Methods to Improve Diagnostic Accuracy in a Community Mental Health Setting

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study determined the extent to which adding structured procedures improved diagnostic accuracy for outpatients with severe mental illness in a community mental health setting. METHOD: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) was used to interview 200 psychiatric outpatients. A research nurse reviewed medical records and amended the SCID diagnoses accordingly. A research psychiatrist or psychologist reviewed the diagnostic data and interviewed each patient to verify or further modify the previous findings. Diagnostic outcomes at each step of the procedure were compared to determine whether adding additional data improved diagnostic accuracy. The additional time required for each element of the diagnostic procedure was also assessed. RESULTS: Kappa comparisons of the different diagnostic levels showed that adding additional data significantly improved accuracy. Diagnoses rendered by combining the SCID and review of the medical record were the most accurate, followed by the SCID alone, and then diagnoses made by psychiatrists during routine care. In addition, the SCID alone identified five times as many current and past secondary diagnoses as were documented routinely in patients’ charts. CONCLUSIONS: Combining structured interviewing with a review of the medical record appears to produce more accurate primary diagnoses and to identify more secondary diagnoses than routine clinical methods. The patients’ knowledge of their diagnoses was limited, suggesting a need for patient education in this setting. Whether use of structured interviewing in routine practice improves patient outcomes deserves further study.

Psychiatrists are primarily responsible for rendering diagnoses that guide medication selection for the severely mentally ill. Although treatment plans are often based on symptoms rather than diagnostic type, the advent of disease-specific treatment protocols has heightened the necessity for accurate diagnostic procedures. Unfortunately, evaluating symptoms, prior course of illness, and general medical, family, and treatment histories, although essential for obtaining accurate diagnoses (1), is both time consuming and costly, and it is unclear how much of this information is needed to ensure the accuracy of psychiatric diagnoses.

The expansion of the role of psychiatric nurses and other nonphysician mental health professionals to include assistance in acquiring diagnostic information may help to streamline, reduce costs, and improve the thoroughness and accuracy of psychiatric diagnoses. However, the acceptance of these efforts from nonphysician personnel by the medical profession hinges on evidence of their accuracy as well as their clinical utility. In community mental health settings, the additional costs in clinician time must be compared to the improved accuracy afforded to determine whether it is cost-effective to implement these additional procedures in particular treatment settings.

To improve diagnostic accuracy, several structured clinical interviews, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (2) and the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (3), have been created and tested. Structured diagnostic interviews are superior to less-structured clinical interviews in deriving reliable psychiatric diagnoses (4–12) because they facilitate symptom reporting while systematically probing symptoms and behaviors that clinicians may overlook (13, 14), hence reducing variability (15).

While the SCID has been most frequently used as a research tool (16), its utility in clinical practice has not been widely evaluated. To be useful to mental health centers where resources are limited and the demand for services is great, structured interviews must improve diagnostic accuracy and meaningfully add to the diagnostic information provided by usual practices to justify the increased time, effort, and cost.

In an exploration of this question, 200 outpatients were asked to report their diagnoses and were interviewed with the SCID and supplementary diagnostic measures by trained psychiatric nurses. After determining the SCID-generated diagnoses, the nurses carefully reviewed each medical record and revised the SCID diagnoses as needed on the basis of these additional data. After review of these modified diagnoses as well as the SCID and the medical record, a research psychiatrist or psychologist with diagnostic expertise briefly interviewed each patient to clarify diagnostic questions and render a final diagnosis, which served as the “gold standard.” These diagnoses were then compared to the diagnoses generated at each step in the diagnostic process. The time required to complete each element in the assessment process was monitored and recorded to help evaluate the relative advantages and feasibility of making use of each step in the diagnostic procedure.

Method

Over 18 months, 210 subjects were recruited from a community mental health center through in-clinic advertisements offering free diagnostic evaluations and through clinician referrals. For 2 months before the beginning of subject recruitment, the researchers met with the clinic staff to discuss the study protocol and designed recruitment procedures that minimized interference with clinic activities. The study was introduced to patients and staff as a test of the degree to which the diagnostic procedures used in research protocols would be useful in a community mental health clinic.

Each subject signed an informed consent statement before study participation. The subject was paid $20 upon completion of both the initial diagnostic interview and a follow-up interview with the research psychiatrist or psychologist. Approximately 30% of the subjects volunteered after seeing study advertisements, 41% were referred by psychiatrists, 20% were referred by caseworkers, and 9% were referred by other clinic staff. A total of 200 subjects, 84 men (42%) and 116 women (58%), completed both interviews and were included in the analyses. All subjects were between 18 and 76 years of age (mean=37.6, SD=10). Two-thirds of the subjects (67%) were Caucasian (N=134), 20% were African American (N=39), 12% were Hispanic (N=23), 1% were Asian American (N=2), and 1% belonged to other racial groups (N=2). Only 19% were married (N=37).

Procedures

The study subjects completed a demographic questionnaire, including self-report of diagnosis, and participated in a diagnostic interview with one of three trained psychiatric nurses (including D.D. and V.B.). The diagnostic interview included 1) the SCID (outpatient version), 2) family history of psychiatric illness, and 3) general medical history. For each patient, a life chart (17) was constructed from the information gathered during the diagnostic interview. The life chart is a graphic representation of an individual’s course of illness across time. The information documented on the life chart included episodes of illness, periods of treatment (including hospitalizations), and significant life events. After the diagnostic interview, the nurse evaluators followed the SCID diagnostic algorithm and documented the resulting diagnoses as well as the length of time it took to administer the SCID. These data are referred to as the “SCID diagnoses” in the analyses.

Medical Record Review

After administering the SCID, the nurse evaluators reviewed the patients’ medical records, including progress reports, physician orders, hospital admission and discharge summaries, and summaries of emergency room visits. Of interest was information that supported, conflicted with, or expanded on the information provided during the SCID, including prior diagnoses. After completion of the record review, diagnoses that integrated information from the SCID and the medical record were documented. These diagnoses are referred to as “SCID-plus-chart diagnoses.” The time needed to review the medical record was also recorded.

Diagnoses rendered during routine care were made at initial clinic intake by a psychiatrist who interviewed the patient and entered the diagnosis in the medical chart. Typically, the routine diagnoses were rendered after a 40–45-minute interview by the psychiatrist, usually without an informant who knew the patient well and often without access to prior medical records. The routine diagnoses were reviewed and updated every 2 years by the treating psychiatrist. During the chart review, the patient’s most recent diagnosis rendered by the treating psychiatrist was documented. These are referred to as “routine diagnoses.”

Follow-Up Interview

Approximately 1 week after administration of the SCID, each patient returned for a follow-up interview by one of three study psychiatrists (including J.Q.B. and W.H.) or a psychologist (M.R.B.) trained in diagnostic procedures, to assess the accuracy of the SCID-plus-chart diagnoses. Before this interview the psychiatrist/psychologist reviewed the SCID, the medical and family histories, the life chart, and the medical record. During the follow-up interview the clinician reviewed the DSM-III-R criteria for the SCID-plus-chart diagnoses and determined the presence of any possible differential diagnoses or concurrent psychiatric problems not previously identified. Since the SCID did not cover all diagnostic possibilities, a skilled diagnostician was needed to consider a broader range of possible disorders, including axis II disorders. At the completion of the follow-up interview, the research clinician rendered a diagnosis. These are referred to as the “gold standard diagnoses.” The length of the follow-up interviews was recorded.

Results

Diagnostic Agreement

To evaluate the accuracy of diagnoses, we calculated kappa reliability coefficients (18) to compare the gold standard diagnoses to the routine diagnoses, SCID diagnoses, and SCID-plus-chart diagnoses, respectively. Kappa coefficients represent the amount of agreement between pairs of ratings (e.g., agreement on a diagnosis five out of 10 times) adjusted for chance agreement. Chance is based on the likelihood that a specific diagnosis will occur in a sample. For example, if in a sample of 100 patients, 50 have a diagnosis of schizophrenia, a rater is going to be correct at least 50% of the time if he or she arbitrarily gives everybody a diagnosis of schizophrenia. When the base rate of a specific diagnosis is high in a sample of patients, the chance of being accurate in giving that diagnosis will also be high. Kappa subtracts the percentage of agreement (agreements divided by the total number of comparisons) from the probability of agreement by chance. This offers a less biased estimate of agreement.

The comparisons of the gold standard and the other diagnoses were conducted at three levels of diagnostic specificity. Level 1 was the most specific, and level 3 was the least specific. Level 1 required that the gold standard diagnosis match exactly with the others on core diagnosis (e.g., bipolar disorder) but not the subtype (e.g., most recent episode manic, depressed, or mixed). It was not required that the diagnoses match on whether the major depressive disorder was a single episode or recurrent, on the specific subtype of schizophrenia, on the specific drug type in substance abuse, or on the symptom or feature type for organic mental disorders or adjustment disorders. In addition, discriminations between substance abuse and dependence were not required at level 1.

At level 2, diagnoses that shared symptoms, and therefore could be easily confused with one another, were grouped together (i.e., less precision in diagnosis was required). Major depressive disorder, depression not otherwise specified, and dysthymia were grouped together as depressive disorders. Bipolar disorders (I, II, and not otherwise specified) and cyclothymia constituted a second grouping. Generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder, and social phobia were combined under anxiety disorders. All other diagnoses were grouped the same as for level 1. At this second level of analysis, diagnoses were considered in agreement if they fell within a grouping. For example, panic disorder and OCD were considered a match at level 2, just as major depressive disorder and dysthymia were considered a match at level 2.

At level 3, more global categories were created, requiring even less precision in diagnoses than at level 2. Depressive disorders and bipolar disorders were grouped together under mood disorders. All psychotic disorders were grouped together with the exception of schizoaffective disorder, which stood alone. All other groupings were the same as for level 2. To be considered a match, agreement only within the broad diagnostic groupings was required. For example, major depressive disorder and bipolar I disorder were considered a match at level 3, just as schizophrenia and delusional disorder were considered a match at level 3.

A comparison of gold standard diagnoses with the clinic psychiatrists’ routine diagnoses based on standard interview practices revealed levels of agreement for the total sample as follows: level 1, kappa=0.45; level 2, kappa=0.51; and level 3, kappa=0.52. As less precision was required, the amount of agreement between diagnoses increased. In an examination of kappa coefficients for subsamples of diagnostic groups containing at least nine patients, the routine diagnoses were most accurate for schizophrenia, which had kappa values from 0.59 to 0.69, and least accurate for schizoaffective disorder, with a kappa of 0.46 across levels 1–3.

In the comparison of the gold standard to the diagnoses derived by the study nurses using the SCID only, the kappa reliability coefficients for the total sample were 0.61 (level 1), 0.64 (level 2), and 0.64 (level 3). SCID diagnoses were also most accurate for schizophrenia, with a kappa of 0.72, and least accurate for schizoaffective disorder, with a kappa of 0.57.

To assess the relative importance of adding the medical record review to the diagnostic process, kappa coefficients were calculated for the comparison of the SCID-plus-chart diagnoses to the gold standard diagnoses. The kappa values were 0.76 (level 1), 0.76 (level 2), and 0.78 (level 3) for the total sample. The diagnoses were most accurate for schizophrenia, with a kappa of 0.87, and least accurate for depression, with kappas from 0.76 to 0.81 across levels 1–3.

There were no differences in kappa coefficients between male and female patients in any of the comparisons. For the comparison of the gold standard and the SCID-plus-chart diagnoses, there were no differences in kappa values by racial group. For the comparison of the gold standard and routine diagnoses, there were no differences at level 1; however, at levels 2 and 3, the kappa coefficients were lower for Caucasians (0.47 and 0.49, respectively) than for non-Caucasians (0.57 and 0.59, respectively). These differences were not due to differences in group size or in chance agreement.

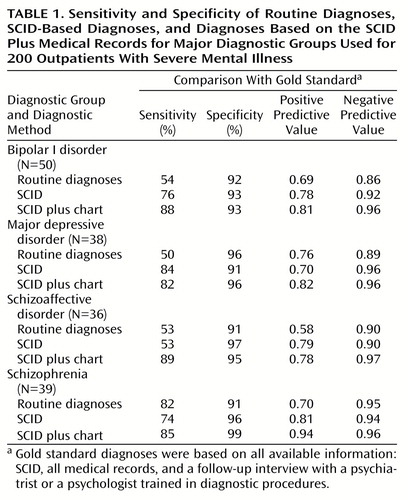

The sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value and negative predictive value for the four major diagnostic groups at each step in the diagnostic process are presented in Table 1. Relative to the gold standard diagnoses, the sensitivity and specificity of the SCID-plus-chart diagnoses were generally superior to those of the routine diagnoses and the SCID alone. In particular, use of the SCID plus medical records substantially improved the detection of mood disorders and schizoaffective disorder over clinic procedures, while maintaining a high level of accuracy. Note that sensitivity and specificity analyses do not adjust for chance agreement and, therefore, inflate performance levels.

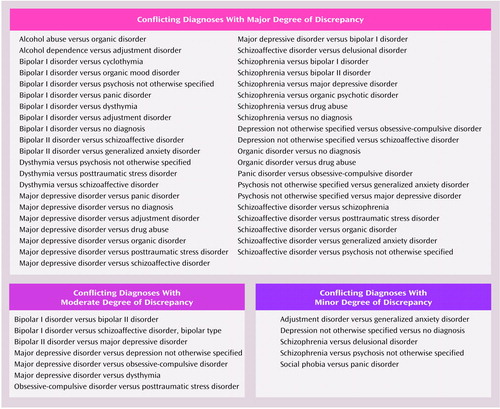

To evaluate the clinical importance of the diagnostic disagreements, each was categorized as a major, moderate, or minor discrepancy (Figure 1). Diagnostic disagreements were defined as major if the differences would imply different pharmacological or psychotherapeutic treatment strategies or different prognoses or would influence the decision to seek additional general medical evaluations. Moderate discrepancies were those in which the treatment indications would not differ as dramatically as for the major category and additional diagnostic workups would not be indicated. Minor discrepancies were those in which treatment plans would not be likely to change much or at all despite diagnostic differences. The majority of the diagnostic differences between the routine diagnoses and the gold standard (64 of 94, 68%), between the SCID and the gold standard (51 of 65, 78%), and between the SCID-plus-chart method and the gold standard (30 of 43, 70%) were considered major discrepancies. Of the remaining diagnostic disagreements, 29% of the routine diagnoses (N=27), 17% of those based on the SCID (N=11), and 23% of those based on the SCID plus medical chart (N=10) were considered moderate discrepancies with the gold standard.

Comorbid Diagnoses

The SCID-plus-chart method identified 223 comorbid diagnoses in the 200 patients; of these, 96 were current and 127 were disorders in remission. Current disorders included alcohol or substance use (41%), anxiety (33%), mood (17%), or other (9%) axis I disorders. Among the routine diagnoses, 41 comorbid disorders were recorded for these same individuals, of which 35 were current and six were in remission. Current disorders included alcohol or substance use (57%), anxiety (11%), mood (14%), and other (17%) axis I disorders.

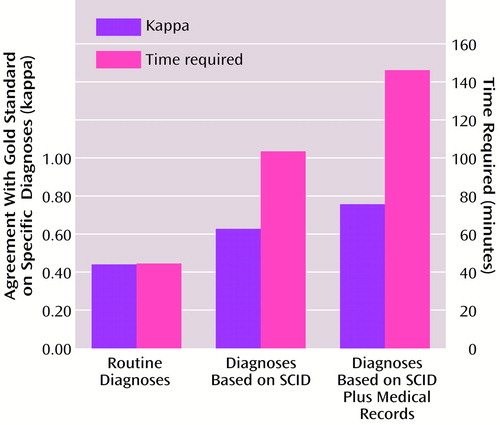

Length of Diagnostic and Follow-Up Interviews

Each step that contributed to the gold standard diagnoses was timed for each patient; these times were averaged across patients. Although we did not acquire similar data for the routine diagnoses, the usual initial intake evaluation by a clinic psychiatrist lasted 45 minutes and followed a 30–45-minute screening interview by an intake worker. On average, the time to administer the SCID and accompanying diagnostic measures (e.g., medical history) was approximately 1 hour and 44 minutes (SD=32.6 minutes). The chart review took an average of 42 minutes (SD=34.0). The average length of the follow-up interview with the study psychiatrist or psychologist to attain the gold standard diagnosis was 40 minutes (SD=18.7). Figure 2 shows a summary of the diagnostic accuracy at each step of the assessment process along with the average amount of time needed to achieve that level of accuracy.

Comparability of Patient and Clinician Diagnoses

In a self-report measure administered before the SCID interview, each patient was asked to respond to the question “What is your diagnosis?” An examination of the patients’ diagnostic impressions showed that 44% of them (N=88) reported diagnoses that matched the routine diagnoses rendered by their clinic psychiatrists. The others either did not know their diagnoses (26%, N=52) or were incorrect (30%, N=60). A chi-square comparison of patient response by level 2 diagnostic group (χ2=103.94, df=36, p<0.0001) showed that the patients with bipolar disorder or cyclothymia were most likely to know the diagnoses assigned to them by their clinic psychiatrists. Patients with depressive disorders or schizophrenia were most likely to report that they did not know their diagnoses, while patients with schizoaffective disorder were most likely to be incorrect about their diagnoses.

Acceptance of SCID Diagnoses by Clinic Psychiatrists

It was not the intent of this study to evaluate the impact of the diagnostic process on patient care. Therefore, feedback was not provided to the clinic psychiatrists unless specifically requested by patients or physicians. However, most physicians and patients did, in fact, request information. In these cases, progress notes documenting the diagnoses were placed in the patients’ charts. When the gold standard diagnosis differed from the routine diagnosis, an explanation for the diagnostic difference was provided. Feedback was provided to clinic psychiatrists for 72% of the 200 patients evaluated (N=143). In one-half of the cases the gold standard and routine diagnoses were in disagreement.

One month after feedback was provided, the medical records of each of these 143 patients were reviewed to determine whether any changes in treatment had occurred. In one-half of the cases, feedback led to a change in patient care. For example, a change in diagnosis and/or treatment was documented in 57 charts. Additional testing for potential general medical conditions as possible sources of psychiatric symptoms was ordered for four patients, additional patient education was provided for seven, and referral to additional support or vocational services was provided for three patients. Without a control group, it is difficult to determine whether these changes were a direct result of providing diagnostic feedback or a naturally occurring pattern of patient care.

Discussion

In this group of patients, each added step in the diagnostic process improved the agreement with the gold standard. The kappa coefficients showed that administration of the SCID without the benefit of the medical record improved accuracy over that achieved with routine diagnoses, while adding information derived from the record review resulted in an additional 25% improvement in diagnostic accuracy over that with the SCID alone. These findings are consistent with reports from other studies (6, 7, 9) that have shown distinct advantages of structured diagnostic interviews over unstructured clinical interviews. However, a kappa of 0.76 (SCID-plus-chart diagnoses), while excellent, suggests that without the supervision of a trained diagnostician, structured assessment methods are less than perfect.

The percentage of agreements (not adjusted for chance) with the gold standard were 53% for routine diagnoses, 68% for the SCID, and 79% for the SCID plus chart review. In all three groups, when discrepancies occurred, most were of substantial clinical importance. Furthermore, a large number of concurrent and past diagnoses with significant implications for treatment selection were identified by the SCID-plus-chart procedure.

When group size was taken into consideration, routine diagnoses were most accurate for schizophrenia. For the SCID, the kappa coefficients were highest for schizophrenia, major depression, alcohol dependence/abuse, and bipolar disorder. In addition to all of the preceding, the SCID-plus-chart method demonstrated high levels of accuracy in detecting schizoaffective disorder. Patients with these five diagnoses (defined by the gold standard) accounted for 82% of the study group.

While not replacing the function of the clinic psychiatrists, the SCID combined with a medical record review can save doctors time when arriving at diagnoses, while also improving accuracy if personnel to conduct SCID interviews are available. Diagnostic procedures and time are reduced. After the SCID, the study psychiatrist/psychologist needed an average of 40 minutes (SD=18.7) to derive a diagnosis that stood as the gold standard. If diagnostic information can be shared across treatment settings (e.g., clinic, emergency room, hospital), the time and cost savings would become greater as costly diagnostic procedures and time are reduced.

Particularly disconcerting is that more than one-half of the patients in this study either did not know or were incorrect about their diagnoses. Patients who are unaware of or have misconceptions about their diagnoses can have problems with treatment compliance (19).

Over the 18 months of this study, referral of patients by the clinic staff, particularly psychiatrists, steadily increased. In one-half of the cases in which feedback on diagnosis was provided to the clinic psychiatrists, changes in treatment strategies occurred within the following month. These two events suggest that the diagnostic methods were accepted by and useful to physicians, although without an appropriate control group, no specific conclusions can be drawn.

There are some limitations to the generalizability of these findings to the community mental health center population as a whole. The subjects were not randomly selected, although their gender and racial distributions were generally similar to those of the entire clinic. The study group included a smaller proportion of subjects with schizophrenia (22.5% versus 37.4% as defined by the clinic psychiatrists), a larger representation of patients with bipolar disorder (19.5% versus 15.5%), and a smaller proportion of patients with major depression (12.5% versus 14.4%). This distribution of study subjects could have produced underestimates of the kappa values for the comparisons of the gold standard to routine diagnoses, given that the latter were most accurate for schizophrenia. However, a larger proportion of patients with schizophrenia in the group would have also elevated the probability of chance agreement in the kappa calculation, perhaps offsetting any gains in percentage agreement.

Of the three nurses who served as evaluators in the study, one had considerable experience in the use of the SCID. She evaluated 22% of the subjects. The other two were recruited from the staff of the community mental health center and had no prior research experience. They were trained in the administration of the SCID by the first nurse and one of us (M.R.B.) through didactics and an apprenticeship for approximately 6 weeks before participating in this study. These nurses were not selected at random from the nursing staff and therefore may not represent the skill level of the average clinic nurse.

The study psychologist and psychiatrists were trained in diagnostic assessment, including the use of the SCID and other structured diagnostic methods. They had access to the SCID findings before the follow-up interview, which could have increased agreement between the gold standard and the SCID. However, the kappa values for the comparison of the gold standard to the SCID-plus-chart diagnoses were comparable to, although perhaps slightly lower than, those found in other studies (7) evaluating the performance of the SCID when used by independent raters (i.e., those without access to the SCID findings), arguing against bias in the diagnoses. Perhaps any advantages of access to the SCID diagnoses was offset by the advantage to the clinic psychiatrists of having had many opportunities to observe patients in both more and less symptomatic states.

The implications of this study for managers of service systems are significant. Accurate diagnoses are important both for the proper selection of treatments and for estimation of treatment or insurance costs. In addition, educating patients about their illness obviously must be based on an accurate diagnosis as well. Use of the SCID may not be the only method for achieving a more thorough and accurate diagnostic workup. However, these results do suggest that “routine” practice in a busy public sector clinic—even if it entails only a 40-minute evaluation (all interview, chart review, and record-keeping time by the psychiatrist) of severely ill patients—may be insufficient for up to one-half of the population. Further, psychiatrist time and staff support/assistance in acquiring diagnostic information would appear on the basis of the present results to change diagnoses to a clinically significant degree for many patients (i.e., many of the revised diagnoses were incorporated into patient care by the physician). Thus, inasmuch as nonphysician assistants help to gather historical and physical examination evidence to inform the general medical diagnoses, similar efforts may be helpful in rendering psychiatric diagnoses.

In sum, given the large array of available and effective treatments for individuals with mental illnesses, accurate diagnoses are clearly important, as they assist practitioners in matching treatments to disorders (20). The current technology and procedures commonly used in clinical research to obtain reliable diagnoses can be adapted to community mental health settings. They may be especially helpful in assessing patients with complex clinical presentations, as are often found in these clinics. Administrators must make policy decisions as to whether the added accuracy in diagnosis is worth a change in clinic procedures and perhaps staff responsibilities. Further research is needed to identify the longer-term costs and cost savings of adopting such efforts in community mental health settings.

|

Presented in part at the 7th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, Chicago, Oct. 14–16, 1993. Received March 4, 1996; revisions received Dec. 20, 1996, Nov. 29, 1999, and March 27, 2000; accepted May 30, 2000. From the Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health Connections Research Program, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. Address reprint requests to Dr. Basco, 2930 Central Dr., Bedford, TX 76021; [email protected] (e-mail).Supported in part by Mental Health Connections, a Texas-legislature-funded partnership between the Dallas County Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, and by NIMH grants MH-41115 and MH-53799.The authors thank Jonathan McNorton, Larry Tripp, M.D., and Kenneth Z. Altshuler, M.D., for assistance in the conduct of this study.

Figure 1. Discrepancies Between Gold Standard Diagnosesa and Those Based on Routine Diagnoses, SCID, or SCID Plus Medical Records for 200 Outpatients With Severe Mental Illness

aGold standard diagnoses were based on all available information: SCID, all medical records, and a follow-up interview with a psychiatrist or a psychologist trained in diagnostic procedures.

Figure 2. Time Requirement and Reliability of Routine Diagnoses, SCID-Based Diagnoses, and Diagnoses Based on the SCID Plus Medical Records for 200 Outpatients With Severe Mental Illnessa

aReliability was determined by comparison with diagnoses based on the SCID, all medical records, and a follow-up interview with a psychiatrist or a psychologist trained in diagnostic procedures; these diagnoses were considered the “gold standard.” The comparisons are for specific DSM-III-R diagnoses but not subtypes (level 1 diagnoses).

1.. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for Psychiatric Evaluation of Adults. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152(Nov suppl):63–80Google Scholar

2.. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Instruction Manual for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1989Google Scholar

3.. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS: The National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:381–389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4.. Grove WM, Andreasen NC, McDonald-Scott P, Keller MB, Shapiro RW: Reliability studies of psychiatric diagnosis: theory and practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:408–413Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5.. Keller MB, Lavori PW, McDonald-Scott P, Scheftner WA, Andreasen NC, Shapiro RW, Croughan J: Reliability of lifetime diagnoses and symptoms in patients with a current psychiatric disorder. J Psychiatr Res 1981; 16:229–240Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6.. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Ratcliff KS, Seyfried W: Validity of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, version II: DSM-III diagnoses. Psychol Med 1982; 12:855–870Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7.. Riskind JH, Beck AT, Berchick RJ, Brown G, Steer RA: Reliability of DSM-III diagnoses for major depression and generalized anxiety disorder using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:817–820Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8.. Skre I, Onstad S, Torgersen S, Kringlen E: High interrater reliability for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis I (SCID-I). Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 84:167–173Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9.. Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB, Spitzer RL, Davies M, Borus J, Howes MJ, Kane J, Pope HG, Rounsaville B, Wittchen H-U: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), II: multisite test-retest reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:630–636Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10.. Kranzler HR, Ronald RM, Burleson JA, Babor TF, Apter A, Rounsaville BJ: Validity of psychiatric diagnoses in patients with substance use disorders: is the interview more important than the interviewer? Compr Psychiatry 1995; 36:278–288Google Scholar

11.. Stein MB, Forde DR, Anderson G, Walker JR: Obsessive-compulsive disorder in the community: an epidemiologic survey with clinical reappraisal. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1120–1126Google Scholar

12.. Ventura J, Liberman RP, Green MF, Shaner A, Mintz J: Training and quality assurance with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I/P). Psychiatry Res 1998; 70:163–173Crossref, Google Scholar

13.. Welner A, Liss JL, Robins E: A systematic approach for making a psychiatric diagnosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 31:193–196Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14.. Anthony JC, Folstein M, Romanoski AJ, Von Korff MR, Nestadt GR, Chahal R, Merchant A, Brown CH, Shapiro S, Kramer M, Gruenberg EM: Comparison of the lay Diagnostic Interview Schedule and a standardized psychiatric diagnosis: experience in eastern Baltimore. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:667–675Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15.. Weinstein SR, Stone K, Noam GG, Grimes K, Schwab-Stone M: Comparison of DISC with clinicians’ DSM-III diagnoses in psychiatric inpatients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1989; 28:53–60Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16.. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624–629Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17.. Post RM, Roy-Byrne PP, Uhde TW: Graphic representation of the life course of illness in patients with affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:844–848Link, Google Scholar

18.. Cohen J: A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychol Measurement 1960; 20:37–46Crossref, Google Scholar

19.. Jamison KR, Gerner RH, Goodwin FK: Patient and physician attitudes toward lithium. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:866–869Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20.. Rush AJ, Prien R: From scientific knowledge to the clinical practice of psychopharmacology: can the gap be bridged? Psychopharmacol Bull 1995; 31:7–20Google Scholar