Criticisms of Kraepelin’s Psychiatric Nosology: 1896–1927

Abstract

Emil Kraepelin’s psychiatric nosology, proposed in the 5th and 6th editions of his textbook published in 1896 and 1899, did not quickly gain worldwide acceptance, but was instead met with substantial and sustained criticism. The authors review critiques of Kraepelin’s work published in his lifetime by Adolf Meyer, Friedrich Jolly, Eugenio Tanzi, Alfred Hoche, Karl Jaspers, and Willy Hellpach. These critics made six major points. First, Kraepelin’s new categories of dementia praecox and manic-depressive insanity were too broad and too heterogeneous. Second, his emphasis on course of illness was misconceived, as the same disease can result in brief episodes or a chronic course. Third, the success of his system was based on the quality of his textbooks and his academic esteem, rather than on empirical findings. Fourth, his focus on symptoms and signs led to neglect of the whole patient and his or her life story. Fifth, Kraepelin’s early emphasis on experimental psychology did not bear the expected fruit. Sixth, Kraepelin was committed to the application of the medical disease model. However, because of the many-to-many relationship between brain pathology and psychiatric symptoms, true natural disease entities may not exist in psychiatry. Most of the ongoing debates about Kraepelin’s nosology have roots in these earlier discussions and would be enriched by a deeper appreciation of their historical contexts. As authoritative as Kraepelin was, and remains today, his was only one among many voices, and attention to them would be well repaid by a deeper understanding of the fundamental conceptual challenges in our field.

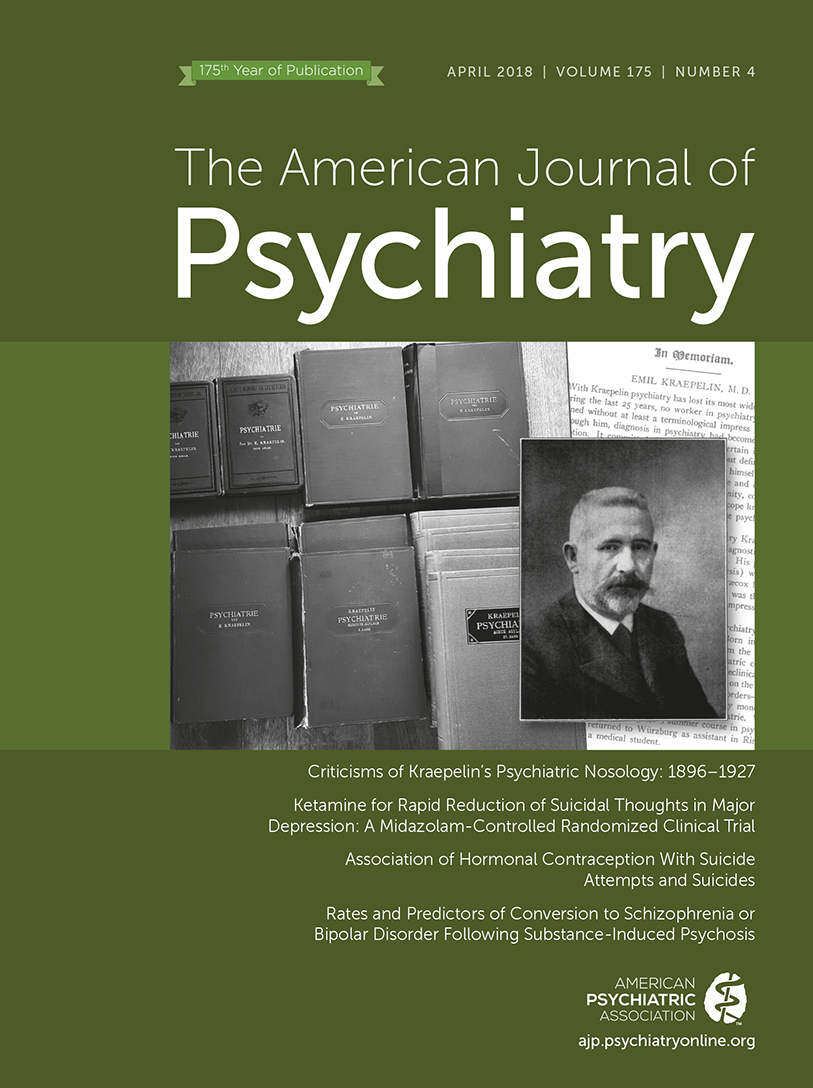

[AJP at 175: Remembering Our Past As We Envision Our Future

April 1927: In Memoriam: Emil Kraepelin, M.D.

Meyer provides an admiring but not uncritical overview of Kraepelin’s career and contributions to psychiatry. “It was the unflinchingly psychiatric orientation of the man,” he wrote, “that impressed and attracted physicians and students.” (Am J Psychiatry 1927; 83:748–755)]