Issues for DSM-V: How Should Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders Be Classified?

There are conflicting views regarding the classification of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in the next edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (1 , 2) . In an attempt to identify areas of expert consensus/disagreement and thus help steer research efforts toward DSM-V, we conducted a worldwide survey among OCD experts. The e-mail addresses of 303 corresponding authors of papers on OCD published between 1996 and 2006 were extracted from electronic databases. A survey asking contentious questions regarding the classification of OCD was piloted and improved (for additional details, see the data supplement accompanying the online version of this editorial) before being e-mailed to the experts. One hundred eighty-seven surveys were received, constituting a geographically representative cohort of international OCD experts (108 psychiatrists, 69 psychologists, 10 other).

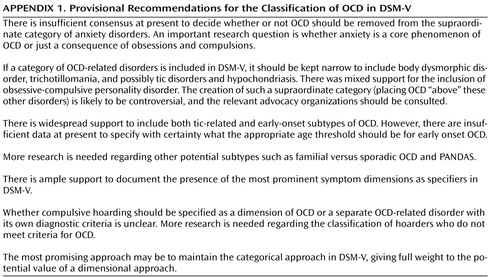

Regarding whether OCD should be removed from the current supraordinate category of anxiety disorders, approximately 60% agreed and 40% disagreed. There was a significant difference (χ 2 =17.9, df=2, p<0.001) in opinion between psychiatrists (75% agreed) and other professionals (40%–45% agreed). The most frequent reason for agreeing was that obsessions and compulsions, rather than anxiety, are the fundamental features of the disorder. The main reasons for disagreeing were that OCD and other anxiety disorders respond to similar treatments and tend to co-occur (see the data supplement).

The survey also revealed that if a new OCD spectrum disorders category is created, the expert consensus is to keep it narrow and only include body dysmorphic disorder (72% agree), trichotillomania (70% agree), and possibly tic disorders (61% agree) and hypochondriasis (57% agree). There was mixed support (45% agree) for the inclusion of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. A majority of experts disagreed with the inclusion of other disorders classified elsewhere in DSM-IV-TR (see the data supplement).

Regarding the specification of possible OCD subtypes, there was ample support for tic-related (81% agree) and early onset subtypes, although the experts disagreed regarding the definition of early onset OCD: before age 10 (66% agree) or before age 18 (49% agree). There was some support for familial versus sporadic (61.5% agree) and PANDAS (53% agree) subtypes.

A majority of experts (89%) agreed that OCD is heterogeneous, that symptoms are experienced within multiple potentially overlapping dimensions (3) , and that it will be important to document their presence as specifiers in DSM-V. There was ample support for the specification of five symptom dimensions (see the data supplement): contamination/cleaning (92%), symmetry/order/repeating/counting (87%), hoarding (87%), harm (aggressive) obsessions and checking (85%), and sexual and religious obsessions (69%).

Few would disagree that psychiatric classification should “carve nature at the joints” where possible, although this is rare. Classifications are fictions imposed on a complex world to understand it and manage it (4) . They must be useful to both researchers and clinicians (5) . The results of the current survey led us to compile a set of recommendations, which will hopefully serve both these functions ( Appendix 1 ).

1. Abramowitz JS, Deacon BJ: The OCD spectrum: a closer look at the arguments and the data, in Concepts and Controversies in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Edited by Abramowitz JS, Houts AC. New York, Springer, pp 141–149Google Scholar

2. Bartz JA, Hollander E: Is obsessive-compulsive disorder an anxiety disorder? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2006; 30:338–352Google Scholar

3. Mataix-Cols D, Rosario-Campos MC, Leckman JF: A multidimensional model of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:228–238Google Scholar

4. Marks IM, Mataix-Cols D: Diagnosis and classification of phobias: a review, in Phobias: WPA Series, Evidence and Experience in Psychiatry, vol 7. Edited by Maj M, Akiskal HS, Lopez-Ibor JJ, Okasha A. London, John Wiley and Sons, 2004, pp 1–32Google Scholar

5. First MB: Beyond clinical utility: broadening the DSM-V research appendix to include alternative diagnostic constructs. Am J Psychatry 2006; 163:1679–1681Google Scholar