Relationship Between Duration of Untreated Psychosis and Outcome in First-Episode Schizophrenia: A Critical Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The duration of untreated psychosis may influence response to treatment, reflecting a potentially malleable progressive pathological process. The authors reviewed the literature on the association of duration of untreated psychosis with symptom severity at first treatment contact and with treatment outcomes and conducted a meta-analysis examining these relationships. METHOD: English-language articles on duration of untreated psychosis published in peer-reviewed journals through July 2004 were reviewed. Studies that quantitatively assessed the duration of untreated psychosis; identified study subjects who met the criteria for nonaffective psychotic disorders at or close to first treatment; employed cross-sectional analyses of duration of untreated psychosis and of baseline symptoms, neurocognition, brain morphology, or functional measures or prospectively analyzed symptom change, response, or relapse; assessed psychopathology with clinician-rated instruments; and reported subjects’ diagnoses (a total of 43 publications from 28 sites) were included in the meta-analysis. RESULTS: Shorter duration of untreated psychosis was associated with greater response to antipsychotic treatment, as measured by severity of global psychopathology, positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and functional outcomes. At the time of treatment initiation, duration of initially untreated psychosis was associated with the severity of negative symptoms but not with the severity of positive symptoms, general psychopathology, or neurocognitive function. CONCLUSIONS: Duration of untreated psychosis may be a potentially modifiable prognostic factor. Understanding the mechanism by which duration of untreated psychosis influences prognosis may lead to better understanding of the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and to improved treatment strategies.

Schizophrenia is a chronic, disabling disorder for most affected individuals. Although vulnerability to schizophrenia is likely to be related to genetic and environmental factors that influence early brain development, the disorder is only minimally expressed until adolescence or young adulthood. Despite historical pessimism about prognosis, more recent studies suggest that early intervention can improve outcome (1). These findings have stimulated great interest and enthusiasm for the idea that intervention at or even prior to the onset of the first episode might improve response to antipsychotic treatment and long-term outcome. Numerous “early psychosis” or “prodromal” clinics have been developed to facilitate early interventions (2–5). Efforts at early identification and treatment are based in part on the assumption that through an as-yet unknown process, illness duration causally influences treatment responsivity and outcome (6).

Understanding the causes and consequences of untreated psychosis is important for at least two reasons. First, the duration of psychosis before initiation of treatment is a potentially modifiable prognostic factor, and understanding its relation to outcome could lead to improved therapeutic strategies and public health initiatives. Second, a relationship of duration of untreated psychosis to outcome may indicate a neurodegenerative process and so have important implications for understanding the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Alternatively, the length of initially untreated psychosis may be related to the severity of illness and thus may be a marker rather than a determinant of outcome (7).

Given the growing interest and debate in this area, a meta-analysis and review of the evidence bearing on the issue of illness duration and prognosis are relevant. We used meta-analytic techniques to evaluate the association of duration of untreated psychosis with symptom severity and function at first treatment contact and in response to antipsychotic treatment. We present the results of the meta-analysis and review the relationship of duration of untreated psychosis to relapse risk, neurocognitive function, and brain morphology. The methodological limitations of current research on duration of untreated psychosis are discussed, and strategies for further research are suggested.

Method

An electronic MEDLINE search strategy was used to identify relevant English-language studies published through July 2004. The following key words were used in the search: (“duration of untreated psychosis” OR “DUP” OR “outcome” OR “recovery”) AND (“psychosis” OR “schizophrenia” OR “schizoaffective disorder” OR “schizophreniform disorder”) AND (“first episode” OR “first admission”). This search yielded 497 references. The titles and abstracts of these references were searched to eliminate obviously irrelevant studies, yielding 125 publications for detailed review. The reference sections of these 125 publications also were reviewed, and three other potentially relevant publications were identified.

Studies were included if the following criteria were met: 1) the study quantitatively assessed the duration of initially untreated psychosis; 2) most study subjects were identified at or close to first treatment; 3) the study used cross-sectional analyses of the duration of untreated psychosis and baseline symptom, brain morphology, neurocognition, or functional measures or prospectively analyzed symptom change or the proportion of subjects who met the study definition of “treatment response” or “relapse”; 4) psychopathology was assessed by using clinician-rated instruments and the summary statistics were reported; and 5) the study reported subjects’ diagnoses and most of the subjects met the standard diagnostic system criteria for a nonaffective psychotic disorder. In addition, the following rules were applied: 1) if a study included subjects with affective psychotic disorders but reported results separately for the nonaffective psychotic disorder subgroup, then the subgroup results were used; 2) when more than one study from the same research group reported results on overlapping subject groups, the study with the largest number of subjects for the particular outcome was included; and 3) when study results were reported for multiple follow-up periods, the longest follow-up period was used, with one exception—a study with both short-term and long-term follow-up in which the results for the long-term follow-up were reported for a relatively small subgroup of subjects (8, 9). A total of 43 publications from 28 sites met the inclusion criteria (2, 8–49). Because the literature was sparse, we included one additional study (50) in the review of the relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and relapse. That study used chart review to determine relapse and self-report and parental report to determine duration of untreated psychosis and symptom severity. Table 1 summarizes key features of these studies.

Statistical Methods

The statistical meta-analyses was based on studies that included quantitative assessment of function with the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale or the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (53) and quantitative assessment of psychopathology with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (54), the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, the Association for Methodology and Documentation in Psychiatry system (55), the Present State Examination (56), the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (57), or the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (58), as specified in Table 1. Separate measures for effect sizes in Hedges’s gu and correlation coefficients were calculated for studies analyzing duration of untreated psychosis as a categorical variable (long versus short duration) and for the studies analyzing duration of untreated psychosis as a continuous variable, respectively. All analyses were performed using SAS version 8.0 software (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). Fixed-effects models were used after checking the homogeneity among studies. Fixed-effects estimations for effect sizes were withheld if the homogeneity assumption was violated, but a random-effects model was not fitted because of the small number of studies available in this analysis. We checked for publication bias by means of Begg’s funnel plot.

The variety of distinctive clinical definitions and statistical approaches used to evaluate “treatment response” limits the effective sample size required by the analytical meta-analysis approach. We instead categorized the studies according to their statistical approaches and tabulated their findings accordingly.

Results

Duration of Untreated Psychosis and First-Episode Treatment Outcome

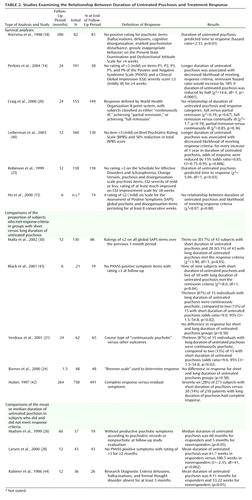

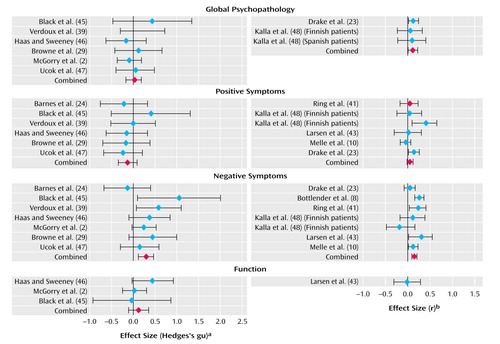

Figure 1 illustrates the individual study results and combined study summary statistics examining the relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and symptom response in patients with first-episode psychosis. The results of studies that used comparisons of means are summarized on the left side of Figure 1, and the results of studies that used correlational methods are summarized on the right side of Figure 1.

The duration of treatment varied considerably in these studies, ranging from the end of the first hospitalization to 15 years. Shorter duration of untreated psychosis was associated with greater response to antipsychotic treatment, as measured by improvement or endpoint severity of global psychopathology (five studies), positive symptom severity (13 studies), and negative symptom severity (14 studies). The effect size for duration of untreated psychosis and symptomatic response for the combined (all studies) statistic was consistently significant and of small to moderate magnitude (global psychopathology: combined Hedges’s gu=0.51 [95% confidence interval (CI)=0.33–0.69]; positive symptom severity: combined Hedges’s gu=0.41 [95% CI=0.22–0.59]; negative symptom severity: combined Hedges’s gu=0.3 [95% CI=0.14–0.46]; global psychopathology: combined r=0.29 [95% CI=0.2–0.36]; positive symptom severity: combined r=0.27 [95% CI=0.21–0.31]; negative symptom severity: combined r=0.23 [95% CI=0.17–0.27]). Similarly, the effect size examining the relationship of duration of untreated psychosis and global functional outcome (measured with the GAF or GAS) (seven studies), which takes into account symptom severity and social and vocational function, was also consistently statistically significant and of small to moderate magnitude (combined Hedges’s gu=0.6 [95% CI=0.4–0.8]; combined r=0.21 [95% CI=0.13–0.28]).

Duration of Untreated Psychosis and “Response”

Fourteen studies examined the relationship of duration of untreated psychosis and likelihood of meeting response criteria for the initial treatment of a first psychotic episode. The data analytic strategies used in these studies varied and included 1) survival analysis (six studies), 2) comparison of the proportion of subjects who met response criteria in groups with short versus long duration of untreated psychosis (five studies), and 3) comparison of the mean duration of untreated psychosis in subjects who did and did not meet study response criteria (three studies). Because of differences in the methods of analysis used in these studies, meta-analytic techniques were not used to combine the results. The results of these studies are summarized in Table 2.

Statistical comparisons using survival analysis are the most appropriate for these purposes, because this technique adjusts for different lengths of follow-up and for the fact that a subject may not have met the response criteria before discontinuing from the study. Unlike the other analytic strategies, survival analysis accounts for time in study and so is less likely to produce biased results if the likelihood of dropout is influenced by treatment response. Four of the six studies using survival analysis found a significant relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and treatment response. Possible reasons for the differences in the study results include variation in the definitions of treatment response and in the lengths of the follow-up period.

Duration of Untreated Psychosis and Other Functional Outcome Measures

The results of studies evaluating the association between duration of untreated psychosis and a variety of other functional outcome measures are mixed. One study using a modified GAF in which symptoms and function were rated separately found duration of untreated psychosis to be significantly associated with 3-month global symptom severity and global function outcomes (r2=–0.41 and r2=–0.30, respectively, p<0.01) (10). In another study that used a modified version of the GAS and logistic regression modeling, duration of untreated psychosis was significantly related to function at 5-, 10-, 15-, and 20-year follow-ups (odds ratio=1.84–4.91, p<0.05) (49). Duration of untreated psychosis was related to overall function as measured by the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule at 2- and 15-year follow-up (11), to Heinrich-Carpenter Quality of Life at 1-year follow-up (Pearson’s r=–0.29, p=0.001) (12), and to 2-year follow-up (Pearson’s r=–0.20, p<0.05) (13). In contrast, another study did not find a relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and social or vocational function at 2-year follow-up as measured by the Heinrich-Carpenter Quality of Life (14). In a study that included the “Psychiatric Status You Currently Have” interview, no relationship was found between duration of untreated psychosis and 6-month social and vocational outcomes (15). In a study in which the Wisconsin Quality of Life Index was administered at 1-year follow-up, a significant relationship was found between duration of untreated psychosis and social function (r=–0.23, p<0.05), but this relationship did not remain significant in a regression model that included the variables of premorbid adjustment, residual symptom severity, and adherence to medication (16).

Duration of Untreated Psychosis and Relapse Risk

Even with complete recovery from a first psychotic episode, relapse risk remains very high. More than 90% of patients experience a relapse within 5 years of initial treatment response (17, 18, 59), and maintenance antipsychotic treatment is a strong predictor of relapse risk in most (17, 19, 60, 61) but not all (12, 20) studies. Studies that examined the association between duration of untreated psychosis and relapse risk showed mixed results. One study that used parent and self-report ratings to evaluate psychopathology and duration of untreated psychosis found a significant relationship between longer duration of untreated psychosis and relapse risk (assessed by chart review) at 6-year follow-up (50). In a second study this relationship approached significance (p=0.08) at 2-year follow-up (21). In a prospective 2-year study comparing maintenance antipsychotic medication to placebo, the relapse rate was high in both the antipsychotic-treated group (45%) and the placebo (62%) group, and duration of untreated psychosis before initiation of antipsychotic treatment predicted relapse in both groups (22). Two other studies, however, found no relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and risk of relapse after recovery from a first episode of psychosis (17, 18).

Potential Confounding Factors

The interpretation of the consistent findings that duration of untreated psychosis is associated with the level of recovery from a first psychotic episode depends on whether the relationship is confounded through an association with vulnerability factors for a poor prognostic subtype of schizophrenia, social factors not directly related to the schizophrenia pathophysiology, or both. A variety of potentially confounding factors have been considered, including chronological age (8, 9, 13, 20, 23), age at illness onset (12, 15, 19, 24), age at first hospitalization (9, 62), sex (8, 9, 12, 23, 25–27, 63–66), premorbid functioning (9, 12–15, 21, 28, 29, 63, 64), mode of onset (67, 68), diagnosis (59, 69), education (12, 23, 62), marital and socioeconomic status (9, 64), family history of psychiatric illness (12, 26), ethnicity (23), and duration or continuity of antipsychotic treatment (12, 13, 16, 19). Duration of untreated psychosis has been shown to be longer for subjects with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, compared to mood disorders with psychotic features (2, 20). Given that psychotic affective disorders may have both a better prognosis and a shorter duration of untreated psychosis than nonaffective psychosis, most research groups either exclude individuals with affective psychosis or report data separately for subjects with schizophrenia spectrum psychotic disorders (Table 1).

Most studies find that the relationship of duration of untreated psychosis and outcome persists after adjustment for potential confounders. In particular, poor premorbid function and mode of onset are theoretically important variables that could confound the relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome, because both could lead to delays in recognizing illness, and both are associated with poor prognosis (7). Studies that modeled the relationship of duration of untreated psychosis to treatment response and included adjustment for premorbid function (9, 10, 12–14, 18, 21, 28, 30, 63) or mode of onset (9) consistently found that duration of untreated psychosis is an independent predictor, although the strength of the relationship varied.

Duration of Untreated Psychosis and Symptom Severity at First Treatment Contact

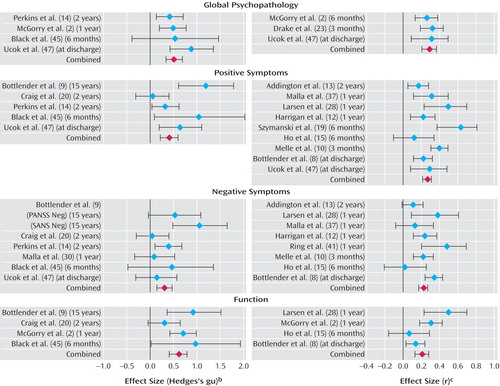

Figure 2 summarizes the results of studies that analyzed the relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and symptom severity at first treatment contact. The results of studies that used comparisons of means are summarized on the left side of Figure 2, and the results of studies that used correlational methods are summarized on the right side of Figure 2.

Greater severity of negative symptoms at first treatment contact was significantly associated with longer duration of untreated psychosis (combined Hedges’s gu=0.28, 95% CI=0.1–0.45; combined correlation: r=0.15, 95% CI=0.9–0.21). Duration of untreated psychosis was not related to severity of global psychopathology or positive symptoms or to global assessments of function (assessed with the GAF or GAS) at first treatment contact.

Duration of Untreated Psychosis and Neurocognition

Eight studies reported in nine publications examined the relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and baseline neurocognitive function (13, 24, 27, 31–33) or neurocognitive function after a period of antipsychotic treatment (13, 34–36). Table 1 summarizes the neurocognitive test batteries used in each of these studies. These studies generally found no relationship, except as noted here. One study of 42 first-episode subjects found longer duration of untreated psychosis associated with worse performance on WAIS digit symbol and comprehension subtests (35). In this study, longer duration of untreated psychosis was also associated with estimated cognitive decline before treatment (assessed as the ratio of the WAIS information and vocabulary subtest scores, which are relatively intact in schizophrenia, to the WAIS digit symbol subtest score, which is believed to decline in schizophrenia). In a second study of 136 subjects that measured neurocognitive function with the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery, there was a significant relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and performance on an attentional set-shifting task that measured aspects of executive function (31). An earlier analysis of a subsample from this same study (the West London First Episode Study) found no associations between duration of untreated psychosis and IQ or intellectual decline from the premorbid level, oculomotor functioning, memory, attention, and executive function (24).

Duration of Untreated Psychosis and Brain Morphology

The five studies that examined the neuromorphological correlates of initially untreated psychosis generally found no relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and brain morphology. Four of these studies (27, 33, 37, 38) found no significant correlation between duration of untreated psychosis and several magnetic resonance imaging volumetric measures of brain structures, although the fifth study (26) found that longer duration of untreated psychosis was significantly correlated with cortical (mainly frontal) volume reduction and sulcal enlargement at baseline as measured by computed tomography. Although the evidence suggests that there is no relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and brain morphology, definitive conclusions cannot be drawn because of the methodological limitations of existing studies.

Discussion

The major results of this meta-analysis and review are as follows: 1) A prolonged period of psychosis experienced before the initiation of antipsychotic treatment is associated with lower levels of symptomatic and functional recovery from the first psychotic episode. This association appears to be independent of the effect of other variables also associated with prognosis and to persist into the chronic stage of illness. 2) The duration of initially untreated psychosis does not appear to be associated with neurocognitive function at first treatment contact. 3) The duration of initially untreated psychosis is associated with severity of negative symptoms but not with severity of positive symptoms or general psychopathology at the time of initial clinical evaluation. Most studies identified subjects at first hospitalization. Because a threshold severity of positive symptoms and functional impairment is usually required for hospitalization, symptom severity at the time of hospitalization may be strongly related to this threshold, which would obscure any relationship with duration of untreated psychosis. Studies with epidemiological samples are needed to address this issue. 4) Existing studies do not find a relationship between duration of initially untreated psychosis and abnormalities in brain morphology, although further study is needed. 5) The literature on the association between duration of untreated psychosis and risk of subsequent psychotic episodes is not of sufficient strength to draw conclusions. Further study is needed to determine whether duration of untreated psychosis influences relapse risk in patients, and such studies should consider continuity of maintenance treatment.

Implications for Understanding the Neurobiological Aspects of Schizophrenia

The findings that duration of untreated psychosis is associated with the level of symptomatic improvement and the likelihood of remission of a first psychotic episode are consistent with the theory that psychosis is a clinical manifestation of a progressive pathological process against which antipsychotic medications may be protective. In particular, it is important to note that longer duration of untreated psychosis is associated with both severity of negative symptoms at first treatment contact and also with the response of negative symptoms to treatment. Given that negative symptoms may be less responsive to antipsychotic treatment than positive symptoms, it is interesting to note that individuals with shorter duration of untreated psychosis experienced greater negative symptom reduction in the studies we reviewed. Long duration of untreated psychosis may limit the potential responsiveness of negative symptoms to treatment.

An alternative interpretation is that duration of untreated psychosis is directly influenced and thus confounded by an as yet unidentified neurodevelopmental or genetically based factor related to treatment responsiveness (70). It is noteworthy that the relationship of duration of untreated psychosis to outcome was consistent across follow-up periods that ranged from a few weeks to as long as 15 years, suggesting that earlier intervention may impact long-term illness course.

Studies are thus needed to assess directly the long-term prognostic effect of maintenance antipsychotic treatment on outcome. The variable results for association of duration of untreated psychosis with relapse risk suggests either that early intervention may not (or only minimally) affect risk of subsequent episodes or that any neuroprotection afforded by antipsychotics may be attenuated after medication is discontinued. A few studies considered whether antipsychotic medication was prescribed or taken during the follow-up period (15, 16, 19, 20, 39). Data from studies of first-episode patients showed that over a 6-month period between 33% and 44% of patients are inadequately adherent (60, 71), and by 1 year as many as 59% may be either inadequately adherent or completely nonadherent (61). Other studies suggested that psychotic symptoms subsequently reemerge in almost all of these patients (25, 59).

With recurrent episodes patients may be at risk for the development of residual symptoms that only partially respond to available treatments (6, 72). Recent data from longitudinal neuroimaging studies find ventricular enlargement and decrease in gray and white matter volumes in first-episode patients with evidence of progressive changes over time (73–75). It is not known whether early intervention and long-term maintenance treatment may prevent the progressive loss of gray matter. One implication of these findings is that the effect of active psychosis on outcome in schizophrenia could be demonstrated more conclusively if the total duration of active psychosis is considered (32).

Implications for Reduction of Duration of Untreated Psychosis Through Early Intervention

An association between duration of untreated psychosis and clinical outcome offers hope that early intervention programs that are effective in reducing the length of the initial psychotic episode may enhance the likelihood of recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia and perhaps reduce cumulative morbidity. Ameliorating the symptoms of initial psychosis may not only lessen the immediate suffering and burden of disease experienced by patients and their families, but it may also improve long-term prognosis by limiting progression of the illness and preserving a person’s ability to respond to antipsychotic medication. In future studies it will be particularly important to evaluate the effect of reduction of the duration of untreated psychosis on initial negative symptom severity and negative symptom response to treatment.

The duration of untreated psychosis may be influenced by factors closely related to the underlying pathology of the disease, including poor premorbid function and insidious onset. At the same time, factors unrelated to disease pathology, such as socioeconomic status, access to and availability of care, recognition of illness, and stigma, also may contribute to duration of untreated psychosis (62, 76–79). From a public health perspective, the development of strategies to recognize and intervene soon after the onset of psychosis is an important task.

As appears to be true for Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease (80), schizophrenia may involve a progressive pathological process that is well developed by the time the frank psychopathology of schizophrenia emerges. Because prodromal signs and symptoms are phenomenologically continuous with the symptoms of psychosis, it is possible that any neuroprogressive process that underlies psychosis may be under way long before the cumulative threshold of florid psychosis is reached (81). It is interesting to note that a recent study reported that temporal lobe gray matter volume reductions were present and progressed in prodromal patients who subsequently developed psychosis (82). Further research is needed to determine if initiation of treatment before the formal onset of psychosis, during the prodrome, will improve symptomatic and functional outcome.

Methodological Considerations

An inherent difficulty in assessing the length of untreated psychosis is the fact that the assessments are almost always retrospective. In addition to this practical difficulty, no specific marker of emergent psychosis has been identified, and the beginning point of untreated psychosis, as identified by clinical definitions, remains elusive. In the early stages of illness, psychosis may briefly develop and spontaneously subside, only to recur many months later. Until a consensus definition emerges, research definitions should specify the severity and frequency criteria for psychosis onset. The definition of onset of treatment is elusive because the initial course of antipsychotic treatment may be variable in length and it is not known if a critical duration of treatment is needed to affect prognosis. Given these uncertainties, it may be prudent to specify the treatment duration required in the definition of treatment onset.

Some studies of first-episode patients have stipulated a maximum duration of untreated psychosis as an inclusion criteria (14, 40, 41, 83). If the magnitude of the effect of duration of untreated psychosis on outcome continues to grow past the limits imposed by these study inclusion criteria, then these studies will underestimate the effect of duration of untreated psychosis on outcome. In addition, most studies identify subjects at first hospitalization and thus do not include individuals with milder symptoms who do not require inpatient treatment. Epidemiological cohorts that include the full spectrum of illness severity and of duration of untreated psychosis are needed to understand fully the relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome.

As with all variables in statistical analyses, the underlying structure and distribution of duration of untreated psychosis warrant careful consideration. The distribution is typically highly skewed. The few outliers with extremely long duration of untreated psychosis may serve as leverage points and exert undue influence on the study conclusions. Analyses that use duration of untreated psychosis in its original scale (e.g., weeks, months) have various statistical difficulties and may even lead to erroneous findings. This approach was taken by some of the studies reviewed here (Table 1).

To avoid these problems, the most conservative approach is to dichotomize duration of untreated psychosis into long and short duration on the basis of either a median split or prespecified time points. Although dichotomization addresses the problem of skewness in duration of untreated psychosis, a great deal of information is lost. In addition, study-specific and often arbitrary cutoff time points interfere with generalization. Finally, no good theoretical rationale for defining “short” and “long” duration of untreated psychosis is available, because it is unknown if there is a critical time point for intervention, beyond which further delays in treatment will not affect prognosis (84). An alternative approach is to use an ordinal scale for duration of untreated psychosis and to use nonparametric statistical procedures for analysis. Compared to categorization, this approach preserves more information, but it is limited in its capacity for modeling, especially when complex covariate structures are involved. A preferable procedure may be to perform a data transformation, such as logarithmic transformations. Such data transformation procedures would appropriately manage skewness, moderate leverage data points, maximize statistical power, and minimize the risk of truncating the variable at a point in time that is not clinically meaningful.

Future Study

Studies that advance our understanding of the mechanism responsible for the relationship of duration of psychosis and outcome will most likely provide critical information about the neuropathology of schizophrenia. The evidence for clinical deterioration after a prolonged period of initially untreated psychosis, manifested through the development of secondary resistance to antipsychotic treatment and progressive functional impairments, suggests that at least part of the clinical deterioration characteristic of schizophrenia is mediated by a progressive pathophysiological process. Evolving theoretical models that attempt to explain neuroprogression include dysregulation of neural networks that involve potentially neurotoxic neurotransmitters (85) and an acceleration of normal synaptic pruning or apoptotic processes during adolescence (86). Longitudinal studies, especially those that attempt to look at change in brain structure and function beginning at the premorbid or prodromal stages of the illness and extending through the first episode, are likely to increase our understanding of the nature and timing of the neurochemical, neuroanatomical, and clinical pathways that underlie clinical deterioration in schizophrenia.

A putative neuroprogressive component to schizophrenia may not be expressed symptomatically in all psychopathological domains, and our understanding of what mediates the effect of duration of untreated psychosis on initial treatment responsiveness will be guided by determining which aspects of schizophrenic illness are stable neurodevelopmental manifestations and which aspects emerge and progress over time. For example, previous studies suggested that progressive decline of neurocognitive function occurs before the onset of any other clinical manifestation of illness (87, 88). Cognitive decline may precede the development of other clinical symptoms, which would explain why we did not find a relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and neurocognitive function in the studies included in this review.

Another important issue relates to the observation of treatment resistance in individuals with a duration of untreated psychosis as short as 4 weeks (15, 20), as well as preserved responsiveness to antipsychotic treatment in individuals with duration of untreated psychosis longer than 5 years (15, 20, 89). Variability in treatment responsiveness may reflect fundamentally different neurobiological processes involved in the development and progression of symptoms. Given the implications for prevention and for understanding the sequence of pathophysiological events underlying treatment response, strategies for distinguishing primary and secondary treatment resistance are crucial. Also, potential protective factors that may contribute to the preservation of treatment responsiveness and to improved clinical outcome in patients with a long duration of untreated psychosis merit further attention, as they may lead to discovery of new therapeutic dimensions.

Conclusions

Although further study is needed, duration of untreated psychosis has emerged as an independent predictor of the likelihood and extent of recovery from an initial episode of schizophrenia, albeit with small to moderate effect, and so is a potentially modifiable prognostic factor. Understanding the mechanisms by which duration of untreated psychosis influences prognosis may lead to better understanding of the schizophrenia disease process.

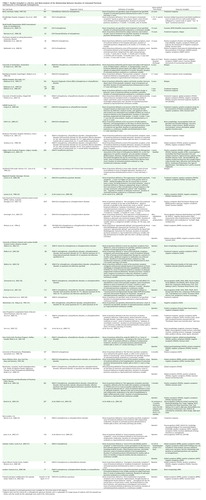

|

|

Received March 10, 2003; revisions received May 21 and Sept. 28, 2004; accepted Oct. 1, 2004. From the Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina School of Medicine. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Perkins, Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, CB 7160, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; diana_[email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants K23-MH-01905, U01-MH-066069, and P50-MH-064065 (Dr. Perkins); T32-MH-019111 (Dr. Boteva); and P50-MH-064065 and MH-33127 to the University of North Carolina Mental Health Neuroscience Clinical Research Center (Dr. Lieberman); and by the Foundation of Hope of Raleigh, North Carolina.

Figure 1. Effect Size Estimates for the Relationship Between Duration of Untreated Psychosis and Treatment Responsea

aStudies are listed with the duration of follow-up indicated in parentheses.

bHedges’s gu was used for analysis of results from studies in which duration of untreated psychosis was defined as a categorical variable (e.g., long versus short).

cThe correlation coefficient (r) was used for analysis of result from studies in which duration of untreated psychosis was defined as a continuous variable.

Figure 2. Effect Size Estimates for the Relationship Between Duration of Untreated Psychosis and Symptom Severity at First Treatment Contact

aHedges’s gu was used for analysis of results from studies in which duration of untreated psychosis was defined as a categorical variable (e.g., long versus short).

bThe correlation coefficient (r) was used for analysis of result from studies in which duration of untreated psychosis was defined as a continuous variable.

1. Lieberman JA, Perkins D, Belger A, Chakos M, Jarskog F, Boteva K, Gilmore J: The early stages of schizophrenia: speculations on pathogenesis, pathophysiology, and therapeutic approaches. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 50:884–897Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. McGorry PD, Edwards J, Mihalopoulos C, Harrigan SM, Jackson HJ: EPPIC: an evolving system of early detection and optimal management. Schizophr Bull 1996; 22:305–326Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Linszen D, Lenior M, de Haan L, Dingemans P, Gersons B: Early intervention, untreated psychosis and the course of early schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998; 172:84–89Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Malla AK, Norman RM, Manchanda R, McLean TS, Harricharan R, Cortese L, Townsend LA, Scholten DJ: Status of patients with first-episode psychosis after one year of phase-specific community-oriented treatment. Psychiatr Serv 2002; 53:458–463Link, Google Scholar

5. Johannessen JO, McGlashan TH, Larsen TK, Horneland M, Joa I, Mardal S, Kvebaek R, Friis S, Melle I, Opjordsmoen S, Simonsen E, Ulrik H, Vaglum P: Early detection strategies for untreated first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 2001; 51:39–46Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lieberman JA, Sheitman B, Chakos M, Robinson D, Schooler N, Keith S: The development of treatment resistance in patients with schizophrenia: a clinical and pathophysiologic perspective. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1998; 18:20S-24SCrossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. McGlashan TH: Duration of untreated psychosis in first-episode schizophrenia: marker or determinant of course? Biol Psychiatry 1999; 46:899–907Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bottlender R, Strauss A, Moller HJ: Impact of duration of symptoms prior to first hospitalization on acute outcome in 998 schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Res 2000; 44:145–150Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Bottlender R, Sato T, Jager M, Wegener U, Wittmann J, Strauss A, Moller HJ: The impact of the duration of untreated psychosis prior to first psychiatric admission on the 15-year outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2003; 62:37–44Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Melle I, Larsen TK, Haahr U, Friis S, Johannessen JO, Opjordsmoen S, Simonsen E, Rund BR, Vaglum P, McGlashan T: Reducing the duration of untreated first-episode psychosis: effects on clinical presentation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61:143–150Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Wiersma D, Wanderling J, Dragomirecka E, Ganev K, Harrison G, an der Heiden W, Nienhuis FJ, Walsh D: Social disability in schizophrenia: its development and prediction over 15 years in incidence cohorts in six European centres. Psychol Med 2000; 30:1155–1167Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Harrigan SM, McGorry PD, Krstev H: Does treatment delay in first-episode psychosis really matter? Psychol Med 2003; 33:97–110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Addington J, van Mastrigt S, Addington D: Duration of untreated psychosis: impact on 2-year outcome. Psychol Med 2004; 34:277–284Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Perkins D, Lieberman J, Gu H, Tohen M, McEvoy J, Green A, Zipursky R, Strakowski S, Sharma T, Kahn R, Gur R, Tollefson G: Predictors of antipsychotic treatment response in patients with first-episode schizophrenia, schizoaffective and schizophreniform disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 185:18–24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Ho B-C, Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Nopoulos P, Miller D: Untreated initial psychosis: its relation to quality of life and symptom remission in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:808–815; correction, 2001; 158:986Google Scholar

16. Malla AK, Norman RM, Manchanda R, Townsend L: Symptoms, cognition, treatment adherence and functional outcome in first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med 2002; 32:1109–1119Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, Bilder R, Goldman R, Geisler S, Koreen A, Sheitman B, Chakos M, Mayerhoff D, Lieberman JA: Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:241–247Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Wiersma D, Nienhuis FJ, Slooff CJ, Giel R: Natural course of schizophrenic disorders: a 15-year followup of a Dutch incidence cohort. Schizophr Bull 1998; 24:75–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Szymanski SR, Cannon TD, Gallacher F, Erwin RJ, Gur RE: Course of treatment response in first-episode and chronic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:519–525Link, Google Scholar

20. Craig TJ, Bromet EJ, Fennig S, Tanenberg-Karant M, Lavelle J, Galambos N: Is there an association between duration of untreated psychosis and 24-month clinical outcome in a first-admission series? Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:60–66Link, Google Scholar

21. Verdoux H, Liraud F, Bergey C, Assens F, Abalan F, van Os J: Is the association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome confounded? a two year follow-up study of first-admitted patients. Schizophr Res 2001; 49:231–241Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Crow TJ, MacMillan JF, Johnson AL, Johnstone EC: A randomised controlled trial of prophylactic neuroleptic treatment. Br J Psychiatry 1986; 148:120–127Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Drake RJ, Haley CJ, Akhtar S, Lewis SW: Causes and consequences of duration of untreated psychosis in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 177:511–515Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Barnes TR, Hutton SB, Chapman MJ, Mutsatsa S, Puri BK, Joyce EM: West London first-episode study of schizophrenia: clinical correlates of duration of untreated psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 177:207–211Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Alvir JMJ, Geisler S, Koreen A, Sheitman B, Chakos M, Mayerhoff D, Bilder R, Goldman R, Lieberman JA: Predictors of treatment response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:544–549Link, Google Scholar

26. Madsen AL, Karle A, Rubin P, Cortsen M, Andersen HS, Hemmingsen R: Progressive atrophy of the frontal lobes in first-episode schizophrenia: interaction with clinical course and neuroleptic treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999; 100:367–374Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Hoff AL, Sakuma M, Razi K, Heydebrand G, Csernansky JG, DeLisi LE: Lack of association between duration of untreated illness and severity of cognitive and structural brain deficits at the first episode of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1824–1828Link, Google Scholar

28. Larsen TK, Moe LC, Vibe-Hansen L, Johannessen JO: Premorbid functioning versus duration of untreated psychosis in 1 year outcome in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 2000; 45:1–9Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Browne S, Clarke M, Gervin M, Waddington JL, Larkin C, O’Callaghan E: Determinants of quality of life at first presentation with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176:173–176Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Malla AK, Norman RMG, Manchanda R, Ahmed MR, Scholten D, Harricharan R, Cortese L, Takhar J: One year outcome in first episode psychosis: influence of DUP and other predictors. Schizophr Res 2002; 54:231–242Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Joyce E, Hutton S, Mutsatsa S, Gibbins H, Webb E, Paul S, Robbins T, Barnes T: Executive dysfunction in first-episode schizophrenia and relationship to duration of untreated psychosis: the West London Study. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2002; 43:S38-S44Google Scholar

32. Norman RM, Townsend L, Malla AK: Duration of untreated psychosis and cognitive functioning in first-episode patients. Br J Psychiatry 2001; 179:340–345Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Ho B-C, Alicata D, Ward J, Moser DJ, O’Leary DS, Arndt S, Andreasen NC: Untreated initial psychosis: relation to cognitive deficits and brain morphology in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:142–148Link, Google Scholar

34. Rund BR, Melle I, Friis S, Larsen TK, Midbøe LJ, Opjordsmoen S, Simonsen E, Vaglum P, McGlashan T: Neurocognitive dysfunction in first-episode psychosis: correlates with symptoms, premorbid adjustment, and duration of untreated psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:466–472Link, Google Scholar

35. Amminger GP, Edwards J, Brewer WJ, Harrigan S, McGorry PD: Duration of untreated psychosis and cognitive deterioration in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2002; 54:223–230Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Townsend LA, Norman RM, Malla AK, Rychlo AD, Ahmed RR: Changes in cognitive functioning following comprehensive treatment for first episode patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res 2002; 113:69–81Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Malla AK, Mittal C, Lee M, Scholten DJ, Assis L, Norman RM: Computed tomography of the brain morphology of patients with first-episode schizophrenic psychosis. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2002; 27:350–358Medline, Google Scholar

38. Fannon D, Chitnis X, Doku V, Tennakoon L, Ó’Ceallaigh S, Soni W, Sumich A, Lowe J, Santamaria M, Sharma T: Features of structural brain abnormality detected in first-episode psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1829–1834Link, Google Scholar

39. Verdoux H, Bergey C, Assens F, Abalan F, Gonzales B, Pauillac P, Fournet O, Liraud F, Beaussier JP, Gaussares C, Etchegaray B, Bourgeois M, van Os J: Prediction of duration of psychosis before first admission. Eur Psychiatry 1998; 13:346–352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Lieberman JA, Phillips M, Gu H, Stroup S, Zhang P, Kong L, Ji Z, Koch G, Hamer RM: Atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in treatment-naive first-episode schizophrenia: a 52-week randomized trial of clozapine vs chlorpromazine. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28:995–1003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Ring N, Tantam D, Montague L, Newby D, Black D, Morris J: Gender differences in the incidence of definite schizophrenia and atypical psychosis—focus on negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 84:489–496Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Huber G: The heterogeneous course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1997; 28:177–185Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Larsen TK, McGlashan TH, Moe LC: First-episode schizophrenia, I: early course parameters. Schizophr Bull 1996; 22:241–256Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Rabiner CJ, Wegner JT, Kane JM: Outcome study of first-episode psychosis, I: relapse rates after 1 year. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:1155–1158Link, Google Scholar

45. Black K, Peters L, Rui Q, Milliken H, Whitehorn D, Kopala LC: Duration of untreated psychosis predicts treatment outcome in an early psychosis program. Schizophr Res 2001; 47:215–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Haas GL, Sweeney JA: Premorbid and onset features of first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18:373–386Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Ucok A, Polat A, Genc A, Cakiotar S, Turan N: Duration of untreated psychosis may predict acute treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res 2004; 38:163–168Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Kalla O, Aaltonen J, Wahlstrom J, Lehtinen V, Garcia Cabeza I, Gonzalez de Chavez M: Duration of untreated psychosis and its correlates in first-episode psychosis in Finland and Spain. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002; 106:265–275Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Kua J, Wong KE, Kua EH, Tsoi WF: A 20-year follow-up study on schizophrenia in Singapore. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2003; 108:118–125Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. de Haan L, Linszen DH, Lenior ME, de Win ED, Gorsira R: Duration of untreated psychosis and outcome of schizophrenia: delay in intensive psychosocial treatment versus delay in treatment with antipsychotic medication. Schizophr Bull 2003; 29:341–348Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Hafner H, Riecher-Rossler A, Hambrecht M, Maurer K, Meissner S, Schmidtke A, Fatkenheuer B, Loffler W, van der Heiden W: IRAOS: an instrument for the assessment of onset and early course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1992; 6:209–223Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. McGorry PD, Singh BS, Copolov DL, Kaplan I, Dossetor CR, Van Riel RJ: Royal Park Multidiagnostic Instrument for Psychosis, part II: development, reliability, and validity. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16:517–536Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:766–771Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13:261–276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Fahndrich E, Stieglitz RD: Das AMDP System: Manual zur Dokumentation psychiatrischer Befunde, 6th Ed. Gottingen, Germany, Hogrefe, 1997Google Scholar

56. Wing JK, Cooper JE, Sartorius N: The Measurement and Classification of Psychiatric Symptoms. London, Cambridge University Press, 1974Google Scholar

57. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1983Google Scholar

58. Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1983Google Scholar

59. Nuechterlein GK, Subotnik KL, Ventura J, Mintz J, Fogelson DL, Bartzokis G, Aravagiri M: Clinical outcome following neuroleptic discontinuation in patients with remitted recent-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1835–1842Link, Google Scholar

60. Verdoux H, Lengronne J, Liraud F, Gonzales B, Assens F, Abalan F, van Os J: Medication adherence in psychosis: predictors and impact on outcome: a 2-year follow-up of first-admitted subjects. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 102:203–210Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Coldham EL, Addington J, Addington D: Medication adherence of individuals with a first episode of psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002; 106:286–290Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Larsen TK, Johannessen JO, Opjordsmoen S: First-episode schizophrenia with long duration of untreated psychosis: pathways to care. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998; 172:45–52Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Loebel AD, Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, Mayerhoff DI, Geisler SH, Szymanski SR: Duration of psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1183–1188Link, Google Scholar

64. Haas GL, Garratt LS, Sweeney JA: Delay to first antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: impact on symptomatology and clinical course of illness. J Psychiatr Res 1998; 32:151–159Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65. Larsen JK, Johannessen JO, Guldberg CA, Opjordsmoen S, Vaglum P, McGlashan TH: Early intervention programs in first-episode psychosis and reduction of duration of untreated psychosis. Schizophr Res 2000; 36:344–345Google Scholar

66. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Alvir JMJ, Geisler S, Koreen A, Sheitman B, Chakos M, Mayerhoff D, Bilder R, Goldman R, Lieberman JA: Predictors of treatment response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:544–549Link, Google Scholar

67. Harrison G, Croudace T, Mason P, Glazebrook C, Medley I: Predicting the long-term outcome of schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1996; 26:697–705Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68. Moller P: Duration of untreated psychosis: are we ignoring the mode of initial development? an extensive naturalistic case study of phenomenal continuity in first-episode schizophrenia. Psychopathology 2001; 34:8–14Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69. Madsen AL, Vorstrup S, Rubin P, Larsen JK, Hemmingsen R: Neurological abnormalities in schizophrenic patients: a prospective follow-up study 5 years after first admission. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999; 100:119–125Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70. Weinberger DR, McClure RK: Neurotoxicity, neuroplasticity, and magnetic resonance imaging morphometry: what is happening in the schizophrenic brain? Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:553–558Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, Bilder RM, Hinrichsen GA, Lieberman JA: Predictors of medication discontinuation by patients with first-episode schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr Res 2002; 57:209–219Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

72. Ran MS, Xiang MZ, Li SX, Shan YH, Huang MS, Li SG, Liu ZR, Chen EY, Chan CL: Prevalence and course of schizophrenia in a Chinese rural area. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2003; 37:452–457Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

73. Cahn W, Pol HE, Lems EB, van Haren NE, Schnack HG, van der Linden JA, Schothorst PF, van Engeland H, Kahn RS: Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:1002–1010Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

74. Lieberman J, Chakos M, Wu H, Alvir J, Hoffman E, Robinson D, Bilder R: Longitudinal study of brain morphology in first episode schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 49:487–499Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

75. Ho B-C, Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P, Arndt S, Magnotta V, Flaum M: Progressive structural brain abnormalities and their relationship to clinical outcome: a longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study early in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:585–594Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

76. Lieberman JA, Fenton WS: Delayed detection of psychosis: causes, consequences, and effect on public health. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1727–1730Link, Google Scholar

77. Lincoln C, Harrigan S, McGorry PD: Understanding the topography of the early psychosis pathways: an opportunity to reduce delays in treatment. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1998; 172:21–25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

78. Skeate A, Jackson C, Birchwood M, Jones C: Duration of untreated psychosis and pathways to care in first-episode psychosis: investigation of help-seeking behaviour in primary care. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 2002; 43:S73-S77Google Scholar

79. Addington J, van Mastrigt S, Hutchinson J, Addington D: Pathways to care: help seeking behaviour in first episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002; 106:358–364Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

80. Marquis S, Moore MM, Howieson DB, Sexton G, Payami H, Kaye JA, Camicioli R: Independent predictors of cognitive decline in healthy elderly persons. Arch Neurol 2002; 59:601–606Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

81. Lieberman JA: Pathophysiologic mechanisms in the pathogenesis and clinical course of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60(suppl 12):9–12Google Scholar

82. Pantelis C, Velakoulis D, McGorry PD, Wood SJ, Suckling J, Phillips LJ, Yung AR, Bullmore ET, Brewer W, Soulsby B, Desmond P, McGuire PK: Neuroanatomical abnormalities before and after onset of psychosis: a cross-sectional and longitudinal MRI comparison. Lancet 2003; 361:281–288Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

83. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, McMeniman M, Mendelowitz A, Bilder RM: Symptomatic and functional recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:473–479Link, Google Scholar

84. McGorry PD: Evaluating the importance of reducing the duration of untreated psychosis. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2000; 34(suppl):S145-S149Google Scholar

85. Lieberman JA: Is schizophrenia a neurodegenerative disorder? a clinical and neurobiological perspective. Biol Psychiatry 1999; 46:729–739Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

86. Margolis RL, Chuang DM, Post RM: Programmed cell death: implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 35:946–956Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

87. Fuller R, Nopoulos P, Arndt S, O’Leary D, Ho B-C, Andreasen NC: Longitudinal assessment of premorbid cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia through examination of standardized scholastic test performance. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1183–1189Link, Google Scholar

88. Ang YG, Tan HY: Academic deterioration prior to first episode schizophrenia in young Singaporean males. Psychiatry Res 2004; 121:303–307Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

89. Waddington JL, Youssef HA, Kinsella A: Sequential cross-sectional and 10-year prospective study of severe negative symptoms in relation to duration of initially untreated psychosis in chronic schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1995; 25:849–857Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar