Comorbid Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Impact on Treatment Outcome for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study tested the effect of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on behavior therapy outcome for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). METHOD: Subjects were 15 patients with treatment-refractory OCD who were admitted consecutively to a short-term residential facility. Eight met DSM-IV criteria for comorbid PTSD. Patients participated in coached and self-directed behavior treatments of exposure and response prevention as well as in group treatments targeting specific OCD symptoms and related difficulties. Severity of OCD and depression were assessed at admission and exit. RESULTS: Patients with comorbid PTSD showed no significant improvements in OCD and depression symptoms. OCD and depression symptoms improved significantly more in patients without comorbid PTSD than in patients with comorbid PTSD. CONCLUSIONS: Behavioral treatment (with or without medication) of OCD may be adversely affected by the presence of comorbid PTSD.

The impact of diagnostic comorbidity on the outcome of behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is not entirely clear. Some studies have found that personality disorders (1), particularly schizotypal personality disorder (2), negatively affect treatment outcome for OCD, but others have not found such an impact (3). Similarly, a negative effect of depression on treatment outcome for OCD has been demonstrated in some studies (3) but not in others (4).

Recently, two case reports suggested that trauma may play an etiological role in some cases of OCD and that a link may exist between OCD and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and diagnoses (5, 6). However, to our knowledge, the impact of comorbid PTSD on treatment outcome for OCD has not been systematically studied. The current unblinded naturalistic treatment study was conducted to address this issue.

Method

The subjects were 15 patients admitted consecutively to the Massachusetts General Hospital OCD Institute in Belmont, Mass., a short-term residential treatment facility for patients with OCD for whom previous trials of behavior therapy and/or medication had failed. Although pharmacotherapy is an integral component of treatment, the primary emphasis at the OCD Institute is on the behavioral treatments of exposure and response prevention, which have been demonstrated to be effective in numerous studies (7). Daily treatment at the OCD Institute includes 2 hours of coached and 2 hours of self-directed exposure and response prevention sessions in addition to attendance at therapy groups targeting particular OCD symptoms (e.g., violent thoughts, symmetry) and related difficulties (e.g., affect management). Previous trials of behavior and pharmacological therapy administered at other facilities had failed for all 15 patients, and their OCD was considered treatment refractory. Of these 15 patients, eight met DSM-IV criteria for comorbid PTSD, and seven did not. All patients arrive at the OCD Institute already taking a variety of psychotropic medications, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and benzodiazepines. Some patients in the study received dose or drug changes after admittance to the program, but similar changes were made for the patients with comorbid PTSD and those without comorbid PTSD.

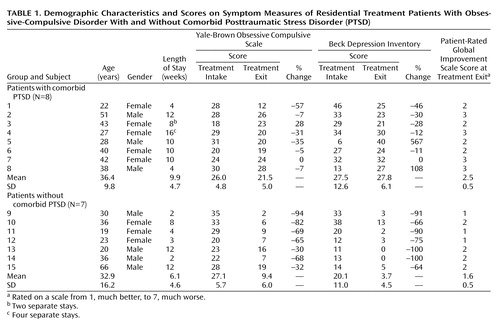

Average length of stay at the OCD Institute was not significantly different between the OCD patients with comorbid PTSD (mean=9.9 weeks, SD=4.7) and OCD patients without comorbid PTSD (mean=6.1 weeks, SD=4.6) (U=16, p=0.18) (Table 1). Additional comorbid diagnoses in the patients with OCD and comorbid PTSD were body dysmorphic disorder and social phobia (subject 2), major depressive disorder and borderline personality disorder (subject 4), major depressive disorder (subject 6), and major depressive disorder and eating disorder not otherwise specified (subject 7). Additional comorbid diagnoses in the patients with OCD who did not have comorbid PTSD were social phobia and dependent and avoidant personality disorders (subject 10), bipolar disorder and eating disorder not otherwise specified (subject 12), dysthymic disorder (subject 13), and body dysmorphic disorder (subject 14). (Information about the types of traumas experienced by the patients in this study is available from the first author.)

As part of routine clinical procedure, all patients completed a battery of questionnaires before admission and received a semistructured diagnostic interview conducted by a psychologist after admission. The intake questionnaires included the Traumatic Events Scale—Lifetime (8), Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (9), Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (10), and Beck Depression Inventory (11). At exit, the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory were administered again, and patients completed the Patient-Rated Global Improvement Scale (12). Because of the small size of the study groups, the significance of differences between groups was assessed with the Mann-Whitney U test, and the significance of change within groups was assessed with the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed ranks test.

Results

Patients with comorbid PTSD did not differ significantly from those without comorbid PTSD in intake OCD severity scores (U=25, p=0.75) or depression severity scores (U=20, p=0.38) (Table 1). (Although test statistics were computed from simple change scores, the percent change in scores is also presented in Table 1 for clinical utility.) When symptom improvement was assessed as simple change from intake (i.e., baseline) to end of treatment (i.e., exit), there were significantly larger improvements for the patients who did not have comorbid PTSD than for the patients with comorbid PTSD on both OCD severity (U=7.5, p=0.02), depression severity (U=7, p=0.02), and subjective perception of improvement at exit (U=8, p=0.02). All patients with OCD who did not have comorbid PTSD showed significant improvement in their OCD (z=2.37, p=0.02) and depression symptoms (z=2.37, p=0.02). As a group, the patients with OCD and comorbid PTSD did not show significant improvement in their OCD symptoms (z=1.69, p=0.09) or depression symptoms (z=0.34, p=0.74). As Table 1 shows, some patients with OCD and comorbid PTSD showed improvements while others exhibited no change or a worsening of symptoms.

Discussion

Although all patients in this study had a diagnosis of treatment-refractory OCD at admission, all patients who did not meet criteria for comorbid PTSD showed significant improvements in OCD and depression severity, with the magnitude of gains similar to those reported in other outcome studies for OCD (13). In contrast, on average, patients who met criteria for comorbid PTSD responded less well to intensive behavior therapy. At best, the symptoms of OCD patients with comorbid PTSD abated somewhat or remained the same; at worst, their symptoms increased in frequency and intensity. Hence, behavioral treatment of OCD (with or without medication) may be adversely affected by the presence of comorbid PTSD and indeed may be contraindicated for some patients.

It was unclear why comorbid PTSD hindered treatment of OCD in some patients (i.e., subjects 6, 7, and 8). However, for others (i.e., subjects 2, 3, 4, and 5), the negative impact of PTSD on OCD treatment outcome was more apparent: initial decreases in OCD symptoms during intensive exposure and response prevention treatment were followed by intensification of trauma-related intrusive thoughts, flashbacks, and nightmares. OCD symptoms then increased in intensity and frequency, seemingly in response. For example, during and after imaginal exposure treatment for violent and sexual obsessions, subject 4 experienced flashbacks related to childhood physical and sexual abuse as well as more frequent and severe nightmares. As a result, she did not habituate to the violent and sexual obsessions, and she experienced an increase in other OCD symptoms, such as feelings of contamination or “dirtiness,” for which she needed to shower several times a day. Similarly, during and after exposure and response prevention to address fears and rituals related to knives and harming others, subject 2 experienced flashbacks related to his combat experiences, which in turn reintensified some checking rituals (e.g., checking to make sure he’d walked through a doorway in exactly the right way so as not to harm someone).

Thus, for some of the OCD patients with comorbid PTSD, their OCD symptoms appeared inextricably tied to their traumatic experiences and comorbid PTSD symptoms. A similar phenomenon has been referred to as “posttraumatic OCD” (6). For these patients, OCD symptoms may serve as a coping function (by means of avoidance) against psychologically painful trauma-related thoughts and images. It has been speculated previously that the avoidance/numbing symptoms of PTSD may alternate with the arousal symptoms of PTSD (14). Similarly, in some OCD patients with comorbid PTSD, OCD rituals may alternate with PTSD symptoms, with decreases in one leading to increases in the other and vice versa. Taken together, these findings suggest that treatment for OCD should be combined with systematic treatment for PTSD when this comorbid condition is present. For example, cognitive behavior approaches, such as stress inoculation training and prolonged imaginal exposure to trauma-related memories, and psychopharmacological approaches, such as the administration of particular types of SSRIs and neuroleptic medications, have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of PTSD (15) and may provide a beneficial adjunct in the treatment of these patients. The effectiveness of such combined treatment awaits further study.

|

Received June 13, 2001; revision received Dec. 4, 2001; accepted Jan. 15, 2002. From Massachusetts General Hospital and the Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School. Address reprint requests to Dr. Gershuny, Massachusetts General Hospital East, OCD Clinic and Research Unit, 9th Fl., Bldg. 149, 13th St., Charlestown, MA 02129; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by a grant to Dr. Gershuny from the Obsessive-Compulsive Foundation. The authors thank Dr. Edna B. Foa for comments on the manuscript.

1. AuBuchon PG, Malatesta VJ: Obsessive compulsive patients with comorbid personality disorder: associated problems and response to a comprehensive behavior therapy. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:448-453Medline, Google Scholar

2. Minichiello WE, Baer L, Jenike MA: Schizotypal personality disorder: a poor prognostic indicator for behavior therapy in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord 1987; 1:273-276Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Steketee G, Chambless DL, Tran GQ: Effects of axis I and II comorbidity on behavior therapy outcome for obsessive-compulsive disorder and agoraphobia. Compr Psychiatry 2001; 42:76-86Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Zitterl W, Demal U, Aigner M, Lenz G, Urban C, Zapotoczky HG, Zitterl-Eglseer K: Naturalistic course of obsessive compulsive disorder and comorbid depression: longitudinal results of a prospective follow-up study of 74 actively treated patients. Psychopathology 2000; 33:75-80Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. DeSilva P, Marks M: The role of traumatic experiences in the genesis of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther 1999; 37:941-951Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Pitman RK: Posttraumatic obsessive-compulsive disorder: a case study. Compr Psychiatry 1993; 34:102-107Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Foa EB, Franklin ME: Psychotherapies for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review, in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Edited by Maj M, Sartorius N, Okasha A, Zohar J. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 2000, pp 93-115Google Scholar

8. Gershuny BS: Traumatic Events Scale—Lifetime. Kansas City, University of Missouri, Department of Psychology, 1999Google Scholar

9. Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K: The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychol Assess 1997; 9:445-451Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, Heninger GR, Charney DS: The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale, I: development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:1006-1011Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Beck AT, Steer RA: Manual for the Revised Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1987Google Scholar

12. Baer L, Rauch SL, Ballantine HT, Martuza R, Cosgrove R, Cassem E, Giriunas I, Manzo PA, Dimino C, Jenike MA: Cingulotomy for intractable obsessive-compulsive disorder: prospective long-term follow-up of 18 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:384-392Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Franklin ME, Abramowitz JS, Kozak MJ, Levitt JT, Foa EB: Effectiveness of exposure and ritual prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: randomized compared with nonrandomized samples. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 68:594-602Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Foa EB, Riggs DS, Gershuny BS: Arousal, numbing, and intrusion: symptom structure of PTSD following assault. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:116-120Link, Google Scholar

15. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ (eds): Effective Treatments for PTSD. New York, Guilford, 2000Google Scholar