Physiologic Reactivity Despite Emotional Resilience Several Years After Direct Exposure to Terrorism

Abstract

Objective: Six and a half to 7 years after the 1995 terrorist bombing in Oklahoma City, the authors assessed autonomic reactivity to trauma reminders and psychiatric symptoms in adults who had some degree of direct exposure to the blast. Method: Sixty survivors who were listed in a state health department registry of persons exposed to the bombing and 60 age- and gender-matched members of the Oklahoma City metropolitan area community were assessed for symptoms of PTSD and depression and for axis I diagnoses. Heart rate and systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial blood pressures were measured before, during, and after bombing-related interviews. The two groups were compared on both psychometric and physiologic assessments. Results: Posttraumatic stress but not depressive symptoms were significantly more prevalent in the survivor group than in the comparison group, although symptoms were below levels considered clinically relevant. Despite apparent emotional resilience or recovery, blast survivors had significantly greater autonomic reactivity to trauma reminders on all measures than comparison subjects. Conclusions: The results suggest that physiologic assessment may capture long-term effects of terrorism that are not identified by psychometric instruments. The consequences of autonomic reactivity despite emotional resilience years after experiencing trauma are unknown but theoretically could range from facilitating a protective vigilance toward future disasters to more maladaptive avoidance behaviors, somatic symptoms, or medical problems.

Terrorist attacks are associated with high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (1 – 5) , and studies have explored various factors linked with the risk of terrorism-related symptoms and diagnosis of PTSD (6 – 10) . Physiologic reactivity to trauma cues has been documented as one of the biological abnormalities associated with PTSD (11 – 20) . However, studies that explore physiologic reactivity in victims of terrorism are lacking, in part because of the difficulty of gaining access to sufficient numbers of survivors who were exposed to the same or similar events and of making physiologic assessments after similar time intervals since the event. Because we have maintained contact with a number of survivors of the 1995 terrorist bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City who have been willing to contribute to research, we were able to conduct a study of their psychiatric symptoms and autonomic reactivity to reminders of their experience several years later.

We examined 60 directly exposed survivors of the bombing and 60 community comparison subjects approximately 6½ to 7 years after the event. We recorded demographic characteristics, assessed psychiatric symptoms and mental health sequelae of the bombing, and measured physiologic reactivity before, during, and after a semistructured interview eliciting memories of the event. Three hypotheses motivated this study. One was that directly exposed survivors would have clinically significant elevations of bombing-related symptoms of PTSD and depression and would have higher numbers of these symptoms than comparison subjects. Another was that autonomic reactivity to reminders of the bombing would be greater among survivors than among comparison subjects. Our third hypothesis was that measures of autonomic reactivity would correlate with measures of posttraumatic stress symptoms.

Method

Participants

Our study subjects were listed in a state health department registry of persons who had varying degrees of direct exposure to the 1995 Oklahoma City bomb blast. All of these survivors had been in the original group assessed by North and colleagues 6 months and again 18 months (7 , 21) after the bombing, and nearly all were recruited for this study from a group of 113 survivors who were participating in a study assessing survivors 6½ to 7 years after the bombing. Potential participants were eligible for the physiologic assessment if they were not taking psychotropic or cardiovascular medications and if they had no untreated or unstable medical illnesses that would affect the physiologic measures in the assessment. We originally planned to begin contacting potential subjects for this study in September 2001, but after the terrorist attacks in New York City and Washington, D.C., on September 11, we decided to delay starting until late October to avoid potentially contaminating results with reactions to the more recent events.

A total of 78 survivors met criteria for the study and consented to participate; of these, only 60 completed all the psychometric instruments as well as the physiologic assessment and were included in the final data analysis. Participants who completed all assessments did not differ significantly in demographic characteristics or in physiologic reactivity from those who did not.

We also recruited 60 age- and gender-matched comparison subjects who resided in the Oklahoma City metropolitan area at the time of the bombing and who were not in the immediate vicinity of the blast, did not have friends or relatives killed in the bombing, and were not rescue or recovery workers. As with the survivors participating in the study, eligibility criteria for comparison subjects included being free of psychotropic or cardiovascular medications and any untreated or unstable medical illnesses. All participants were asked to avoid caffeine and to refrain from smoking and taking any nonessential medications for at least 3 hours before the assessment.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and requirements of the institutional review boards of both the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and the Washington University School of Medicine. All participants were paid a nominal fee for participating in the study.

Physiologic Assessment

To avoid any confounding effect the psychometric assessment battery might have on autonomic responses, we performed the physiologic assessment first. The physiologic assessment entailed measuring heart rate and systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial blood pressures, using procedures that have been described in the literature (11 , 12 , 17 – 19) . Three sets of measurements lasting 4 minutes each were made: a pretest phase, with the participant at rest; a testing phase, during which a semistructured interview about the bombing was conducted; and a posttest phase, with the participant at rest after the interview was completed. Each participant was debriefed by a mental health professional afterward.

Psychometric Instruments

The DSM-IV version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (22) was administered by a trained research assistant to assess for the presence of any axis I conditions during the preceding 30 days. The DIS Disaster Supplement Interview and Questionnaire (23) , which was adapted from the DIS Disaster Supplement (24) , was used to obtain information about demographic characteristics, disaster exposure, level of functioning, and health and mental health.

PTSD symptoms were measured with items from the Impact of Event Scale–Revised (IES-R) (25 , 26) , a 22-item self-report scale quantifying PTSD symptoms in the three symptom clusters for the preceding 7 days, with reference to the Oklahoma City bombing. To be consistent with methods we used in previous studies (7 , 27 , 28) , we scored each item on a 4-point scale (1=not at all, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, and 4=often; possible scores thus range from 22 to 88), rather than using Weiss and Marmar’s (26) 5-point scale.

Depressive symptoms were measured with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (29) , a self-report inventory of 21 items, each scored from 0 to 3, with 3 representing the greatest severity (possible scores ranging from 0 to 63). Scores ranging from 0 to 9 are considered not clinically significant; scores from 10 to 17 suggest mild depression, and 18 to 24, moderate depression; a score of 25 or higher indicates severe depressive symptoms.

Data Analysis

Paired t tests were used to compare the two groups’ mean total scores on the modified IES-R and the BDI. For each physiologic variable—heart rate and systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial blood pressures—means and standard deviations were calculated for both groups for the pretest, testing, and posttest phases. A two-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) (two groups by three testing phases for matched subjects and repeated measures on testing phase) was used for a global analysis for each variable separately. Each ANOVA was followed by a set of planned contrasts examining the within-group differences between pretest and test means and between pretest and posttest means on physiologic variables and comparing these differences between the two groups.

We computed physiologic reactivity scores by subtracting pretest from testing phase values on the physiologic variables for the two groups and physiologic reactivity persistence scores by subtracting pretest from posttest values. Independent-sample t tests were used to compare groups. Spearman correlations were used to examine the association between reactivity scores and measures of PTSD symptoms derived from the modified IES-R for the two groups. We also used t tests to compare physiologic reactivity scores for the 60 survivors for whom complete psychometric data were available with scores for the 18 survivors whose psychometric data were incomplete, and to compare reactivity scores for survivors who met PTSD criteria and those who did not.

Results

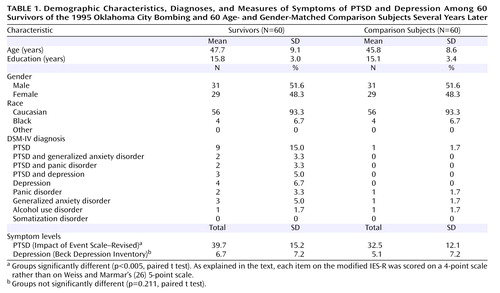

Table 1 summarizes demographic characteristics and DSM-IV diagnoses as assessed by the DIS for the 60 survivors and 60 age- and gender-matched community comparison subjects. The groups were strikingly comparable in mean years of education, although they were not matched on this variable. According to DIS results, nine of the survivors and one comparison subject had current PTSD.

Although eligibility for the study included not taking psychotropic medications or medications that would affect autonomic measures, we learned later that three participants in the survivor group—two with and one without PTSD—were taking medications that have CNS effects. One of those with PTSD was taking temazepam, and the other was taking tramadol, gabapentin, tizanidine, citalopram, hydroxyzine, and diphenhydramine. The survivor without PTSD was taking fluoxetine. Excluding these three participants from the analyses did not result in any differences in the group’s physiologic reactivity scores.

Overall, the survivors reported intense exposure to the bombing, with marked rates of injury or illnesses (N=47, 83.9%), need for medical care (N=42, 76.8%), and hospitalizations (N=15, 26.8%) due to the bombing. Most reported that they had recovered (N=31, 66%) or partly recovered (N=14, 29.8%) from harm they attributed to the bombing.

Psychometric Assessment

Although survivors reported a significantly higher number of posttraumatic stress symptoms than comparison subjects ( Table 1 ), symptoms did not reach clinically relevant levels and were below the “rarely” category on the modified IES-R for both groups. The number of depressive symptoms did not differ significantly between survivors and comparison subjects, and both groups had total BDI scores below 10, which falls within the normal range.

Physiologic Measures

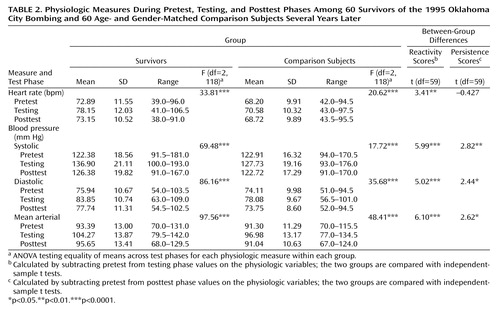

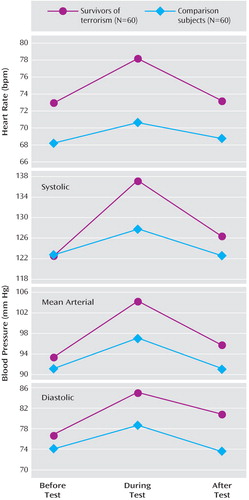

Table 2 summarizes the physiologic assessment data for the two groups, and Figure 1 illustrates heart rate and blood pressure reactivity for the two groups during the three phases. At baseline, the groups did not differ significantly in the various blood pressure measures, but the survivor group had a significantly higher mean resting heart rate than the comparison group (t=2.745, p=0.007). For both groups, the ANOVA’s testing equality of means across the three test phases showed significant group-by-test-phase interactions (in pretest to posttest change scores) for all four variables.

Both groups had significant within-group increases in all autonomic measures between the pretest and testing phases, although survivors had significantly larger increases than the comparison group. Survivors also maintained significant within-group increases from pretest levels in the posttest phase in all measures except heart rate, whereas the comparison group did not maintain significant increases on any measure.

Comparisons of physiologic reactivity scores for the nine survivors with PTSD and the 51 without PTSD showed no significant differences in any autonomic reactivity variable. Spearman correlations showed no significant associations in either group between IES-R total score and reactivity scores for any physiologic measure.

Vignette

One direct survivor, Mr. A, a 57-year-old married man, was in his office in the Murrah Federal Building when the bomb exploded. He was thrown against the wall and suffered minor injuries in the explosion. His immediate response was fear and a desire to escape the building; on the way out, he helped a seriously injured woman get through thick smoke to rescue workers. Mr. A suffered acute stress symptoms for 2 weeks. He coped by going to church three times a week and by developing his “own personal philosophy” to overcome his anger and sadness and forgive Timothy McVeigh, who was later convicted and executed for the bombing.

Mr. A said that the event did not bother him currently, which is consistent with his low total score of 22 on the modified IES-R and his not having an axis I diagnosis. However, he demonstrated robust blood pressure reactivity during the structured interview about the bombing; his systolic pressure increased from a pretest value of 120 mm Hg to 138 mm Hg during the test, and it remained elevated at 133 in the posttest phase. His diastolic pressure increased from 85.5 at pretest to 95 during the testing phase and remained elevated at 94 in the posttest phase.

Discussion

Although the survivor group had high rates of injury and significantly more posttraumatic stress symptoms than the community comparison group, survivors nonetheless had low levels of PTSD symptoms and a low rate of PTSD diagnoses, which suggests that they either were resilient or had experienced emotional healing over time. Alternatively, it is possible that the physiologic assessment procedure introduced selection bias; potential participants who had more severe psychological sequelae may have elected not to enroll in the study, and those taking psychotropic medications would have been excluded by the eligibility criteria. Despite their apparent emotional health, the survivor group had a greater physiologic reactivity than a community comparison group to reminders of the bombing, which is consistent with physiologic assessment studies of chronic PTSD (11 cvb, 14 , 30) . Our survivor group’s biological sensitivity to the reminders was independent of PTSD diagnosis and symptom levels, a finding that parallels Rahe and colleagues’ (31) findings of low PTSD symptom levels despite neuroendocrine stress response patterns among freed hostages. These results suggest that the residue of trauma exposure may persist less in narrative ratings of emotional effects than in physiologic differences that may be independent of the pathophysiology of PTSD. It is also possible that the disconnection between emotional symptoms and biological sensitivity in survivors of bombings is an aspect of either resilience or healing. Charney (32) has described the adaptive physiologic response to severe stress as promoting survival acutely, but he noted that over time this response must be balanced by homeostatic response to prevent harmful long-term effects on psychological and physiologic functioning. In our bombing survivors, recovery might involve developing behaviors that could facilitate taking effective action to survive in a future disaster. Such findings raise additional questions about what responses to trauma are normative and adaptive, and what responses represent psychopathology (such as PTSD).

Our study, despite its limitations, is the largest investigation we know of that measured the lasting impact of a single terrorist act on directly exposed survivors through psychophysiologic assessment. Our survivor group showed unexpected emotional hardiness despite strong physiologic reactivity to reminders of the experience. Policy makers planning for long-term mental health care and medical care of terrorism survivors would do well to consider that enduring disturbances in the biological steady state could contribute to avoidance behaviors, constriction of lifestyle, somatic complaints, health care seeking, or possibly earlier onset of medical or cardiovascular illness in those who are already at risk. Oklahoma City community members, including direct survivors, have responded along a continuum from emotional health to severe and lasting psychopathology and disability. Some report feeling a sense of closure with the perpetrators executed or incarcerated, and some do not. Subsequent terrorist acts across the globe, although different in many respects from the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, often rekindle memories and associated complex responses of fear, anger, sadness, altruism, and forgiveness in those whose lives were affected.

1. Committee on Responding to the Psychological Consequences of Terrorism: Preparing for the Psychological Consequences of Terrorism: A Public Health Strategy. Edited by Butler AS, Panzer AM, Goldfrank LR. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2003, p 1Google Scholar

2. Gidron Y: Posttraumatic stress disorder after terrorist attacks: a review. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002; 190:118–121Google Scholar

3. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:1048–1060Google Scholar

4. Shalev AY, Freedman S: PTSD following terrorist attacks: a prospective evaluation. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1188–1191Google Scholar

5. Verger P, Dab W, Lamping DL, Loze J-I, Deschaseaux-Voinet C, Abenhaim L, Rouillon F: The psychological impact of terrorism: an epidemiologic study of posttraumatic stress disorder and associated factors in victims of the 1995–1996 bombings in France. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:1384–1389Google Scholar

6. Abenhaim L, Dab W, Salmi LR: Study of civilian victims of terrorist attacks (France 1982–1987). J Clin Epidemiol 1992; 45:103–109Google Scholar

7. North CS, Nixon SJ, Shariat S, Mallonee S, McMillen JC, Spitznagel EL, Smith EM: Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. JAMA 1999; 282:755–762Google Scholar

8. Tucker P, Pfefferbaum B, Nixon SJ, Dickson W: Predictors of post-traumatic stress symptoms in Oklahoma City: exposure, social support, peri-traumatic responses. J Behav Health Serv Res 2000; 27:406–416Google Scholar

9. Wilson FC, Poole AD, Trew K: Psychological distress in police officers following critical incidents. Irish J Psychol 1997; 18:321–340Google Scholar

10. Shalev AY: Posttraumatic stress disorder among injured survivors of a terrorist attack: predictive value of early intrusion and avoidance symptoms. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992; 180:505–509Google Scholar

11. Pitman RK, Orr SP, Forgue DF, de Jong JB, Claiborn JB: Psychophysiological assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder imagery in Vietnam combat veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:970–975Google Scholar

12. Pitman RK, Orr SP, Steketee GS: Psychophysiological investigations of posttraumatic stress disorder imagery. Psychopharmacol Bull 1989; 25:426–431Google Scholar

13. McFall ME, Murburg MM, Ko GN, Veith RC: Autonomic responses to stress in Vietnam combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1990; 27:1165–1175Google Scholar

14. Orr SP, Claiborn JM, Altman B, Forgue DF, de Jong JB, Pitman RK: Psychometric profile of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxious and healthy Vietnam veterans: correlations with psychophysiological responses. J Consult Clin Psychol 1990; 58:329–335Google Scholar

15. Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Taylor AE: The psychophysiology of motor vehicle accident related posttraumatic stress disorder. Biofeedback Self Regul 1993; 16:449–458Google Scholar

16. Rothbaum BO, Kozak MJ, Foa EB, Whitaker DJ: Posttraumatic stress disorder in rape victims: autonomic habituation to auditory stimuli. J Traum Stress 2001; 14:283–293Google Scholar

17. Shalev AY, Orr SP, Pitman RK: Psychophysiologic assessment of traumatic imagery in Israeli civilian patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:620–624Google Scholar

18. Tucker P, Smith KL, Marx B, Jones D, Miranda R, Lensgraf J: Fluvoxamine reduces physiologic reactivity to trauma scripts in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 20:367–372Google Scholar

19. Shalev AY, Peri T, Gelpin E, Orr SP, Pitman RK: Psychophysiologic assessment of mental imagery of stressful events in Israeli civilian posttraumatic stress disorder patients. Comp Psychiatry 1997; 38:269–273Google Scholar

20. Shalev AY, Sahar T, Freedman S, Peri T, Glick N, Brandes D, Orr SP, Pitman RK: A prospective study of heart rate response following trauma and the subsequent development of posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:553–559Google Scholar

21. North CS: The course of posttraumatic stress disorder after the Oklahoma City bombing. Military Med 2001; 166(12 suppl):51–52Google Scholar

22. Robins LN, Cottler LB, Compton WM, Bucholz K, North CS, Roarke K: Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version 4.2. St Louis, MO, Washington University, Department of Psychiatry, 1998Google Scholar

23. North CS, Pfefferbaum B: The Diagnostic Interview Schedule/Disaster Supplement Questionnaire. St Louis, MO, Washington University, 2002Google Scholar

24. Robins LN, Smith EM: The Diagnostic Interview Schedule/Disaster Supplement. St Louis, MO, Washington University, 1992Google Scholar

25. Horowitz, M, Wilner N, Alvarez W: Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 1979; 41:209–128Google Scholar

26. Weiss DS, Marmar CR: The Impact of Event Scale–Revised, in Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD. Edited by Wilson JP, Keane TM. New York, Guilford, 1997, pp 399–411Google Scholar

27. Pfefferbaum B, Nixon SJ, Krug RS, Tivis RD, Moore VL, Brown JM, Pynoos RS, Foy D, Gurwitch RH: Clinical needs assessment of middle and high school students following the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1069–1074Google Scholar

28. Pfefferbaum B, Pfefferbaum, RL, Gurwitch RH, Doughty DE, Pynoos RS, Foy DW, Brandt EN Jr, Reddy C: Teachers’ psychological reactions 7 weeks after the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2004; 74:263–271Google Scholar

29. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4:561–571Google Scholar

30. Orr SP, Lasko NB, Metzger LJ, Berry NJ, Ahern CE, Pitman RK: Psychophysiologic assessment of women with posttraumatic stress disorder resulting from childhood sexual abuse. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998; 66:906–913Google Scholar

31. Rahe RH, Karson S, Howard NS Jr, Rubin RT, Poland RE: Psychological and physiological assessments on American hostages freed from captivity in Iran. Psychosom Med 1990; 52:1–16Google Scholar

32. Charney DS: Psychobiological mechanisms of resilience and vulnerability: implications for successful adaptation to extreme stress. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161:195–216Google Scholar