Juvenile Mental Health Histories of Adults With Anxiety Disorders

Abstract

Objective: Information about the psychiatric histories of adults with anxiety disorders was examined to further inform nosology and etiological/ preventive efforts. Method: The authors used data from a prospective longitudinal study of a representative birth cohort (N=1,037) from ages 11 to 32 years, making psychiatric diagnoses according to DSM criteria. For adults with anxiety disorders at 32 years, follow-back analyses ascertained first diagnosis of anxiety and other juvenile disorders. Results: Of adults with each type of anxiety disorder, approximately half had been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder (one-third with an anxiety disorder) by age 15. The juvenile histories of psychiatric problems for adults with different types of anxiety disorders were largely nonspecific, partially reflecting comorbidity at 32 years. Histories of anxiety and depression were most common. There was also specificity. For example, adults with panic disorder did not have histories of juvenile disorders, whereas those with other anxiety disorders did. Adults with posttraumatic stress disorder had histories of conduct disorder, whereas those with other anxiety disorders did not. Adults with specific phobia had histories of juvenile phobias but not other anxiety disorders. Conclusions: Strong comorbidity between different anxiety disorders and lack of specificity in developmental histories of adults with anxiety disorders supports a hierarchical approach to classification, with a broad class of anxiety disorders having individual disorders within it. The early first diagnosis of psychiatric difficulties in individuals with anxiety disorders suggests the need to target research examining the etiology of anxiety disorders and preventions early in life.

Anxiety disorders are among the most common psychiatric difficulties throughout the life course (1 – 4) . In addition to causing human suffering, these disorders entail substantial economic burden (5) . The developmental histories of these disorders are largely neglected in DSM-IV. However, retrospective studies suggest that anxiety disorders begin early in life—the National Comorbidity Study Replication (2) estimates the median age of onset for any anxiety disorder to be 11 years—and these problems often remain untreated for many years. Although researchers have developed sophisticated methodologies to promote accurate recall in retrospective studies, they acknowledge that biases may remain in retrospective reporting, especially when respondents are asked to estimate age at onset of disorders that occurred long ago (2 , 6) . Prospective follow-back studies are, therefore, needed to provide more precise knowledge about the developmental histories of anxiety disorders. This information can be used to inform classification decisions in nosological systems, target research efforts aimed at elucidating the etiology of anxiety disorders, and help target prevention strategies.

Information about developmental histories can inform nosology (7) . Indeed, there is a great deal of debate concerning the best way to categorize anxiety disorders (8) . Anxiety disorders may be split into small homogeneous groups or may be “lumped” into a single phenotype. Hints as to the best way to classify anxiety disorders come from three lines of research. First, factor analyses suggest that although it is appropriate to draw general distinctions between internalizing and externalizing disorders, there are also distinctions between different types of anxiety. Indeed, two independent reports indicate that in addition to a general distinction between internalizing and externalizing disorders, it is possible to draw distinctions within the higher-order internalizing factor. Specifically, there is a second-order factor wherein generalized anxiety disorder is grouped with depression and distinguished from other anxiety disorders (specific and social phobias as well as panic and agoraphobia) (8 – 10) .

Second, studies of shared vulnerability suggest that different anxiety disorders are influenced by the same factors. These studies have also emphasized distinctions between specific disorders. For example, twin research suggests that the genetic etiology of specific phobias may be largely distinct from that of other anxiety disorders (11 , 12) . Further risk factors, such as physical and sexual abuse, are also associated with a variety of anxiety disorders in adulthood. However, research also points to the possibility that there are elevated rates of abuse in patients with specific types of anxiety disorders. Illustrating this point, two studies have suggested that adults with panic disorder relative to other anxiety disorders are particularly likely to have suffered physical and sexual abuse as children (13 , 14) .

Finally, treatment research suggests commonalities between different anxiety disorders. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can be effective in treating a variety of anxiety disorders, including panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (15) . However, SSRIs are not typically used in the treatment of specific phobias, emphasizing the aforementioned distinction between phobias and other anxiety disorders. Similarly, there are commonalities in cognitive behavior therapies for different anxiety disorders (such as the focus on phenomenology in the development of treatments), although there are also clear differences in the content of these therapies for different anxiety disorders (16) .

Another relatively unexplored way of informing nosology is to examine the developmental course of disorders. If different anxiety disorders have different histories, this may suggest that there are important distinctions between these disorders that should be reflected in nosological systems. Conversely, the absence of differences in the developmental histories of anxiety disorders may suggest that it is more appropriate to categorize these disorders together. Follow-forward analyses have informed this issue by showing that anxious behaviors predict a range of subsequent anxiety disorders (17) . However, there is also evidence of specificity in the course of phobias (18) . Follow-back studies are also able to inform this issue, although relevant studies of this nature have not yet been reported.

Information about the developmental histories of disorders is also essential for understanding and effectively preventing later psychopathology. For example, the early onset of anxiety disorders would suggest that research exploring risk factors for the development of anxiety needs to begin early in life, as do preventions. If a certain disorder is particularly likely to precede anxiety disorders, targeting individuals with this disorder may be particularly useful in preventing future occurrence of anxiety disorders.

In an effort to inform classification decisions, target research efforts, and inform preventions, this study investigated the developmental histories of adult anxiety disorders using a follow-back design. We distinguished different anxiety disorders at age 32 years and examined the age at which study members were first diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder and the types of psychiatric disorders occurring developmentally. We tested whether there was 1) strict homotypic continuity , whereby anxiety disorders were preceded by anxiety; 2) broad homotypic continuity , whereby anxiety disorders were more likely to be preceded by internalizing than externalizing disorders; and 3) heterotypic continuity , whereby anxiety disorders were also preceded by externalizing disorders.

This study advances knowledge in two key ways. First, many longitudinal studies have either collapsed all anxiety disorders into one group (19 , 20) or have primarily focused upon a single anxiety disorder (e.g., panic [21] ). In contrast, few studies have examined longitudinal intra-anxiety associations. Here, we compare among anxiety disorders. Second, although studies have examined the lifetime co-occurrence of anxiety disorders (22) , few studies have asked the longitudinal question about similarities and differences in the developmental history of different anxiety disorders. Here, we examine longitudinal associations. Previously, we reported that adults with any anxiety disorder—like those with an affective, substance use, or psychotic disorder—are highly likely to have a childhood psychiatric history (23) . This report elaborates on the type of psychiatric history and examines specificity among the anxiety disorders.

Method

Participants

Participants were members of the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, a longitudinal investigation of the health and behavior of a complete birth cohort. The cohort of 1,037 children (52% male) was constituted at 3 years of age when the investigators enrolled 91% of consecutive births from April 1, 1972, through March 31, 1973, in Dunedin, New Zealand. Cohort families were primarily white and represented the full range of socioeconomic status in the general population of New Zealand’s South Island. At each assessment age, participants (including emigrants living overseas) were brought back to the research unit for a full day of individual data collection. At each assessment, psychiatric interviewing was conducted blind to all study data, as was the assigning of diagnoses. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the participating universities. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained from parents up to age 15 and thereafter from the study members. Follow-up evaluations have been performed at 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 18, 21, 26, and most recently 32 years of age (N=972, 96% of the living cohort members). In this article, we report all available diagnostic data gathered at all ages from 11 to 32 years for the 963 individuals who received a psychiatric interview at 32 years.

Psychiatric Diagnoses

Mental health was assessed in private standardized interviews with the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children for the younger ages (11–15 years) and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for the older ages (18–32 years), with a reporting period of 12 months at each age. Diagnoses were assigned according to the criteria of DSM-III at ages 11, 13 and 15; DSM-III-R at ages 18 and 21; and DSM-IV at ages 26 and 32. Procedures, reliability, validity, prevalence, and evidence of impairment for diagnoses in the cohort are reported elsewhere (1 , 24 – 27) .

The seven anxiety disorders diagnosed at 32 years were generalized anxiety disorder, OCD, PTSD, panic disorder, agoraphobia, specific phobia, and social phobia. Psychiatric diagnoses from assessments before 32 years of age are presented in diagnostic families. Between 18–26 years these included 1) anxiety disorders, 2) major depressive episode, 3) substance use disorders (alcohol dependence, marijuana dependence, and other drug dependence), and 4) conduct disorder (at 18 years only). Between 11–15 years, diagnoses included 1) anxiety disorders (overanxious disorder, separation anxiety, phobias), 2) depressive disorders, 3) conduct disorder (including oppositional defiant disorder at 11 and 13 years), and 4) attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Self-reported delusional beliefs and hallucinatory experiences were also examined at 11 years (28 , 29) .

Statistical Analyses

Prevalence rates for psychiatric disorders and their developmental diagnostic histories are reported, with sex differences in morbidity presented for each disorder (sex ratios are set against 1 for male respondents). Concurrent associations between disorders at 32 years are demonstrated by providing the percentage of cases with one anxiety disorder that have also been identified with another anxiety disorder. Follow-back longitudinal analyses were conducted to determine what percentage of anxiety cases at age 32 had a developmental history characterized by 1) any disorder and 2) an anxiety disorder. Significance testing was carried out using chi-square analyses.

Results

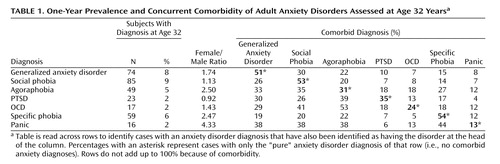

Of the seven anxiety disorders at age 32, the 1-year prevalence rates ranged from 2% (PTSD, OCD, and panic) to 9% (social phobia) ( Table 1 ). More women than men experienced most anxiety disorders. Table 1 also shows concurrent comorbidity between the various anxiety disorders, underscoring its extent. For example, 30% of those with generalized anxiety disorder met criteria for social phobia, and only 13% of those suffering panic disorder did not meet criteria for another anxiety disorder.

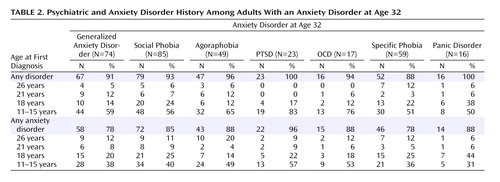

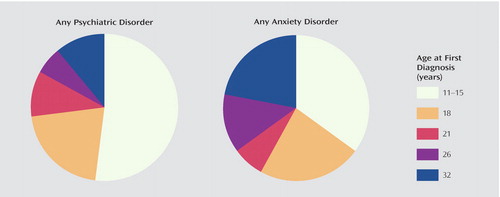

Table 2 presents the mental health history of study members who met diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder at 32 years. Virtually all persons who met criteria at age 32 years for a DSM-IV anxiety disorder in the preceding 12 months had met criteria for a psychiatric disorder at an earlier age (range for specific diagnoses: 88%–100%), and of these at least 50% had met diagnostic criteria for a psychiatric disorder by age 15 (see also Figure 1 ).

Table 2 also presents the anxiety disorder histories of study members who met diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder at age 32. Over 75% of persons diagnosed at age 32 with any DSM-IV anxiety disorder in the preceding 12 months had met criteria for an anxiety disorder at an earlier age (range for specific diagnoses: 78%–96%), and over one-third had an anxiety disorder before age 15 (see also Figure 1 ).

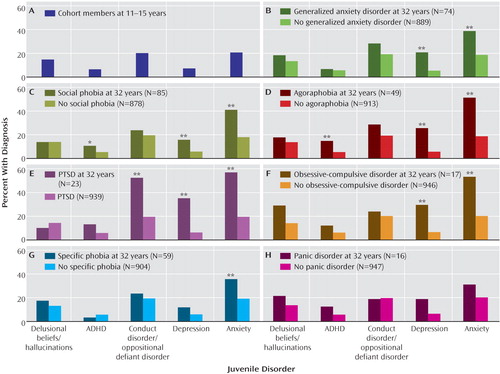

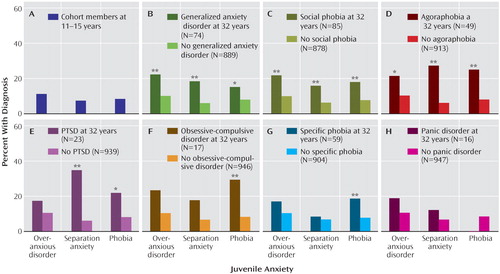

Follow-back analyses focused on prior diagnoses when participants were 11–15 years of age, since this period clearly reflects a juvenile phase in development and represents a propitious opportunity for early intervention. The prevalence of childhood disorders in the overall sample at 11 to 15 years of age is presented in Figure 2 (panel A).

*p<0.05. **p<0.01.

Figure 2 also shows follow-back analyses for each of the seven different age 32 anxiety disorders (panels B–H). Three findings are noteworthy. First, all adult cases of anxiety had an excess of juvenile anxiety disorders. This association reached significance for each anxiety disorder, with the exception of panic disorder. Second, adult cases of anxiety, regardless of the specific disorder, were also more likely to have experienced juvenile depression relative to those without adult anxiety. This association was significant for each type of anxiety disorder except for specific phobias and panic disorder. Third, adults with certain anxiety disorders (social phobia, agoraphobia, and PTSD) were significantly more likely to have experienced externalizing spectrum disorders than those without these disorders. Most strikingly, adults with PTSD were likely to have met diagnostic criteria for conduct or oppositional defiant disorder.

Figure 3 looks more specifically at the kinds of juvenile anxiety disorders that characterized adults who met diagnostic criteria for each of the seven anxiety disorders. Three findings are particularly salient. First, there was very little specificity in the association between adult and juvenile anxiety disorders. For the most part, regardless of their specific form, adult anxiety cases were more likely than comparison adults to have been diagnosed with overanxious disorder, separation anxiety, and phobias. Second, adult cases of specific phobia stand out for having a significant developmental history of juvenile phobias, but not of overanxious disorder or separation anxiety. Third, adult cases of panic disorder stand out for having no significant developmental history of anxiety disorder.

*p<0.05. **p<0.01.

Discussion

This study examined the developmental histories of adults with anxiety disorders using a prospective follow-back design in order to inform nosology, to target research efforts aimed at understanding etiological mechanisms, and to inform preventions. Five main results emerged. First, the developmental stage at which study members were first diagnosed with a disorder was similar for adults with different types of anxiety disorders. Adults with anxiety disorders typically experienced a psychiatric disorder—and more specifically an anxiety disorder—early in life, and there were few “new” cases emerging later in life. Second, there was evidence for strict homotypic continuity , and it was found that adults with all anxiety disorders (except panic) had experienced significantly more anxiety disorders as juveniles and that juvenile anxiety disorders were the most common history across all adult anxiety diagnoses. Third, there was also evidence for broad homotypic continuity , whereby adults with most types of anxiety also had a juvenile history of depression. Fourth, there was little evidence for heterotypic continuity , since adults with anxiety disorders did not typically have a significant history of externalizing disorders or psychotic symptoms. Finally, there was some evidence of specificity. Three trends are particularly noteworthy: adults with PTSD, as opposed to other anxiety disorders, had juvenile histories of conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder; adults with OCD, but not other anxiety disorders, tended to have childhood self-reports of delusional beliefs and hallucinatory experiences (although not statistically significant, the odds ratio was 2.49); and there was some evidence of specificity within phobias, with specific phobias in adulthood preceded by juvenile phobias but not other anxiety disorders. Although the significance of differences between developmental histories of adults with different anxiety disorders was not examined because of anxiety disorder comorbidity at 32 years, these associations appeared despite the overlap between anxiety disorders in adulthood and chime well with previous research highlighting these associations (18 , 30 , 31) .

Implications

The five main results of this study have implications for nosology, etiology, and prevention. Four of the five main results suggest that a general approach to the classification of anxiety disorders may be warranted. Indeed, there were similarities in the developmental histories of the different anxiety disorders in terms of the juvenile stage at which sufferers were first diagnosed with a disorder and the types of disorders occurring previously, generally internalizing disorders. Similar developmental histories are not unexpected, given the comorbidity of different anxiety disorders at 32 years. It should also be acknowledged that some of the more specific findings, including the finding that specific phobias in adulthood were associated with juvenile phobias but not other disorders, suggest that certain disorders may warrant classification independent of other anxiety disorders. Overall, our findings fit well with a proposed hierarchical approach to classification, with a broad class of internalizing disorders having individual anxiety disorders within it (8) .

The history of disorders in adults with anxiety disorders also suggests that research aimed at understanding the etiology of anxiety needs to begin early in life, and before the youngest age assessed here. This finding points to the need to improve methods of assessing anxiety in young children.

In line with previous suggestions (2 , 23) , our findings also suggest that prevention efforts should begin early in life. Similar conclusions have been drawn concerning other adult disorders, including depression, eating, and substance use disorders (23) . As for whom should be targeted early in life, the results of this study indicate that those who experience depression or anxiety (particularly phobias, which preceded six of the seven anxiety disorders) as juveniles may be particularly good candidates for prevention. Given the longitudinal overlap between different types of anxiety disorders, developing general techniques to help individuals deal with various anxiety symptoms may be particularly beneficial. Once administered, preventions and interventions can have long-term benefits (32) . Although the practical difficulties of attempting to prevent the development of anxiety in the general population are formidable, educating those who have regular contact with children (e.g., teachers) to identify and help particularly anxious children could prove fruitful, as could addressing anxiety in children visiting general practitioners for routine check-ups. Clinicians who treat adults with anxiety disorder may find their case conceptualizations benefit from information about their client’s developmental mental health histories. Indeed, knowing that the dysfunctional cognitions and behaviors that are being addressed in cognitive behavior therapy sessions are likely to have emerged early in life may help the clinician to trace and address the origins of such thoughts and behaviors.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of this study, including the use of an entire birth cohort, prospective measures, and the low attrition rate, there were a number of limitations. First, juvenile data were recorded in a way that did not distinguish social and specific phobias, although given the prevalence rates reported in other studies (18) it is likely there were more specific phobias than social phobias in this cohort. This limitation is particularly noteworthy because previous research has demonstrated specificity within phobias (adolescent simple phobia predicted simple phobia in adulthood whereas social phobia in adolescence predicted later social phobia [18] ). Second, the standardized diagnostic interview we used to examine juvenile disorders may have difficulties in identifying and distinguishing certain anxiety disorders (33) . Third, psychiatric disorders were first examined when the study members were 11 years old. However, it is possible that some cases of anxiety disorders began before this age (2 , 34) . Indeed, we may have missed important information about a number of disorders such as separation anxiety disorder, which typically occurs early in life and has been linked to a range of anxiety disorders later in life (35) . This limitation, together with 1-year gaps between juvenile assessments, means that early difficulties experienced by adults with anxiety disorders may be undercounted in this report. Fourth, although we waited until age 32 years to carry out these analyses (since this is past the peak age of anxiety onset), new cases of anxiety will appear later in life (2) , so the associations reported here may not apply to older adults. The fifth limitation is that there were small subject numbers for certain groups of anxiety disorders at 32 years, with associated lack of power. Care should be taken in drawing conclusions from null results, such as the finding that panic disorder (which was only experienced by 16 study members at 32 years) was not associated with any juvenile disorder. While this finding is consistent with the age at onset of panic disorder reported in the National Comorbidity Study Replication (median 25 years with 75% having onset later than 16 years [2] ), it may also reflect in part the DSM categorical approach, and it is possible that there would have been continuity had symptom scales been examined or if the DSM-IV disorder threshold were lower. Sixth, we aimed to add information beyond prior studies (which studied only one disorder, or lumped all anxiety disorders into one group) by making comparisons among the different adult anxiety disorders. However, because of the high levels of comorbidity we observed among the adult anxiety disorders, our study group size did not allow us to test for the statistical significance of the comparisons between each adult anxiety disorder and healthy comparison subjects while controlling for all other adult anxiety disorders. Nevertheless, we presented the findings for each disorder separately to stimulate hypotheses for future studies with larger samples. Seventh, since this report focuses upon a single cohort, the results of this study may not apply to other birth cohorts. This is particularly salient as cohort differences have been suggested for certain anxiety disorders (2) .

Given similarities in the developmental histories of adults with different types of anxiety disorders, it may be wise to categorize these disorders together, while at the same time acknowledging differences between disorders. Our results also document that anxiety, as seen with other psychiatric disorders, first begins early in life. The diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of anxiety disorders may benefit from including this type of information in future editions of DSM.

1. Anderson JC, Williams S, McGee R, Silva A: DSM-III disorders in preadolescent children. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:69–80Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Walters EE: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:593–602Google Scholar

3. Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Andrews JA: Adolescent psychopathology, I: prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM-III-R disorders in high school children. J Abnorm Psychol 1993; 102:133–144Google Scholar

4. Wittchen HU, Essau CA, Vonzerssen D, Krieg JC, Zaudig M: Lifetime and 6-month prevalence of mental disorders in the Munich follow-up-study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1992; 241:247–258Google Scholar

5. Rice DP, Miller LS: Health economics and cost implications of anxiety and other mental disorders in the United States. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 173:4–9Google Scholar

6. Simon GE, Vonkorff M: Recall of psychiatric history in cross-sectional surveys: implications for epidemiologic research. Epidemiol Rev 1995; 17:221–227Google Scholar

7. Widiger TA, Clark LA: Toward DSM-V and the classification of psychopathology. Psychol Bull 2000; 126:946–963Google Scholar

8. Watson D: Rethinking the mood and anxiety disorders: a quantitative hierarchical model for DSM-V. J Abnorm Psychol 2005; 114:522–536Google Scholar

9. Krueger RF: The structure of common mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:921–926Google Scholar

10. Vollebergh WAM, Iedema J, Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Smit F, Ormel J: The structure and stability of common mental disorders: The Nemesis Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:597–603Google Scholar

11. Hettema JM, Prescott CA, Myers JM, Neale MC, Kendler KS: The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for anxiety disorders in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:182–189Google Scholar

12. Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC: The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:929–937Google Scholar

13. Safren SA, Gershuny BS, Marzol P, Otto MW, Pollack MH: History of childhood abuse in panic disorder, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002; 190:453–456Google Scholar

14. Stein MB, Walker JR, Anderson G, Hazen AL, Ross CA, Eldridge G, Forde DR: Childhood physical and sexual abuse in patients with anxiety disorders and in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:275–277Google Scholar

15. Morilak DA, Frazer A: Antidepressants and brain monoaminergic systems: a dimensional approach to understanding their behavioural effects in depression and anxiety disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharm 2004; 7:193–218Google Scholar

16. Clark DM: Developing new treatments: on the interplay between theories, experimental science and clinical innovation. Behav Res Ther 2004; 42:1089–1104Google Scholar

17. Goodwin RD, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ: Early anxious/withdrawn behaviours predict later internalising disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004; 45:874–883Google Scholar

18. Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma YJ: The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:56–64Google Scholar

19. Hofstra MB, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC: Child and adolescent problems predict DSM-IV disorders in adulthood: A 14-year follow-up of a Dutch epidemiological sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:182–189Google Scholar

20. Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM: Life course outcomes of young people with anxiety disorders in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001; 40:1086–1093Google Scholar

21. Goodwin RD, Lieb R, Hoefler M, Pfister H, Bittner A, Beesdo K, Wittchen HU: Panic attack as a risk factor for severe psychopathology. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:2207–2214Google Scholar

22. Lewinsohn PM, Zinbarg R, Seeley JR, Lewinsohn M, Sack WH: Lifetime comorbidity among anxiety disorders and between anxiety disorders and other mental disorders in adolescents. J Anxiety Disord 1997; 11:377–394Google Scholar

23. Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R: Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:709–717Google Scholar

24. Frost LA, Moffitt TE, McGee R: Neuropsychological correlates of psychopathology in an unselected cohort of young adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol 1989; 98:307–313Google Scholar

25. McGee R, Feehan M, Williams S, Partridge F, Silva PA, Kelly J: DSM-III disorders in a large sample of adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1990; 29:611–619Google Scholar

26. Feehan M, McGee R, Raja SN, Williams SM: DSM-III-R disorders in New Zealand 18-year-olds. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1994; 28:87–99Google Scholar

27. Newman DL, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Magdol L, Silva PA, Stanton WR: Psychiatric disorder in a birth cohort of young adults: prevalence, comorbidity, clinical significance, and new case incidence from ages 11 to 21. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996; 64:552–562Google Scholar

28. Cannon M, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Taylor A, Murray RM, Poulton R: Evidence for early-childhood, pan-developmental impairment specific to schizophreniform disorder: results from a longitudinal birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:449–456Google Scholar

29. Poulton R, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Cannon M, Murray R, Harrington H: Children’s self-reported psychotic symptoms and adult schizophreniform disorder: a 15-year longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:1053–1058Google Scholar

30. Koenen KC, Fu QJ, Lyons MJ, Toomey R, Goldberg J, Eisen SA, True W, Tsuang M: Juvenile conduct disorder as a risk factor for trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress 2005; 18:23–32Google Scholar

31. Correll CU, Lencz T, Smith CW, Auther AM, Nakayama EY, Hovey L, Olsen R, Shah M, Foley C, Cornblatt BA: Prospective study of adolescents with subsyndromal psychosis: characteristics and outcome. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2005; 15:418–433Google Scholar

32. Kendall PC, Safford S, Flannery-Schroeder E, Webb A: Child anxiety treatment: outcomes in adolescence and impact on substance use and depression at 7.4-year follow-up. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004; 72:276–287Google Scholar

33. Horwath E, Lish JD, Johnson J, Hornig CD, Weissman MM: Agoraphobia without panic: clinical reappraisal of an epidemiologic finding. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1496–1501Google Scholar

34. Costello EJ, Egger H, Angold A: 10-year research update review: the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders, I: methods and public health burden. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44:972–986Google Scholar

35. Aschenbrand SG, Kendall PC, Webb A, Safford SM, Flannery-Schroeder E: Is childhood separation anxiety disorder a predictor of adult panic disorder and agoraphobia? A seven-year longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:1478–1485Google Scholar