Differences in PTSD Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors Among World Trade Center Disaster Rescue and Recovery Workers

Abstract

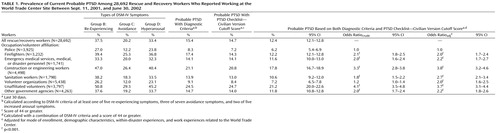

Objective: This study compared the prevalence and risk factors of current probable posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) across different occupations involved in rescue/recovery work at the World Trade Center site. Method: Rescue and recovery workers enrolled in the World Trade Center Health Registry who reported working at the World Trade Center site (N=28,962) were included in the analysis. Interviews conducted 2–3 years after the disaster included assessments of demographic characteristics, within-disaster and work experiences related to the World Trade Center, and current probable PTSD. Results: The overall prevalence of PTSD among rescue/recovery workers was 12.4%, ranging from 6.2% for police to 21.2% for unaffiliated volunteers. After adjustments, the greatest risk of developing PTSD was seen among construction/engineering workers, sanitation workers, and unaffiliated volunteers. Earlier start date and longer duration of time worked at the World Trade Center site were significant risk factors for current probable PTSD for all occupations except police, and the association between duration of time worked and current probable PTSD was strongest for those who started earlier. The prevalence of PTSD was significantly higher among those who performed tasks not common for their occupation. Conclusions: Workers and volunteers in occupations least likely to have had prior disaster training or experience were at greatest risk of PTSD. Disaster preparedness training and shift rotations to enable shorter duration of service at the site may reduce PTSD among workers and volunteers in future disasters.

First responders and others involved in rescue/recovery work following natural and manmade disasters are exposed to physical and emotional trauma. Such experiences are known to increase the risk of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (1) . Studies show that rescue/recovery responders are at increased risk for PTSD. Compared to the national prevalence of 4% for the general population (2) , the prevalence varies across rescue/recovery occupations, ranging from 5% to 32% (3 – 7) , with the highest prevalence documented in search and rescue personnel (25%) (5) , firefighters (21%) (8) , and workers with no prior disaster training (6 , 9 , 10) . It is not known whether certain occupations are intrinsically associated with higher risk for psychological distress or whether risk is associated with working outside one’s area of training. Response to the Sept. 11, 2001, attack on the World Trade Center, which involved numerous rescue/recovery organizations working for prolonged periods of time, provides a unique opportunity to better understand the burden of adverse psychological sequelae among rescue/recovery personnel.

Findings on the mental health status of rescue/recovery workers exposed to the World Trade Center disaster are slowly emerging. An assessment 2 weeks after the attack found that 22% of World Trade Center workers had acute posttraumatic stress symptoms (11) , and a study initiated 1 year after the disaster identified PTSD symptoms among 13% of workers (12) . Nearly 3 years after the attack, 10% of sanitation and construction workers continued to experience nonspecific mental health complaints (13) . Although useful, these studies have limited use for comparing the risk of PTSD across rescue/recovery occupations because they were either limited to one group or did not specify the occupation of responders included in the assessments. This study documents the prevalence and risk factors of PTSD among a variety of rescue/recovery workers responding to the World Trade Center disaster. The participants were enrollees of the World Trade Center Health Registry, a longitudinal cohort of individuals highly exposed to the World Trade Center attack. The registry includes the largest sample of rescue/recovery workers from various professional and volunteer organizations, allowing for the comparison of the prevalence of PTSD across occupations. We examined the prevalence of PTSD 2–3 years after September 11th by occupation and assessed whether occupations with less experience and training had a greater risk of developing PTSD. We also assessed whether tasks performed by workers that were inconsistent with their typical occupational roles (e.g., construction workers engaging in firefighting) were associated with an increased risk of PTSD.

Method

Cohort

The World Trade Center Health Registry is a voluntary registry of persons who were exposed to the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attack. Individuals eligible for enrollment included residents who lived near the World Trade Center site, persons who were physically in lower Manhattan during the attacks, schoolchildren and staff in lower Manhattan, and persons involved in rescue/recovery work (14 , 15) .

The eligibility criterion for this analysis was working at least one shift from Sept. 11, 2001, to June 30, 2002, at the World Trade Center site. Both active and passive recruitment methods were used to enroll rescue/recovery workers. Active recruitment involved contacting potentially eligible individuals from lists obtained through government agencies and private sectors/entities, including organizations throughout the United States known to have participated in the rescue/recovery effort. Six hundred and seventy organizations were contacted, and 144 provided lists (14) . Passive recruitment involved self-identification through a toll-free number and project website (15) . Recruitment was supported by a large-scale public outreach and media campaign. The total World Trade Center Health Registry cohort is composed of 71,437 registrants; 29,572 were rescue/recovery workers at the World Trade Center site.

Workers who did not report their employment affiliation (N=447) and those who did not respond to a sufficient number of questions to accurately screen for probable PTSD (N=433) were excluded from this analysis. The final analytic group comprised responses from 28,692 workers and covered approximately one-third of the 91,469 workers and volunteers eligible for enrollment in the World Trade Center Health Registry (14) .

Data Collection

Enrollment was from Sept. 5, 2003, to Nov. 20, 2004. Baseline interviews were conducted during enrollment. Informed consent was obtained after a complete description of the study was provided and before eligibility was determined. The mode of administration was a 30-minute computer-assisted telephone interview. Interviews with rescue/recovery workers were conducted in English (96.2%), Spanish (2.6%), and Chinese (0.3%) with real-time translation for other languages (1.2%).

During the baseline interview, rescue/recovery workers were asked with which employer or volunteer organization they were affiliated while working at the World Trade Center site. The responses were assessed by human review and assigned to one of 52 groups, which were validated by multiple raters. These groups were used to assign workers into the following occupations:

Police (N=3,925), including New York City police, Port Authority police, New York City and non-New York City sheriff’s offices, and all other non-New York City police departments

Firefighters (N=3,232), including both New York City and non-New York City fire departments

Emergency medical services/medical disaster personnel (N=1,741), including all New York City and non-New York City emergency medical services and medical organizations, disaster medical assistance teams, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and other search and rescue teams

Construction/engineering (N=4,498), including U.S. Corps of Engineers, New York City Department of Design and Construction, environmental abatement and pest and dust control companies, and utility companies

Sanitation (N=1,798), including employees from the New York City Department of Sanitation

Volunteer organizations (N=5,438), including the Red Cross, the Salvation Army, and other volunteer organizations

Unaffiliated volunteers (N=3,797), including clergy and individuals who reported occupations unrelated to rescue and recovery work (e.g., finance and insurance, real estate)

Other government agencies (N=4,263), including employees of other local, state, and federal government agencies

Demographic Characteristics

Demographic characteristics assessed for potential confounding included age, gender, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, income status, and marital status.

Within-Disaster Experiences

Experiences during the disaster (within-disaster experiences) known to increase the risk for PTSD include life threat (11 , 16) and witnessing horror (9 , 17) . Assessment of life threat among rescue/recovery workers included being caught in the dust/debris cloud that resulted from the collapse of the towers, being an occupant of World Trade Center tower 1 or 2, or sustaining an injury on September 11th. Witnessing horror was measured by creation of a dichotomous variable and was defined as witnessing any of the following: an airplane hitting the World Trade Center, a building collapsing, people running from a cloud of dust/debris, individuals being injured or killed, or people falling or jumping from the World Trade Center towers. A continuous variable of number of horrific events witnessed was not used because most who witnessed at least one witnessed multiple events.

Work Experiences Related to the World Trade Center

Workers were asked to specify the first and last dates they worked at the site and how many days they worked during each of the following time periods: on Sept. 11, 2001 (day 1); on Sept. 12, 2001 (day 2); between Sept. 13, 2001, and Sept. 17, 2001 (days 3–7); between Sept. 18, 2001, and Dec. 31, 2001 (days 8–112); and between Jan. 1, 2002, and June 30, 2002 (days 113–262). The start date was categorized into the same time periods. For workers who did not report the date they started working (3.4%), the first interval they reported working at least 1 day was assumed to be their start date. Workers were also asked to estimate how many days they worked during each time period. For the last two time periods, they were asked to estimate how many days they worked using the following time intervals: 1–2 days, 3–6 days, 7–30 days, 31–60 days, and more than 60 days. The midpoint for each time interval was used to approximate the amount of time worked during these time periods. Total duration of time worked was calculated by summing the approximated number of days worked during each time period and was verified by a sensitivity analysis based on the first and last reported dates of work. Information was also collected about specific tasks performed on “the pile” (“the pile” refers to the construction/restricted zone composed of the rubble and remains for the collapsed World Trade Center towers), including firefighting, search and rescue activities, hand digging, welding/steel cutting/torch operation, operation of heavy equipment, and light construction.

Probable PTSD

The PTSD Checklist—Civilian Version was used to assess probable PTSD (18 , 19 ; unpublished work by Weathers et al., 1993). The PTSD Checklist—Civilian Version is a self-reported 17-item symptom scale that corresponds to APA’s DSM-IV criteria and is often used when a clinical interview is not feasible (20) . The PTSD Checklist—Civilian Version assesses the full domain of PTSD symptoms in three clusters: intrusive and reexperiencing, numbing and avoidance, and hyperarousal. Each symptom was assessed as event-specific (“as a result of the World Trade Center disaster”) and current (“within the last 30 days”). As suggested by North and Pfefferbaum (21) , we refer to this outcome as current probable PTSD to acknowledge that symptoms determined through the use of a screening instrument do not necessarily indicate psychopathology.

Missing responses on the PTSD Checklist—Civilian Version were imputed for 1.6% of the workers who answered at least 80% of the questions within each symptom cluster. Imputation, which consisted of substituting the respondent’s average cluster response for missing data, resulted in no statistically significant difference in prevalence. In order to permit comparisons across studies, probable PTSD was calculated three ways: 1) using DSM-IV diagnostic criteria (the presence of at least one reexperiencing symptom, three avoidance symptoms, and two hyperarousal symptoms) (22) , 2) with a standard cutoff score of 44 (18) , and 3) with a combination of both.

Statistical Analyses

Simple and multivariable logistic regression analyses using PROC LOGISTIC in SAS, Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.), were performed to compare PTSD prevalence across occupations. Police were used as the referent category because previous studies have suggested that PTSD prevalence tends to be lowest among police (9 , 23 , 24) . Significant risk factors identified in the simple logistic regression analyses were considered for the multivariable logistic regression. To assess which variables to include in the final models, we performed forward and backward selection and calculated the chi-square from the difference in –2 log likelihood estimates for each subsequent model. We retained all variables that significantly improved model fit (p<0.05) and adjusted for mode of World Trade Center Health Registry enrollment (list recruitment versus self-identification).

Another goal of the study was to assess occupation-specific risk factors for PTSD. To accomplish this, simple logistic regression and multivariable regression analyses were performed for each occupational group. Multivariable regression analyses controlled for mode of enrollment, demographic characteristics, and within-disaster and work experiences that significantly improved model fit.

Results

The mode of World Trade Center Health Registry enrollment was significantly associated with PTSD among sanitation workers and volunteer organizations and thus was left in the model. For all other occupational groups, mode of enrollment was not significantly associated with PTSD.

Demographic Characteristics

Demographic characteristics differentially influenced PTSD risk by occupational group. Because interpretation was beyond the scope of the present study, the results are not included. The multivariable analyses controlled for demographic characteristics within each occupational group that significantly improved the model fit.

PTSD Prevalence

Table 1 presents the prevalence and odds ratios associated with current probable PTSD and symptom clusters stratified by occupation. The prevalence of current probable PTSD among all rescue/recovery workers was 12.4%. With the exception of firefighters, the prevalence of current probable PTSD using either diagnostic criteria or the PTSD Checklist—Civilian Version cutoff score was similar. The combined criteria yielded a lower prevalence in all occupations. Because this calculation was the most conservative estimate, it was used as the outcome for subsequent risk factor analyses. The prevalence of PTSD ranged from 6.2% for police to 21.2% for unaffiliated volunteers. Reexperiencing and hyperarousal were reported more frequently than avoidance symptoms.

Compared to police, the highest PTSD prevalences were found among unaffiliated volunteers (adjusted odds ratio [odds ratio adj ]=3.7) and construction/engineering (odds ratio adj =3.8). After we controlled for significant demographic, disaster, and work experiences related to the World Trade Center, the prevalence of PTSD was substantially elevated in sanitation workers (odds ratio adj =2.7) and individuals reporting affiliation with volunteer organizations (odds ratio adj =2.0).

Within-Disaster Experiences

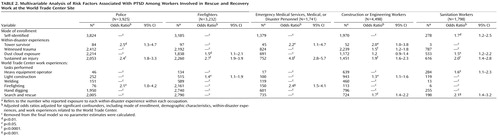

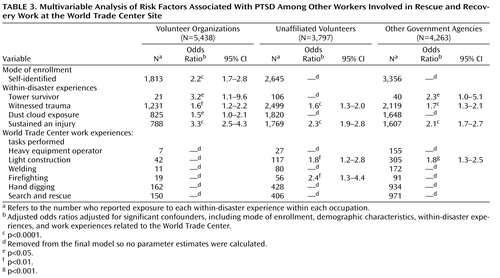

Tables 2 and 3 present the adjusted associations between within-disaster experiences and current probable PTSD stratified by occupation. Sustaining an injury was the only within-disaster experience that increased risk among all occupations and was the strongest risk factor for all occupations (odds ratios adj ranging from 1.9 to 4.0) except police and construction/engineering. Evacuating from one of the World Trade Center towers was associated with an increased risk among all occupations except firefighters; too few sanitation workers reported evacuating to analyze (N=3). All within-disaster experiences except dust cloud exposure were significant risk factors for PTSD in construction/engineering workers.

Nearly all within-disaster experiences were significant risk factors for volunteer organizations, unaffiliated volunteers, and other governmental agencies ( Table 3 ). Sustaining an injury was the strongest risk factor for both volunteer organizations and unaffiliated volunteers (odds ratios adj =3.3 and 2.3, respectively), whereas the strongest risk factor for other government agencies was evacuating from one of the towers (odds ratio adj =2.3). Dust cloud exposure was a significant risk factor in volunteer organizations only.

Work Experiences Related to the World Trade Center

The adjusted associations between work experiences related to the World Trade Center and current probable PTSD stratified by occupation are presented in Tables 2 and 3 . The relationships between tasks performed at the World Trade Center site and PTSD varied by occupation, with the strongest associations observed for tasks performed that were atypical of reported occupation. For example, firefighting was associated with a twofold increase in PTSD risk among police and emergency medical services/medical/disaster personnel, whereas performing light construction was the only task associated with PTSD among firefighters. Search and rescue was the strongest task-related risk factor among construction/engineering and sanitation workers. None of the work experiences related to the World Trade Center increased the risk for PTSD among volunteer organizations. Performing light construction work was associated with a nearly twofold increase in PTSD among unaffiliated volunteers and other government agencies. The strongest risk factor for unaffiliated volunteers was firefighting (odds ratio adj =2.4).

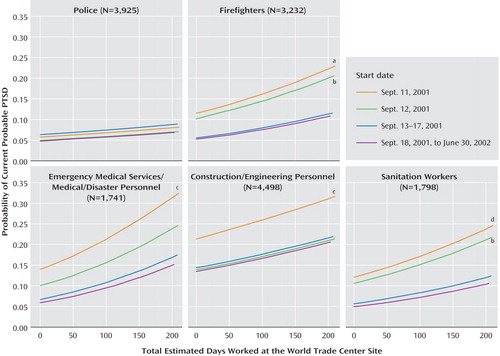

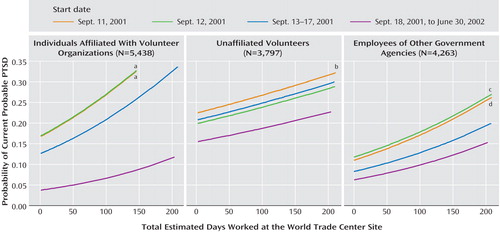

The relationship between the duration of time worked and current probable PTSD differed by occupation. Figures 1 and 2 present the association between the duration of time worked and probable PTSD stratified by the start date for each occupation. The probability of PTSD increased with longer duration of time worked at the site for all occupations except police. The probability of PTSD was also greater for those who started on September 11th compared to those who started after September 18th (odds ratios: firefighters=2.4, emergency medical services/medical/disaster personnel=2.6, construction/engineering workers=1.8, sanitation workers=2.7). The association between the duration of time worked and probable PTSD was strongest among those who started on September 11th for all occupations except police.

a p<0.001.

b p<0.05.

c p<0.0001.

d p<0.01.

a p<0.0001.

b p<0.05.

c p<0.001.

d p<0.01.

Starting work on September 11th also increased the association between the duration of time worked and the probability of PTSD for the other workers (odds ratios: volunteer organizations=5.1, unaffiliated volunteers=1.6, other government agencies=1.9). The association for starting on September 12th was nearly the same as starting on September 11th in the affiliated and unaffiliated volunteers (odds ratios=5.2 and 1.4, respectively).

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to compare workers from different occupations responding to the same disaster and the first, to our knowledge, to analyze this for the World Trade Center attacks, the largest manmade disaster in U.S. history. The prevalence of PTSD and associated risk factors differed substantially, nearly fourfold across occupations. Workers in occupations less prepared for the type of disaster work required at the World Trade Center site, such as firefighting and search and rescue, were more likely to develop PTSD; the highest rates were documented among volunteers, construction/engineering workers, and sanitation workers. Furthermore, workers who engaged in tasks outside of their training were also at increased risk. When examined by task, the rates of PTSD were highest among emergency medical services/medical/disaster personnel who engaged in firefighting and sanitation workers who engaged in search and rescue. In contrast, few work experiences at the World Trade Center were associated with risk among groups for which prior training and preparedness is most likely to be heterogeneous, and the strongest risk factors for these groups were within-disaster experiences.

Our finding that the prevalence of PTSD varied by occupation is consistent with the previous literature on disaster responders (3 – 7) and suggests that prior training or experience may protect against the psychological distress associated with disaster work, as suggested by others. Potential explanations for why prior training protects against PTSD include an increased sense of self-efficacy or internal locus of control and the satisfaction of applying previous training to successfully fulfill duties (23 , 25 , 26) .

Among occupations most likely to have had prior training, emergency medical services/medical/disaster personnel and firefighters were twice as likely to have current probable PTSD as police. Other studies of police involved in rescue/recovery work have also reported a lower prevalence of psychological distress (23 , 27) and probable PTSD (24) . Police screening procedures may result in selection of a more psychologically resilient workforce. It is also possible that police officers are more likely to underreport symptoms of psychological distress for fear that they will judged as unable to perform their job responsibilities. Firefighters and emergency medical services personnel may also underreport symptoms; however, it is more likely among police officers because compromised psychological health is associated with graver consequences in an environment where carrying a firearm is a daily requirement.

For the World Trade Center disaster, bereavement (28) and self-identification with the victims (29) may have also contributed to the difference in PTSD prevalence. Firefighters lost six times as many comrades as the police (30) , and Fire Department of New York funerals continued through September 2003. An assessment 7–13 weeks after Hurricane Katrina, however, documented no disparity in the prevalence of PTSD among police and firefighters (19% and 22%, respectively) (31) . These findings may be explained by other experiences known to increase risk for psychological distress, such as civil disobedience, hostility, and aggression toward police (32) , all widely depicted in post-Katrina media coverage.

Lack of access to mental health services may also account for increased risk of PTSD among sanitation workers, construction/engineering workers, and unaffiliated volunteers. Although our survey did not directly assess this, sanitation workers, medical personnel, and other volunteers were excluded from the World Trade Center injury and illness surveillance programs established in local hospitals after the attack to assist rescue/recovery workers injured while working at the site because it was believed that they were not directly involved in rescue/recovery operations (33) . Furthermore, World Trade Center firefighters and police had additional access to mental health support and critical incident stress management services through other organizations. To our knowledge, no comparable services were established for construction/engineering and sanitation workers.

It is also possible that lack of recognition is partially responsible for an increase in psychological distress. Construction and sanitation World Trade Center workers from another study reported feeling that their psychological distress was prolonged because unlike other World Trade Center workers, they did not receive recognition for their efforts, preventing them from obtaining closure (13) .

Among the range of traumatizing experiences during the disaster, being injured on September 11th significantly increased the risk of PTSD for all workers, whereas witnessing trauma was a significant risk factor only for construction/engineering workers, volunteer organizations, unaffiliated volunteers, and other government agencies. One potential explanation for this finding is that previous exposure to trauma during the daily job responsibilities required of police, firefighters, and emergency medical services personnel may have desensitized them to the deleterious effects of witnessing trauma. In contrast, sustaining an injury is a measure of personal life threat, which is less likely to be modified by prior experiences.

As was found among responders to the Oklahoma City bombing (25) , the duration of work at the disaster site was associated with PTSD. For all occupations except police, the probability of PTSD was elevated for those who worked for more than 3 months. Stratified analyses also revealed that the relationship between time worked at the site and the probability of PTSD was strongest for those who started on September 11th, when exposure to trauma and risk of injury was greatest in all groups except for police. It is possible that the lack of association between the start date, duration of work, and PTSD among police may be related to tasks performed because they were responsible for patrolling the perimeter and less likely to have been involved with tasks on the pile for which they had no prior training. Supporting this argument is evidence from our cohort that few police reported operating heavy equipment (1.2%), performing light construction work (6.9%), or firefighting (1.9%) at the World Trade Center site.

A few limitations of this study must be noted. First, among sanitation workers and volunteer organizations, mode of enrollment was significantly associated with PTSD. Individuals within these groups who self-identified into the registry were more likely to be diagnosed with probable PTSD. This raises the possibility of reporting bias and overestimation of the mental health impact of the event; however, we appropriately controlled for this in each of the multivariable analyses across all occupations, and our findings remained the same. Second, individuals from hundreds of different organizations responded to the disaster and initiated work at varying time periods, and ascertaining the representativeness of this cohort is challenging. An assessment of coverage and enrollment rates found that approximately one-third of those eligible enrolled in the World Trade Center Health Registry with coverage varying among organizations: the enrollment rate was 68.9% for the New York City Police Department, 50.4% for the New York City Department of Sanitation, and 23.5% for the Fire Department of New York (34) . Although coverage for some groups was modest, for the five major occupational groups included in this study, we successfully recruited ample numbers from both self-enrollment and employee lists to examine differences in prevalence and risk factors. Third, degree of previous training and professional experience were not directly assessed but rather inferred based on occupation. However, the observation that tasks inconsistent with typical occupational roles were significant risk factors for PTSD provides greater confidence in our assumptions about prior training. Examination of characteristics such as mental health history and social support and mental health care use are also necessary to further elucidate the relationship between disaster work and PTSD. Such assessments are planned for the first follow-up survey of World Trade Center Health Registry registrants. Finally, it is important to note that among some of the groups assessed, such as volunteer workers and responders from other government agencies, individuals most likely self-selected for participation in rescue/recovery work. It is possible that some persons who self-selected to respond were not well screened compared to police and firemen and may have been at increased risk for PTSD.

The World Trade Center Health Registry is the largest disaster registry in U.S. history, and the rescue/recovery worker sample includes the largest number of workers from multiple occupations exposed to the same disaster. Current probable PTSD was identified with a standardized, well-validated assessment, providing confidence in our prevalence estimates and enabling comparisons across studies.

The results from the present analysis suggest that rescue/recovery workers who responded to the September 11th disaster continue to experience substantial psychological distress years later. Our findings demonstrate a need for targeted interventions specific to the diversity of workers who respond to large disasters to reduce the psychological burden associated with participation. Disaster preparedness training and shift rotations to enable a shorter duration of service at the site may reduce PTSD among workers and volunteers in future disasters.

1. Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, Byrne CM, Diaz E, Kaniasty K: 60,000 disaster victims speak, part I: an empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry 2002; 65:207–260Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Chin WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:617–627Google Scholar

3. Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, Wang L: Acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in disaster or rescue workers. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1370–1376Google Scholar

4. Epstein RS, Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ: Posttraumatic stress disorder following an air disaster: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:934–938Google Scholar

5. Ozen S, Aytekin S: Frequency of PTSD in a group of search and rescue workers two months after 2003 Bingol (Turkey) earthquake. J Nerv Ment Dis 2004; 192:573–575Google Scholar

6. Guo U, Chen C, Lu M, Tan HK, Lee H, Wang T: Posttraumatic stress disorder among professional and non-professional rescuers involved in an earthquake in Taiwan. Psychiatry Res 2004; 127:35–41Google Scholar

7. North CS, Tivis L, McMillen JC, Pfefferbaum B, Spitznagel EL, Cox J, Nixon S, Bunch KP, Smith EM: Psychiatric disorders in rescue workers after the Oklahoma City bombing. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:857–859Google Scholar

8. Chang C, Lee L, Connor KM, Davidson JRT, Jeffries K, Lai T: Posttraumatic distress and coping strategies among rescue workers after an earthquake. J Nerv Ment Dis 2003; 191:391–398Google Scholar

9. Marmar CR, Weiss DS, Metzler TJ, Ronfeldt HM, Foreman C: Stress responses of emergency services personnel to the Loma Prieta earthquake interstate 880 freeway collapse and control traumatic incidents. J Trauma Stress 1996; 9:63–85Google Scholar

10. Dyregrov A, Kristoffersen JI, Gjestad R: Voluntary and professional disaster-workers: similarities and differences in reactions. J Trauma Stress 1996; 9:541–555Google Scholar

11. Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, Reeves J, Shigemura J, Grieger T: Perceived safety in disaster workers following 9/11. J Nerv Ment Dis 2006; 194:61–63Google Scholar

12. Smith RP, Katz CL, Holmes A, Herbert R, Levin S, Moline J, Landsbergis P, Stevenson L, North CS, Larkin GL, Baron S, Hurrell JJ: Mental health status of World Trade Center rescue and recovery workers and volunteers—New York City, July 2002–Aug 2004. MMWR 2004; 53:812–815Google Scholar

13. Johnson SB, Langlieb AM, Teret SP, Gross R, Schwab M, Massa J, Ashwell L, Geyh AS: Rethinking first response: effects of the clean up and recovery effort on workers at the World Trade Center disaster site. J Occup Environ Med 2005; 47:386–391Google Scholar

14. Dolan M, Murphy J, Thalji L, Pulliam P: World Trade Center Health Registry: Sample Building and Denominator Estimation. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, RTI project number 08692, contract number 200–2002-M-00836, 2006Google Scholar

15. Pulliam P, Thalji L, DiGrande L, Perrin M, Walker D, Wu D, Dolan M, Triplett S, Dean E, Peele P, Brackbill RM: World Trade Center Health Registry: Data File User’s Manual. New York, RTI International, New York Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, 2006Google Scholar

16. Marmar CR, Weiss DS, Metzler TJ, Delucchi K: Characteristics of emergency services personnel related to peritraumatic dissociation during critical incident exposure. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153(7 suppl):94–102Google Scholar

17. Brandt GT, Fullerton CS, Saltzgaber L: Disasters: psychological responses in health care providers and rescue workers. Nordic J Psychiatry 1995; 49:89–94Google Scholar

18. Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley RC, Forneris CA: Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther 1996; 34:669–673Google Scholar

19. Ruggiero KJ, Del Ben K, Scotti JR, Rabalais AE: Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist—Civilian Version. J Trauma Stress 2003; 16:495–502Google Scholar

20. Dobie DJ, Kivlahan DR, Maynard CR, McFall M, Epler AJ, Bradley KA: Screening for post-traumatic stress disorder in female veteran’s affairs patients: validation of the PTSD Checklist. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2002; 24:367–374Google Scholar

21. North CS, Pfefferbaum B: Research on the mental health effects of terrorism. JAMA 2002; 288:633–636Google Scholar

22. Smith MY, Redd W, DuHamel K, Vickberg SJ, Ricketts P: Validation of the PTSD Checklist—Civilian Version in survivors of bone marrow transplantation. J Trauma Stress 1999; 12:485–499Google Scholar

23. Alexander DA, Wells A: Reactions of police officers to body-handling after a major disaster. Br J Psychiatry 1991; 159:547–555Google Scholar

24. Renck B, Weisæth L, Skarbö S: Stress reactions in police officers after a disaster rescue operation. Nordic J Psychiatry 2002; 56:7–14Google Scholar

25. North CS, Tivis L, McMillen JC, Pfefferbaum B, Cox J, Spitznagel EL, Bunch KP, Schorr J, Smith EM: Coping, functioning, and adjustment of rescue workers after the Oklahoma City bombing. J Trauma Stress 2002; 15:171–175Google Scholar

26. Alvarez J, Hunt M: Risk and resilience in canine search and rescue handlers after 9/11. J Trauma Stress 2005; 18:497–505Google Scholar

27. Alexander DA: Stress among police body handlers: a long-term follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 163:806–808Google Scholar

28. Pivar IL, Field NP: Unresolved grief in combat veterans with PTSD. J Anxiety Disord 2004; 18:745–755Google Scholar

29. Ursano RJ, Fullerton CS, Vance K, Kao TC: Posttraumatic stress disorder and identification in disaster workers. Am J Psych 1999; 156:353–359Google Scholar

30. Death, destruction, charity, salvation, war, money, real estate, spouses, babies, and other September 11 statistics. New York Magazine. http://www.newyorkmetro.com/news/articles/wtc/1year/numbers.htmGoogle Scholar

31. Bernard BP, Driscoll RJ: Health hazard evaluation of police officers and firefighters after Hurricane Katrina—New Orleans, La, Oct 17–18 and Nov 30–Dec 5, 2005. MMWR 2006; 55:456–458Google Scholar

32. Sims A, Sims D: The phenomenology of post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychopathology 1998; 31:96–112Google Scholar

33. Berrios-Torres SI, Greenko JA, Phillips M, Miller JR, Treadwell T, Ikeda RM: World Trade Center rescue recovery worker injury and illness surveillance, NY, 2001. Am J Prev Med 2003; 25:79–87Google Scholar

34. Murphy J: World Trade Center Health Registry Enrollment and Coverage Report. Research Triangle Park, NC, RTI International, RTI project number 08692, contract number 200–2002-M-00836, 2006Google Scholar