Age of Methylphenidate Treatment Initiation in Children With ADHD and Later Substance Abuse: Prospective Follow-Up Into Adulthood

Abstract

Objective: Animal studies have shown that age at stimulant exposure is positively related to later drug sensitivity. The purpose of this study was to examine whether age at initiation of stimulant treatment in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is related to the subsequent development of substance use disorders. Method: The authors conducted a prospective longitudinal study of 176 methylphenidate-treated Caucasian male children (ages 6 to 12) with ADHD but without conduct disorder. The participants were followed up at late adolescence (mean age=18.4 years; retention rate=94%) and adulthood (mean age=25.3; retention rate=85%). One hundred seventy-eight comparison subjects also were included. All subjects were diagnosed by blinded clinicians. The Cox proportional hazards model included the following childhood predictor variables: age at initiation of methylphenidate treatment, total cumulative dose of methylphenidate, treatment duration, IQ, severity of hyperactivity, socioeconomic status, and lifetime parental psychopathology. Separate models tested for the following four lifetime outcomes: any substance use disorder, alcohol use disorder, non-alcohol substance use disorder, and stimulant use disorder. Other outcomes included antisocial personality, mood, and anxiety disorders. Results: There was a significant positive relationship between age at treatment initiation and non-alcohol substance use disorder. None of the predictor variables accounted for this association. Post hoc analyses showed that the development of antisocial personality disorder explained the relationship between age at first methylphenidate treatment and later substance use disorder. Even when controlling for substance use disorder, age at stimulant treatment initiation was significantly and positively related to the later development of antisocial personality disorder. Age at first methylphenidate treatment was unrelated to mood and anxiety disorders. Conclusions: Early age at initiation of methylphenidate treatment in children with ADHD does not increase the risk for negative outcomes and may have beneficial long-term effects.

Numerous studies have shown that childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is significantly associated with adolescent and adult substance use disorders (1 – 8) . Additionally, stimulants are considered first-line treatments for children with ADHD (9 , 10) . Animal studies have raised concern regarding stimulant treatment because of findings of sensitization to the effects of drugs. The sensitization hypothesis, a neuroadaptional model, maintains that exposure to stimulants results in dopamine system alterations, which in turn increase sensitivity to the reinforcing effects of the previously experienced substance. Behavioral sensitization has been demonstrated in numerous mammalian species, including nonhuman primates, and has been found to be long lasting (11 , 12) . Consistent with this model, some studies have suggested that there may be a causal link between stimulant treatment in childhood and later substance use disorder (13 , 14) . The potential role of stimulants in the pathogenesis of substance use disorder is a major public health concern, since stimulant use is widespread and these medications are increasingly prescribed to young children (15) . Of relevance to this controversy, some animal studies have reported developmental effects on stimulant sensitization. Specifically, later preference for cocaine in rats is decreased by early relative to later methylphenidate administration (16 , 17) , suggesting that age at exposure may modulate long-term drug effects on the brain, at least in rats.

More than one dozen studies have examined the association between stimulant treatment of ADHD and substance use disorder (18 – 20) and, with one exception (21) , have not found a significant positive relationship. In non-ADHD children treated with methylphenidate or placebo, we also did not find a relationship between exposure to methylphenidate and substance use disorder in adulthood (22) . To our knowledge, no study has examined the association between age at first exposure to stimulants and later substance use disorder. The objective of the present study was to examine possible relationships between age at initiation of methylphenidate treatment and the later development of substance use disorder. The data presented are on a clinic sample of male children with ADHD who were prospectively followed and systematically assessed in late adolescence (3 , 4) and adulthood (5 , 6) by blinded clinicians. Stimulant treatment began as early as age 6 for some children and as late as age 12 for others.

Method

Participants

Participants were 6- to 12-year-old Caucasian boys of middle socioeconomic status who were referred to a no-cost child psychiatric research clinic in New York between 1970 and 1977 (23 , 24) . The criteria were 1) referrals by schools because of behavior problems, 2) elevated ratings on standard scales of hyperactivity by teachers and parents, 3) behavior problems in settings other than school, 4) a diagnosis of DSM-II hyperkinetic reaction by a child psychiatrist based on interviews with participants and their mothers and school information, 5) no previous significant treatment with stimulants (defined as more than 10 mg/day of methylphenidate for more than 1 month), 6) an IQ score ≥85 (25 , 26) , 7) no evidence of psychosis or neurological disorder, 8) English-speaking parents, and 9) a home telephone. The exclusion of previously treated children did not incur any appreciable loss of subjects, since stimulants were not used in the community during the 1970s.

Children were excluded if the referral involved aggressive or other serious antisocial behaviors or if the psychiatric assessment with parent and child revealed a pattern of antisocial activities. These exclusion criteria were implemented to rule out children with conduct disorders because of the controversy concerning the diagnostic distinction between hyperactivity and conduct disorder. To determine whether conduct problems were successfully excluded, we examined the ratings on the following two measures: the Conners Teacher Rating Scale (27) and the Conners Parent Rating Scale (28) (range: 0 [not at all] to 3 [very much]). The overall mean of combined parent and teacher ratings on items corresponding with DSM-IV conduct disorder behaviors (bullying, lying, stealing, truancy, etc.) was very low (mean=0.7 [SD=0.4]), which shows that the frequency of conduct problems was extremely scarce.

Probands would have met criteria for DSM-IV ADHD combined type, since 1) cross situationality of hyperactivity was required; 2) all subjects were clinically impaired by ADHD; 3) relatively severe hyperactivity was required; 4) mean ratings on the Conners Teacher Rating Scale items of restless/overactive, inattentive/distractible, and excitable/impulsive (rated 0–3) were 2.8, 2.6, and 2.4, respectively; and 5) classroom observation ratings determined by blinded observers showed highly significant differences between index and “normal” children on items related to hyperactivity (“out of chair”), inattention (“off task”), and impulsivity (“interference”) (29) .

Of 207 ADHD probands in the entire childhood cohort, 182 were treated with methylphenidate, administered b.i.d. The remaining 25 either refused treatment or were noncompliant. Among those who were treated, six (3%) refused participation in the follow-ups. Thus, the present study included the 176 probands (97%) who were treated with methylphenidate in childhood and who participated in the follow-up assessments.

A non-ADHD Caucasian male comparison group (N=178), matched for age, social class, and geographic residence, was recruited at the late-adolescent follow-up (3 , 4) .

Prospective Follow-Ups

Participants were evaluated in late adolescence (mean age=18.4 [SD=1.3] years; 94% retention) and adulthood (mean age=25.3 [SD=1.3] years; 85% retention). At both follow-up assessments, ADHD probands and non-ADHD comparison subjects were systematically interviewed by clinicians who were blind to childhood status (3 – 6) . For both follow-ups, written informed consent was obtained after the study purpose and procedures were fully explained.

At the late-adolescent follow-up, subjects were administered a modification of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (30) , the Teenager or Young Adult Schedule, which is a systematic clinical interview that includes DSM-III attention deficit, conduct, substance use, mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders. Parents were administered the Parent Interview (3) . Diagnoses were considered present if they were determined on the basis of either the informant assessment or self-assessment. Interrater reliability was excellent for both self- and informant assessments (attention deficit disorder: kappa=0.85 and 0.91; conduct disorder: kappa=0.93 and 0.75; substance use disorder: kappa=0.81 and 0.88; any DSM-III disorder: kappa=0.79 and 0.83, respectively) (4) .

At the adult follow-up, subjects were administered the Schedule for the Assessment of Conduct, Hyperactivity, Anxiety, Mood, and Psychoactive Substances (31) , which includes lifetime DSM-III-R antisocial personality disorder, ADHD, substance use disorder, and mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders. Interrater reliability was good to excellent for all major disorders (antisocial personality disorder: kappa=0.69; ADHD: kappa=0.70; substance use disorder: kappa=0.80; mood disorder: kappa=1.00; any DSM-III-R disorder: kappa=0.67) (5) .

Parent Diagnostic Assessments

At the first follow-up, parents were administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (30) by independent blinded clinicians. Attempts were made to interview both parents directly. However, when one parent was not accessible (e.g., deceased, estranged), the other parent was administered the Spouse Informant Schedule, a semistructured interview derived from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for the present study. The Spouse Informant Schedule includes sections on DSM-III alcohol and nonalcohol substance use disorders, antisocial personality disorder, and attention deficit disorder. Diagnostic interviews were obtained for the parents of 146 (83%) of the 176 participants. Of these, nearly all mothers (97%) were directly interviewed, but informant interviews were obtained for only two-thirds (65%) of the fathers.

Data Analyses

Model employed

The Cox proportional hazards model (32) was used to assess the relationship between age at methylphenidate treatment initiation in childhood and later development of substance use disorder. Substance use disorder was considered present if it was diagnosed at either late-adolescent or adult follow-up (i.e., lifetime substance use disorder).

Four survival analyses were conducted with the following nonmutually exclusive outcome measures: any substance use disorder, alcohol use disorder, non-alcohol substance use disorder (cannabis, opiates, cocaine, etc.), and stimulant use disorder (cocaine, amphetamines, etc.). The rationale for including these outcome variables was that 1) it was of interest to determine whether the relationship between age at initiation and later stimulant use disorder differed from other substance use disorder categories, since subjects were treated with stimulants in childhood, and 2) separate categories for alcohol and non-alcohol substance use disorders were included, since our late-adolescent and adult follow-ups showed that probands were at significantly increased risk for non-alcohol substance use disorder but not alcohol use disorder relative to comparison subjects (3 – 6) . Age at the most recent interview was used as the time of censoring for noncase subjects (i.e., subjects with no substance use disorder diagnosis). Similar post hoc analyses examined the relationship between age at first methylphenidate treatment and later antisocial personality, anxiety, and mood disorders.

Alternative explanations

Since age at first exposure to methylphenidate treatment was not a random characteristic, we considered whether other factors might have accounted for the development of substance use disorder. The following factors were included in the analyses:

1. Characteristics of methylphenidate treatment . Treatment exposure (dosage and duration) might have varied as a function of children’s ages. To address this possibility, the effects of the total cumulative dose (mg) of methylphenidate treatment and duration (months) of treatment were assessed.

2. Characteristics of participants . Childhood IQ was entered, since a significant relationship between IQ and substance use disorder has been reported (33) . In addition, the severity of childhood hyperactivity, as measured by the Hyperactivity Factor of the Conners Teacher Rating Scale (28) , was included.

3. Other variables possibly related to substance use disorder . In addition to treatment and subject characteristics, socioeconomic status and parent psychopathology have been related to substance use disorder in offspring (34 – 36) . The Hollingshead and Redlich two-factor index (37) was used to assess socioeconomic status. We also examined the effects of lifetime DSM-III diagnoses of parents.

Building and testing the model

In summary, the following nine predictor variables were initially included: 1) child’s age (years) at initiation of methylphenidate treatment; 2) total cumulative dosage (mg); 3) total duration (months) of treatment; 4) childhood full-scale IQ; 5) severity of childhood hyperactivity (28) ; 6) socioeconomic status in childhood (37) ; and lifetime mental disorder in the 7) mother, 8) father, or 9) either parent (entered separately and rated dichotomously). As described by Hosmer and Lemeshow (38) , the following data analytic strategy was employed: Step 1, univariate analyses were conducted for all continuous (using proportional hazards analyses) and dichotomous (using Kaplan-Meier analyses) predictor variables with each of the four outcome variables (any substance, alcohol, non-alcohol substance, and stimulant use disorders); Step 2, variables showing a p value less than 0.20 (two-tailed) in the univariate analyses were entered together into the proportional hazards analyses; and Step 3, variables showing a p value greater than 0.05 (two-tailed) were discarded, and proportional hazards analyses were rerun with the remaining variables and their interactions. Proportional hazards assumptions also were tested in the final model.

Results

Predictor Variables

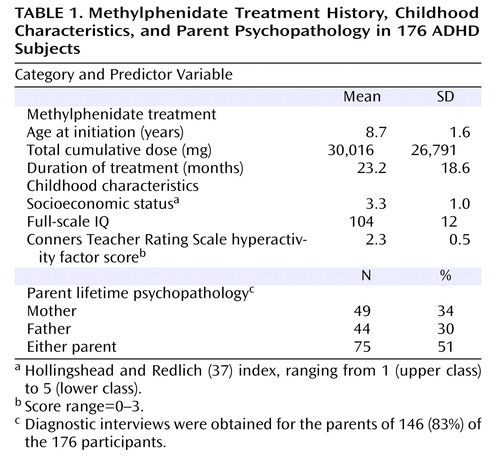

The distribution of the 176 participants by age at initiation of methylphenidate treatment was as follows: 6 years, 25 subjects (14%); 7 years, 49 subjects (28%); 8 years, 29 subjects (16%); 9 years, 28 subjects (16%); 10 years, 23 subjects (13%); 11 years, 19 subjects (11%); and 12 years, 3 subjects (2%). The daily dosage of methylphenidate was 41.7 (SD=12.4) mg. The means for the nine predictor variables are shown in Table 1 . Participants were middle class, of average intelligence, and had relatively severe ratings of hyperactivity (mean ratings=2.3 [out of possible 3.0]). One-third of the mothers, one-third of the fathers, and one-half of parents in the either parent predictor variable had a lifetime mental disorder.

Outcome Variables

Among the 176 participants treated, 80 (45%) fulfilled criteria for substance use disorder at some time in their lives. Of these, 49 (28%) had alcohol use disorder, and 65 (37%) met criteria for non-alcohol substance use disorder. Forty-three (24%) of those individuals who met criteria for non-alcohol substance use disorder also fulfilled criteria for stimulant use disorder.

Building and Testing the Model

First, univariate analyses were conducted for the nine predictor variables with each of the four outcome variables.

Any substance use disorder

The following two predictor variables had p values less than 0.20: age at initiation of treatment (Wald χ 2 =3.47, p<0.06) and socioeconomic status (Wald χ 2 =2.47, p<0.12).

Alcohol use disorder

Only one predictor variable had a p value less than 0.20: treatment duration (Wald χ 2 =1.75, p<0.19).

Non-alcohol substance use disorder

The following two predictor variables had p values less than 0.20: age at initiation of treatment (Wald χ 2 =4.92, p<0.03) and socioeconomic status (Wald χ 2 =2.86, p<0.09).

Stimulant use disorder

Only one predictor variable had a p value less than 0.20: age at initiation of treatment (Wald χ 2 =3.33, p<0.07).

Since only one predictor variable was associated with alcohol use and stimulant use disorders (p>0.05), no further analyses were conducted for these two outcomes. For any substance use and non-alcohol substance use disorder, the two predictor variables that showed promise, age at initiation and socioeconomic status, were entered together and rerun in the proportional hazards analyses. The only predictor variable that remained significant (p<0.05) was age at initiation of stimulant treatment, only for the non-alcohol substance use disorder outcome (Wald χ 2 =4.24, p<0.04). Participants who developed non-alcohol substance use disorder (N=65) were treated at a significantly later age relative to those who never developed non-alcohol substance use disorder (N=111) (mean=9.10 [SD=1.74] years versus 8.52 [SD=1.55] years, t=2.31, df=174, p=0.02).

We also compared the rates of non-alcohol substance use disorder in probands with rates of the disorder in the 178 non-ADHD comparison subjects. ADHD probands were classified as early- (methylphenidate treatment began at age 6 or 7) and late-treated (methylphenidate treatment began at ages 8 to 12). The division was made at age 8, since this was the sample mean and median. Lifetime rates of substance use disorder were significantly greater among late-treated probands relative to early-treated probands (44% versus 27%; Wald χ 2 =5.38, p<0.02) and non-ADHD comparison subjects (44% versus 29%; Wald χ 2 =6.36, p<0.02), with no difference between the two latter groups (27% versus 29%; Wald χ 2 =0.12, p>0.10).

We also considered that the persistence of ADHD might have accounted for the relationship between age at stimulant initiation and the development of substance use disorder. To examine this possibility, we conducted a survival analysis with age at initiation and age at ADHD offset as predictor variables and non-alcohol substance use disorder as the outcome variable. Results showed that age at stimulant initiation significantly predicted substance use disorder outcome when controlling for the offset of ADHD (Wald χ 2 =3.78, p=0.05), but age at offset of ADHD did not predict the development of substance use disorder when controlling for age at stimulant initiation (Wald χ 2 =2.51, p>0.10). In other words, age of desistance of ADHD was not relevant; only the age at which stimulant treatment was started predicted substance use disorder.

Finally, we examined the specificity of the relationship—i.e., Does age at initiation of methylphenidate treatment predict only substance use disorder or also the development of other disorders? Separate survival analyses were conducted for the following lifetime diagnoses: antisocial personality, mood, and anxiety disorders. Results showed that only antisocial personality disorder was significantly and positively associated with age at stimulant initiation (Wald χ 2 =14.87, p<0.001). Mood (Wald χ 2 =1.35, p>0.10) and anxiety disorders (Wald χ 2 =0.40, p>0.10) were not associated with age at stimulant initiation.

Post Hoc Analyses of Antisocial Personality Disorder and Substance Use Disorder

It is not surprising that age at initiation was significantly associated with both substance use disorder and antisocial personality disorder, since follow-ups of our sample consistently showed substantial comorbidity between substance use disorder and antisocial personality disorder (3 – 6) . This finding raised the possibility that antisocial personality disorder accounted for the substance use disorder treatment initiation relationship. Therefore, the following two additional survival analyses were conducted: 1) one with antisocial personality disorder as the outcome and non-alcohol substance use disorder as the covariate and 2) the other with substance use disorder as the outcome and antisocial personality disorder as the covariate. The first analysis showed that age at first methylphenidate treatment remained significantly associated with antisocial personality disorder when substance use disorder was covaried (Wald χ 2 =7.67, p<0.01). However, when we controlled for antisocial personality disorder, the relationship between treatment initiation and substance use disorder was no longer present (Wald χ 2 =0.09, p=0.76).

This finding raised the possibility that children who were referred relatively later for treatment had higher levels of conduct problems relative to children who were referred earlier. If this was indeed the case, conduct problems in childhood could have accounted for higher subsequent rates of both antisocial personality disorder and substance use disorder, and age at methylphenidate initiation would have been irrelevant to later substance use disorder. Such a possibility seems viable, since even in our sample with very low conduct problems, we found that the severity of such problems predicted later antisocial personality disorder (39) . However, there was no relationship, not even a tendency, between age at first methylphenidate treatment and the severity of conduct problems (measured by teacher ratings) (r=0.05, df=176, p=0.49).

A second possibility was that parents with antisocial personality disorder or substance use disorder were relatively less diligent about bringing their child in for treatment, perhaps accounting for the apparent relationship between age at first stimulant treatment and the later development of substance use and antisocial personality disorders in the child. This possibility was examined in three ways. First, age at first methylphenidate treatment was compared for offspring of parents with and without these disorders. The mean of stimulant initiation was 8.3 (SD=1.6) years for offspring of parents with antisocial personality disorder versus 8.7 (SD=1.6) years for offspring of parents without antisocial personality disorder (t=0.61, p=0.54). The mean of stimulant initiation was 8.5 (SD=1.0) years for offspring of parents with substance use disorder versus 8.8 (SD=1.6) years for offspring of parents without substance use disorder (t=0.75, p=0.45). The mean of stimulant initiation was 8.5 (SD=1.7) years for offspring of parents with antisocial personality or substance use disorder versus 8.8 (SD=1.6) years for offspring of parents without antisocial personality or substance use disorder (t=0.75, p=0.45). Point biserial correlations for age (years) at first methylphenidate treatment with the presence or absence of mental disorder were as follows: 1) parent antisocial personality disorder: r=–0.05, df=176, p=0.54; 2) parent substance use disorder: r=–0.06, df=176, p=0.45; and 3) parent antisocial personality or substance use disorder: r=–0.06, df=176, p=0.45. Last, we compared early- and late-treated subjects on the rates of antisocial personality and substance use disorders in parents (antisocial personality disorder: 3% [early treated] versus 5% [late treated], p=0.37; substance use disorder: 25% [early treated] versus 18% [late treated], p=0.69; antisocial personality disorder or substance use disorder: 25% [early treated] versus 18% [late treated], p=0.69). In summary, we found no relationship between antisocial personality or substance use disorder in parents and age at initiation of stimulant treatment.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective follow-up study to examine the relationship between age of initiation of methylphenidate treatment for ADHD and the subsequent development of substance use disorder, as well as other disorders. The risk of developing substance use disorder was significantly associated with age at methylphenidate treatment; specifically, the later the treatment, the greater the chances of developing substance use disorder. The principal value of this finding is that it challenges the position that early exposure to stimulants presents particular risk to children with ADHD, at least with regard to substance use and antisocial personality disorders.

Unexpectedly, the development of antisocial personality disorder accounted for the association between age at first treatment with methylphenidate and substance abuse. This association was not the result of age-related differences in early conduct problems. Although these findings are consistent with animal data suggesting that later preference for cocaine in rats is relatively decreased by exposure to methylphenidate in early rather than late development (16 , 17) , the relevance of animal neurodevelopmental models of stimulant exposure is not straightforward. The relationship between age at first stimulant exposure and later substance use disorder must account for the observation that the relationship is mediated by the development of antisocial personality disorder.

It is unclear why age at initiation of stimulant treatment and the later development of substance use and antisocial personality disorders appear to be related. Castellanos et al. (40) reported that unmedicated children with ADHD had smaller brain white matter volume relative to medicated children with ADHD and non-ADHD comparison subjects. Early stimulant treatment might increase brain functional reserve by increasing (or normalizing) brain white matter volume during a developmental period of greatest plasticity, and greater brain functional reserve may be associated with decreased risk of substance use disorder. We are presently conducting an adult follow-up study on the current sample, now age 40, in which magnetic resonance imaging scans will examine whether there are structural differences in early- and late-treated subjects.

The major limitation of the present study is that it is an experiment of nature that relied on a referred clinical sample. The age at referral was not experimentally controlled, and thus unidentified, nonrandom factors related to treatment initiation, other than those assessed, may have contributed to the relationship between age at first treatment and substance use and antisocial personality disorders. For example, parental family factors may have mediated this association, which could have resulted in a failure to attend to the needs of the child that led parents to delay treatment for their children. Parent psychopathology, in general, and parent antisocial personality and substance use disorders, in particular, do not explain this relationship, but other features related to child rearing may be relevant. Therefore, replication is essential. Other limitations include the ethnic homogeneity of our sample, exclusion of female children, and the minimum age of 6, thus restricting generalizability of results to clinic-referred 6- to 12-year-old Caucasian males. Furthermore, we do not know whether our findings apply to early stimulant exposure or to early referral for treatment, independent of methylphenidate administration. It could be that timing of interventions, regardless of their nature, affect long-term outcome. Thus, the duration of untreated ADHD in childhood, rather than stimulant treatment per se , might be the important variable. In other words, we cannot differentiate presumed effects of stimulant medication from effects of age at referral, independent of stimulant exposure.

The use of stimulants in young children has generated considerable controversy. At the least, the findings of the present study do not indicate that treatment relatively early in childhood increases risk for negative outcomes.

1. Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Mick E, Spencer T, Wilens TE, Silva JM, Snyder LE, Faraone SV: Young adult outcome of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a controlled 10-year follow-up study. Psychol Med 2006; 36:167–179Google Scholar

2. Biederman J, Wilens TE, Mick E, Faraone SV, Spencer T: Does attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder impact the developmental course of drug and alcohol abuse and dependence? Biol Psychiatry 1998; 44:269–273Google Scholar

3. Gittelman R, Mannuzza S, Shenker R, Bonagura N: Hyperactive boys almost grown up, I: psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42:937–947Google Scholar

4. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bonagura N, Malloy P, Giampino TL, Addalli KA: Hyperactive boys almost grown up, V: replication of psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:77–83Google Scholar

5. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M: Adult outcome of hyperactive boys: educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:565–576Google Scholar

6. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M: Adult psychiatric status of hyperactive boys grown up. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:493–498Google Scholar

7. Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Wilens T, Chu MP: Associations between ADHD and psychoactive substance use disorders: findings from a longitudinal study of high-risk siblings of ADHD children. Am J Addict 1997; 6:318–329Google Scholar

8. Wilson JJ, Levin FR: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and early-onset substance use disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2005; 15:751–763Google Scholar

9. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Practice parameter for the use of stimulant medications in the treatment of children, adolescents, and adults. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:26S–49SGoogle Scholar

10. American Academy of Pediatrics: Clinical practice guideline: treatment of the school-aged child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 2001; 108:1033–1044Google Scholar

11. Robinson TE, Becker JB: Enduring changes in brain and behavior produced by chronic amphetamine administration. Brain Res Rev 1986; 11:157–198Google Scholar

12. Schenk S, Davidson ES: Stimulant preexposure sensitizes rats and humans to the rewarding effects of cocaine. NIDA Res Monogr 1998; 169:56–82Google Scholar

13. Kollins SH, MacDonald EK, Cush CR: Assessing the abuse potential of methylphenidate in nonhuman and human subjects: a review. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2001; 68:611–627Google Scholar

14. Vitiello B: Long-term effects of stimulant medications on the brain: possible relevance to the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2001; 11:25–34Google Scholar

15. Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, Gardner JF, Boles M, Lynch F: Trends in the prescribing of psychotropic medications to preschoolers. JAMA 2000; 283:1025–1030Google Scholar

16. Andersen SL, Arvanitogiannis A, Pliakas AM, LeBlanc C, Carlezon WA Jr: Altered responsiveness to cocaine in rats exposed to methylphenidate during development. Nat Neurosci 2001; 5:13–14Google Scholar

17. Brandon CL, Marinelli M, Baker LK, White FJ: Enhanced reactivity and vulnerability to cocaine following methylphenidate treatment in adolescent rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 2001; 25:651–661Google Scholar

18. Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K: Does stimulant treatment of ADHD contribute to substance use and abuse? Pediatrics 2003; 111:97–109Google Scholar

19. Loney J, Kramer JR, Salisbury H: Medicated versus unmedicated ADHD children: adult involvement with legal and illegal drugs, in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: State of the Science Best Practices. Edited by Jensen PS, Cooper JR. Kingston, NJ, Civic Research Institute, 2002, pp 1–16Google Scholar

20. Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, Spencer T, Faraone SV: Pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder reduces risk for substance use disorder. Pediatrics 1999; 104:E201–E205Google Scholar

21. Lambert NM, Hartsough CS: Prospective study of tobacco smoking and substance dependence among samples of ADHD and non-ADHD participants. J Learn Disabil 1998; 31:533–544Google Scholar

22. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Moulton III JL: Does stimulant treatment place children at risk for adult substance abuse? A controlled, prospective follow-up study. J Child Adol Psychopharm 2003; 13:273–282Google Scholar

23. Gittelman R, Abikoff H, Pollack E, Klein DF, Katz S, Mattes J: A controlled trial of behavior modification and methylphenidate in hyperactive children, in Hyperactive Children. Edited by Whalen C, Henker B. Orlando, Fla, Academic Press, 1980, pp 221–243Google Scholar

24. Gittelman-Klein R, Klein DF, Katz S, Saraf K, Pollack E: Comparative effects of methylphenidate and thioridazine in hyperkinetic children. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:1217–1231Google Scholar

25. Wechsler D: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. New York, Psychological Corporation, 1949Google Scholar

26. Wechsler D: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised. New York, Psychological Corporation, 1974Google Scholar

27. Conners CK: A teacher rating scale for use in drug studies with children. Am J Psychiatry 1969; 126:152–156Google Scholar

28. Conners CK: Rating scales for use in drug studies with children. Psychopharmacol Bull 1973; 9:24–29Google Scholar

29. Abikoff H, Gittelman R, Klein DF: Classroom observation code for hyperactive children: a replication of validity. J Consult Clin Psychol 1980; 48:555–565Google Scholar

30. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS: National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:381–389Google Scholar

31. Mannuzza S, Klein RG: Schedule for the Assessment of Conduct, Hyperactivity, Anxiety, Mood, and Psychoactive Substances (CHAMPS). New Hyde Park, New York, Children’s Behavior Disorders Clinic, Long Island Jewish Medical Center, 1987Google Scholar

32. Cox DR: Regression models and life tables. J Royal Stat Society 1972; 34(Series B):187–220Google Scholar

33. Lynam D, Moffit TE, Stouthamer-Loeber M: Explaining the relationship between IQ and delinquency. J Abnorm Psychol 1993; 102:187–196Google Scholar

34. Chassin L, Pitts SC, DeLucia C, Todd M: A longitudinal study of children of alcoholics. J Abnorm Psychol 1999; 108:106–119Google Scholar

35. Merikangas KR, Dierker LC, Szatmari P: Psychopathology among offspring of parents with substance abuse and/or anxiety disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1998; 5:711–720Google Scholar

36. Spooner C: Causes and correlates of adolescent drug abuse and implications for treatment. Drug Alcohol Rev 1999; 18:453–475Google Scholar

37. Hollingshead AB, Redlich FC: Social Class and Mental Illness. New York, John Wiley and Sons, 1958Google Scholar

38. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied Survival Analysis. New York, John Wiley and Sons, 1999Google Scholar

39. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Abikoff H, Moulton JL III: Significance of childhood conduct problems to later development of conduct disorder among children with ADHD. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2004; 32:565–573Google Scholar

40. Castellanos FX, Lee PP, Sharp W, Jeffries NO, Greenstein DK, Clasen LS, Blumenthal JD, James RS, Ebens CL, Walter JM, Zijdenbos A, Evans AC, Giedd JN, Rapoport JL: Developmental trajectories of brain volume abnormalities in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA 2002; 288:1740–1748Google Scholar