The Subsyndromal Phenomenology of Borderline Personality Disorder: A 10-Year Follow-Up Study

Abstract

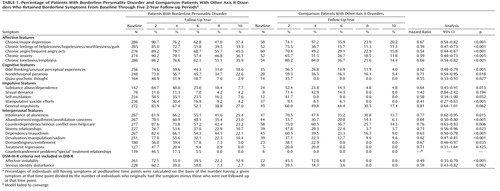

Objective: The purpose of this study was to characterize the course of 24 symptoms of borderline personality disorder in terms of time to remission. Method: The borderline psychopathology of 362 patients with personality disorders, all recruited during inpatient stays, was assessed using two semistructured interviews of proven reliability. Of these, 290 patients met DSM-III-R criteria as well as Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines criteria for borderline personality disorder, and 72 met DSM-III-R criteria for another axis II disorder. Over 85% of the patients were reinterviewed at five distinct 2-year follow-up waves by interviewers blind to all previously collected information. Results: Among borderline patients, 12 of the 24 symptoms studied showed patterns of sharp decline over time and were reported at 10-year follow-up by less than 15% of the patients who reported them at baseline. The other 12 symptoms showed patterns of substantial but less dramatic decline over the follow-up period. Symptoms reflecting core areas of impulsivity (e.g., self-mutilation and suicide efforts) and active attempts to manage interpersonal difficulties (e.g., problems with demandingness/entitlement and serious treatment regressions) seemed to resolve the most quickly. In contrast, affective symptoms reflecting areas of chronic dysphoria (e.g., anger and loneliness/emptiness) and interpersonal symptoms reflecting abandonment and dependency issues (e.g., intolerance of aloneness and counterdependency problems) seemed to be the most stable. Conclusions: The results suggest that borderline personality disorder may consist of both symptoms that are manifestations of acute illness and symptoms that represent more enduring aspects of the disorder.

Numerous cross-sectional divisions of the symptoms of borderline personality disorder have been proposed, some reflecting clinical experience (1 , 2) and others derived through statistical analyses (3 – 6) . All of these classifications have sought to bring greater conceptual clarity to the borderline diagnosis by grouping symptoms into clinically coherent sectors of psychopathology.

The results of two longitudinal studies (7 – 9) suggest that some borderline symptoms resolve more quickly than others. This finding has led to two distinct but overlapping conceptualizations of the nature of the symptoms of the disorder. In the first, based on 6 years of prospective follow-up in the McLean Study of Adult Development, some of the 24 symptoms of borderline personality disorder studied were described as acute and others as temperamental (9 , 10) . In this “complex” model of borderline psychopathology, acute symptoms, which are seen as akin to the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, seem to resolve relatively rapidly, are the best markers for the disorder (2) , and are often the immediate reason that costly forms of treatment, such as psychiatric hospitalization, are needed. In contrast, temperamental symptoms (so named because results of longitudinal studies of temperament suggest that temperament is innate but not immutable [11] ) seem to resolve more slowly, are not specific to borderline personality disorder, and are closely associated with ongoing psychosocial impairment. They are seen as akin to the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Among the symptoms studied, the prevalence of five core borderline symptoms was found to decline with particular rapidity: quasi-psychotic thought, self-mutilation, help-seeking suicide efforts, treatment regressions, and countertransference problems. In contrast, feelings of depression, anger, and loneliness/emptiness were the most stable symptoms.

In the second conceptualization, the 2-year results of the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study were interpreted to suggest a similar model of borderline (and other axis II) psychopathology (12 , 13) . This “hybrid” model divides symptoms into symptomatic behaviors and traits. Traits are seen as fundamental and enduring. Symptomatic behaviors, in contrast, are seen as both more episodic and reactive in nature, arising as a means of coping with or defending against these more core propensities or traits. Among the nine DSM-IV symptoms of borderline personality disorder studied, impulsivity and anger were found to be the most stable symptoms, while abandonment fears and physically self-destructive acts were found to be the least stable.

Given the relatively brief follow-up periods in those two studies, however, the long-term course of the symptoms of borderline personality disorder remains unclear.

This is the first study to assess the time to remission of borderline personality disorder symptoms over 10 years of prospective follow-up. While our earlier study involving the prevalence of 24 borderline symptoms over 6 years of follow-up provided preliminary data on the course of these symptoms, the longer follow-up period of the current study, along with a focus on time to remission, provides a sufficient time frame and the appropriate analytic strategy to assess the rapidity of symptom resolution for each of the symptoms of this slowly evolving disorder. This is also the first study to assess speed of symptom resolution as a component of a theoretical model of the nature of the symptoms of borderline personality disorder—a “complex” model that involves the specificity and the social consequences of symptoms as well as their time to remission.

Method

All participants were initially inpatients at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass. All were between the ages of 18 and 35, had a known or estimated IQ ≥71, were fluent English speakers, and had no history or current symptoms of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar I disorder, or an organic condition that could cause psychiatric symptoms. The study procedures were explained, and written informed consent was obtained. Each patient then underwent a thorough diagnostic assessment by a master’s-level interviewer who was blind to the patient’s clinical diagnoses. Three semistructured diagnostic interviews were administered: the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) (14) , the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R) (15) , and the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (DIPD-R) (16) . The interrater and test-retest reliability of all three of these measures have been found to be good to excellent (17 , 18) .

At each of five follow-up waves 24 months apart, axis I and II psychopathology was reassessed by staff members blind to baseline diagnoses. Informed consent was obtained again in each case, and the diagnostic battery was readministered. The follow-up interrater reliability (i.e., within one generation of follow-up raters) and follow-up longitudinal reliability (from one generation of raters to the next) of these three measures have also been found to be good to excellent (17 , 18) .

The time to remission of a symptom was defined in terms of the follow-up wave in which that symptom was first observed to have remitted. Thus, time to remission of a symptom would be 2 years for persons who first achieved remission of that symptom during the first follow-up period (the first 24 months after baseline), 4 years for those who first achieved remission of the symptom during the second follow-up period, and so on.

To compare time to remission between patient groups, we used a Cox proportional hazards model that accounted for discrete failure times by using the exact partial likelihood (equivalent to conditional logistic regression where groups are defined by the risk sets and the outcome is remission), as implemented in Stata, release 9 (Stata Corp., College Station, Tex.). Age, sex, and race were included in these models as covariates. Alpha was set at 0.05, two-tailed.

Results

A total of 290 patients met both DIB-R and DSM-III-R criteria for borderline personality disorder, and 72 patients who did not meet either criteria set for borderline personality disorder met DSM-III-R criteria for at least one other axis II disorder. Baseline demographic data have been reported previously (9) . Briefly, of the overall sample of 362 patients, 77% (N=279) were female and 87% (N=315) were white. The sample’s mean age was 27 years (SD=6.3), the mean socioeconomic status on the Hollingshead-Redlich Scale was 3.3 (SD=1.5) (where 1=highest and 5=lowest), and the mean Global Assessment of Functioning Scale score was 39.8 (SD=7.8), indicating major impairment in several areas, such as work or school, family relations, judgment, thinking, or mood.

Attrition was low, with 85% (N=309) of patients in the overall sample reinterviewed at all five follow-up waves. Of the original 290 borderline patients, 275 were reinterviewed at 2 years, 269 at 4 years, 264 at 6 years, 255 at 8 years, and 249 at 10 years. Of the original 72 axis II comparison patients, 67 were reinterviewed at 2 years, 64 at 4 years, 63 at 6 years, 61 at 8 years, and 60 at 10 years. Of the 41 borderline patients (14%) who were no longer in the study at the 10-year assessment, 12 committed suicide, six died of other causes, 10 discontinued their participation, and 13 were lost to follow-up. Of the 12 axis II comparison patients (17%) no longer participating, one committed suicide, four discontinued their participation, and seven were lost to follow-up.

No significant differences were found in key baseline demographic and clinical variables between the borderline patients who remained in the study through all five follow-up periods and those who did not. In the axis II comparison group, those who remained in the study were several years older on average than those who did not (mean=28.0 years [SD=8.1] versus 21.9 years [SD=5.3], respectively; t=2.499, df=70, p=0.015).

We have previously reported on remission of the borderline diagnosis itself (9 , 19) . We found that 88% of borderline patients who had at least one follow-up interview over the 10-year follow-up period (242 of 275 patients) had a remission of the disorder (19) . (Remission was defined as no longer meeting either DIB-R or DSM-III-R criteria for borderline personality disorder.)

As Table 1 shows, for each of the 24 symptoms studied, the percentage of initially symptomatic patients in both groups who exhibited the symptom continuously throughout the follow-up intervals declined substantially over time, although borderline patients had a significantly longer time to remission on average than the axis II comparison group for 19 of these symptoms. For four of the five symptoms for which the hazard ratio was not statistically significant (sexual deviance, self-mutilation, treatment regressions, and countertransference problems), the comparison group had a low baseline prevalence, and thus the absence of a significant difference for these symptoms may reflect a lack of statistical power (that is, type II errors). For the fifth nonsignificant symptom, general impulsivity, the overall rates of remission were similar for both groups of patients.

We defined acute symptoms as those that had a remission rate exceeding 60% at the 6-year follow-up and exceeding 85% at the 10-year follow-up; temperamental symptoms were defined as those with remission rates below these thresholds. We chose these cutoffs for acute symptoms because they characterized the course of the borderline symptoms that declined the most rapidly in our previous study of the subsyndromal phenomenology of borderline personality disorder—that is, symptoms that seemed to represent aspects of acute illness (9) .

Using this set of guidelines, 12 symptoms were found to be acute and 12 temperamental. Those identified as acute were quasi-psychotic thought, substance abuse/dependence, sexual deviance (mostly promiscuity), self-mutilation, manipulative suicide efforts, stormy relationships, devaluation/manipulation/sadism, demandingness/entitlement, treatment regressions, countertransference problems/“special” treatment relationships, affective instability, and serious identity disturbance. The symptoms identified as temperamental were chronic feelings of depression, helplessness/hopelessness/worthlessness/guilt, anger, anxiety, and loneliness/emptiness; odd thinking/unusual perceptual experiences (e.g., overvalued ideas and depersonalization); nondelusional paranoia; general impulsivity (e.g., eating binges, spending sprees, and reckless driving); intolerance of aloneness; abandonment/engulfment/annihilation concerns; counterdependency/serious conflict over help/care; and dependency/masochism.

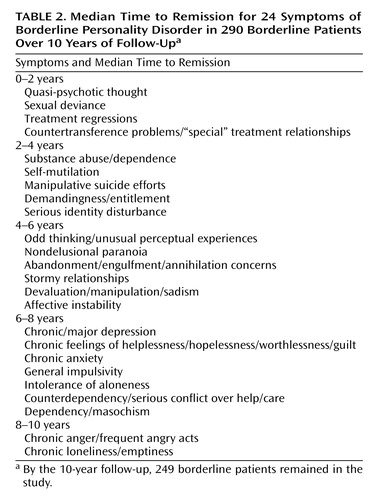

Given the conceptual and clinical nature of these analyses, we also analyzed the 24 symptoms by their median time to remission. As Table 2 shows, between baseline and the 4-year follow-up, 50% of patients first achieved remission of nine symptoms. Likewise, between the 6-year and 10-year follow-ups, 50% of patients first achieved a remission of nine other symptoms. The first group of nine symptoms were among those we characterized as acute, and the other group of nine were among those we characterized as temperamental. We also found a group of six symptoms whose median time to remission fell between the 4- and 6-year follow-ups. Three of these symptoms had been characterized as acute in the first part of our analysis (stormy relationships, devaluation/manipulation/sadism, and affective instability), and three others had previously been characterized as temperamental (odd thinking/unusual perceptual experiences, nondelusional paranoia, and abandonment/engulfment/annihilation concerns). Overall, these results are consistent with three-quarters of our findings on symptom type.

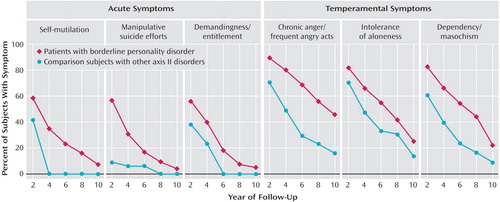

Figure 1 illustrates the trajectories for both groups in selected symptoms within the symptom categories listed in the table.

Discussion

Two main findings emerge from this study. The first is that one-half of the 24 symptoms we studied declined so substantially over time that less than 15% of subjects who exhibited them at baseline still exhibited them at the 10-year follow-up. These 12 symptoms encompassed all four sectors of borderline psychopathology detailed in the DIB-R or reflected in DSM-III-R criteria for borderline personality disorder. In the affective realm, the DSM-III-R criterion of affective instability achieved this rapid a time to remission. In the cognitive realm, both quasi-psychotic thought and serious identity disturbance remitted at this rapid a rate. (Identity disturbance was included as a cognitive symptom because it is based on false perceptions of the self, such as “I am bad” or “I am damaged beyond repair.”) In terms of forms of impulsivity, substance abuse/dependence, promiscuity, self-mutilation, and help-seeking suicide efforts remitted relatively rapidly. In the interpersonal realm, stormy relationships, devaluation/manipulation/sadism, demandingness/entitlement, serious treatment regressions, and countertransference problems/“special” treatment relationships all remitted relatively quickly.

The second main finding is that the other 12 symptoms studied declined less substantially, with about 20%–40% of borderline patients who exhibited them at baseline still exhibiting them at 10-year follow-up. These 12 symptoms also encompassed all four sectors of borderline psychopathology detailed in the DIB-R. In the affective realm, all five forms of chronic dysphoria studied demonstrated a relatively slow time to remission. For example, intense anger was still experienced after 10 years by more than 45% of borderline patients who had this symptom at their index admission. In the cognitive realm, both odd thinking/unusual perceptual experiences and nondelusional paranoia were relatively slow to remit. In the realm of impulsivity, only general impulsivity, most commonly some form of disordered eating, spending sprees, or reckless driving, remained relatively common after 10 years of prospective follow-up. Four interpersonal symptoms were also relatively slow to remit: intolerance of aloneness, abandonment/engulfment/annihilation concerns, counterdependency, and dependency/masochism.

This division makes conceptual sense. Most acute symptoms either reflect core areas of impulsivity (e.g., self-mutilation and help-seeking suicide efforts) or active attempts to manage interpersonal difficulties (e.g., problems with demandingness/entitlement and serious treatment regressions). In contrast, most temperamental symptoms seem to be either affective symptoms reflecting areas of chronic dysphoria (e.g., anger and loneliness/emptiness) or interpersonal symptoms reflecting abandonment and dependency issues (e.g., intolerance of aloneness and counterdependency problems). Looked at another way, most acute symptoms seem to have an active, even assertive, component, while most temperamental symptoms seem to reflect a certain degree of fearfulness and passivity.

Twice as many borderline symptoms seemed to resolve with relative rapidity in this study as in our previous study of the course of symptoms (9) . This difference is not surprising given that in this study we assessed time to remission of symptoms over 10 years of prospective follow-up, while in our previous study we detailed the percentage of patients exhibiting each symptom at baseline and at each of three 2-year follow-up periods.

Our 2-year survival rates for six of the nine DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder are roughly the same as those found in the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (12) . However, three other criteria seemed to resolve more slowly in the McLean Study of Adult Development than in the Collaborative Longitudinal study: anger, emptiness, and abandonment fears. Differences in survival rates of emptiness and abandonment fears may be due to the fact that the DIB-R assesses a broader construct than DSM; for example, in the DIB-R, intolerance of aloneness includes dysphoric affects that arise in response to being alone as well as the DSM-IV criterion of frantic efforts to avoid abandonment. The difference in time to remission of anger may be due to the fact that participants in the McLean study were more seriously ill at baseline than those in the Collaborative Longitudinal study.

Taken together, the results of this study suggest that borderline personality disorder may consist of both symptoms that are manifestations of acute illness and symptoms that represent more enduring aspects of the disorder. These findings may have implications for clinical care. The two psychosocial treatments for borderline personality disorder that have demonstrated efficacy, dialectical behavioral therapy (20) and mentalization-based therapy (21) , have been proven efficacious primarily for the treatment of what we have termed the acute symptoms of the disorder. However, clinical experience suggests that temperamental symptoms, such as chronic anger and undue dependency, may seriously interfere with the attainment of good psychosocial functioning. Despite this widely observed phenomenon, no psychosocial treatment has been specifically developed to treat the temperamental symptoms of borderline personality disorder. In fact, many psychotherapies end before these less obviously disruptive symptoms can be addressed. It would be useful to develop time-limited therapies to help patients quicken time to remission of these troublesome symptoms or at least cope with them more effectively. Indeed, one could argue that these more focused treatments should start at the same time as those aimed at more acute symptoms, particularly given that these symptoms seem both more resistant to change and, in our clinical experience, more connected to ongoing psychosocial impairment. This would dramatically change the focus of the treatment that many borderline patients receive, giving their temperamental symptoms the same importance as their acute symptoms, both in the patients’ view and in that of the mental health professionals treating them. For example, getting a job by overcoming dependency problems might be as much an initial goal of treatment as trying to be less demanding. In a similar vein, making friends as a way to deal with intolerance of aloneness might be as important a treatment goal in a new therapy as ceasing to make suicide threats.

This recognition of the importance of what we have termed temperamental symptoms could also lead to an examination of the relationship between the various temperamental symptoms and psychosocial impairment. For example, most mental health professionals believe that the chronic dysphoria of many borderline patients interferes with their psychosocial adjustment. It might also be true that patients’ social isolation and lack of structure perpetuates or even exacerbates their deeply held feelings of distress and unhappiness. These competing views have different treatment implications. The former is associated with the aggressive pharmacotherapy used in treating many borderline patients (22) , while the latter suggests the possible usefulness of psychotherapies that incorporate elements of social coaching and vocational counseling.

These findings may also have nosological implications. A number of theoreticians have called for replacing the signs and symptoms that have long characterized descriptions of borderline psychopathology with continuous measures of normal personality traits, particularly neuroticism (23) . In this view, personality disorders are extreme variants of normal personality. They are also seen as stable, if not chronic, disorders. Yet, most of the symptoms of borderline personality disorder that we view as acute have no counterpart in normal personality. For example, very few healthy people cut themselves to contain their anger or feel more alive, or repeatedly threaten to take their own lives to convey the desperation and aloneness they feel. In addition, the results of this study suggest that fully half of the symptoms of borderline personality disorder resolve almost completely with time and the other half show marked improvement. Adopting a set of diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder based on the theory-driven expectation of symptomatic stability rather than the empirical observation of symptomatic improvement may needlessly discourage clinicians, patients, and their families. It also runs contrary to the emerging clinical consensus that borderline personality disorder is a treatable disorder with a relatively good prognosis.

The main limitation of this study is that all participants were initially inpatients. It may be that the symptoms of borderline personality disorder resolve more quickly for less severely ill patients. A second limitation is that most of the patients in the study were in some form of treatment over time (22) , and hence the results may not apply to untreated patients (in either the borderline or the comparison group).

While overall our results and the results of the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study seem to suggest that there are two types of borderline symptoms, six of the borderline symptoms we studied did not fit cleanly into either of these symptom groups when median time to remission was used to analyze our data. This may be so because they actually are neither acute nor temperamental in nature and may represent a third or intermediate group of symptoms. It may also be so because assessing the nature of symptoms based on median time to remission may not reveal important conceptual and clinical differences. Until our results are replicated, our findings concerning symptom types, particularly the six symptoms that may fall into an intermediate category, must be considered preliminary.

1. Gunderson JG, Singer MT: Defining borderline patients: an overview. Am J Psychiatry 1975; 132:1–10Google Scholar

2. Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL: Discriminating borderline personality disorder from other axis II disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:161–167Google Scholar

3. Clarkin J, Hull JW, Hurt SW: Factor structure of borderline personality disorder criteria. J Personal Disord 1993; 7:137–143Google Scholar

4. Fossati A, Maffei C, Bagnato M, Donati D, Namia D, Novella L: Latent structure analysis of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder criteria. Compr Psychiatry 1999; 40:72–79Google Scholar

5. Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, McGlashan TH: Factor analysis of the DSM-III-R borderline personality disorder criteria in psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1629–1633Google Scholar

6. Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, Morey LC, Bender DS, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Stout RL, Zanarini MC, McGlashan TH: Confirmatory factor analysis of DSM-IV criteria for borderline personality disorder: findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:284–290Google Scholar

7. Shea MT, Stout R, Gunderson J, Morey LC, Grilo CM, McGlashan T, Skodol AE, Dolan-Sewell R, Dyck I, Zanarini MC, Keller MB: Short-term diagnostic stability of schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:2036–2041Google Scholar

8. Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Gunderson JG, Pagano ME, Yen S, Zanarini MC, Shea MT, Skodol AE, Stout RL, Morey LC, McGlashan TH: Two-year stability and change in schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004; 72:767–775Google Scholar

9. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR: The longitudinal course of borderline psychopathology: 6-year prospective follow-up of the phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160:274–283Google Scholar

10. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Reich DB, Silk KR: The McLean Study of Adult Development (MSAD): overview and implications of the first 6 years of prospective follow-up. J Personal Disord 2005; 19:505–523Google Scholar

11. Kagan J, Snidman N: The Long Shadow of Temperament. Cambridge, Mass, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2004Google Scholar

12. McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Ralevski E, Morey LC, Gunderson JG, Skodol AE, Shea MT, Zanarini MC, Bender D, Stout RL, Yen S, Pagano M: Two-year prevalence and stability of individual DSM-IV criteria for schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: toward a hybrid model of axis II disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:883–889Google Scholar

13. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, McGlashan TH, Morey LC, Sanislow CA, Bender DS, Grilo CM, Zanarini MC, Yen S, Pagano ME, Stout RL: Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (CLPS): overview and implications. J Personal Disord 2005; 19:487–504Google Scholar

14. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624–629Google Scholar

15. Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL: The Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines: discriminating BPD from other axis II disorders. J Personal Disord 1989; 3:10–18Google Scholar

16. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL, Gunderson JG: The Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders: interrater and test-retest reliability. Compr Psychiatry 1987; 28:467–480Google Scholar

17. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Vujanovic AA: The interrater and test-retest reliability of the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R). J Personal Disord 2002; 16:270–276Google Scholar

18. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR: Attainment and maintenance of reliability of axis I and II disorders over the course of a longitudinal study. Compr Psychiatry 2001; 42:369–374Google Scholar

19. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Reich DB, Silk KR: Prediction of the 10-year course of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:827–832Google Scholar

20. Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon D, Heard HL: Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:1060–1064Google Scholar

21. Bateman A, Fonagy P: Treatment of borderline personality disorder with psychoanalytically oriented partial hospitalization: an 18-month follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:36–42Google Scholar

22. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR: Mental health service utilization of borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for 6 years. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65:28–36Google Scholar

23. Widiger TA, Trull TS, Clarkin JF, Sanderson C, Costa PT: A description of DSM-IV personality disorders with the five-factor model of personality, in Personality Disorders and the Five-Factor Model of Personality, 2nd ed. Edited by Costa PT, Widiger TA. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2002, pp 89–99Google Scholar