Attachment Disorders in Infancy and Early Childhood: A Preliminary Investigation of Diagnostic Criteria

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The primary purpose of this study was to compare the reliability of differing sets of criteria for attachment disorders by using a retrospective case review. METHOD: Forty-eight consecutive clinical case summaries from an infant behavior clinic were reviewed by four experienced clinicians. Attachment disorders were coded as present or absent by using competing criteria and were scored by using a continuous scale of relationship functioning. RESULTS: The reliability of alternative criteria was acceptable, but the reliability of DSM-IV criteria in diagnosing attachment disorders was marginal. Preliminary validity for the criteria was demonstrated by the fact that more severe relationship disturbances were seen in infants diagnosed with attachment disorders than in infants diagnosed with other disorders. CONCLUSIONS: Standardized assessments of at-risk populations should be used to replicate these preliminary results; revision of DSM-IV criteria may be necessary to obtain adequate reliability for diagnosing attachment disorders. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:295–297)

Reactive attachment disorder was first introduced in DSM-III, although the criteria for reactive attachment disorder have been substantially revised since that time (1). It is one of the few diagnoses in the standard nosologies that are applicable to children under 3.

DSM-IV criteria maintain a distinction between two basic types of reactive attachment disorder: 1) inhibited, in which the child is generally withdrawn and hypervigilant and seeks proximity to potential caregivers in ambivalent or odd ways, and 2) indiscriminate, in which the child seeks proximity and contact with any available caregiver, a symptom complex known as indiscriminate sociability (2).

DSM-IV criteria have been criticized for focusing broadly on social abnormalities rather than attachment, for including “pathogenic” parental care in the criteria, for requiring cross-contextual consistency in symptom pictures, and for representing maltreatment syndromes rather than attachment disorders (1, 3). These problems led to using findings from developmental research on attachment as a nexus for a set of alternative criteria (4).

Difficulty in applying DSM criteria, coupled with little research on clinical disorders in infancy (3, 5), may account for the fact that, despite hundreds of studies of patterns of attachment from developmental research in the past 15 years, there has not been one study that has used a group of subjects to investigate the reliability and validity of clinical disorders of attachment.

This study was designed to address three aspects of reliability and validity of criteria for attachment disorders in children. First, we had clinician raters review case charts to test and compare the reliability of the differing sets of criteria. Second, to examine external validity of the criteria in a preliminary way, we hypothesized that infants with attachment disorders would have more compromised relationship functioning with their primary caregivers than infants with other types of clinical disorders. Third, we analyzed clinical and demographic variables that might be related to the development of attachment disorders.

METHOD

This study was designed as a retrospective chart review that used 48 consecutive clinical case summaries from an infant psychiatry clinic. The clinic surveyed was a primary referral source for the state child protective services (accounting for 79% of cases in this study); the remainder of cases had been referred by private pediatricians or community clinics or had been self-referred. The clinic did not focus on developmental disabilities, and less than 10% were identified as being significantly developmentally delayed. The age range was 9–36 months (mean age=24 months); a wide range of socioeconomic status strata was represented. Infant diagnoses other than attachment disorders included disorders of sleep (31%, N=15) and feeding (including failure-to-thrive [17%, N=8]), disruptive behavior disorders (50%, N=24), and language and other developmental disorders (17%, N=8). Posttraumatic stress disorders and parent-child problems were less commonly diagnosed; only 10% (N=5) had no psychiatric disorder.

Four clinicians, experienced in the clinical evaluation of infants but not specially trained for this study, were given copies of the written evaluations from the clinic charts. The criteria from DSM-IV and the alternative criteria were converted into brief paragraph descriptors consistent with the format of ICD-10; this afforded the clinician raters maximum flexibility in deciding whether criteria were met (6).

A global rating scale of the relationship between the primary caregiver and the infant, the Parent-Infant Relationship Global Assessment Scale (7), provided a continuous measure of the adaptive status of the relationship. This scale measures overall relationship functioning, without regard to whether relationship impairments arise from the infant, the caregiver, or the unique fit between the two. While its psychometric properties have not been established in a large sample, other similar global assessment scales have proven to have adequate interrater reliability (8).

RESULTS

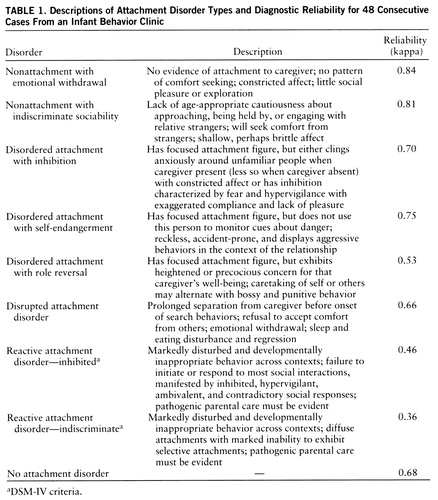

To assess the interrater reliability of the four raters who coded each case independently, Cohen's kappa between pairs of raters was computed for the presence or absence of each type of attachment disorder across all cases. These pairwise kappas ranged from 0.48 to 0.88, with an overall mean of 0.64. There were substantial differences in the pooled mean kappas that depended upon the attachment disorder criteria used, as shown in table 1. Ratings that used alternative criteria (3) for attachment disorders with inhibition or indiscriminate sociability had more agreement than did the corresponding DSM-IV criteria. The additional categories also attained acceptable levels of interrater agreement, with the exception of attachment disorder with role reversal. In all, 20 of the 48 subjects (42%) were deemed to meet criteria for one or more subtypes of attachment disorders according to at least three of the four raters. The mean kappa for “no attachment disorder” (0.68) reflects agreement on which children did not meet full criteria for one of the eight attachment disorder types.

A 2 (group) by 4 (raters) repeated measures analysis of variance was performed with scores on the Parent-Infant Relationship Global Assessment Scale as the dependent variable. Parent-Infant Relationship Global Assessment Scale ratings were significantly lower for infants diagnosed with an attachment disorder (F=58.41, df=1,46, p<0.001, power of 1), which suggests greater disturbances in relationships for this subgroup. Although the within-group analysis indicated that the raters differed in their use of the scale (F=6.49, df=3,44, p<0.001), the intraclass correlation (8) revealed a very high degree of agreement overall (0.96). The mean Parent-Infant Relationship Global Assessment Scale score for the infants who met criteria for an attachment disorder (according to at least three raters) was 21 (which corresponds to a rating of “severely disordered”). The mean Parent-Infant Relationship Global Assessment Scale score for infants who did not meet attachment disorder criteria was 47 (which corresponds to a rating of “distressed”).

A forward logistic regression was performed to investigate whether specific demographic or historical variables were related to the presence or absence of an attachment disorder. Gender, current medical status (compromised in seven subjects), history of significant medical illness (15 subjects), history of maltreatment (documented in nine subjects), intactness of the family (26 cases were single caregiver families), number of placements, and total problem behavior score (e.g., excessive crying, disturbed sleep or eating patterns, or general behavior problems) were entered in a stepwise logistic regression. Only one variable (intactness of the family) was a significant predictor of attachment disorder status. The model created with this variable had a 69% hit rate. In the goodness-of-fit chi-square (testing whether this model differed significantly from a perfect model), this model's significance level was moderate (χ2=48, df=46, p=0.39), and the model's improvement over chance was significant (χ2=6.66, df=1, p<0.01).

The age range in this study (9–36 months) represents a broad developmental range. It is expected that the behaviors consistent with any disorder in this age range may vary with the child's developmental stage (5). The following case summaries are provided as examples of infants and young children who met criteria for an attachment disorder according to at least three of the four raters.

Case 1. Andrew, a white, 12-month-old boy, was referred to the clinic after admission to a local hospital for failure to thrive. He was the product of an unwanted pregnancy of a 29-year-old single mother of five. Andrew was described by his mother as a “happy and pleasant baby.” His birth weight was 2.7 kg, and when he was admitted just before his first birthday he weighed 3.7 kg (he placed well below the fifth percentile in weight, height, and head circumference). In the hospital, Andrew was irritable and wary in the presence of his mother and showed no preference for her over various nursing staff. He rarely actively sought comfort when distressed and did not engage easily with others. Feeding interactions were marked by gaze aversion. Andrew was minimally responsive to his mother, despite her intermittently sensitive and responsive cues while being observed. Cognitive delays were only mild, and he appeared to have the capacity for social engagement. Home visits revealed that the family was living in “deplorable” physical conditions.

Case 2. Julie, a 35-month-old mixed-race child, was referred by Child Protective Services and her pediatrician for evaluation. She had been placed in foster care 5 months before referral because her mother was known to have a “drinking problem” and her father was in prison. She had reportedly witnessed violence between her parents before placement, although her biological mother denied this. Her foster mother reported that Julie was preoccupied with being separated from her foster parents and frequently insisted on sleeping in their room. However, she would also often approach and seek closeness from adult strangers at the playground and would refuse to be separated from babysitters that she had just met. At her initial evaluation, Julie displayed overly bright affect, engaged quickly with the examiner, and then sat in his lap and asked whether he would “like a little girl like her.”

DISCUSSION

This investigation is the first to examine the reliability and validity of diagnostic criteria for attachment disorders in children less than 3 years old. A significant proportion of this population met criteria for one or more attachment disorders. The most important finding of the investigation was that alternative criteria for inhibited and indiscriminate types of attachment disorder were rated with acceptable levels of interrater agreement but DSM-IV criteria for the same types were not. Several other proposed types of attachment disorders had acceptable levels of interrater reliability.

Although validity criteria have yet to be established for attachment disorders, this study demonstrated that infants diagnosed with attachment disorders had lower levels of relationship functioning than infants diagnosed with other clinical disorders. Attempting more complete validation of disorders of attachment is clearly an important effort for future research, given that there is general consensus that these disorders describe symptom pictures that are not captured by other disorders (3) and given the strong links between attachment classifications and other clinical disorders (9). It is clear that attachment disorders may be reliably diagnosed without clear evidence of “pathogenic” parental care, and this requirement should be removed from future DSM revisions. These results also suggest that other subtypes of attachment disorder (e.g., self-endangering, attached but inhibited, and role-reversed) may exist, but further study of these criteria is necessary.

These data, derived from chart reviews, must be considered preliminary. The results need replication in a study in which all of the criteria used to diagnose attachment disorders are systematically assessed. Development of standardized approaches to assessment stands as a challenge for research in this area (10).

|

Received Sept. 3, 1996; revisions received April 24 and July 21, 1997; accepted Sept. 4, 1997. From the Infant Development Center. Address reprint requests to Dr. Boris, Infant Development Center, 111 Plain St., Providence, RI 02903. S upported by NIMH Physician/Scientist Career Development Awar d MH-00999 and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (Dr. Boris).

1. Zeanah CH: Beyond insecurity: a reconceptualization of clinical disorders of attachment. J Consult Clin Psychiatry 1996; 64:42–52Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Richters MM, Volkmar FR: Reactive attachment disorder of infancy or early childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:328–332Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Lieberman A, Zeanah CH: Disorders of attachment in infancy, in Infant Psychiatry: Child Psychiatric Clinics of North America. Edited by Minde K. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1995, pp 571–588Google Scholar

4. Zeanah CH, Boris NW, Scheeringa MS: Psychopathology in infancy. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1997; 38:81–99Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Volkmar F: Reactive attachment disorder, in DSM-IV Sourcebook, vol 5. Edited by Widiger TA, Frances AJ, Pincus HA, Ross R, First MB, Davis WW. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press (in press)Google Scholar

6. Zero to Three: Diagnostic Classification:0–3. Arlington, Va, Zero to Three, 1994Google Scholar

7. Green B, Shirk S, Hanze D, Wanstrath J: The Children's Global Assessment Scale in clinical practice: an empirical evaluation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:1158–1164Google Scholar

8. Shrout PE, Fleiss JL: Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979; 86:420–428Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Speltz ML, Greenberg MT, DeKlyen M: Attachment in preschoolers with disruptive behavior: a comparison of clinic-referred and nonproblem children. Dev Psychopathol 1990; 2:31–46Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Boris NW, Fueyo M, Zeanah CH: The clinical assessment of attachment in children under five. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:291–293Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar