Early Risk Factors and Developmental Pathways to Chronic High Inhibition and Social Anxiety Disorder in Adolescence

Abstract

Objective

Evidence suggests that chronic high levels of behavioral inhibition are a precursor of social anxiety disorder. The authors sought to identify early risk factors for, and developmental pathways to, chronic high inhibition among school-age children and the association of chronic high inhibition with social anxiety disorder by adolescence.

Method

A community sample of 238 children was followed from birth to grade 9. Mothers, teachers, and children reported on the children's behavioral inhibition from grades 1 to 9. Lifetime history of psychiatric disorders was available for the subset of 60 (25%) children who participated in an intensive laboratory assessment at grade 9. Four early risk factors were assessed: female gender; exposure to maternal stress during infancy and the preschool period; and at age 4.5 years, early manifestation of behavioral inhibition and elevated afternoon salivary cortisol levels.

Results

All four risk factors predicted greater and more chronic inhibition from grades 1 to 9, and together they defined two developmental pathways. The first pathway, in girls, was partially mediated by early evidence of behavioral inhibition and elevated cortisol levels at age 4.5 years. The second pathway began with exposure to early maternal stress and was also partially mediated by childhood cortisol levels. By grade 9, chronic high inhibition was associated with a lifetime history of social anxiety disorder.

Conclusions

Chronic high levels of behavioral inhibition are associated with social anxiety disorder by adolescence. The identification of two developmental pathways suggests the potential importance of considering both sets of risk factors in developing preventive interventions for social anxiety disorder.

Behavioral inhibition, an early temperamental characteristic, is a precursor of anxiety disorders, especially social anxiety disorder (1–3). In younger children, inhibition is characterized by an elevated fear response to both social and nonsocial novelty; by school age, it is characterized primarily by social reticence (4). Children who are chronically inhibited are at greatest risk for the development of anxiety disorders (3, 5). Extreme school-age inhibition shares much in common with social anxiety disorder (6), including fear of meeting or interacting with unfamiliar peers and adults, and recent evidence suggests that it is chronic inhibition that for some individuals evolves into social anxiety disorder (7).

Considerable research has focused on the chronicity of childhood inhibition. Studies have shown that extreme childhood inhibition is moderately enduring and heritable (4, 8, 9), suggesting that it may represent a marker of genetically transmitted susceptibility to later chronic inhibition and social anxiety disorder (10). However, there is also considerable evidence of instability in inhibition (11), especially in unselected samples of children (as opposed to children with extreme symptoms) who are studied over longer intervals encompassing multiple developmental periods (12). Some studies have also found greater chronicity among girls than boys (2, 5, 9, 12), although the findings are inconsistent (13). Previous findings also suggest that factors other than early inhibition play important roles in the development of chronic inhibition and social anxiety disorder (14).

One candidate biological substrate is elevated activity of the limbic system, which is associated with the generation of fear (4). Imaging studies in monkeys and humans suggest that individual differences in limbic system activity (amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis) are associated with temperamental inhibition and anxiety-related behaviors (15, 16). Inhibition is linked with physiological reactivity across systems regulated by the central nucleus of the amygdala, including the neuroendocrine response system (17). Of particular interest are findings suggesting that increased pituitary-adrenal activity, assessed by salivary cortisol levels, is associated with extreme childhood inhibition (4, 18), although increased cortisol levels have also been linked with other temperamental styles (19, 20). In the same sample of children we report on here, our group previously showed that preschoolers with elevated afternoon cortisol levels, especially girls, showed higher levels of later inhibition during the transition to primary school (21). However, the role of cortisol in the development of chronic school-age inhibition has not been investigated.

Early environmental factors also play a role in the development of inhibition. Monkeys exposed to early environmental perturbations and negative maternal behaviors tend to develop increased hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal reactivity and stable fear-related behaviors (22, 23). Studies of young children also suggest that maternal behaviors, including being overly solicitous as well as negative behaviors (e.g., low engagement, hostility) associated with maternal depression or distress, might influence the development of elevated cortisol levels (24, 25) and early inhibition (26, 27). However, little is known about the effects on childhood cortisol levels and inhibition of a broader array of family adversities that may create stressful caretaking environments. In the same sample of children we report on here, our group previously showed that exposure to early maternal stress, assessed across multiple domains, prospectively predicted elevated cortisol levels when the children were age 4.5 years (28). However, a cross-sectional study (29) showed no association of psychosocial adversity with inhibition among young children. To our knowledge, no prospective studies have been conducted on the effect of such family-wide stressors on the development of chronic school-age inhibition.

In this study, we aimed to identify the early risk factors for, and longitudinal pathways to, chronic high inhibition across grades 1 to 9 (ages 7 to 15). We also estimated the association of chronic inhibition with lifetime history of social anxiety disorder for a subset of children at grade 9. Four potential early risk factors were considered: child gender; exposure to maternal stress during the infancy and preschool periods; and at child age 4.5 years, observations of behavioral inhibition and afternoon cortisol levels. We hypothesized that all four factors would be associated with the development of chronic high school-age inhibition; that early evidence regarding behavioral inhibition and cortisol levels would play mediating roles in defining developmental pathways; and that chronic high inhibition would be associated with social anxiety disorder by adolescence.

Method

Participants

The data were drawn from a larger longitudinal study, the Wisconsin Study of Families and Work (30). A sample of 570 pregnant women over age 18 who were living with the baby's biological father were recruited from prenatal clinics in two cities during the second trimester of pregnancy. Follow-up assessments were conducted when the children were in infancy (at 1, 4, and 12 months), at preschool age (ages 3.5 and 4.5 years), and at grades 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9; teachers participated beginning at grade 1. At grade 1, 468 (82%) of the families remained in the study. However, because of budgetary constraints, the full grade 1 assessment (which required home visits) was conducted only on one-half of the first cohort (N=100) and the complete second cohort (N=197) of families living within a 4-hour driving distance of the project offices. Of these 297 families and teachers who participated in the full grade 1 assessment, the present study included the 238 for whom complete multi-informant inhibition data through grade 9 were available (missing data were primarily due to home schooling and school or teacher refusal). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Informed consent was obtained from adults at each assessment; beginning at grade 5, children provided informed assent.

The sample of 238 children consisted of 111 boys and 127 girls, 11% of them ethnic minorities. At recruitment (1990–1991), the mothers ranged from 20 to 41 years of age (median=30 years); 96% were married. One percent of the mothers had less than a high school degree, 40% were high school graduates, 38% were college graduates, and 21% had education beyond college; the fathers' educational level had a similar distribution. Annual family income ranged from $7,500 to over $200,000 (median=$49,000, comparable to the average family income in Wisconsin) (31). There were no demographic differences between the 238 participating families and the remainder of the original 570 families, with two exceptions: participating mothers were 1 year older on average than nonparticipating mothers (mean=29.97 years [SD=4.20] compared with mean=28.94 years [SD=4.43]; t=–2.80, df=568, p=0.005), and participating families had a higher annual income on average than nonparticipating families (mean=$52,232 [SD=$22,797] compared with mean=$48,106 [SD=$23,853]; F=4.27, df=1, 564, p=0.039).

Measures

Maternal stress was assessed in the infancy and preschool periods with maternal reports of five domains. 1) Maternal depression was assessed by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (32); alpha coefficients exceeded 0.85 for all assessments. 2) Family expressed anger was assessed with the average of three items tapping marital conflict and scores for anger expression and the negative subscale of the Family Expressiveness Questionnaire (33–35); all alpha values were >0.70. 3) Parenting stress was calculated from scores on the competence and child-reinforces-parent subscales of the Parenting Stress Index and the average of three negative items (e.g., "I often feel angry with my child") from the Child-Rearing Practices Report (34, 36, 37); all alpha values were >0.65. 4) Role overload was calculated from the role restriction subscale of the Parenting Stress Index, and the average of five items from the role overload scale (e.g., feeling "pulled apart by conflicting obligations") (34, 36, 37); all alpha values were >0.75. 5) Financial stress was calculated as the average of four items (e.g., "difficulty making monthly payments"); all alpha values were >0.70. Separately for the infancy and preschool periods, composites were constructed using principal components analysis, where the first component accounted for at least 50% of the variance and all factor loadings exceeded 0.50. The two resulting composites were highly correlated (r=0.73) and thus were averaged.

Children's behavioral inhibition at age 4.5 years was assessed from videotaped observations of a 2-hour home visit conducted by two research assistants. The visit included entrance to the home, saliva collection, cognitive testing, and a series of emotion-eliciting tasks (38), all used to measure the child's reactions to unfamiliar people, objects, and test procedures. After the visit, the research assistants independently reviewed the videotape once for the entire assessment and rated the children on four 5-point items assessing global shyness, initiative with tasks, exploration of unfamiliar objects, and social engagement with the research assistants (all kappa values ≥0.80). Each item was averaged across the two research assistants, and the four averaged items were combined into a single composite score using principal components analysis (65% of the variance was accounted for; all factor loadings >0.71).

Children's salivary cortisol levels at age 4.5 years were assessed with saliva samples (passive drool) collected by parents on three consecutive afternoons. Eighty-six percent of the samples were collected in the target period between 3:00 p.m. and 7:00 p.m., and the remainder were collected earlier in the afternoon. Cortisol was assessed with the Pantex RIA (Santa Monica, Calif.) modified for saliva. The detection limit of the assay (ED80) was 0.03 mg/dl. The mean interassay variation was 7.4%, and the mean intra-assay variation was 3.8%. Based on previous analyses (21, 28) showing that only antibiotics and cold or allergy medications affected cortisol values in this sample, medication use was coded 1 if the child was currently on any of these medications and 0 otherwise. To control for time of collection and medication use, the log-transformed cortisol values were residualized for hour of collection and medications.

Children's school-age inhibition was assessed from interviews with mothers, teachers, and children during the spring of grades 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9. Adults completed the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire (39) social inhibition scale (five items, such as "shy asking peers to play," "shy with unfamiliar adults"); all alpha values were >0.74. At grade 1, children were asked a parallel set of items from the Berkeley Puppet Interview social scales (40) (α=0.67). At subsequent grades, the Berkeley Puppet Interview was modified to an age-appropriate questionnaire format; all alpha values were >0.71. Multi-informant scores were computed at each assessment using a principal components analysis-based approach (41) in which the first component measures the core characteristic of interest (here, inhibition), defined as what the three reports shared in common (i.e., all positive loadings >0.50), and the second and third components distinguish the sources of error that result from reporters' differing perspectives (i.e., child self-view versus adult view) and contexts (i.e., home versus school). To construct a longitudinal inhibition score reflecting both level and chronicity, the first component scores of the principal components analysis were used to categorize children at each assessment as being in the lower 25% (score=1), the middle 50% (score=2), or the upper 25% (score=3) of inhibition; these scores were summed over the five assessments, resulting in a longitudinal score ranging from 5 (in the lower 25% at all times) to 15 (in the upper 25% at all times).

Lifetime DSM-IV diagnoses were obtained with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) (42) for the subset of the children who participated in an intensive laboratory assessment at grade 9 (N=60; 25%). Recruitment was based on living in close proximity to the laboratory and reporting no exclusionary criteria for functional MRI (e.g., metal orthodontics); there was no significant difference on the longitudinal inhibition score between these children and the remaining 178 children (mean=10.30 [SD=2.95] compared with mean=9.87 [SD=2.63]). A board-certified child psychiatrist (M.J.S.) with expertise in the K-SADS-PL trained and supervised a child psychiatrist and a clinical child psychologist in its administration. Children were interviewed first and mothers second, with additional interviewing conducted when their responses related to diagnostic criteria disagreed. All K-SADS-PL interviews were reviewed by M.J.S. and the administering clinician, and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data Analysis

Data analyses addressed two questions. First, Spearman correlations identified the early risk factors for chronic high inhibition, and a hierarchical multiple regression analysis defined the longitudinal linkages among the risk factors. Child gender and exposure to early maternal stress were included in the first step of the regression analysis. Next, to identify possible mediators and moderators, childhood behavioral inhibition and afternoon cortisol levels at age 4.5 years were entered, together with the four pairwise interactions of child gender and exposure to maternal stress with each of the two 4.5-year variables; no significant interactions were found. A dichotomous variable was also included to assess any effect of psychotropic medication use at grade 9 (N=14; 6%); no significant effect was found. Second, among the subset of children with lifetime psychiatric data, a chi-square analysis ascertained differences in DSM-IV diagnoses according to level and chronicity of school-age inhibition; t tests examined differences in risk factors and school-age inhibition for children with and without a lifetime history of social anxiety disorder.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

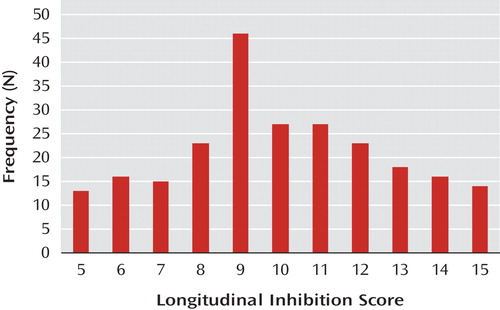

The distribution of the longitudinal inhibition score is shown in Figure 1 (mean=9.98, SD=2.71). For the chi-square analysis only, these scores were collapsed to form five groups, where chronic inhibition was defined as evidencing the same level (low, middle, high) for at least four of the five assessments and never evidencing a nonadjacent level. By this definition, 55% of the children evidenced chronic inhibition, including all children in the chronic high (scores of 15 or 14) and chronic low (scores of 5 or 6) groups and three-fourths of those in the middle (scores of 9, 10, or 11) group. None of the children in the low-middle (scores of 7 or 8) or middle-high (scores of 12 or 13) groups evidenced chronicity.

aScores are summed across the five assessments (grades 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9), where, at each assessment, 1=lower 25%, 2=middle 50%, and 3=upper 25% of the distribution of inhibition.

Identification of Early Risk Factors and Pathways to Chronic High Inhibition

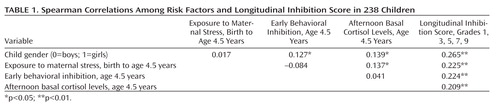

All four early risk factors were significantly correlated with the longitudinal inhibition score (Table 1; see Table S1 in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article for correlations with inhibition at each grade). As hypothesized, chronic high inhibition was associated with being female, exposure to higher levels of early maternal stress, and, at age 4.5 years, higher levels of behavioral inhibition and afternoon cortisol. Each pair of risk factors within a time period (i.e., child gender and exposure to maternal stress beginning at birth, and behavioral inhibition and cortisol levels at age 4.5 years) were uncorrelated; however, there were significant correlations between the earlier risk factors and those at age 4.5 years, possibly reflecting mediational processes.

|

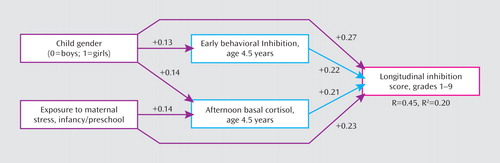

The hierarchical multiple regression analysis identified two mediational chains (Figure 2). The first chain began with the association of child gender with longitudinal inhibition (β=1.34, p<0.001), which at a trend level (Sobel's test, p=0.069) was partially mediated by early behavioral inhibition and cortisol levels at age 4.5 years (the effect was reduced but remained significant; β=1.13, p=0.001). The second chain began with exposure to early maternal stress (β=0.64, p=0.001), which was partially mediated (β=0.61, p=0.001; Sobel's test, p=0.048) by children's cortisol levels at age 4.5 years.

aCoefficients are bivariate Spearman correlations (see Table 1). All correlations are significant at p<0.05.

Association of Chronic High Inhibition With Social Anxiety Disorder

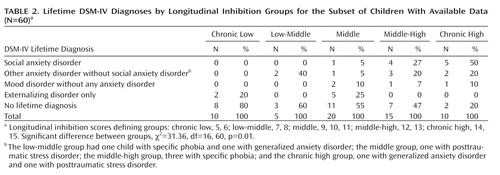

Among the 60 children for whom data were available on lifetime DSM-IV diagnoses, significant differences were observed in diagnostic status among the five longitudinal inhibition chronicity groups (χ2=31.36, df=16, 60, p=0.01) (Table 2). Whereas 80% of the children in the chronic high group received at least one lifetime psychiatric diagnosis, all in the internalizing (anxiety or mood) domain, the percentage decreased across the groups to only 20% in the chronic low group, all in the externalizing domain. Notably, 50% of the children in the chronic high group received a lifetime diagnosis of social anxiety disorder, compared with 27% in the middle-high group, 5% in the middle group, and none in the low-middle and chronic low groups. Among the three higher chronicity groups, there were few differences in other anxiety disorders (predominantly specific phobias) or mood disorders.

|

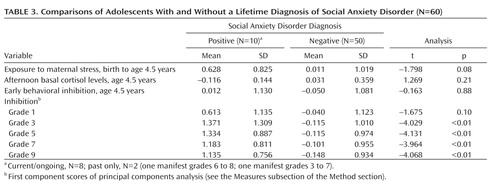

Because of the overlapping time intervals over which inhibition (and risk factor) ratings and lifetime diagnoses of social anxiety disorder were obtained, additional analyses were conducted to substantiate the prospective nature of this association. Comparisons of adolescents with and without a lifetime diagnosis of social anxiety disorder showed that there were no significant group differences for the early risk factors or grade 1 inhibition, but adolescents diagnosed with social anxiety disorder had significantly higher inhibition scores beginning at grade 3 (Table 3). This pattern corresponds closely with the interview descriptions of the adolescents diagnosed with social anxiety disorder as being "always" shy since very early childhood, with the defining clinical features of significant distress and impairment manifesting later, in elementary or middle school, when the demands of social relationships, including performance situations, increased.

|

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to identify the early risk factors for, and developmental pathways to, chronic high levels of school-age inhibition and its association with social anxiety disorder in adolescence. As hypothesized, all four early factors significantly predicted chronic high inhibition. Although behavioral inhibition and cortisol levels at 4.5 years were unrelated, each played a mediating role in pathways to later chronic high levels of inhibition. Chronic high levels of inhibition were significantly associated with a lifetime history of social anxiety disorder by grade 9.

These results extend those of previous studies of the chronicity of childhood inhibition, focusing on early behavioral inhibition as a risk factor for the development of chronic high school-age inhibition and its association with social anxiety disorder by adolescence. Although the correlation of early behavioral inhibition with later chronic high inhibition (Spearman correlation=0.224) was lower than two-point stability estimates found in some studies of children selected for extreme inhibition (43), it was consistent with previous studies of unselected children assessed over longer intervals and when measures of inhibition differed across developmental periods (i.e., observations of early inhibition and informant reports of school-age inhibition) (12). The specific association of chronic high levels of school-age inhibition with social anxiety disorder by grade 9 was consistent with previous findings showing that it is the chronicity of high childhood inhibition that makes it most likely to evolve into social anxiety disorder (7).

Two developmental pathways were identified. The "gender pathway" suggests that girls are at greater risk for developing chronic high inhibition, in part because they evidence greater inhibition and afternoon cortisol levels as preschoolers. It has been suggested that these gender differences may reflect differences in cultural expectations and socialization patterns such that some degree of inhibition and increased stress responsivity is considered gender appropriate in girls, whereas in boys, it is less likely to be reinforced and may even be discouraged (12). However, it should be noted that these mediating effects were statistically marginal, and previous findings of the association of gender with chronic inhibition are inconsistent (2, 5, 12, 13).

The "stress pathway" highlighted that children exposed to greater maternal stress beginning at birth are at greater risk for developing chronic high inhibition, in part because they evidence increased afternoon cortisol levels as preschoolers. Our group previously reported that both early stress exposure and preschool cortisol levels predicted children's overall mental health symptoms in grade 1 (28). Previous research has established the associations of numerous interrelated components of maternal stress, including those assessed here, with children's internalizing and externalizing problems (44–46). Thus, this may be a pathway to more generalized mental health problems and not as specific to chronic high inhibition as the pathway that includes early behavioral inhibition.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the sample was relatively homogeneous, reflecting primarily Caucasian middle-class families living in the Midwest. Second, we did not have diagnostic information for the full sample of children. Third, the longitudinal model explained one-fifth of the variance in chronic high inhibition, suggesting that there are other important risk factors that we did not assess, including family psychiatric history, child cognitive factors, other child affective and regulatory traits, specific parenting behaviors, and nonshared environmental factors (e.g., adverse life events) (47). Finally, because we defined chronic high inhibition by the number of assessments at which children were in the upper 25%, we did not take advantage of analytic techniques that would allow for missing data longitudinally as well as examination of other patterns of change in inhibition over time.

Despite these limitations, the findings highlight early risk factors comprising two developmental pathways to chronic high school-age inhibition and the specific association with a lifetime history of social anxiety disorder by adolescence. The results suggest that a trajectory of high inhibition may begin with the difficulties experienced by girls who are more likely to be temperamentally inhibited, and all children exposed to early maternal stress, who are more likely to evidence increased cortisol levels as they face the new social challenges associated with the transition to school and the progressive shift from family to peer relationships. Across the school years, the increasingly complex demands of social relationships may contribute to heightened levels of distress and functional impairment, demarcating the shift from chronic high inhibition to the clinically significant symptoms of social anxiety disorder. If confirmed, such a developmental model has implications for both prevention and intervention strategies aimed at reducing the risk of social anxiety disorder. Prevention strategies prior to the school transition might target the modifiable risk factor of maternal stress, and intervention strategies after the school transition might target the social competencies of extremely inhibited children to reduce the risk of chronic high levels of inhibition evolving into social anxiety disorder.

1 : Behavioral inhibition in preschool children at risk is a specific predictor of middle childhood social anxiety: a five-year follow-up. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2007; 28:225–233 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 : Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38:1008–1015 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 : Does shy-inhibited temperament in childhood lead to anxiety problems in adolescence? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:461–468 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4 : Biological bases of childhood shyness. Science 1988; 240:167–171 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 : Stable behavioral inhibition and its association with anxiety disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:103–111 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 : Shyness: relationship to social phobia and psychiatric disorders. Behav Res Ther 2003; 41:209–221 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7 : Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48:1–8 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 : Continuity and change in inhibited and uninhibited children. Child Dev 2002; 73:1474–1485 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 : The heritability of inhibited and unhibited behavior: a twin study. Dev Psychol 1992; 28:1030–1037 Crossref, Google Scholar

10 : The corticotropin-releasing hormone gene and behavioral inhibition in children at risk for panic disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 57:1485–1492 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 : Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: multiple levels of a resilience process. Dev Psychopathol 2007; 19:729–746 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12 : Stability of inhibition in a Swedish longitudinal sample. Child Dev 1994; 65:138–146 Crossref, Google Scholar

13 : Temperamental contributions to social behavior: the moderating roles of frontal EEG asymmetry and gender. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:68–74 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14 : High risk studies and developmental antecedents of anxiety disorders. Am J Med Genetics 2008; 148:99–117 Crossref, Google Scholar

15 : Brain regions associated with the expression and contextual regulation of anxiety in primates. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 58:796–804 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16 : Inhibited and uninhibited infants "grown up": adult amygdalar response to novelty. Science 2003; 300:1952–1953 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17 : Behavioral inhibition: linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annu Rev Psychol 2005; 56:235–262 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18 : Behavioral and neuroendocrine responses in shy children. Dev Psychobiol 1997; 30:127–140 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19 : Temperament, social competence, and adrenocortical activity in preschoolers. Dev Psychobiol 1997; 31:65–85 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20 : Shyness is a necessary but not sufficient condition for high salivary cortisol in typically developing 10-year-old children. Pers Individ Dif 2007; 43:1541–1551 Crossref, Google Scholar

21 : Salivary cortisol as a predictor of socioemotional adjustment during kindergarten: a prospective study. Child Dev 2002; 73:75–92 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22 : Persistent elevations of cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of corticotropin-releasing factor in adult nonhuman primates exposed to early-life stressors: implications for the pathophysiology of mood and anxiety disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93:1619–1623 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23 : Early adverse experience as a developmental risk factor for later psychopathology: evidence from rodent and primate models. Dev Psychopathol 2001; 13:419–449 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 : Maternal and child contributions to cortisol response to emotional arousal in young children from low-income, rural communities. Dev Psychol 2008; 44:1095–1109 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 : A longitudinal study of children of depressed mothers: psychobiological findings related to stress, in Advancing Research on Developmental Plasticity: Integrating the Behavioral Sciences and the Neurosciences of Mental Health. Edited by Hann DMHuffman LCLederhendler KKMinecke D. Bethesda, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1998 Google Scholar

26 : Predicting social wariness in middle childhood: the moderating roles of childcare history, maternal personality, and maternal behavior. Soc Dev 2008; 17:471–487 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27 : Stability and social-behavioral consequences of toddlers' inhibited temperament and parenting behaviors. Child Dev 2002; 73:483–495 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28 : Maternal stress beginning in infancy may sensitize children to later stress exposure: effects on cortisol and behavior. Biol Psychiatry 2002; 52:776–784 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29 : Lack of association between behavioral inhibition and psychosocial adversity factors in children at risk for anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:547–555 Link, Google Scholar

30 : Maternity leave and women's mental health. Psychol Women Q 1995; 19:257–285 Crossref, Google Scholar

31 US Census Bureau, Housing and Household Economic Statistics Division: Median income for 4-person families, by state. US Census Bureau, 2008. http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/4person.html Google Scholar

32 : The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. J Applied Psychol Measurement 1977; 1:385–401 Crossref, Google Scholar

33 : Family socialization of emotional expression and nonverbal communication styles and skills. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986; 51:827–836 Crossref, Google Scholar

34 : Preliminary Manual for the Role-Quality Scales. Wellesley, Mass, Wellesley College, Center for Research on Women, 1989 Google Scholar

35 : The experience, expression, and control of anger, in Health Psychology: Individual Differences and Stress. Edited by Janisse MP. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1988, pp 89–108 Google Scholar

36 : Parenting Stress Index. Charlottesville, Va, Pediatric Psychology Press, 1986 Google Scholar

37 : The Child-Rearing Practices Report (CRPR): A Set of Q Items for the Description of Parental Socialization Attitudes and Values. Berkeley, Calif, Institute of Human Development, 1965 Google Scholar

38 : Preliminary Manual for the Preschool Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery, version 1.0.

39 : The confluence of mental, physical, social, and academic difficulties in middle childhood, II: developing the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:588–603 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40 : Manual for the Berkeley Puppet Interview: Symptomatology, Social, and Academic Modules (BPI 1.0). Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh, MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Psychopathology and Development, 2003 Google Scholar

41 : A new approach to integrating data from multiple informants in psychiatric assessment and research: mixing and matching contexts and perspectives. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:1566–1577 Link, Google Scholar

42 : Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:980–988 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43 : Behavioral inhibition, in Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Edited by Morris TLMarch JS. New York, Guilford, 2004, pp 27–58 Google Scholar

44 : Exploring risk factors for the emergence of children's mental health problems. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:1246–1256 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45 : Family discord, parental depression, and psychopathology in offspring: ten-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:402–409 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46 : Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol Bull 2002; 128:330–366 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47 : The etiology of social phobia: empirical evidence and an initial model. Clin Psychol Rev 2004; 24:737–768 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar