Countertransference Phenomena and Personality Pathology in Clinical Practice: An Empirical Investigation

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study provides initial data on the reliability and factor structure of a measure of countertransference processes in clinical practice and examines the relation between these processes and patients’ personality pathology. METHOD: A national random sample of 181 psychiatrists and clinical psychologists in North America each completed a battery of instruments on a randomly selected patient in their care, including measures of axis II symptoms and the Countertransference Questionnaire, an instrument designed to assess clinicians’ cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses in interacting with a particular patient. RESULTS: Factor analysis of the Countertransference Questionnaire yielded eight clinically and conceptually coherent factors that were independent of clinicians’ theoretical orientation: 1) overwhelmed/disorganized, 2) helpless/inadequate, 3) positive, 4) special/overinvolved, 5) sexualized, 6) disengaged, 7) parental/protective, and 8) criticized/mistreated. The eight factors were associated in predictable ways with axis II pathology. An aggregated portrait of countertransference responses with narcissistic personality disorder patients provided a clinically rich, empirically based description that strongly resembled theoretical and clinical accounts. CONCLUSIONS: Countertransference phenomena can be measured in clinically sophisticated and psychometrically sound ways that tap the complexity of clinicians’ reactions toward their patients. Countertransference patterns are systematically related to patients’ personality pathology across therapeutic approaches, suggesting that clinicians, regardless of therapeutic orientation, can make diagnostic and therapeutic use of their own responses to the patient.

Freud first introduced the concept of countertransference in 1910, noting that the patient’s influence on the analyst’s unconscious feelings can interfere with treatment. This early and relatively narrow view of countertransference as an impediment to treatment prevailed in the psychoanalytic literature for several decades. Over time, however, theorists broadened the concept, recognizing that the clinician’s reactions to the patient (conscious and unconscious, emotional and cognitive, intrapsychic and behavioral) may have diagnostic and therapeutic relevance and can, if properly used, facilitate rather than inhibit treatment (1–5).

According to this expanded view, just as the patient’s behaviors with the therapist could provide in vivo insight into his or her repetitive interpersonal patterns and associated thoughts, feelings, and motives, so, too, could the clinician’s responses to the patient provide insight into patterns the patient wittingly or unwittingly evokes from significant others. Klein (6) suggested that the patient may induce the clinician to experience the feelings that the patient is having trouble acknowledging (7) or may draw the clinician into enactments that reflect the patient’s enduring expectations of relationships (8, 9). Sandler (10) introduced the concept of role responsiveness, in which the therapist acts in accordance with a role that is part of a relationship paradigm the patient unconsciously re-creates with the therapist. Wachtel (11, 12) proposed the similar concept of cyclical psychodynamics, by which patients’ fears, wishes, expectations, and behaviors often create self-fulfilling prophecies.

Although the clinical literature on countertransference is rich and rapidly expanding, the corresponding empirical literature is limited (13–17). Research with largely nonclinical samples has provided indirect support for some of these ideas, demonstrating that depressed people tend to elicit criticism from significant others that matches their own self-criticism (18) and that people who are sensitive to rejection tend (through needy, angry, and otherwise distancing behavior) to elicit rejection and hence to confirm and reinforce their internal working models of relationships (19). Giesler and colleagues (20) demonstrated that some of these processes occur in clinical settings as well. A series of analogue studies (21–26) attempted to operationalize the concept of countertransference, defining countertransference responses as therapists’ reactions to patients that are based on the therapists’ unresolved conflict and operationalizing countertransference in terms of avoidant behaviors (e.g., disapproval, silence, ignoring, mislabeling, and changing the topic). Najavits and colleagues (27) developed the Ratings of Emotional Attitudes to Clients by Treaters scale, a clinically subtle measure of countertransference designed primarily to study therapists’ response to patients in treatment for substance abuse.

The present study provides initial data on the reliability and factor structure of a clinician-report measure of countertransference processes designed to assess countertransference, broadly defined to include the range of cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses therapists have to their patients. Although the concept of countertransference emerged from psychoanalytic theory and practice, our goal was to devise a measure that could be used by clinicians of any theoretical orientation, so that we could assess the extent to which particular countertransference responses are specific to certain forms of therapy and so that clinicians of any orientation who are trying to get a better diagnostic sense of the patient or a better understanding of what is happening in the therapeutic dyad can make use of the instrument by comparing their own responses to normed psychometric data. Our primary aims were 1) to describe the factor structure and reliability of a broadband measure of countertransference phenomena and 2) to examine associations between countertransference phenomena and patients’ personality pathology. Thus, our goals were to provide both initial validity data for the measure and a test of clinically derived hypotheses that have never been put to empirical test. In addition, to illustrate the potential clinical and empirical uses of the instrument, we derived a prototype of the “average expectable countertransference response” to patients with narcissistic personality disorder.

Method

Participants

Participants were 181 clinicians who constituted a random national sample of experienced psychiatrists and psychologists from the membership registers of the American Psychiatric Association and American Psychological Association. We requested mailing lists of clinicians with at least 3 years’ postlicensure or postresidency experience who indicated that they performed at least 10 hours per week of direct patient care. As in prior research with this method, psychologists responded at a substantially higher rate than did psychiatrists to the solicitation, allowing us to assess for biases imposed by differential training or response rates. We found no differences between patients described by psychologists and those described by psychiatrists on any variable of interest despite a roughly 3:1 response rate ratio. (Variables of interest included age, sex, race, socioeconomic status, education level, treatment length, and countertransference factor scores [14 t tests, not significant at p<0.01].) We also compared the patients of this sample of clinicians to those of the first 181 clinicians in another sample with whom we used a similar method but paid a substantially higher honorarium and obtained a correspondingly higher response rate (>30%) for the psychiatrists; we found no differences between the samples of patients. Together, these data suggest that any potential biases in the tendency to respond had minimal impact on the representativeness of the sample (see also the discussion of limitations in the Discussion section).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To obtain a cross-section of psychotherapy patients seen in clinical practice, we asked clinicians to describe a nonpsychotic patient at least 18 years old whom they had treated for a minimum of eight sessions (to maximize the likelihood that they would know the patient well enough to provide a reasonably accurate description of the patient). To minimize selection biases, we directed clinicians to consult their calendar to select the last patient they saw during the prior week who met study criteria. Each clinician described only one patient in order to minimize rater-dependent biases. Clinicians received a modest honorarium ($85) for a procedure that took 3–4 hours to complete, with a response rate of approximately 10%.

Procedure

Clinicians could participate either by pen-and-paper forms or on an interactive web site (http://www.psychsystems.net). Web versus paper participants did not differ on any variable studied here (e.g., countertransference factor scores; eight t tests). Clinicians provided no identifying information about the patient (such as name, initials, or social security number) and were instructed to use only information already available to them from their contacts with the patient so that data collection would not compromise patient confidentiality or interfere in any way with ongoing clinical work.

Measures

We employed a number of measures in standardized sequence. We describe those of relevance to the present study here.

Clinical Data Form

The Clinical Data Form (see references 28, 29) assesses a range of variables relevant to demographics, diagnosis, and etiology. Clinicians first provide basic demographic data on themselves, including discipline (psychiatry or psychology), theoretical orientation, employment sites (e.g., private practice, inpatient unit, school), and sex, and then provide data on the patient’s age, sex, race, education level, socioeconomic status, axis I diagnoses, etc. After completing basic demographic and diagnostic questions, clinicians complete ratings of the patient’s adaptive functioning, developmental history, and family history (which will not be described further here).

Axis II diagnosis

To assess axis II disorders, we asked clinicians to rate as present or absent each criterion of each of the DSM-IV axis II diagnoses, randomly ordered. This procedure provides both a categorical diagnosis of each disorder (obtained by applying DSM-IV cutoffs) and a dimensional measure (number of criteria met for each disorder). Our research group and others have successfully used similar measures in a number of investigations (29–31).

Countertransference Questionnaire

The Countertransference Questionnaire (32) is a 79-item clinician-report questionnaire designed to provide a normed, psychometrically valid instrument for assessing countertransference patterns in psychotherapy for both clinical and research purposes. (The instrument can be downloaded at http://www.psychsystems.net/lab.) The items measure a wide range of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors expressed by therapists toward their patients. We derived the 79 items by reviewing the clinical, theoretical, and empirical literature on countertransference and related variables and by soliciting the advice of several experienced clinicians to review the initial item set for comprehensiveness and clarity. We wrote the items in everyday language, without jargon, so that the instrument could be used comparably by clinicians of any theoretical orientation. Items assess a range of responses, from relatively specific feelings (e.g., “I feel bored in sessions with him/her.”) to complex constructs such as “projective identification” (e.g., “More than with most patients, I feel like I’ve been pulled into things that I didn’t realize until after the session was over.”).

Results

Sample Characteristics

The clinician sample consisted of 141 (77.9%) psychologists and 40 (22.1%) psychiatrists; 58.6% (N=106) of the clinicians were male. The majority saw patients in private practice (N=145, 80.1%), but they also worked in other settings, including hospital (N=57, 31.5%), forensic (N=15, 8.3%), clinic (N=14, 7.7%), or school (N=9, 5.0%) settings. (As might be expected, psychiatrists were more likely to have primary or secondary employment in hospital settings.) The most common self-reported theoretical orientations included psychodynamic (N=73, 40.3%), eclectic (N=55, 30.4%), and cognitive behavioral (N=37, 20.4%).

Reflecting our efforts to obtain a patient sample stratified by sex, about one-half of the patients were male and one-half were female, with an average age of 40.5 years (SD=13.4). The sample was predominantly Caucasian (N=168, 92.8%). Most were middle class (N=102, 56.4%), with 2.8% (N=5) rated as poor, 24.3% (N=44) as working class, and 16.6% (N=30) as upper class. The mean Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score was 58.0 (SD=12.9). Length of treatment averaged 19 months (SD=30.0), with a median of 13 months, indicating that the clinicians knew the patients very well. The most common diagnoses reported by the clinicians were major depressive disorder (N=89, 49.2%), dysthymic disorder (N=68, 37.6%), generalized anxiety disorder (N=46, 25.4%), and adjustment disorder (N=45, 24.9%).

Factor Structure of the Countertransference Questionnaire

To identify the factor structure of the Countertransference Questionnaire, we first subjected the items to a principal-component analysis using Kaiser’s criteria (eigenvalues >1). We used the scree plot, percentage of variance accounted for, and parallel analysis (33–35) to select the number of factors to rotate. The scree plot indicated a break between eight and nine factors, and parallel analysis indicated eight factors with eigenvalues larger than would be expected by chance (p<0.05 with 100 random data sets). We therefore conducted factor analyses with seven, eight, and nine factors to maximize interpretability.

Several factors emerged across algorithms, rotations, and estimation procedures. We report here the most coherent solution, the eight-factor promax (oblique) solution using maximum likelihood estimation, which we favored a priori because of the characteristics of promax rotations (notably the absence of the assumption of orthogonal factors and the tendency to maximize factor loadings within factors) and maximum likelihood estimation (notably the advantages for use in subsequent confirmatory factor analyses). This solution accounted for 69% of the variance and included factors well marked by at least five items each, suggesting a stable factor structure unlikely to be substantially affected by sample size (36).

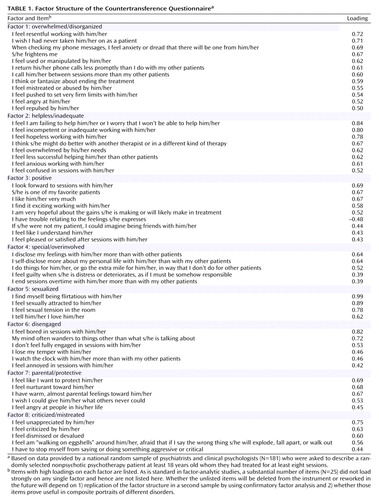

Table 1 presents the factor structure. To create factor-based scores for use in this and subsequent studies, we included items loading ≥0.50 for factors 1 and 2, ≥0.40 for factor 3, and ≥0.375 for factors 4–8 to maximize reliability (coefficient alpha). Intercorrelations among the eight factors ranged from –0.16 to 0.58, with a median of 0.30.

| • | Factor 1, overwhelmed/disorganized (coefficient alpha=0.90), was marked by items indicating a desire to avoid or flee the patient and strong negative feelings, including dread, repulsion, and resentment. The items accord with clinical descriptions of countertransference reactions to patients with axis II cluster B disorders, notably borderline personality disorder and narcissistic personality disorder, and with research on disorganized and unresolved attachment patterns (e.g., references 37, 38). | ||||

| • | Factor 2, helpless/inadequate (coefficient alpha=0.88), included items describing feelings of inadequacy, incompetence, hopelessness, and anxiety. | ||||

| • | Factor 3, positive (coefficient alpha=0.86), was marked by items indicating the experience of a positive working alliance and close connection with the patient. | ||||

| • | Factor 4, special/overinvolved (coefficient alpha=0.75), was marked by items describing a sense of the patient as special, relative to other patients, and by items describing “soft signs” of problems in maintaining boundaries, including self-disclosure, ending sessions on time, and feeling guilty, responsible, or overly concerned about the patient. | ||||

| • | Factor 5, sexualized (coefficient alpha=0.77), included items describing sexual feelings toward the patient or experiences of sexual tension. | ||||

| • | Factor 6, disengaged (coefficient alpha=0.83), included items describing feeling distracted, withdrawn, annoyed, or bored in sessions. | ||||

| • | Factor 7, parental/protective (coefficient alpha=0.80), was marked by items describing a wish to protect and nurture the patient in a parental way, above and beyond normal positive feelings toward the patient. | ||||

| • | Factor 8, criticized/mistreated (coefficient alpha=0.83), included items describing feelings of being unappreciated, dismissed, or devalued by the patient. | ||||

Ruling Out Theoretical Bias as a Rival Hypothesis

This factor structure is conceptually coherent and clinically recognizable. However, an important question is the extent to which its coherence simply reflects the theoretical beliefs of participating clinicians, particularly given that 40% of clinicians in the sample reported a psychodynamic orientation. To evaluate this possibility, we conducted a second factor analysis, this time eliminating all clinicians who reported a psychoanalytic or psychodynamic orientation (remaining N=108). Using the same rotation and estimation procedures, the factor analysis reproduced the same factor structure as in the complete sample, except that the factors appeared in a slightly different order. Thus, the factor structure does not appear to be an artifact of clinicians’ theoretical preconceptions.

Countertransference and Personality Pathology

As a first test of the validity and clinical applicability of the Countertransference Questionnaire, we examined the relationship between each of the eight factors and dimensional measures of the DSM-IV personality disorders. Because of the extensive comorbidity of the axis II disorders, we analyzed the data at the personality disorder cluster level (clusters A, B, and C) by summing the number of symptoms endorsed for each of the personality disorders in each cluster. To control for comorbidity across clusters (and for general severity of personality disturbance), we used partial correlations, controlling for pathology associated with the other two clusters in all analyses.

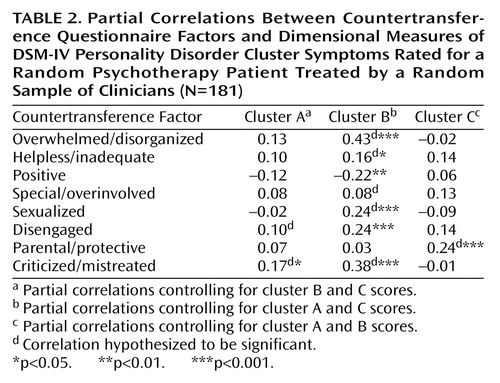

Based on the item content of the factors, we made the following a priori predictions: 1) that the cluster A (odd/eccentric) disorders would be associated with the disengaged factor and secondarily with the criticized/mistreated factor; 2) that the cluster B (dramatic/erratic) disorders would be associated with the overwhelmed/disorganized, helpless/inadequate, special/overinvolved, and sexualized factors; and 3) that the cluster C (anxious) disorders would be associated with the parental/protective factor.

The primary findings are reported in Table 2. As predicted, cluster A showed a significant association with the criticized/mistreated factor, although it was not correlated with the disengaged factor. The data strongly supported the associations for cluster B, except for the special/overinvolved factor. The cluster B (dramatic/erratic) disorders showed an additional (unpredicted) association with the disengaged factor and a negative correlation with positive countertransference. The data supported the hypothesis for cluster C.

In secondary analyses, we followed up on some of these patterns (particularly those that were contrary to our expectations) with hypotheses specific to particular disorders (rather than clusters) using partial correlation analysis, holding constant the other nine disorders in each analysis. We hypothesized that borderline personality disorder would show the expected association with the special/overinvolved factor. This hypothesis was supported (partial r=0.23, df=170, p=0.002). We also hypothesized that narcissistic personality disorder would account for the correlation between cluster B disorders and the disengaged factor. In fact, whereas the other cluster B disorders showed no significant associations with therapist disengagement, narcissistic personality disorder was associated with this factor (partial r=0.30, df=170, p<0.001).

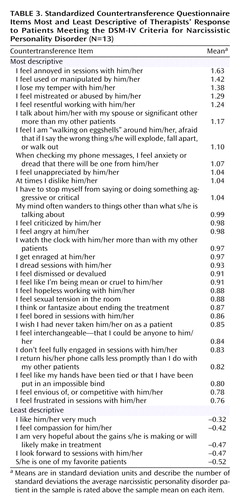

Countertransference Responses to Narcissistic Personality Disorder Patients

To illustrate the uses of the Countertransference Questionnaire in clinical practice and to examine the extent to which it can be used to create empirical prototypes of common countertransference patterns in specific types of pathology, we created a composite description of countertransference patterns in the treatments of patients who met the DSM-IV criteria for narcissistic personality disorder. We standardized (z-scored) the items across patients and then averaged the item scores from patients meeting the DSM-IV criteria for narcissistic personality disorder assessed from the axis II checklist. By standardizing items (setting means to 0) before aggregating, we reduced the salience of items that were descriptive of all patients in the sample (e.g., positive feelings) but not specific to patients with narcissistic personality disorder.

Table 3 presents the items most and least descriptive of therapists’ descriptions of countertransference responses to patients with narcissistic personality disorder (N=13). The composite description is remarkably similar to theoretical and clinical accounts (e.g., references 39–42). Clinicians reported feeling anger, resentment, and dread in working with narcissistic personality disorder patients; feeling devalued and criticized by the patient; and finding themselves distracted, avoidant, and wishing to terminate the treatment.

As with the factor analysis, to see whether this portrait of countertransference responses to narcissistic personality disorder patients could be accounted for by clinicians’ theoretical preconceptions, we created a second composite description excluding the data for the three clinicians reporting a psychoanalytic or psychodynamic orientation (N=10). The items and means were virtually identical, suggesting once again that the data were not theory dependent.

Discussion

The results point to several conclusions. First, we identified eight countertransference dimensions that were robust across extraction methods and rotations: 1) overwhelmed/disorganized, 2) helpless/inadequate, 3) positive, 4) special/overinvolved, 5) sexualized, 6) disengaged, 7) parental/protective, and 8) criticized/mistreated. These dimensions are clinically and theoretically coherent, representing diverse reactions clinicians may have toward patients that likely reflect a combination of the therapist’s own dynamics, responses evoked by the patient, and the interaction of patient and therapist.

The factor structure offers a complex portrait of countertransference processes that is substantially more nuanced than global distinctions between positive and negative countertransference. For example, factor analysis identified an overwhelmed/disorganized pattern of countertransference response, characteristic of clinicians’ response to primarily axis II cluster B patients, which bears substantial similarities to descriptions of disorganized attachment in young children and “unresolved” attachment patterns in adults (37, 38). This factor was distinct from other forms of negative countertransference, notably feeling helpless and inadequate, disengaged, and mistreated by the patient. Similarly, we identified three forms of connection with the patient that have elements of closeness—sexualized, special/overinvolved, and parental/protective—that represent both positive feelings as well as potential countertransference snares. This complexity is consistent with clinical observation. What this study suggests, however, is a way of transcending some of the limitations inherent in clinical theories derived from case studies, in which a single clinician attempts to classify countertransference experiences or constellations based on his or her own experience with a limited number of patients. By using an instrument that provides a “common language” (see reference 43) for describing a subtle clinical phenomenon, we can essentially pool the knowledge of dozens of clinical observers, identifying latent constructs (varieties of countertransference experience) that reflect patterns that individual observers themselves may not have recognized.

Second, although every clinician and every therapeutic dyad is distinct, the significant correlations between the countertransference factors and personality disorder symptoms suggest that countertransference responses occur in coherent and predictable patterns. To put it another way, patients not only elicit idiosyncratic responses from particular clinicians (based on the clinician’s history and the interaction of the patient’s and the clinician’s dynamics) but also elicit what we might call average expectable countertransference responses, which likely resemble responses by other significant people in the patient’s life. The associations between countertransference patterns and personality disorder characteristics support the broad view of countertransference reactions as useful in the diagnostic understanding of the patient’s dynamics, particularly those involving repetitive interpersonal patterns. To the extent that patients sharing diagnostic features on axis II have similar ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving interpersonally, one would expect them to evoke similar reactions from others, including therapists, and this appears to be the case.

Third, data from clinicians of different theoretical orientations showed similar patterns vis-à-vis patients with particular kinds of pathology, suggesting that the results are not artifacts of clinicians’ theoretical preconceptions. What is striking about this finding is that coherent patterns of countertransference response emerge in treatments regardless of whether the clinician even “believes” in the concept of countertransference responses or has been trained to attend to them. Put another way, although the concept of countertransference emerged from psychoanalytic observation, the data suggest that clinicians of all theoretical persuasions should attend to and, where possible, make use of information provided in the context of the therapeutic relationship, including their own responses to the patient.

Finally, the empirical portrait of countertransference responses toward patients with narcissistic personality disorder points to the way researchers can use this measure to create empirical prototypes of subtle countertransference constellations with patients presenting with specific types of personality disturbance. In principle, with a large enough sample, one could empirically map the terrain of countertransference patterns in response to multiple forms of personality pathology. One could also identify distinct constellations within diagnoses (e.g., different kinds of narcissistic patients) or to patients who share certain experiences (e.g., survivors of childhood sexual trauma) that may occur across treatments, at different points in therapy, or at different points in a single therapy hour. In working with survivors of childhood sexual abuse, for example, clinicians often face the opposite danger of pushing too much or too early for the patient to remember—and potentially recapitulating the patient’s subjective experience of unwanted penetration, abuse, or lack of boundaries—versus avoiding discussion of traumatic events in intimate detail for fear of traumatizing the patient—and potentially recapitulating the patient’s experience of unacknowledged but shared secrets or the inability or unwillingness of a caregiver who knew about the abuse to talk about it. Identification of such patterns as common constellations in the treatment of abuse survivors could be very useful in teaching clinicians about potential countertransference dangers inherent in working with abuse survivors in a way that is both clinically sensitive and empirically grounded.

Limitations

This study has three primary limitations. First, although clinicians are the most obvious informants to report on their own countertransference responses, the countertransference measure we used shares the inherent limits of self-report measures, such as defensive biases and failure to recognize processes that an outside observer might identify. Thus, it would have been useful to have ratings of therapy process by an independent observer (perhaps based on audiotaped sessions) to identify patterns of clinicians’ behavior that would likely converge with clinicians’ self-reports in some ways and diverge from them in others.

A related concern is that clinicians provided all the data and hence that their responses on one questionnaire may not be independent of their responses on others (e.g., that their diagnosis of narcissistic personality disorder may not have been independent of their observations of the patient’s behavior in the room with them). This limitation is common to virtually all studies in psychiatry, in which a single observer (usually the patient) provides data on one measure that are then correlated with data from another measure completed by the same informant (either by self-report questionnaire or structured interview). It would have been preferable to collect diagnostic data independently of clinicians’ reports of their countertransference responses, and future research should clearly do so.

Several factors, however, mitigate the concern that the results primarily reflect clinicians’ biases or preconceptions. First, as noted earlier, clinicians of widely different theoretical perspectives and with widely different training (M.D. training versus Ph.D. training) produced highly similar data. If, for example, cognitive behavior clinicians share a theory of countertransference with psychoanalytic therapists, we are unaware of such a theory. Indeed, the similarity across theoretical orientations is one of the most interesting findings of this study, suggesting that patients’ interpersonal patterns are quite robust in the face of different technical styles. Second, because we used dimensional rather than categorical measures of axis II pathology, clinicians’ responses on the countertransference measure were not likely to be influenced by their beliefs about whether the patient had one personality disorder or another. Third, previous research suggests that clinicians tend to make highly reliable and valid judgments if their observations and inferences are quantified using psychometric instruments such as the ones used in this study. For example, correlations between treating clinicians’ and independent interviewers’ assessments of a range of variables, such as measures of personality pathology and adaptive functioning, tend to be large, typically >0.50 (44–46). Empirically, clinicians’ theoretical orientation predicts little variance in descriptions of clinical phenomena when clinicians were asked to describe a specific patient rather than their beliefs or theories of psychopathology (47, 48). Nevertheless, future research using this measure should assess the association between countertransference phenomena and patients’ personality pathology by using data about the patient provided by other observers.

The second limitation was clinicians’ response rate to our request for participation (approximately 10%, for a study described as requiring 3–4 hours of work for a token honorarium). Three factors, however, limit the likelihood that the results reflect response rate biases. First and foremost, it is hard to imagine a response rate hypothesis that could explain the pattern of results. By virtue of their willingness to donate 3–4 hours of their time, the clinicians who participated in the study may have been characterized by greater interest in research, altruism, financial distress, or a host of other factors, compared with colleagues who did not participate, but it is difficult to see how any of these variables could have produced the obtained findings. Second, because we solicited data from clinicians in multiple practice settings across North America and provided them with a method of randomly selecting a patient within their practice, we were able to obtain a broad cross-section of patients. (Clinicians who agreed to participate were unaware that countertransference was one of the constructs we intended to study, so we were not selecting clinicians with a particular interest in or knowledge of this domain.) Third, as noted earlier, psychologists’ response rate was almost three times the rate of psychiatrists, yet the two sets of informants provided similar data, suggesting that neither training nor response rate was responsible for the findings. Finally, all studies have selection biases, some avoidable and others less so. An alternative method would have been to sample clinicians at a single hospital or institution, but this strategy would likely have resulted in less generalizable results. It seems unlikely that the sample in our study was less representative of the population of clinicians or patients in psychotherapy than samples in typical studies of psychotherapy or psychopathology, which tend to rely on patient populations from a single site. Nevertheless, the data clearly require replication and extension with new groups of patients, and we hope this article will generate interest in the measure for future research.

A third potential objection is sample size, given the possibility of some instability of factor structure with a ratio of cases to items of <3:1. However, recent thinking about factor analysis, based on data from Monte Carlo simulations and other studies, suggests that factor solutions stabilize with far fewer cases than previously believed (typically by 100 cases), as long as the factors are well marked by a sufficient number of items with loadings above 0.40 or 0.50 (as they were here), and that conventional case-to-item ratios do not take into consideration a range of variables that qualifies them in one direction or the other (see, e.g., references 36, 49). Clearly the next step in this research, however, is a larger-N replication study using confirmatory factor analysis and external ratings of variables such as personality disorder diagnosis and treatment outcome independent of the clinician’s reports.

Implications

The Countertransference Questionnaire represents an effort to develop a readily administered measure that reflects shared clinical wisdom in its item content and statistical “wisdom” in its factor structure. This measure is germane to future research on countertransference phenomena, as well as to practice, allowing clinicians to clarify the diagnostic relevance and utility of their reactions by comparing their own responses to normed psychometric data. A broadband measure of countertransference processes with known correlates such as this can turn clinicians’ experiences into quantifiable dimensions that capture interpersonal patterns that emerge in sessions, allowing clinicians who normally attend to countertransference phenomena to hone and systematize their self-reflections and providing clinicians whose theoretical orientations do not emphasize such processes a language and method with which to capture information about the patient and the treatment process that may be diagnostically and therapeutically significant.

|

|

|

Received March 17, 2004; revision received July 13, 2004; accepted Aug. 18, 2004. From Georgia School of Professional Psychology; Emory University Psychoanalytic Institute, Atlanta; Hoover & Associates, Orland Park, Ill.; Cambridge Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, Mass.; Harvard Medical School, Boston; and the Departments of Psychology and Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Emory University. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Betan, Georgia School of Professional Psychology, 980 Hammond Dr., Suite 100, Atlanta, GA 30328; [email protected] (e-mail); or Dr. Westen, Departments of Psychology and Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Emory University, 532 Kilgo Circle, Atlanta, GA 30322; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-62377 and MH-62378 to Dr. Westen and by a grant from the Fund for Psychoanalytic Research of the American Psychoanalytic Association to Dr. Heim.The authors thank the 181 clinicians who contributed data to this study.

1. Heimann P: On countertransference. Int J Psychoanal 1950; 31:81–84Google Scholar

2. Kernberg O: Notes on countertransference. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 1965; 13:38–56Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Racker E: The meanings and use of countertransference. Psychoanal Q 1957; 26:303–357Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Sandler J: Basic psychoanalytic concepts, IV: counter-transference. Br J Psychiatry 1970; 117:83–88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Winnicott D: Hate in the countertransference. Int J Psychoanal 1949; 30:69–75Google Scholar

6. Klein M: Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. Int J Psychoanal 1946; 27:99–110Medline, Google Scholar

7. Bion W: Learning From Experience. London, Heinemann, 1962Google Scholar

8. Gabbard G: A contemporary psychoanalytic model of countertransference. J Clin Psychol 2001; 57:983–991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Ogden TH: Projective Identification and Psychotherapeutic Technique. New York, Jason Aronson, 1982Google Scholar

10. Sandler J: Countertransference and role-responsiveness. Int Rev Psychoanal 1976; 3:43–47Google Scholar

11. Wachtel P: Psychoanalysis and Behavior Therapy. New York, Basic Books, 1977Google Scholar

12. Wachtel PL: Resistance as a problem for practice and theory. J Psychotherapy Integration 1999; 9:103–117Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Brody F, Farber B: The effects of therapist experience and patient diagnosis on countertransference. Psychotherapy 1996; 33:372–380Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Colson DB, Allen J, Coyne L, Dexter N, Jehl N, Mayer CA, Spohn H: An anatomy of countertransference: staff reactions to difficult psychiatric patients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1986; 37:923–928Abstract, Google Scholar

15. Holmqvist R, Armelius B: The patient’s contribution to the therapist’s countertransference feelings. J Nerv Ment Dis 1996; 184:660–666Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. McIntyre S, Schwartz R: Therapists’ differential countertransference reactions toward clients with major depression or borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychol 1998; 54:923–931Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Dube J, Normandin L: The mental activities of trainee therapists of children and adolescents: the impact of personal psychotherapy on the listening process. Psychotherapy 1999; 33:216–228Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Swann WB: The trouble with change: self-verification and allegiance to the self. Psychol Sci 1997; 8:177–180Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Downey G, Freitas AL, Michaelis B, Khouri H: The self-fulfilling prophecy in close relationships: rejection sensitivity and rejection by romantic partners. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998; 75:545–560Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Giesler R, Josephs RA, Swann WB: Self-verification in clinical depression: the desire for negative evaluation. J Abnorm Psychol 1996; 105:358–368Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Hayes JA, Gelso CJ: Effects of therapist-trainees’ anxiety and empathy on countertransference behavior. J Clin Psychol 1991; 47:284–290Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Hayes JA, Gelso CJ: Male counselors’ discomfort with gay and HIV-infected clients. J Couns Psychol 1993; 40:86–93Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Rosenberger EW, Hayes JA: Origins, consequences, and management of countertransference: a case study. J Couns Psychol 2002; 49:221–232Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Sharkin BS, Gelso CJ: The influence of counselor trainee anger-proneness and anger discomfort on reactions to an angry client. J Couns Dev 1993; 71:483–487Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Yulis S, Kiesler DJ: Countertransference response as a function of therapist anxiety and content of patient talk. J Consult Clin Psychol 1968; 32:413–419Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Robbins SB, Jolkovski MP: Managing countertransference feelings: an interactional model using awareness of feeling and theoretical framework. J Couns Psychol 1987; 34:276–282Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Najavits LM, Griffin ML, Luborsky L, Frank A, Weiss RD, Liese BL, Thompson H, Nakayama E, Siqueland L, Daley D, Onken LS: Therapists’ emotional reactions to substance abusers: a new questionnaire and initial findings. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice 1995; 32:669–677Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Westen D, Shedler J: Revising and assessing axis II, part I: developing a clinically and empirically valid assessment method. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:258–272Abstract, Google Scholar

29. Westen D, Shedler J, Durrett C, Glass S, Martens A: Personality diagnoses in adolescence: DSM-IV axis II diagnoses and an empirically derived alternative. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:952–966Link, Google Scholar

30. Blais M, Norman D: A psychometric evaluation of the DSM-IV personality disorder criteria. J Personal Disord 1997; 11:168–176Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Morey LC: The Personality Assessment Inventory: Professional Manual. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1991Google Scholar

32. Zittel C, Westen D: The Countertransference Questionnaire. Atlanta, Emory University, Departments of Psychology and Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 2003. http://www.psychsystems.net/labGoogle Scholar

33. Horn JL: An empirical comparison of methods for estimating factor scores. Educational and Psychological Measurement 1965; 25:313–322Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Horn JL: A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika 1965; 30:179–185Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. O’Connor BP: SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer’s MAP test. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 2000; 32:396–402Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Fabregar LR, Wegener DT, MacCallum RC, Strahan EJ: Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol Methods 1999; 4:272–299Crossref, Google Scholar

37. Cassidy J, Mohr JJ: Unsolvable fear, trauma, and psychopathology: theory, research, and clinical considerations related to disorganized attachment across the life span. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 2002; 8:275–298Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J: Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: a move to the level of representation. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 1985; 50:66–104Crossref, Google Scholar

39. Altshul VA: The so-called boring client. Am J Psychother 1977; 31:533–545Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Blieberg E: Stages in the treatment of narcissistic children and adolescents. Bull Menninger Clin 1987; 51:296–313Medline, Google Scholar

41. Kernberg O: Further contributions to the treatment of narcissistic personalities. Int J Psychoanal 1974; 55:215–240Medline, Google Scholar

42. Segel NP: Narcissism and adaptation to indignity. Int J Psychoanal 1981; 62:465–476Medline, Google Scholar

43. Block J: The Q-Sort Method in Personality Assessment and Psychiatric Research. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1978Google Scholar

44. Hilsenroth MJ, Ackerman SJ, Blagys MD, Baumann BD, Baity MR, Smith SR, Price JL, Smith CL, Heindselman TL, Mount MK, Holdwick DJ Jr: Reliability and validity of DSM-IV axis V. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1858–1863Link, Google Scholar

45. Westen D, Muderrisoglu S, Fowler C, Shedler J, Koren D: Affect regulation and affective experience: individual differences, group differences, and measurement using a Q-sort procedure. J Consult Clin Psychol 1997; 65:429–439Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Westen D, Muderrisoglu S: Reliability and validity of personality disorder assessment using a systematic clinical interview: evaluating an alternative to structured interviews. J Personal Disord 2003; 17:350–368Crossref, Google Scholar

47. Shedler J, Westen D: Refining the measurement of axis II: a Q-sort procedure for assessing personality pathology. Assessment 1998; 5:333–353Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Shedler J, Westen D: Dimensions of personality pathology: an alternative to the five-factor model. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1743–1754Link, Google Scholar

49. Russell DW: In search of underlying dimensions: the use (and abuse) of factor analysis in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. Pers Social Psychol Bull 2002; 28:1629–1646Crossref, Google Scholar