Suicidal Behavior in Patients With Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Patients with schizophrenia are known to be at high risk for suicide attempts and dying by suicide. However, little research has been conducted to determine whether the risk for suicidal behavior is elevated among patients with psychosis in general. METHOD: This study evaluated 1-month and lifetime rates of suicidal behavior among 1,048 consecutively admitted psychiatric inpatients (ages 18 to 55 years) with DSM-III-R psychotic disorders. Demographic, clinical, and diagnostic correlates of suicidal behavior were examined. RESULTS: A high rate of suicidal behavior was found in the group: 30.2% reported a lifetime history of suicide attempts, and 7.2% reported a suicide attempt in the month before admission. The highest 1-month and lifetime rates were found in patients with schizoaffective disorder and major depression with psychotic features. Ratings of the medical dangerousness of the most recent suicide attempt on the basis of the extent of physical injury were higher in patients with schizophrenia spectrum psychoses. Agreement was high between emergency room assessments and semistructured interview assessments of suicidal behavior. CONCLUSIONS: Rates of suicidal behavior were high across a broad spectrum of patients with psychotic disorders; patients with a history of a current or past major depressive episode (as a part of major depressive disorder or schizoaffective disorder) were at a greater risk for suicide attempts, but patients with schizophrenia, on average, made more medically dangerous attempts. Risk factors for suicidal behavior in patients with psychosis appear to vary compared to those for the general population.

Suicide is the chief cause of premature death among individuals with schizophrenia. Approximately 10% of patients with schizophrenia die by suicide (1–3). Risk factors for suicide in schizophrenia include being young, male, and in the early years of the illness and having a history of multiple previous episodes or previous suicide attempts (4–7). A substantial percentage of patients with schizophrenia also attempt suicide, with estimates of lifetime occurrence ranging from 18% to 55% (8). Between 50% and 80% of suicide attempts do not result in death, but a history of suicide attempts is common in patients with schizophrenia who die by suicide (40% to 61% of cases) (3, 9, 10). The risk of dying by suicide in patients with psychosis is also increased by the presence of depression (11, 12). Conversely, evidence for an association between psychosis and suicide among individuals with depression has been equivocal (13–15).

Only one previous study involving direct interviews has examined the rates of suicidal behavior in a large consecutive series (N=801) of individuals with schizophrenia seeking emergency evaluation and care (16). The authors of that study found a high rate (32%) of current suicidal indicators (death wishes, suicidal plans, and suicide attempts) on admission to the hospital. Subjects with recent suicidal indicators were distinguished from nonsuicidal patients with schizophrenia on three clinical variables: presence of depressive symptoms, history of a previous suicide attempt, and greater impairment in role functioning. That study was restricted to patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Suicidal behavior has not been systematically examined across the broad spectrum of patients with psychotic disorders, irrespective of diagnosis. To our knowledge, the current study represents the first report on the recent and lifetime rates of suicidal behavior in a large clinical study group of consecutively admitted individuals with psychotic disorders. By including patients with all psychotic disorders, we were able to compare rates of suicidal behavior across affective and nonaffective psychoses and to identify demographic and clinical characteristics that distinguished patients with a history of past or recent suicidal behavior. We also examined the relationship of diagnosis to the medical seriousness of suicidal behavior.

METHOD

Subjects

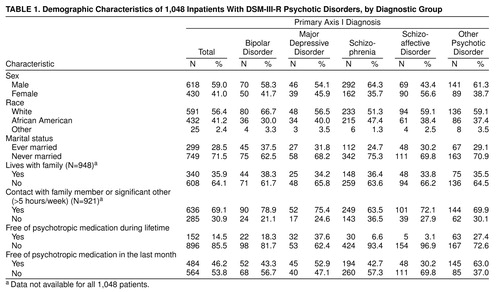

Subjects comprised a nonduplicated, consecutively admitted series of 1,048 psychiatric inpatients with psychotic disorders admitted to the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic/University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, a university-based psychiatric treatment facility. Subjects were admitted between Jan. 1, 1992, and May 1, 1994, and all met the following criteria: 1) age between 15 and 55 years and 2) hospital admission diagnosis of any DSM-III-R psychotic disorder as determined by the admitting psychiatrist. Patients were included in our analyses only once, and if they were readmitted during the study period, only the data from the first admission were included. The diagnostic breakdown for the study group is presented in Table 1. Eighty-four (37% of the 230) patients in the nonschizophrenia, nonaffective psychotic disorder category had a psychotic disorder that was judged to be secondary to current substance abuse/dependence or an organic/medical condition.

Assessment Procedures

On admission to the emergency room, all patients received a psychiatric evaluation by a psychiatric resident or clinician (nurse or social worker), after which patients were evaluated by an attending psychiatrist. This evaluation included a standard clinical semistructured interview designed to gather data about relevant clinical history, current symptoms, and recent and past suicidal ideation and behavior. These data were supplemented by information obtained from clinical records, referring and treating physicians, and interviews with relatives and friends and are representative of the diagnostic information typically available in the context of an initial evaluation of acutely ill psychotic patients in an emergency service.

On the basis of a review of hospital records, a research clinician (E.D.R. or another) recorded data pertaining to the presence of psychosis and suicidal behavior. Suicidal behavior was classified in terms of the following three categories: 1) attempted suicide (self-injurious behavior for which the individual reports the intent to die), 2) ideation about suicide (thoughts about suicide with a wish to die, without suicide attempts), and 3) no attempt/ideation (no suicidal thoughts or attempts). Through use of this classification scheme, each patient was evaluated and assigned both a recent (within 1 month before admission) and a past (1 month or more before admission) classification.

The medical dangerousness/damage of all suicide attempts was determined using the Beck Lethality Rating Scale (17). This anchored scale is used to rate the severity of medical damage (from 0=no or minimal medical consequences to 8=death) on the basis of the severity of the physical injury and the intensity of the medical interventions required. Specific anchor points were given for different methods so that lethality or medical damage could be compared across methods.

We conducted direct interviews with a subgroup of 64 patients (lifetime suicide attempts=10, current ideation about suicide=22, and no attempt/ideation=32) who had given informed consent for interviews. Patients included in this part of the study met the criteria for DSM-III-R schizophrenia or schizophreniform or schizoaffective disorder on the basis of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (18). They were interviewed within the first 5 days of admission to the hospital by using a brief, semistructured interview that focused on their history of suicidal ideation and behavior. Interrater agreement between clinical interview on admission to the hospital and the research interview was determined by using Cohen’s kappa coefficient.

Data Analysis

Two-tailed nonparametric statistical tests were used to examine the relationship between suicidal behavior and categorical variables such as sex, race, marital status, medication status, living situation, and family contact. Two-tailed parametric tests were used to evaluate the relationship between suicidal behavior and continuous variables.

RESULTS

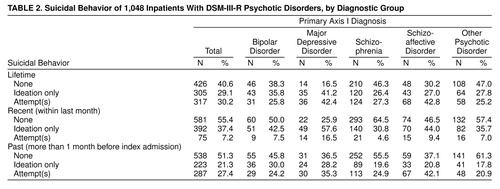

The demographics of the study group are presented by diagnostic group in Table 1. The mean age was 34.10 years (SD=9.58). The frequency of suicidal behavior by diagnostic group is presented in Table 2.

Across all subjects, patients who made a recent suicide attempt were younger (mean=29.96 years, SD=8.07) than both those who had no recent attempts or ideation (mean=35.11, SD=9.67) and those who recently thought about suicide (mean=33.41, SD=9.47) (F=11.49, df=2, 1047, p<0.001). This finding was consistent for all diagnostic groups as well. Prevalence rates for recent suicide attempts were highest within the 20–29-year-old group (12.7%, N=36 out of 283) compared with the following age groups: 6.2% (N=4 out of 65) for the 15–19-year-olds, 6.4% (N=25 out of 392) for the 30–39-year-olds, 4.1% (N=10 out of 243) for the 40–49-year-olds, and 0% for the 50–55-year-olds (χ2=22.04, df=4, p<0.0002). Sex and race failed to show any significant relationship to recent or lifetime status of suicide attempts across diagnoses.

Rates for the three categories of recent suicidal behavior differed significantly across diagnoses (χ2=56.23, df=8, p<0.0001). Patients with major depressive episodes with psychotic features (major depressive disorder) showed the highest rates of recent suicidal ideation (57.6%, N=49) and recent attempts (16.5%, N=14). The second highest rate of recent suicidal behavior was observed among the patients with schizoaffective disorder (ideation: 44.0%, N=70, and attempts: 9.4%, N=15). The lowest rates of recent suicidal ideation (23%, N=6 out of 26) and attempts (4%, N=1 out of 26) were noted among those with a diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder. Lifetime rates of suicidal behavior varied across diagnoses (χ2=46.37, df=8, p<0.0001) in a pattern consistent with the rates for recent suicidal behavior.

Ratings of the lethality of recent suicide attempts were higher for patients with schizophrenia spectrum psychoses (schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder) than for patients with affective psychoses (major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder). Patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder had similar lethality ratings for suicide attempts. Forty-four percent (N=16 out of 36) of attempts made by patients with schizophrenia spectrum psychoses resulted in physical injuries requiring medical evaluation for possible intervention (i.e., a medical lethality rating of 2 or more), compared to only 17% (N=4 out of 61) of attempts by patients with affective psychoses (χ2=4.58, df=1, p<0.05).

Five hundred sixty-four patients (54%) came into the hospital taking a psychotropic medication. Of these, 419 were taking an antipsychotic, 129 were taking an antidepressant, and 116 were taking lithium. One hundred fifty-two were taking both an antipsychotic and either an antidepressant or lithium.

No significant relationship was found between history of suicide attempts and current medication status (i.e., taking versus not taking psychotropic prescription drugs) at admission to the hospital. A majority (59%, N=44 out of 75) of the patients who had made a recent attempt reported having taken prescribed medications up to the time of admission. This was not significantly different from the rate for those not recently attempting suicide (53%, N=520 out of 973).

Individuals reporting minimal social contact (less than 5 hours per week in the last month) with a relative/significant other had a higher lifetime rate of suicide attempts than individuals with regular social contact (χ2=4.08, df=1, p<0.05). There was no association between recent social contact and recent suicide attempts.

Two hundred seventy-nine patients (26.6%) were readmitted to our hospital at least once during the 28-month study period. Among those readmitted, patients with a suicide attempt within 1 month of the index admission had more readmissions (mean=1.88, SD=1.82) over the study period than did individuals without a recent suicide attempt (mean=1.52, SD=1.18) (t=2.44, df=1045, p<0.05). A similar relationship was found for the number of readmissions among those attempting suicide in their lifetime (mean=1.72, SD=1.55) versus those who did not attempt suicide in their lifetime (mean=1.48, SD=1.10) (t=–2.84, df=1045, p<0.01). Examination by diagnosis revealed that this relationship was specific to schizophrenia readmissions (those attempting suicide in their lifetime: mean=2.52, SD=1.94, and those not attempting suicide in their lifetime: mean=1.63, SD=1.25) (t=3.10, df=452, p<0.01).

Of the 279 patients who had more than one admission to our facility over the study period, 22 (8%) were readmitted following a repeat suicide attempt, and 13 (5%) were readmitted for their first-ever attempt. Among patients with a lifetime suicide attempt at the time of index admission, a higher proportion were readmitted to the hospital after a suicide attempt (22%, N=22 out of 98) than those initially admitted without a previous suicide attempt (7%, N=13 out of 181) (χ2=13.51, df=1, p<0.01).

Agreement between the emergency room and research interviewers was good for overall classification of both recent (kappa=0.81) and past (kappa=0.89) suicidal behavior (two interviewers evaluating 64 patients). In seven of the 64 cases, there was disagreement between the emergency room admission interviewer and the research interviewer (E.D.R. or another). In six of these cases, the emergency room staff rated suicidal behavior as less severe than did the research interviewer (E.D.R. or another) (e.g., ideation rather than attempt or no ideation rather than ideation).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first report on lifetime rates of suicidal behavior in a large, broadly defined clinical study group of individuals with psychotic disorders. Before this, no study had been able to determine whether the risk for suicidal behavior was elevated among psychotic patients in general. The results of this study provide empirical evidence for a high frequency of suicidal behavior among patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital with axis I psychotic disorders. Recent suicidal ideation was reported by 37.4% (N=392) of the entire group, and 7.2% (N=75) reported a suicide attempt within 1 month before hospital admission. Almost one-third (30.2%, N=317) of all patients had made a suicide attempt at some point in their lives.

Results from the present study indicate that risk factors associated with suicidal behavior in patients with psychosis are different from those in the general population. Data from the five-site NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area study identified the following risk factors for attempted suicide in the general community: a lifetime diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder and being female, separated or divorced, Caucasian, and of low socioeconomic status (19). In our group, the observation that women with psychosis did not have a higher risk for suicidal behavior than men with psychosis contrasts markedly with the demographics of nonlethal suicide attempts in the general population group from the Epidemiological Catchment Area study. In addition, our data did not show that Caucasians had a higher relative risk for suicide attempts than that of African Americans. Our findings are consistent with the results of a study of those who attempted suicide in Edinburgh between 1968 and 1981 (20), which also reported the absence of a higher relative risk for women and Caucasians in a group of patients with schizophrenia.

Although being separated or divorced did not confer a higher risk for suicide attempts in our group, as it does in the general population, a lack of regular contact with a significant other was associated with the status of suicide attempt during a lifetime. This suggests that the assessment of the quantity of contact may be more important than marital status alone for evaluating the risk of suicide in patients with psychosis, consistent with the classic work of Durkheim (21), who suggested that the risk for suicide is related to the severity of anomie. Because of the significant short- and long-term social difficulties (e.g., social withdrawal and social skills deficits) characteristic of many individuals with psychotic disorders, the lack of regular social contact may be an important factor associated with long-term risk for suicidal behavior in this population. This raises the possibility that treatments designed to enhance social networks might have value in reducing the risk for suicidal behavior among patients with psychosis.

Somewhat unexpected was the finding that the lifetime frequency of suicide attempts was high (between 23% and 42%) for all categories of psychotic disorders—with the exception of schizophreniform disorder. Although the existing literature suggests that the risk of suicide is highest during the first 10 years of schizophrenia (22), the lower attempt rate (within the last month) in the patients with schizophreniform disorder suggests that the risk for suicide may be lower near the onset of schizophrenia spectrum disorders and then increase over the early years of the disorders. This finding is consistent with our data showing a lower risk for suicide attempts early in the course of schizophrenia spectrum illnesses (23).

Although suicide attempts are considerably more common than completed suicides (20) and are associated with considerable social and physical morbidity, most empirical reports on the correlates of suicidal behavior have focused on suicide completions. In the general population, those who attempt and those who complete suicide tend to differ in terms of sex, race, and age, with those attempting suicide tending to be young white women and those completing suicide tending to be older white men (24).

Consistent with age-related patterns of suicide completion (25) and attempts (14) in schizophrenia, we found that patients with psychotic disorders are at highest risk for all suicidal behavior when they are young adults—regardless of their particular type of psychotic disorder. While the risk for suicide completion among patients with schizophrenia between the ages of 18 and 55 years appears to decrease with age, in the general population, the risk for suicide completion tends to remain steady within age ranges (24).

The relationship of sex to suicidal behavior in schizophrenia is not as consistent. In the general population, most studies have shown that men tend to complete suicide, whereas women tend to attempt suicide. In patients with psychotic disorders, the sexes appear to be equally represented among those who attempt and those who complete suicide (16, 20, 26).

Our finding that patients with a previous suicide attempt had more hospital readmissions is consistent with studies examining both those who completed (27) and those who attempted suicide (26, 28). This suggests that patients with schizophrenia who have attempted suicide are more likely to be rehospitalized. It remains to be determined whether this effect is because of a higher risk for relapse, readmission for suicide risk rather than reemergence of psychotic symptoms, or a lower threshold for hospitalization for individuals seen as being at risk for suicide. In any case, this observation indicates a need for the development of special long-term treatment strategies for patients with schizophrenia who also have a history of suicide attempts.

The presence of a psychiatric disorder is the most robust risk factor for attempted suicide in all age groups (19), with patients with comorbid diagnoses (29) and more severe forms of mental illness (28) at highest risk. In schizophrenia, the risk for suicidal behavior, both attempts and completions, is significantly elevated when there are concomitant depressive symptoms (16, 28, 30, 31). It is important that risk may also be higher in affective disorders when psychotic symptoms are present (11, 32). In the present study, while the rates of suicidal behavior were greatest among patients with psychosis and a concomitant depressive syndrome, the medical severity of recent suicide attempts was highest among patients with schizophrenia spectrum psychoses (schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder).

Although the effectiveness of antidepressants in alleviating depressive symptoms in general is well documented, their value in managing suicidal ideation and behavior in patients with psychotic disorders is relatively unclear. Our data do not permit a comparison of more complex medication variables, such as adequacy of dose and compliance, nor do they indicate any strong conclusions about antidepressant efficacy, but they do suggest that the efficacy of psychotropic medication as a treatment for patients with psychosis who are at risk for suicidal behavior deserves more in-depth inquiry.

Results of the present study indicate that overall reliability between clinical and research interviewers was high with regard to the classification of both recent and past suicidal ideation and behavior. These data suggest that the reliability of the assessment of suicidality in patients with psychosis can be performed adequately. However, where disparities occurred, most represented underreporting or underrecognition of suicidal behavior in the emergency room. This may result from the immediate task of evaluating patients seeking help for acute psychosis, which may focus evaluations on immediate clinical problems of hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorder without adequate attention to the assessment of suicide risk.

The results of the present study should be interpreted in light of the limitations of the study design. First, this study was limited in scope by the relatively narrow range of the social, demographic, and clinical correlates or risk factor variables that could be obtained from medical records. We chose variables that were both objective and consistently available for our large group. Although we were able to report on some of the most widely studied variables (e.g., age, sex, race), we could not adequately evaluate more complex variables such as age at onset of illness, compliance with and adequacy of antipsychotic and antidepressant medication, and extent of substance abuse/dependence. Second, we relied on a clinical diagnosis at admission in this large, consecutively admitted cohort, and thus replication of our observation is needed with standardized, structured diagnostic interview procedures. Finally, the data on hospital readmissions were limited to patients who returned to the emergency service at our facility and do not include information about the suicidal behavior of patients readmitted to other inpatient facilities during the study period. To more adequately evaluate the risk for emergency treatment and rehospitalization among patients with acute suicidal psychosis, prospective record linkage studies are needed.

In this study, a large consecutively admitted series of psychotic psychiatric inpatients was studied to identify demographic and clinical attributes associated with lifetime suicidal behavior among individuals with axis I psychotic disorders. Patient subgroups in whom suicide attempts were most prevalent were younger, more socially isolated, and more likely to have a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder or major depression with psychotic features. Further study is needed to explore the factors mediating the above findings, to understand the relative contributions that psychosis and depression each have to the continuum of suicidal behavior (i.e., from ideation to suicide completion), and to develop preventive interventions to reduce the risk of suicidal behavior.

Received Sept. 3, 1998; revision received March 15, 1999; accepted March 24, 1999. From the Family and Psychosocial Studies Program, Department of Psychiatry, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Address reprint requests to Dr. Radomsky, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Rm. 985, 3811 O’Hara St., Pittsburgh, PA 15213; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-48492 (Dr. Haas), MH-46745 (Dr. Mann), and MH-42969 (Dr. Sweeney). The authors thank Larry Glanz, Ph.D., and Richelle Henderson, M.S.W., for help with clinical evaluations and Eric Yablonsky for assistance with data management.

|

|

1. Caldwell CB, Gottesman II: Schizophrenics kill themselves too: a review of risk factors for suicide. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16:571–589Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Miles CP: Conditions predisposing to suicide: a review. J Nerv Ment Dis 1977; 164:231–246Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Roy A: Suicide in schizophrenia, in Suicide. Edited by Roy A. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1986, pp 97–109Google Scholar

4. Drake RE, Gates C, Whitaker A, Cotton PG: Suicide among schizophrenics: a review. Compr Psychiatry 1985; 26:90–100Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Johns CA, Stanley M, Stanley B: Suicide in schizophrenia, in Psychobiology of Suicidal Behavior. Edited by Mann JJ, Stanley M. New York, New York Academy of Sciences, 1986, pp 294–300Google Scholar

6. Caldwell CB, Gottesman II: Schizophrenia—a high-risk factor for suicide: clues to risk reduction. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1992; 22:479–493Medline, Google Scholar

7. Haas GL: Suicidal behavior in schizophrenia, in Review of Suicidology, 1997. Edited by Maris RW, Silverman NM, Canetto SS. New York, Guilford Press, 1997, pp. 202–236Google Scholar

8. Roy A: Depression, attempted suicide, and suicide in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1986; 9:193–206Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Weiden P, Roy A: General versus specific risk factors for suicide in schizophrenia, in Suicide and Clinical Practice. Edited by Jacobs D. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1992, pp 75–100Google Scholar

10. Taiminen TJ, Kujari H: Antipsychotic medication and suicide risk among schizophrenic and paranoid inpatients: a controlled retrospective study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 90:247–251Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Axelsson R, Lagerkvist-Briggs M: Factors predicting suicide in psychotic patients. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1992; 241:259–266Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Westermeyer JF, Harrow M, Marengo JT: Risk for suicide in schizophrenia and other psychotic and nonpsychotic disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis 1991; 179:259–266Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Roose SP, Glassman AH, Walsh BT, Woodring S, Vital-Herne J: Depression, delusions, and suicide. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:1159–1162Google Scholar

14. Black DW, Winokur G, Nasrallah A: Effect of psychosis on suicide risk in 1,593 patients with unipolar and bipolar affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:849–852Link, Google Scholar

15. Fawcett J, Scheftner WA, Fogg L, Clark DC, Young MA, Hedeker D, Gibbons R: Time-related predictors of suicide in major affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1189–1194Google Scholar

16. Dassori AM, Mezzich JE, Keshavan M: Suicidal indicators in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1990; 81:409–413Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Beck AT, Beck R, Kovacs M: Classification of suicidal behaviors, I: quantifying intent and medical lethality. Am J Psychiatry 1975; 132:285–287Link, Google Scholar

18. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: Instruction Manual for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1988Google Scholar

19. Moscicki EK, O’Carroll PW, Rae DS, Roy AG, Locke BZ, Regier DA: Suicidal ideation and attempts: the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, in Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Youth Suicide, vol IV: Strategies for the Prevention of Youth Suicide. Edited by Rosenberg ML, Baer K. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1988, pp 115–128Google Scholar

20. Wilkinson G, Bacon NA: A clinical and epidemiological survey of parasuicide and suicide in Edinburgh schizophrenics. Psychol Med 1984; 14:899–912Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Durkheim E: Suicide: A Study in Sociology. Translated by Spaulding JA, Simpson G. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1952Google Scholar

22. Virkkunen M: Suicides in schizophrenia and paranoid psychoses. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1974; 250:1–305Medline, Google Scholar

23. Radomsky ED, Haas GL, Keshavan MS, Sweeney JA: Suicidal behavior before the first hospitalization in psychotic disorders (abstract). Schizophr Res 1997; 24:256Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Moscicki EK: Epidemiology of suicidal behavior. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1995; 25:22–35Medline, Google Scholar

25. Roy A: Suicide in chronic schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1982; 141:171–177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Landmark J, Cernovsky ZZ, Merskey H: Correlates of suicide attempts and ideation in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 151:18–20Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Rossau CD, Mortensen PB: Risk factors for suicide in patients with schizophrenia: nested case-control study. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 171:355–359Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Addington DE, Addington JM: Attempted suicide and depression in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 85:288–291Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Henriksson MM, Aro HM, Marttunen MJ, Heikkinen ME, Isometsä ET, Kuoppasalmi KI, Lonnqvist JK: Mental disorders and comorbidity in suicide. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:935–940Link, Google Scholar

30. Roy A: Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:1089–1095Google Scholar

31. Prasad AJ: Attempted suicide in hospitalised schizophrenics. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1986; 74:41–42Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Roy A, Mazonson A, Pickar D: Attempted suicide in chronic schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1984; 144:303–306Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar