Patterns and Predictors of Treatment Contact After First Onset of Psychiatric Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors used self-report data to study patterns and predictors of treatment contact after the first onset of DSM-III-R mood, anxiety, and addictive disorders. METHOD: Data from the National Comorbidity Survey, a general population survey of 8,098 respondents, were used. Disorders were assessed by using a modified version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Age at onset and age at first treatment contact were assessed retrospectively. RESULTS: There was great variation across disorders in lifetime probability of treatment contact. Most treatment contact was delayed; the median delay time was between 6 and 14 years across the disorders considered here. Probability of treatment contact was inversely related to age at onset and increased in younger cohorts. The effects of sociodemographic variables were modest and inconsistent across disorders. CONCLUSIONS: The majority of people with the disorders considered here eventually make treatment contact. However, delay was pervasive. Further research is needed on the determinants of delay and on the low probability of lifetime treatment contact among people with early-onset psychiatric disorders. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:62–69)

Only a minority of adults with psychiatric disorders receive professional treatment during a year (1, 2), even among those who report substantial distress and role impairment (3, 4). This widespread unmet need at a time when clinical advances have made it possible to provide effective treatments for many psychiatric disorders underscores the importance of public health efforts to narrow the gap in service delivery (5–7).

Much of the extant research on determinants of help-seeking for psychiatric problems has concentrated on individual differences in clinical (8–10), demographic (11–14), economic (15–17), attitudinal (18), cultural (19, 20), social (21–23), and geographic (24, 25) factors and has focused on service use among prevalent cases over relatively short time periods (typically 1 year or less). Considerably less is known about the speed of treatment contact among incident cases over longer time periods, with the exception of research on the treatment lag following first episodes of schizophrenia (26–28). What little we do know about speed of initial treatment contact, furthermore, is based on retrospective studies of clinical rather than general population samples (29–31).

The current report presents data on initial treatment contact after first onset of specific psychiatric disorders from the National Comorbidity Survey (1). We consider four issues. First, we examine the temporal distributions and cumulative probabilities of treatment contact for each of five disorder types: mood disorders (major depression or dysthymia), panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, phobia (simple, social, or agoraphobia with or without panic), and addictive disorders (alcohol or drug abuse or dependence). Our initial hypothesis was that treatment contact would be highest for panic disorder because of its dramatic onset and high impairment and lowest for phobia and addictive disorders because of the comparatively low impairment of phobia and the reluctance of addicts to quit.

Second, we evaluate within disorders whether probability and speed of initial treatment contact are associated with age at onset. A plausible case could be made for either a positive or a negative effect of age at onset. The fact that early onset is associated with greater risk of persistence and of impairment in some disorders (32–34) suggests that individuals with early-onset disorders might have a particularly high probability of treatment contact. However, it might also be that early-onset disorders are less likely to be recognized as problems requiring treatment than later-onset disorders.

Third, we evaluate whether there are significant differences among cohorts in treatment contact. We hypothesized that treatment contact would be more common in younger cohorts due to a combination of increased public education, advances in treatment, and increased public acceptance of mental health treatment.

Fourth, we evaluate whether there are significant sociodemographic differences in probability and speed of treatment contact. Consistent with previous research, we hypothesized that treatment contact would be more likely among women than men (13, 35), among whites than nonwhites (11, 12), among the married than the unmarried (13, 14), among the well educated than the poorly educated (13, 19), and among urban than rural residents (25).

METHOD

Sample

The National Comorbidity Survey is based on a national probability sample of individuals 15 to 54 years of age in the noninstitutionalized civilian population. Fieldwork was carried out between September 1990 and February 1992. The response rate was 82.4%. A total of 8,098 interviews were completed. Verbal informed consent was obtained before beginning the interviews from respondents 18 years old or older and from not only respondents 15–17 years old but also their parents. The data were weighted for differential probabilities of selection and nonresponse. A weight was also included to adjust the sample to approximate the cross-classification of the population distribution on a range of sociodemographic characteristics. These weights are described in more detail elsewhere (1, 36).

Diagnostic Assessment

The psychiatric diagnoses considered here consist of DSM-III-R major depressive episode and dysthymia, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, phobia (either simple, social, or agoraphobia with or without panic), and addictive disorders (alcohol or drug abuse or dependence). These diagnoses were generated from a modified version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (37), a structured interview designed to be used by trained interviewers who are not clinicians. WHO field trials (38) and National Comorbidity Survey clinical reappraisal studies (39–42) documented acceptable reliability and validity of all these diagnoses.

Treatment Contact

At the end of the diagnostic sections for each of the five types of disorders, National Comorbidity Survey respondents were asked whether they ever told a medical doctor other than a psychiatrist (defined as an M.D., D.O., or a student in training to become an M.D. or D.O.), a mental health specialist (defined as a psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker), or any other professional (defined as a nurse, minister, priest, rabbi, or counselor) about the problems discussed in that section of the interview. Positive responses were followed with probes for the ages when the respondent first told each type of professional. These responses were combined for purposes of the present report to code the earliest age the respondent reported telling any of the three types of professional about the disorder.

It is important to recognize that the focus is on when respondents first “told” a professional, not when they first sought treatment or first received treatment. Telling a professional is only an initial stage in the process that ultimately results in receiving treatment. It is noteworthy that when we pool across diagnoses, 67.8% (N=1,816) of the respondents who reported ever “telling” a professional about their psychiatric problems at a given age also reported in another part of the interview that they “went to see a professional about” these problems as of that same age. The proportion increases to more than 82% (N=2,216) if we include people who subsequently “went to see a professional about” psychiatric problems at some later time in their life. Although the National Comorbidity Survey does not include information on the kind of treatment provided, we do know that close to 90% of the people who “went to see a professional about” psychiatric problems in the year before the interview reported more than one visit. These results suggest that the outcome variable in the current report, telling a professional, is an important early step in the help-seeking process that usually results in subsequent treatment.

Predictor Variables

Three time-related variables were considered as predictors of treatment contact. The first is retrospectively reported age at onset, coded as a series of categories (age 0–12, 13–19, 20–29, or ≥30). The second is time since onset of disorder, a variable created by subtracting age at onset from age in a given year of observation and coded as a series of categories (age at onset and 1–4, 5–9, 10–19, or ≥20 years since onset). The third variable is cohort, which is indexed by the respondent's age at interview and coded as a series of categories (born in 1936–1945, 1946–1955, 1956–1965, or 1966–1975). Six sociodemographic characteristics were also included as predictors: sex (male or female), race (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other), geographical region (Northeast, Midwest, West, or South), marital status (never married, previously married, or currently married), education (current high school student; current college, graduate school, or professional student; or nonstudent with <12, 12, 13–15, or ≥16 years of education), and urbanicity (metropolitan or other urban area or rural area).

Analysis Procedures

The Kaplan-Meier method (43) was used to generate a speed-of-contact curve for each disorder. Discrete-time survival analysis (44) was used to study the predictors of speed of contact within and across disorders. Age at onset, sex, and race were treated as time-invariant predictors, and number of years since onset, education, marital status, and urbanicity were treated as time-varying covariates. Time-varying values of education were assigned by assuming that all respondents entered first grade at age 6 and continued through the end of their schooling without interruption. Time-varying values of marital status were assigned from respondent-reported marital event histories. Time-varying values of urbanicity were assigned by assuming that respondent-reported childhood urbanicity applied up through the age of completing school and that urbanicity at the time of interview applied thereafter. Standard errors of parameter estimates in the survival models were estimated by using the method of jackknife repeated replications (45). An SAS macro (46) was written to operationalize the jackknife repeated replications procedure.

RESULTS

Cumulative Lifetime Probability of Treatment Contact

Figure 1 shows disorder-specific Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative probability of treatment contact for each disorder. The vast majority of people with major depression/dysthymia, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder are estimated eventually to make treatment contact for these disorders, while about half the people with phobia and addictive disorders are estimated to make treatment contact eventually. It is important to note that these projected lifetime probability estimates are considerably higher than the proportions of subjects who reported lifetime treatment for these disorders at the time of interview (73.2% for panic disorder, 70.8% for generalized anxiety disorder, 56.2% for major depression/dysthymia, 30.9% for addictive disorders, and 30.8% for phobia). This difference is the familiar one between lifetime risk and lifetime-to-date prevalence. A consistent finding across disorders in the figure is that the probability of initial treatment contact is considerably higher in the year of onset than subsequent years (χ2=287.6–891.6, df=1, p<0.001). In addition, the incremental increase in probability of contact is fairly constant after the first year for all disorders.

Four additional between-disorder results are also noteworthy. First, there is substantial variation in probability of treatment contact in the year of onset, ranging from a high of greater than 50% for panic disorder to a low of about 10% for phobia and addictive disorders (χ2=343.7, df=4, p<0.001). Second, variation in conditional probabilities in subsequent years is much smaller, although still statistically significant (χ2=145.0, df=4, p<0.001), ranging from a yearly high of 5.9% for generalized anxiety disorder to a low of 1.4% for phobia. Third, with the exception of panic disorder, only a minority of the people who eventually made treatment contact for these disorders—approximately one-third of those with phobia and addictive disorders and one-half of those with major depression/dysthymia and generalized anxiety disorder—did so in the year of onset. In comparison, approximately 70% of those who eventually made treatment contact for panic disorder did so in the year of onset. Fourth, the average delay among those who did not make treatment contact in the year of onset is quite long, ranging from 6 years for major depression/dysthymia to 14 years for generalized anxiety disorder.

The Effects of Age at Onset, Time Since Onset, and Cohort

A series of survival models was estimated to evaluate the separate and joint effects of age at onset, time since onset, cohort (year of birth), and their interactions in predicting initial treatment contact. Model comparisons based on an evaluation of difference in likelihood-ratio chi-squares showed that none of the interactions was significant, that the main effect of age at onset was consistently significant, and that the effects of time since onset and cohort were significant for some, but not all, outcomes. (Detailed results of model-fitting and other results described in the text are available in a technical appendix that can be obtained either from Dr. Kessler or from the National Comorbidity Survey World Wide Web home page described in the Acknowledgements.)

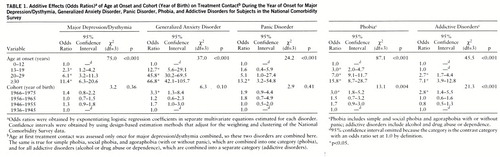

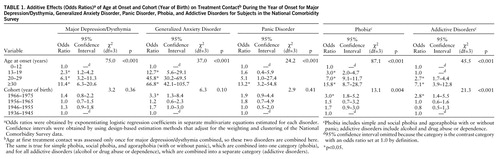

The effects of age at onset and cohort (year of birth) on treatment contact in the year of disorder onset are reported in table 1. Coefficients are odds ratios obtained by exponentiating survival coefficients. A powerful inverse effect of age at onset can be seen across all disorders such that the younger the person, the higher the probability that he or she would make treatment contact. There are also significantly higher rates of treatment contact in the most recently born cohort than in older cohorts for all disorders other than major depression/dysthymia and significant overall cohort effects for phobia and addictive disorders.

The effects of age at onset, time since onset, and cohort (year of birth) on initial treatment contact in subsequent years are reported in table 2. A significant inverse effect of age at onset can be seen for all disorders except panic disorder. A significant effect of time since onset can be seen for all disorders other than panic disorder, although the shape of this effect differs greatly across disorders. A higher relative odds of treatment contact in younger than in older cohorts can be seen for all disorders, although this effect is statistically significant only for major depression/dysthymia and phobia.

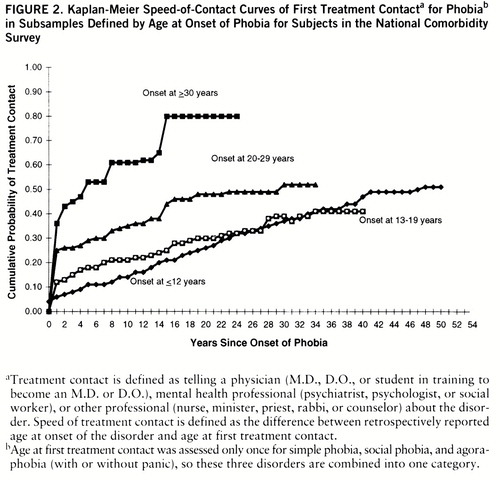

The substantive magnitude of the joint effects of age at onset and time since onset is illustrated for first treatment contact for phobia in figure 2. Cumulative probabilities of treatment contact are approximately twice as high among respondents with onsets at ages 30 and older as among those with onsets at ages 0 to 19 across the entire time-since-onset range. Similar patterns exist for the other disorders. (Results not presented.)

The Effects of Sociodemographic Predictors

We estimated a series of more elaborate survival models to evaluate the effects of sociodemographic predictors after controlling for the significant effects of age at onset, time since onset, and cohort. However, no more significant effects were found than would be expected by chance.

DISCUSSION

There are several methodological limitations of the current report. The measure of treatment contact is less precise than we would like it to be in that it is based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview question about “telling” a physician rather than on more detailed probing about the nature of the initial encounter between patient and professional. We have no way of knowing from this question whether initial contact occurred as part of a physician visit or as part of an informal interaction. Nor do we have any way of knowing whether telling a physician occurred as part of an active help-seeking visit for the psychiatric problem or in response to a physician's question during a visit for some other problem. Analysis of this outcome is nonetheless interesting because telling a professional is a necessary initial step in a help-seeking process that often results in eventual treatment.

The long and uncertain period of recall associated with dating the onset of disorder and initial treatment is an additional limitation. Recall bias could distort results because of the retrospective nature of the data. In addition, a great many different statistical tests were performed on the data without correction for multiple comparisons. This means that some of the results found to be significant could be due to chance. These results should consequently be interpreted with caution and considered tentative until replicated in an independent dataset.

Within the context of these limitations, the results suggest that most individuals with depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder and approximately half of those with phobia and addictive disorders eventually make professional treatment contacts for these disorders. However, there is usually a delay averaging between 6 and 14 years across these disorders. Delay in receiving treatment after making the initial contact presumably also exists. Probability of treatment contact appears to have increased in younger cohorts. However, the consistently strong inverse relationship between age at onset of the disorder and probability of treatment contact exists equally across all cohorts.

The variation found across disorders in probability of treatment contact is generally consistent with our hypothesis that panic disorder would have the highest rate and that phobia and addictive disorders would have the lowest rates. We were surprised, however, that the lifetime probability of treatment contact for generalized anxiety disorder and for depression was similar to that for panic disorder. We were also surprised that more than 80% of the subjects with these disorders eventually made treatment contact. We do not know how many of these people subsequently received treatment, but we do know that they told a professional about their disorder. This lifetime perspective places in broader context the widely cited finding that most individuals with a mental disorder do not receive treatment during the course of a year (1, 2) and highlights the importance of improving our understanding of the complex processes involved in delay in treatment contact and in professional response to patients' reports of illness.

Delays and low overall probabilities of lifetime treatment contact were found to be especially likely among people with childhood-onset mood and anxiety disorders. This is very important in the light of the fact that these early-onset disorders tend to be more severe and disabling than later-onset disorders (32–34). Delays in reporting childhood-onset disorders presumably occur because children are dependent on the adults around them to initiate the referral process (47, 48). Children who develop mental disorders that do not involve disruptive behaviors are unlikely to generate the level of adult concern necessary to initiate a mental health referral, which presumably helps explain our finding that early-onset addictive disorders have a much higher relative odds of rapid treatment contact than the other disorders considered here.

It is less clear why persons with early-onset disorders continue to have low rates of initial treatment contact even after they enter adulthood. Our speculation is that people who have been worried, fearful, or depressed for as long as they can remember might be less likely than those with a later onset to consider their symptoms “abnormal,” a deviation from their own expected standard of functioning. This substantially lower probability of treatment contact for early-onset disorders is a matter of concern that warrants closer study.

On a more positive side, we found higher rates of treatment contact in younger cohorts. This presumably reflects the joint effects of the changing attitudes toward mental illness (49) and the expansion of mental health insurance (50), both of which are known to affect help-seeking patterns (15, 51).

The cohort effect varies across disorders and is most clearly evident for depressive disorders and phobia. Extensive public education programs focused on depression (6), together with advances in the efficacy and safety of the treatment of depression and phobia (52–55), may have contributed to the greater increase in treatment contacts for these than for the other disorders considered here.

At the other extreme, no significant cohort effect was observed for either panic or addictive disorders. In the case of panic disorder, probability of treatment contact is very high across all cohorts, presumably due to the prominent symptoms that herald the onset of panic disorder and lead to a primary care evaluation (56, 57). In contrast, the absence of a cohort effect for addictive disorders was found in the context of consistently low rates of treatment contact. It is likely that public intolerance, insurance policies that restrict addiction treatment services, and the addicted individual's reluctance to seek help are all involved in sustaining this pattern. Given the enormous economic, health, and functioning burdens of addictive disorders, this low level of treatment contact is a problem that warrants increased attention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The National Comorbidity Survey is a collaborative epidemiologic investigation of the prevalence, causes, and consequences of psychiatric morbidity and comorbidity in the United States. Collaborating National Comorbidity Survey sites and investigators are the Addiction Research Foundation (Robin Room), Duke University Medical Center (Dan Blazer, Marvin Swartz), Harvard Medical School (Richard Frank, Ronald Kessler), Johns Hopkins University (James Anthony, William Eaton, Philip Leaf), the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry Clinical Institute (Hans-Ulrich Wittchen), the Medical College of Virginia (Kenneth Kendler), the University of Miami (R. Jay Turner), the University of Michigan (Lloyd Johnston, Roderick Little), New York University (Patrick Shrout), the State University of New York at Stony Brook (Evelyn Bromet), and Washington University School of Medicine (Linda Cottler, Andrew Heath). A complete list of National Comorbidity Survey publications along with abstracts, study documentation, interview schedules, and the raw National Comorbidity Survey public use data files can be obtained directly from the National Comorbidity Survey home page on the World Wide Web (http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/).

|

|

Received Dec. 16, 1996; revision received June 9, 1997; accepted June 19, 1997. From the Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston; the Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York; and the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Address reprint requests to Dr. Kessler, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, 25 Shattuck St., Boston, MA 02115. Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-46376, MH-49098, and MH-52861; the National Institute on Drug Abuse (supplement to grant MH-46376); the W.T. Grant Foundation (grant 90135190) (Dr. Kessler); and Research Scientist Award MH-00507 (Dr. Kessler).

FIGURE 1. Kaplan-Meier Speed-of-Contact Curves of First Treatment Contacta for Major Depression/Dysthymia, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, Phobia, and Addictive Disorders for Subjects in the National Comorbidity Surveyb

aTreatment contact is defined as telling a physician (M.D., D.O., or student in training to become an M.D. or D.O.), mental health professional (psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker), or other professional (nurse, minister, priest, rabbi, or counselor) about the disorder. Speed of treatment contact is defined as the difference between retrospectively reported age at onset of the disorder and age at first treatment contact.

bAge at first treatment contact was assessed only once for major depression and dysthymia combined, so these two disorders are combined here. The same is true for simple phobia, social phobia, and agoraphobia (with or without panic), which are combined into one category, and for all addictive disorders (alcohol or drug abuse or dependence), which are combined into a separate category.

FIGURE 2. Kaplan-Meier Speed-of-Contact Curves of First Treatment Contacta for Phobiab in Subsamples Defined by Age at Onset of Phobia for Subjects in the National Comorbidity Survey

aTreatment contact is defined as telling a physician (M.D., D.O., or student in training to become an M.D. or D.O.), mental health professional (psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker), or other professional (nurse, minister, priest, rabbi, or counselor) about the disorder. Speed of treatment contact is defined as the difference between retrospectively reported age at onset of the disorder and age at first treatment contact.

bA ge at first treatment contact was assessed only once for simple phobia, social phobia, and ago raphobia (with or without panic), so these three disorders are combined into one category.

1. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:85–94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Wells KB, Manning W Jr, Benjamin B: A comparison of the effects of sociodemographic factors and health status on use of outpatient mental health services in HMO and fee-for-service plans. Med Care 1986; 24:949–960Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Katz SJ, Kessler RC, Frank RG, Leaf PJ, Lin E, Edlund MJ: The use of outpatient mental health services in the United States and Ontario: the impact of mental morbidity and perceived need for care. Am J Public Health 1997; 87:1136–1143Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Magruder KM, Norquist GS, Feil MB, Kopans B, Jacobs D: Who comes to a voluntary depression screening program? Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1615–1622Google Scholar

6. Regier DA, Hirschfeld RMA, Goodwin FK, Burke JD Jr, Lazar JB, Judd LL: The NIMH Depression Awareness, Recognition, and Treatment Program: structure, aims, and scientific basis. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:1351–1357Link, Google Scholar

7. Ustun TB, Sartorius N: Public health aspects of anxiety and depressive disorders. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1993; 8(suppl 1):15–20Google Scholar

8. Wells KB, Burnam MA, Camp P: Severity of depression in prepaid and fee-for-service general medical and mental health specialty practices. Med Care 1995; 33:350–364Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Dew MA, Dunn LO, Bromet E, Schulberg HC: Factors affecting help-seeking during depression in a community sample. J Affect Disord 1988; 14:223–234Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Olfson M, Pincus HA: Outpatient mental health care in nonhospital settings: distribution of patients across provider groups. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1353–1356Link, Google Scholar

11. Padgett DK, Patrick C, Burns BJ, Schlesinger HJ: Ethnicity and use of outpatient mental health services in a national insured population. Am J Public Health 1994; 84:222–226Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Temkin-Greener H, Clark KT: Ethnicity, gender, and utilization of mental health services in a Medicaid population. Soc Sci Med 1988; 26:989–996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Leaf PJ, Bruce ML, Tischler GL, Freeman DH Jr, Weissman MM, Myers JK: Factors affecting the utilization of specialty and general medical mental health services. Med Care 1988; 26:9–26Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Gallo JJ, Marino S, Ford D, Anthony JC: Filters on the pathway to mental health care, II: sociodemographic factors. Psychol Med 1995; 25:1149–1160Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Frank RG, McGuire TG: A review of studies of the impact of insurance on the demand and utilization of specialty mental health services. Health Serv Res 1986; 21:241–265Medline, Google Scholar

16. Keeler EB, Wells KB, Manning WG: The Demand for Episodes of Mental Health Services (R-3432-HHS.NIMH). Santa Monica, Calif, Rand Corp, 1986Google Scholar

17. Taube CA, Rupp A: The effect of Medicaid on access to ambulatory mental health care for the poor and near-poor under 65. Med Care 1986; 24:677–686Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Leaf PJ, Bruce ML, Tischler GL: The differential effect of attitudes on use of mental health services. Soc Psychiatry 1986; 21:187–192Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Wells KB, Golding JM, Hough RL, Burnam MA, Karno M: Factors affecting the probability of use of general and medical health and social/community services for Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites. Med Care 1988; 26:441–452Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Hu TW, Snowden LR, Jerrell JM, Nguyen TD: Ethnic populations in public mental health: services choice and level of use. Am J Public Health 1991; 81:1429–1434Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Phillips MA, Murrell SA: Impact of psychological and physical health, stressful events, and social support on subsequent mental health help seeking among older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994; 62:270–275Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Sherbourne CD: The role of social support and life stress events in use of mental health services. Soc Sci Med 1988; 27:1373–1377Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Goodman SH, Sewells DS, Jampol RC: On going to the counselor: contributions of life stress and social supports to the decision to seek psychological counseling. J Counseling Psychol 1984; 31:306–313Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Breakey WR, Kaminsky MJ: An assessment of Jarvis' law in an urban catchment area. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1982; 33:661–663Abstract, Google Scholar

25. Joseph AE, Boeckh JL: Locational variation in mental health care utilization dependent upon diagnosis: a Canadian example. Soc Sci Med 1981; 15:395–440Google Scholar

26. Loebel AD, Lieberman JA, Alvir JMJ, Mayerhoff DI, Geisler SH, Szymanski SR: Duration of psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1183–1188Link, Google Scholar

27. Johnstone EC, Crow TJ, Johnson AL, MacMillan JF: The Northwick Park study of first episodes of schizophrenia, I: presentation of the illness and problems relating to admission. Br J Psychiatry 1986; 148:115–120Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Lincoln CV, McGorry P: Who cares? pathways to psychiatric care for young people experiencing a first episode of psychosis. Psychiatr Serv 1995; 46:1166–1171Link, Google Scholar

29. Monroe SM, Simons AD, Thase ME: Onset of depression and time to treatment entry: roles of life stress. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991; 59:566–573Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Lish JD, Dime-Meenan S, Whybrow PC, Prince RA, Hirschfeld RMA: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association (DMDA) survey of bipolar members. J Affect Disord 1994; 31:281–294Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Lin KM, Inui TS, Kleinman AM, Womack WM: Sociocultural determinants of the help-seeking behavior of patients with mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis 1982; 170:78–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Kovacs M: Presentation and course of major depressive disorder during childhood and later years of the life span. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:705–715Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Giaconia RM, Renherz HZ, Silverman AB, Pakiz B, Frost AK, Cohen EL: Ages of onset of psychiatric disorders in a community population of older adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:706–717Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Hoehn-Saric RE, Hazlett RL, McLeod DR: Generalized anxiety disorder with early and late onset of anxiety symptoms. Compr Psychiatry 1993; 34:291–298Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Kessler RC: Sex differences in the use of health services, in Illness Behavior: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Edited by McHugh S. New York, Plenum, 1986, pp 135–148Google Scholar

36. Kessler RC, Little RJA, Groves RM: Advances in strategies for minimizing and adjusting for survey nonresponse. Epidemiol Rev 1995; 17:192–204Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. World Health Organization: Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 1.0. Geneva, WHO, 1990Google Scholar

38. Wittchen H-U: Reliability and validity studies of the WHO-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res 1994; 28:57–84Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Wittchen H-U, Kessler RC, Zhao S, Abelson J: Reliability and clinical validity of UM-CIDI DSM-III-R generalized anxiety disorder. J Psychiatr Res 1995; 29:95–110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz MS: The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:979–986Link, Google Scholar

41. Wittchen H-U, Zhao S, Abelson JM, Abelson JL, Kessler RC: Reliability and procedural validity of UM-CIDI DSM-III-R phobic disorders. Psychol Med 1996; 25:1169–1177Crossref, Google Scholar

42. Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC: The lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:313–321Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Kaplan EL, Meier P: Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Statistical Assoc 1958; 53:281–284Crossref, Google Scholar

44. Efron B: Logistic regression, survival analysis, and the Kaplan-Meier curve. J Am Statistical Assoc 1988; 83:415–425Crossref, Google Scholar

45. Kish L, Frankel MR: Inference from complex samples (with discussion). J Royal Statistical Assoc Series B 1974; 36:1–37Google Scholar

46. SAS Introductory Guide, release 6.03. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1988Google Scholar

47. Dulcan MK, Costello EJ, Costello AJ, Edelbrock C, Brent D, Janiszewski S: The pediatrician as gatekeeper to mental health care for children: do parents' concerns open the gate? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1990; 29:453–458Google Scholar

48. Costello EJ, Janiszewski S: Who gets treated? factors associated with referral in children with psychiatric disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1990; 81:523–529Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Bhugra D: Attitudes towards mental illness: a review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989; 80:1–12Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Ridgely MS, Goldman HH: Mental health insurance, in Handbook on Mental Health Policy in the United States. Edited by Rochefort DA. Westport, Conn, Greenwood Press, 1989, pp 341–361Google Scholar

51. Rogler LH, Cortes DE: Help-seeking pathways: a unifying concept in mental health care. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:554–561Link, Google Scholar

52. McElroy SL, Keck PE, Friedman LM: Minimizing and managing antidepressant side effects. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:49–55Medline, Google Scholar

53. Jefferson JW: Social phobia: a pharmacologic treatment overview. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56(suppl 5):18–24Google Scholar

54. Leonard BE: New approaches to the treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 4):26–33Google Scholar

55. Zarate R, Agras WS: Psychosocial treatment of phobia and panic disorders. Psychiatry 1994; 57:133–141Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Katerndahl DA, Realini JP: Where do panic attack sufferers seek care? J Fam Pract 1995; 40:237–243Google Scholar

57. Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin E: Panic disorder: relationship to high medical utilization. Am J Med 1992; 92(suppl 1A):7S–11SGoogle Scholar