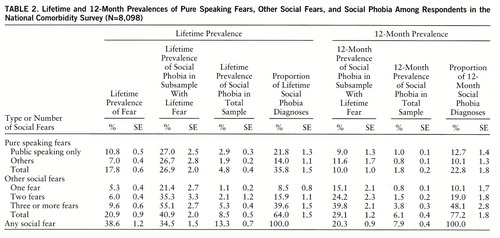

The lifetime and 12-month prevalences of social fears and social phobia in these various subgroups are reported in table 2. Similar proportions of the total sample reported one or more lifetime pure speaking fears (17.8%) and other social fears (20.9%). Within the subsample with pure speaking fears, over one-half reported that their only social fear was public speaking. Within the group with other social fears, about one-fourth reported only one of the fears, while close to one-half reported three or more of the six social fears.

As shown in the third data column, a significantly lower proportion of those with pure speaking fears (26.9% of 1,441) than other social fears (40.9% of 1,691) (z=4.9, p<0.001) met the criteria for lifetime social phobia. As a result, even though the lifetime prevalences of pure speaking fears and other social fears were roughly equal, in the total sample the lifetime prevalence of social phobia with nonspeaking fears (8.5%) was much higher than the lifetime prevalence of social phobia with pure speaking fears (4.8%) (z=5.8, p<0.001). There was an even larger difference between the conditional prevalences of 12-month social phobia in the subsamples of people with lifetime pure speaking fears (10.0% of 388) and those with other lifetime social fears (29.1% of 692) (z=12.3, p<0.001), suggesting that the former are less persistent than the latter. There was a significant association between the number of lifetime fears and the probability of lifetime phobia within the subsample having nonspeaking fears, from a low of 21.4% among the 429 respondents with only one fear to a high of 55.1% among the 777 with three or more fears (z=8.8, p<0.001). There was no significant difference, however, between the probability of lifetime social phobia in the subsample of respondents with pure fear of public speaking (27.0% of 875) and the probability for those with other pure speaking fears (26.7% of 567) (z=0.08, p=0.99).

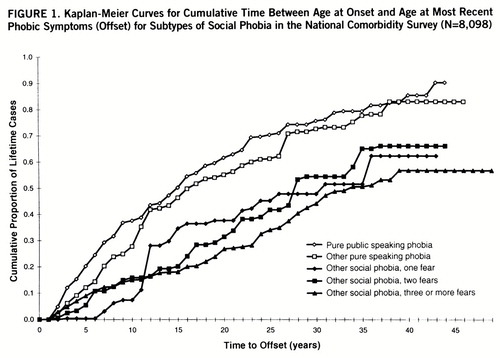

Age at Onset and Time to Offset

Kaplan-Meier cumulative curves for age at onset based on retrospective reports were computed separately for social phobia with pure speaking fears and for subgroups of other social phobias defined on the basis of number and type of fears. No evidence was found for meaningful differences in the age-at-onset distributions of these subsamples.

Kaplan-Meier curves for time to offset were also computed for the same subsamples. Time to offset was the number of years between retrospectively reported age at onset and age at most recent phobic symptoms. As shown in figure 1, time to offset was significantly shorter for social phobia with pure speaking fears than for social phobia with other social fears (χ2=86.2, df=1, p<0.001). There was no significant difference in time to offset, in comparison, among the subsamples defined by number of fears for either the respondents with social phobia and pure speaking fears (χ2=3.0, df=2, p=0.08) or those with social phobia with other social fears (χ2=3.0, df=2, p=0.22).

Parental History of Psychopathology

There were consistently positive associations between parental history of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, substance dependence, and antisocial personality disorder and the respondents' lifetime social phobia. However, we found a statistically significant difference between social phobia with pure speaking fears and other social phobia in only one of the measures of parental psychopathology, maternal generalized anxiety disorder (χ2=8.2, df=2, p<0.001); the prevalence was lower among those with pure speaking fears than among those with other social phobias.

Comorbidity

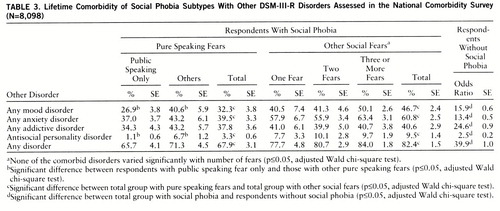

A previous report from the National Comorbidity Survey documented substantial comorbidity of lifetime social phobia and other lifetime DSM-III-R disorders assessed in the survey (3). The results in table 3 show that there was also considerable variation in comorbidity across subtypes of social phobia. Histories of mood disorder, anxiety disorder, and antisocial personality disorder were all significantly more common among respondents who had social phobia with at least one nonspeaking fear than among those with social phobia and pure speaking fears. Among the respondents with social phobia and comorbid disorders, furthermore, those with pure speaking fears were significantly more likely than those with other social fears to report that social phobia was their earliest lifetime disorder (73.4% of 263 versus 59.4% of 570) (z=2.3, p=0.03). For the respondents with social phobia, there was less comorbidity with mood disorder and antisocial personality disorder among those with public speaking fears only than among those with other pure speaking fears. However, comorbidity was not associated with the number of social fears among those with social fears beyond speaking.

Impairment

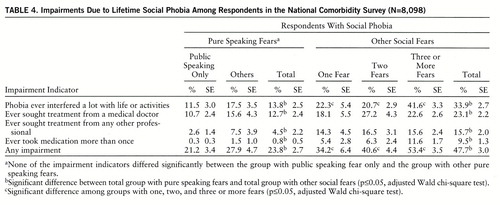

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview includes four indicators of impairment in each diagnostic section: whether the disorder ever interfered a lot with the respondent's life or activities, whether the respondent ever sought treatment from a medical doctor, whether the respondent ever sought treatment from any other professional (e.g., social worker or clergy), and whether the respondent ever took medications more than once for the disorder. Of the respondents with lifetime social phobia, 39.1% endorsed at least one of these impairment statements. As shown in table 4, the percentage of endorsement was approximately twice as high for respondents with nonspeaking fears (47.7% of 388) as for those with pure speaking fears (23.8% of 692) (z=5.9, p<0.001). Within the subsample of respondents with social phobia having at least one nonspeaking fear, furthermore, the endorsement percentage was monotonically related to number of fears: 34.2% of the 92 with one fear, 40.6% of the 171 with two fears, and 53.4% of the 428 with three or more fears (χ2=15.6, df=2, p<0.001).

Sociodemographic Correlates

A previous report on the National Comorbidity Survey (3) documented several sociodemographic correlates of lifetime social phobia, the most powerful being low income, low education, and female gender. Disaggregated analyses showed no specification by subtype for the gender effect. However, there were significant findings for income and education, both of which were significantly inversely related to social phobia with nonspeaking fears (income: χ2=36.2, df=3, p<0.001; education: χ2=88.3, df=3, p<0.001). Social phobia with pure speaking fears, in comparison, was not significantly related to income (χ2=2.6, df=3, p=0.45) and was nonmonotonically related to education; i.e., there were high rates among both high school graduates and those with some college education and low rates both among those with less than a high school education and among college graduates (χ2=29.2, df=3, p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

The finding of two social phobia subtypes is superficially consistent with theoretical speculation (11, 12, 31) and clinical observations that patients with social phobia can be divided into those with predominantly performance-type fears and those who also have a broader range of interactional fears (9, 32, 33). However, there are two important differences between the subtypes found in the National Comorbidity Survey and those found in clinical studies. First, persons with social phobia with pure speaking fears are rare in clinical samples because they have a low rate of service use. As a result, clinical studies have failed to identify the pure-speaking-fear subtype found here. Second, the pure-performance-fear subtype in clinical studies is usually characterized by a larger set of performance fears, such as fear of writing in public and fear of eating in public, in addition to speaking fears, while generalized social phobia is characterized by a combination of performance fears and interactional fears, such as fears of dating, of attending social gatherings, and of speaking with strangers.

We did not find a distinction between the latter two subtypes (broadly defined performance fear versus generalized fear) in the National Comorbidity Survey. Our failure to find this distinction is probably due to the fact that only one of the six questions in the Composite International Diagnostic Interview asked about an interactional fear (fear of talking to people because you might have nothing to say or might sound foolish). This highlights an important limitation in the National Comorbidity Survey for purposes of the current analysis: the survey assessed only six social fears. A much larger set of social fears, including a wider range of performance fears plus interactional fears, is needed in future epidemiologic studies to carry out more fine-grained subtyping of social phobia.

Despite this limitation, it is worth noting that in the National Comorbidity Survey the subtype involving at least one nonspeaking fear was found to be more chronic, comorbid, and impairing than the pure-speaking-fear subtype and that this was especially true for respondents with three or more social fears. The vast majority of survey respondents with this subtype endorsed the statement about the one interactional fear included in the survey. The fact that these people reported the most impairment is consistent with the clinical observation that patients in treatment for social phobia who have fears of most social situations are more impaired than those who have fewer social fears (34). This finding presumably reflects the fact that situations that require public speaking can be avoided by most people with less impairment than situations that require other types of social performance or social interaction.

Our finding that socioeconomic status is inversely related to social phobia with nonspeaking fears could be due either to social causation (socioeconomic success protecting against social phobia), social selection (early-onset social phobia interfering with socioeconomic success), or some combination of these processes. The finding that social phobia with pure speaking fears is more prevalent among those with high school or some college education than either college graduates or people with less than a high school education is most plausibly interpreted as a mixture of processes that include lack of exposure to the phobic stimulus among people with little education (i.e., a low chance of the fear of public speaking ever being activated among people with low education because it is rare for them to be called on to speak in public) and social selection at higher levels of education (i.e., speaking phobia might interfere with subsequent educational attainment among high school graduates).

It is interesting to consider whether the apparently lower degree of impairment among respondents with social phobia with pure speaking fears than among those with other social phobia is simply a matter of number rather than type of fears. There is no way to answer this question definitely in the National Comorbidity Survey because the set of six social fear questions is too brief to permit confidence that people classified as having only one social fear would not have reported others if a longer list had been presented. Nonetheless, it is informative to compare the 35.8% of respondents with social phobia in the survey who were classified as have pure speaking fears with the 8.5% who had only one other fear among the six assessed. A comparison of these two subgroups showed that respondents with pure-speaking-fear social phobia had a weaker family history of the disorders considered here, less comorbidity, and less impairment than the respondents with social phobia who had only one nonspeaking social fear each.

This last result might mean that pure-speaking-fear social phobia is a different type of social phobia than social phobia characterized by nonspeaking fears. It would be a mistake, however, to conclude that social phobia with pure speaking fear is not real social phobia. As other studies have shown (11), some persons with pure-speaking-fear social phobia experience considerable impairment. Furthermore, it is possible that some of these persons experience more subtle forms of impairment than the measures used in the survey were able to detect. As already noted, it would be useful for future epidemiologic surveys to assess a broader range of social situations, both performance and interactional, than the six in the National Comorbidity Survey in order to assess this possibility and provide a rigorous definition of the DSM-IV requirement that generalized social phobia include fears of “most social situations.” Despite this limitation, though, we can draw two useful conclusions from the results reported here. First, a substantial proportion of persons with social phobia in the general population have pure speaking fears, although a more in-depth assessment might show that fears of other social situations are also involved in some cases, while other people with social phobia generally have a greater number of fears that usually involve both performance and interaction. It is not clear from the results reported here whether these two represent distinct subtypes or, rather, different severity thresholds on a single dimension of extensiveness of social fears. It is clear, though, that speaking fears are much more prevalent than the other social fears considered here and that a substantial proportion of people with social phobia meet the criteria exclusively because of speaking fears.

Second, social phobia that involves more extensive fears is more persistent, is associated with more impairment, and is more frequently present with other DSM-III-R disorders than the subtype with pure speaking fears. For these reasons, social phobia involving multiple fears that are not exclusively fears of speaking should be the focus of the most intensive public health interest until more fine-grained subtyping can be done.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The National Comorbidity Survey is a collaborative epidemiologic investigation of the prevalences, causes, and consequences of psychiatric morbidity and comorbidity in the United States supported by NIMH (MH-46376, MH-49098, MH-52861) with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (through a supplement to MH-46376) and the W.T. Grant Foundation (90135190), Ronald C. Kessler, principal investigator. Preparation for this report was also supported by an NIMH Research Scientist Award to Dr. Kessler (MH-00507). Collaborating National Comorbidity Survey sites (and investigators) are as follows: Addiction Research Foundation (Robin Room), Duke University Medical Center (Dan Blazer, Marvin Swartz), Harvard Medical School (Richard Frank, Ronald Kessler), Johns Hopkins University (James Anthony, William Eaton, Philip Leaf), Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry Clinical Institute (Hans-Ulrich Wittchen), Medical College of Virginia (Kenneth Kendler), University of Miami (R. Jay Turner), University of Michigan (Lloyd Johnston, Roderick Little), New York University (Patrick Shrout), State University of New York at Stony Brook (Evelyn Bromet), and Washington University School of Medicine (Linda Cott~ler, Andrew Heath). A complete list of all National Comorbidity Survey publications along with abstracts, study documentation, interview schedules, and the raw National Comorbidity Survey public use data files can be obtained directly from the National Comorbidity Survey home page by using the URL http://www.umich.edu/~ncsum/ on the World Wide Web.

|

|

|

|

Received April 9, 1997; revision received Aug. 18, 1997; accepted Sept. 18, 1997. From the Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School; the Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, Calif.; and the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Address reprint requests to Dr. Kessler, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, 180 Longwood Ave., Boston, MA 02115; [email protected] (e-mail).

FIGURE 1. Kaplan-Meier Curves for Cumulative Time Between Age at Onset and Age at Most Recent Phobic Symptoms (Offset) for Subtypes of Social Phobia in the National Comorbidity Survey (N=8,098)

1 Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Stein MB, Walker JR, Forde DR: Setting diagnostic thresholds for social phobia: considerations from a community survey of social anxiety. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:408–412Link, Google Scholar

3 Magee WJ, Eaton WW, Wittchen H-U, McGonagle KA, Kessler RC: Agoraphobia, simple phobia, and social phobia in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:159–168Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 Schneier FR, Johnson J, Hornig C, Liebowitz M, Weissman M: Social phobia: comorbidity and morbidity in an epidemiologic sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:282–288Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 Davidson JRT, Hughes DC, George LK, Blazer DG: The boundary of social phobia: exploring the threshold. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:975–983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Schneier FR, Heckelman LR, Garfinkel R, Campeas R, Fallon BA, Gitow A, Street L, Del Bene D, Liebowitz MR: Functional impairment in social phobia. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:322–331Medline, Google Scholar

7 Davidson JRT, Hughes DL, George LK, Blazer DG: The epidemiology of social phobia: findings from the Duke Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. Psychol Med 1993; 23:709–718Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Chapman TF, Mannuzza S, Fyer AJ: Epidemiology and family studies of social phobia, in Social Phobia: Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment. Edited by Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR. New York, Guilford Press, 1995, pp 21–39Google Scholar

9 Heimberg RG, Holt CS, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR: The issue of subtypes in the diagnosis of social phobia. J Anxiety Disorders 1993; 7:249–269Crossref, Google Scholar

10 Turner SM, Beidel DC, Townsley RM: Social phobia: a comparison of specific and generalized subtypes and avoidant personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 1992; 101:326–331Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Stein MB: How shy is too shy? Lancet 1996; 347:1131–1132Google Scholar

12 Stein MB, Walker JR, Forde DR: Public speaking fears in a community sample: prevalence, impact on functioning, and diagnostic classification. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:169–174Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13 Kessler RC, Little RJA, Groves RM: Advances in strategies for minimizing and adjusting for survey nonresponse. Epidemiol Rev 1995; 17:192–204Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 World Health Organization: Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 1.0. Geneva, WHO, 1990Google Scholar

15 Wittchen H-U: Reliability and validity studies of the WHO-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res 1994; 28:57–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz MS: The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:979–986Link, Google Scholar

17 Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC: The lifetime co-occurence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:313–321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 Warner LA, Kessler RC, Hughes M, Anthony JC, Nelson CB: Prevalence and correlates of drug use and dependence in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:219–229Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 Wittchen H-U, Kessler RC, Zhao S, Abelson J: Reliability and clinical validity of UM-CIDI DSM-III-R generalized anxiety disorder. J Psychiatr Res 1995; 29:95–110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 Wittchen H-U, Zhao S, Abelson JM, Abelson JL, Kessler RC: Reliability and procedural validity of UM-CIDI DSM-III-R phobic disorders. Psychol Med 1996; 26:1169–1177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21 Kessler RC, Wethington E: The reliability of life events reports in a community survey. Psychol Med 1991; 21:1–16Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624–629Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 Endicott J, Andreasen N, Spitzer RL: Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria, 3rd ed. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1978Google Scholar

24 Kendler KS, Silberg JL, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ: The family history method: whose psychiatric history is measured? Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1501–1504Google Scholar

25 Lazarsfeld PR, Henry NW: Latent Structure Analysis. Boston, Houghton-Mifflin, 1968Google Scholar

26 Eaves LJ, Silberg JL, Hewitt JK, Rutter M, Meyer JM, Neale MC, Pickles A: Analyzing twin resemblance in multisymptom data: genetic applications of a latent class model for symptoms of conduct disorder in juvenile boys. Behav Genet 1993; 23:5–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 Kaplan EL, Meier P: Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Statistical Association 1958; 53:281–284Crossref, Google Scholar

28 Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied Logistic Regression. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1989Google Scholar

29 Woodruff RS, Causey BD: Computerized method for approximating the variance of a complicated estimate. J Am Statistical Association 1976; 71:315–321Crossref, Google Scholar

30 Kish L, Frankel MD: Inferences from complex samples. J Am Statistical Association 1970; 65:1071–1094Crossref, Google Scholar

31 Hazen AL, Stein MB: Clinical phenomenology and comorbidity, in Social Phobia: Clinical and Research Perspectives. Edited by Stein MB. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995, pp 3–42Google Scholar

32 Gelernter CS, Stein MB, Tancer ME, Uhde TW: An examination of syndromal validity and diagnostic subtypes in social phobia and panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1992; 53:23–27Medline, Google Scholar

33 Heimberg RG, Hope DA, Dodge CS, Becker RE: DSM-III-R subtypes of social phobia. J Nerv Ment Dis 1990; 178:172–179Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34 Mannuzza S, Schneier FR, Chapman TF, Liebowitz MR, Klein DF, Fyer AJ: Generalized social phobia: reliability and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:230–237Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar