Olanzapine Versus Placebo in the Treatment of Adolescents With Bipolar Mania

Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of olanzapine for the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar disorder in adolescents. Method: A 3-week multicenter, parallel, double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial was conducted at 24 sites in the United States and two sites in Puerto Rico. The participants were outpatient and inpatient male and female adolescents 13–17 years of age with an acute manic or mixed episode. Subjects received either olanzapine (2.5–20 mg/day [N=107]) or placebo (N=54). The mean change from baseline to endpoint in the Young Mania Rating Scale total score was the primary outcome measure. Results: The mean baseline-to-endpoint change in the Young Mania Rating Scale total score was significantly greater for patients receiving olanzapine relative to patients receiving placebo, and a greater proportion of olanzapine-treated patients met response and remission criteria (44.8% versus 18.5% and 35.2% versus 11.1%, respectively). The mean baseline-to-endpoint weight change was significantly greater for patients receiving olanzapine relative to patients receiving placebo (3.7 kg versus 0.3 kg), and the incidence of treatment-emergent weight gain ≥7% of baseline was higher for olanzapine-treated patients (41.9% versus 1.9%). The mean baseline-to-endpoint changes in prolactin, fasting glucose, fasting total cholesterol, uric acid, and the hepatic enzymes aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase were significantly greater in patients treated with olanzapine relative to patients receiving placebo. Conclusions: Olanzapine was effective in the treatment of bipolar mania in adolescent patients. Patients treated with olanzapine, however, had significantly greater weight gain and increases in the levels of hepatic enzymes, prolactin, fasting glucose, fasting total cholesterol, and uric acid.

Bipolar disorder is a devastating condition with an estimated prevalence of 0.1%–2% among adolescents (1 – 3) . The prevalence of bipolar disorder in adults has been reported to be as high as 3.9% in the United States (4) . Significant morbidity is associated with adolescent bipolar disorder, with wide-reaching negative consequences such as poor academic performance, disruptions in family social relations, substance abuse, hospitalizations, and a high rate of mortality because of suicide (3 , 5 – 8) .

A number of open-label, prospective studies have examined pharmacological treatments for children and adolescents with bipolar mania (9 – 16) ; however, the lack of adequately powered controlled trials has made it difficult to evaluate their effectiveness and safety. In one placebo-controlled trial, treatment with oxcarbazepine was not more effective than placebo (17) . In another placebo-controlled trial, which examined treatment with topiramate, results were inconclusive, in part because of a limited sample size (18) . A small, double-blind, placebo-controlled study found that quetiapine in combination with divalproex was more effective for the treatment of adolescent bipolar mania compared with divalproex alone (19) . We conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial to examine the safety and efficacy of olanzapine in the treatment of bipolar mania in adolescents.

Method

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted from November 2002 to May 2005 in the United States (24 sites) and Puerto Rico (two sites). Study settings included university medical centers, outpatient clinics, and private practices.

Patients

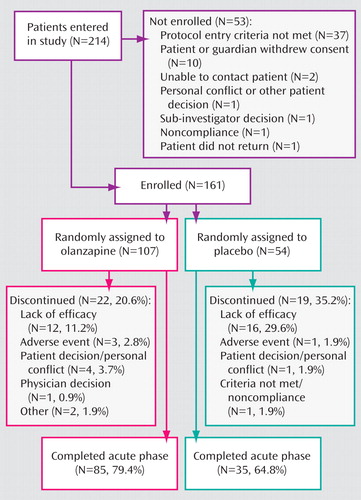

The study enrolled 161 male and female patients 13–17 years of age ( Figure 1 ). All subjects met diagnostic criteria for manic or mixed bipolar episodes (with or without psychotic features) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition-Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR 2000) and confirmed with the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children—Present and Lifetime Version (20) . Subjects were inpatients and outpatients with a total score ≥20 on the Adolescent Structured Young Mania Rating Scale (21) . Exclusion criteria included prior nonresponse to olanzapine, treatment within the previous 30 days with an experimental medication that was not available for clinical use, serious suicidal risk, clinically significant abnormal laboratory values at baseline, DSM-IV-TR substance dependence (except nicotine and caffeine) within the past 30 days, or treatment with a long-lasting neuroleptic within 14 days prior to randomization.

Concomitant use of benzodiazepines/hypnotics was allowed (≤2 mg lorazepam equivalents/day, not to exceed 3 consecutive days). Episodic use of anticholinergics was also permitted (2–6 mg/day) to treat extrapyramidal symptoms. However, prophylactic use was not permitted. Psychostimulant use was permitted as long as the same dose was maintained for at least 30 days prior to randomization and was not altered during the study.

Written informed consent was obtained from patients and their legal guardians prior to participation in the study. The appropriate ethics review boards approved the study before recruitment.

Study Design

The study consisted of the following three periods: period I, screening/washout of 2–14 days; period II, 3-week double-blind, acute treatment with two assessments during the first week of double-blind therapy and weekly thereafter; and period III, 26-week open-label olanzapine treatment. Only results pertaining to the 3-week double-blind period are presented in this article.

All previous mood stabilizers or antimanic drugs were tapered during washout to ensure that patients were free of these medications for at least 2 days before randomization. Antidepressants had to be discontinued at least 7 days prior to randomization, with the exception of monamine oxidase inhibitors (at least 14 days prior to randomization) and fluoxetine (at least 5 weeks prior to randomization). To ensure patient safety, hospitalization for the primary study condition was allowed at the discretion of the investigator.

During the double-blind period, patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive olanzapine (2.5–20.0 mg/day) or placebo. A 2:1 ratio was chosen for ethical reasons to minimize the exposure of acutely manic patients to placebo. Patients in the olanzapine group received a starting dosage of 2.5 mg/day or 5.0 mg/day, which could subsequently be increased by 2.5 mg/day or 5.0 mg/day increments at the investigator’s discretion. Patients in either study group who did not adequately respond to treatment after at least 10 days could enter the 6-month open-label olanzapine phase at the investigator’s discretion without breaking previous double-blind assignment. All patients entering the open-label phase initially received a 2.5 mg/day or 5 mg/day dose of olanzapine, which could subsequently be increased up to 20 mg/day. No additional medications were allowed during the open-label phase. A nonresponse was defined in the protocol as having a <20% reduction in the Young Mania Rating Scale total score relative to baseline and a Clinical Global Impressions—Bipolar Version severity of mania score >3. All 16 patients receiving placebo and 10 of the 12 olanzapine-treated patients who discontinued because of a lack of efficacy entered the open-label phase.

Assessments

The primary efficacy variable was the mean change from baseline to endpoint in the Young Mania Rating Scale total score. At each scheduled visit, Young Mania Rating Scale assessments were obtained from both the patient and parent/legal guardian; on items in which scores were discrepant between assessments, the more severe score was used. Secondary efficacy variables included baseline-to-endpoint changes on the Young Mania Rating Scale individual items; Clinical Global Impressions—Bipolar Version overall, severity of mania, or depression subscales (22) ; Children’s Depression Rating Scale—Revised (23) ; Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Rating Scale-IV—Parent Version (24) ; and Overt Aggression Scale (25) . Additional efficacy measures included rates of response (≥50% decrease in the Young Mania Rating Scale total score from baseline to endpoint) and remission (Young Mania Rating Scale total score ≤12 at endpoint). The incidence of switch to depression (Clinical Global Impressions depression score ≤3 at baseline and ≥4 at any time during the double-blind phase) was also assessed.

The efficacy of olanzapine in patients with distinct illness characteristics or comorbidities was investigated further in the following subgroups: comorbid ADHD or oppositional defiant disorder, mania type, rapid cycling (as defined by DSM-IV), psychotic features, and age of onset. The Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children—Present and Lifetime Version was used to determine a current or lifetime history of ADHD or oppositional defiant disorder.

Safety was assessed by evaluating between-group differences for treatment-emergent adverse events and changes (mean and/or categorical) in vital signs, electrocardiogram (ECG) findings, laboratory values, or extrapyramidal symptoms from baseline to endpoint or at any time. Fasting (≥8 hours) glucose and lipid parameters were collected at randomization and at endpoint. Treatment-emergent categorical changes in lipid parameters were defined using National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria, changes in glucose parameters using American Diabetes Association criteria, and changes in prolactin parameters using both sex and age norm data (females: 4–12 years=2.6–21.0 ng/ml, 12–14 years=2.5–16.9 ng/ml, 14–18 years=4.2–39.0 ng/ml; males: 4–12 years=2.6–21.0 ng/ml, 12–14 years=2.8–24.0 ng/ml, 14–18 years=2.8–16.1 ng/ml). Criteria for other treatment-emergent abnormal laboratory values were defined using Covance reference ranges. Extrapyramidal symptoms were assessed using the Simpson-Angus Scale (26) , the Barnes Akathisia Scale (27) , and the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (28) . All adverse events were recorded as actual terms and coded to Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities terms. Study medication compliance was assessed at each visit by direct questioning and study drug accountability.

Statistical Methods

All patient data were analyzed on an intent-to-treat basis. Baseline frequencies were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Baseline means were compared by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with treatment and country as the independent factors for the continuous data. Exact Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test was used to compare baseline means when the distributions of the residual errors were not normal.

For analysis of last-observation-carried-forward mean change from baseline to endpoint, patients with baseline and at least one postbaseline measurements were included in the analysis. Changes in continuous efficacy data were analyzed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models, which included terms for baseline Young Mania Rating Scale total score, country, and treatment. All reported Young Mania Rating Scale, Clinical Global Impressions—Bipolar Version, Children’s Depression Rating Scale—Revised, ADHD Rating Scale-IV, and Overt Aggression Scale mean change scores represent least squares means. Analysis of visit-wise Young Mania Rating Scale total scores used a mixed-effects model repeated-measures method, which included independent factors for baseline, therapy, country, visit, and therapy-by-visit interaction. Estimates of effect size for rates of response and remission using relative risk and number needed to treat were calculated with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Time to response and remission of mania were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier technique. Mean baseline-to-endpoint changes for continuous safety measures were analyzed using ANOVA models, which included terms for country and treatment. Estimates of treatment effects on weight gain ≥7% of baseline and abnormally high prolactin levels were calculated using number needed to harm.

All tests of hypotheses used a two-sided alpha=0.05, whereas treatment-by-subgroup interactions used alpha=0.10 (SAS software version 8.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C.). No statistical adjustments were made for multiple comparisons of secondary or safety measures. For safety measures, adjustments for multiple comparisons would have made the requirement for statistical significance too stringent, potentially introducing type II errors and missing small but clinically meaningful safety signals.

Results

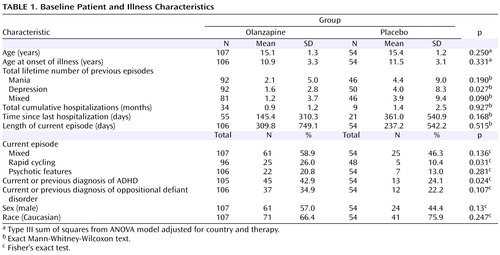

A total of 161 patients were randomly assigned to receive olanzapine (N=107) or placebo (N=54). There were no statistically significant group differences in baseline demographic characteristics ( Table 1 ).

A significantly greater number of patients receiving placebo relative to olanzapine-treated patients discontinued because of lack of efficacy (29.6% versus 11.2%, p=0.007). Three patients treated with olanzapine (increased heart rate, elevated hepatic enzymes, and weight gain) and one patient receiving placebo (pregnancy) discontinued because of an adverse event.

The mean modal dose of olanzapine during the double-blind period was 10.7 mg/day (SD=4.5), and the mean daily dose was 8.9 mg. No significant group differences were observed in the incidence of benzodiazepine use (olanzapine: 12.1% versus placebo: 7.4%, p=0.426) or mean daily dose (olanzapine: 1.44 mg [SD=1.53] versus placebo: 2.05 mg [SD=1.66], p=0.227); however, the placebo group received benzodiazepines for longer periods of time (10.0 days [SD=6.98] versus 2.85 days [SD=3.53], p=0.019). Rates of anticholinergic medication use did not differ significantly between the olanzapine and placebo groups (4.7% versus 0%, p=0.169).

Efficacy

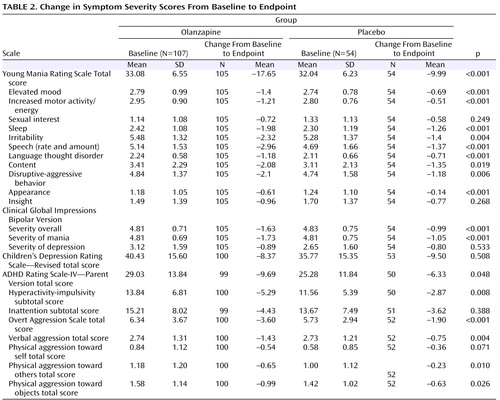

The mean baseline to last-observation-carried-forward endpoint change in the Young Mania Rating Scale total score was significantly greater for the olanzapine group relative to the placebo group (–17.65 versus –9.99, p<0.001; effect size=0.84). The olanzapine group also had significantly greater mean changes in Clinical Global Impressions—Bipolar Version overall (–1.63 versus –0.99, p<0.001) and Clinical Global Impressions—Bipolar Version severity of mania (–1.73 versus –1.05, p<0.001) scores relative to the placebo group. Inclusion of study site as an independent factor in the statistical model did not significantly alter the results of the analyses. Furthermore, when baseline factors for which significant baseline differences were observed (i.e., number of previous depressive episodes, rapid cycling, current diagnosis of ADHD) were included in the ANCOVA model, outcomes of the analyses were not significantly altered.

Statistically significant separation between the olanzapine and placebo groups was observed at the 1-week time point and onward, but not at the -week time point. The mean baseline to last-observation-carried-forward endpoint improvements in nine out of 11 individual Young Mania Rating Scale items scores showed significantly greater statistical difference in the olanzapine group relative to the placebo group ( Table 2 ). The mean improvements from baseline to last-observation-carried-forward endpoint also showed significantly greater statistical difference for patients receiving olanzapine compared with patients receiving placebo on a number of secondary efficacy scales ( Table 2 ).

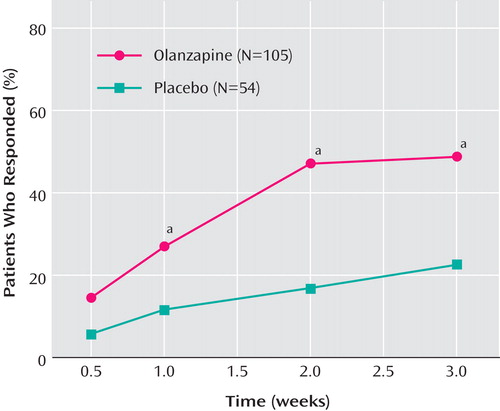

Rates of response and remission were significantly higher for olanzapine patients relative to placebo patients (response: 48.6% versus 22.2%, p=0.002, relative risk=2.19, 95% CI=1.28–3.74, number needed to treat=3.80, 95% CI=2.44–8.54; remission: 35.2% versus 11.1%, p=0.001, relative risk=3.17, 95% CI=1.43–7.04, number needed to treat=4.14, 95% CI=2.74–8.53). Visit-wise response rates are shown in Figure 2 . Times-to-reach response and remission criteria were significantly shorter for patients receiving olanzapine compared with patients receiving placebo (response: p=0.003; remission: p=0.002, log-rank test).

a Denotes statistically significant differences between treatment groups (p<0.05).

The incidence of switch to depression did not differ significantly between the two study groups (olanzapine: 8.2%; placebo: 14.3%, p=0.480; Fisher’s exact test), and there was no significant difference in the time to switch to depression. Furthermore, mean changes from baseline to endpoint in scores from scales of depressive symptom severity did not differ significantly between olanzapine and placebo subjects.

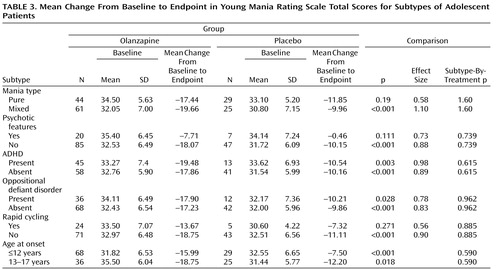

Subgroup Analyses

Mean changes from baseline to endpoint in the Young Mania Rating Scale total score did not differ significantly between patients receiving olanzapine and patients receiving placebo for any of the subgroups (no significant therapy-by-subgroup interactions) ( Table 3 ). For the subgroups of patients with psychotic features and rapid cycling, treatment group differences were not significant, but the sample populations were small.

Concomitant psychostimulant use (yes: N=25; no: N=134) did not differentially affect changes in Young Mania Rating Scale scores (yes: –12.94 versus –6.73; no: –18.06 versus –10.19; therapy-by-psychostimulant use: p=0.959).

Safety

Adverse events

The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events reported with a frequency ≥5% was significantly higher in the olanzapine group for appetite increase, weight increase, and somnolence and sedation items. During the double-blind study period, four serious adverse events occurred in three olanzapine-treated patients (two patients experienced exacerbation of bipolar disorder and one patient had decreased neutrophil count and decreased white blood cell count); none occurred in the placebo group. No deaths occurred during the study.

Vital signs and weight

Significantly greater baseline-to-endpoint increases in supine systolic blood pressure (3.61 [SD=10.40] versus –2.28 [SD=11.26], p=0.001), supine pulse (9.51 [SD=14.53] versus –0.67 [SD=12.52], p<0.001), and standing pulse (8.90 [SD=16.72] versus –1.35 [SD=14.52], p<0.001) were observed in the olanzapine group relative to the placebo group. Mean baseline-to-endpoint increases in weight (3.66 kg [SD=2.18] versus 0.30 kg [SD=1.67], p<0.001) and body mass index (1.18 [SD=0.85] versus 0.02 [SD=0.62], p<0.001) were significantly greater in the olanzapine group relative to the placebo group. Visit-wise changes in body weight and body mass index are shown in Figure 3 . The incidence of treatment-emergent weight gain ≥7% of baseline was significantly higher in the olanzapine group relative to the placebo group (41.9% versus 1.9%, p<0.001; number needed to harm=2.5, 95% CI=1.99–3.34).

Metabolic parameters

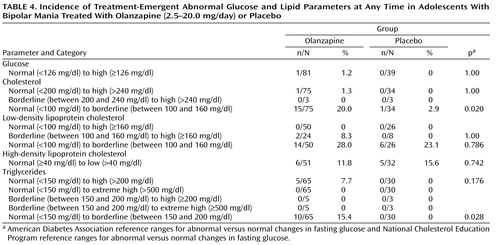

Significantly greater baseline-to-endpoint increases were observed in the olanzapine group relative to the placebo group for fasting glucose (0.15 mg/dl [SD=0.58] versus –0.21 mg/dl [SD=0.21], p=0.002) and fasting total cholesterol (0.37 mg/dl [SD=0.61] versus 0.03 mg/dl [SD=0.75], p=0.010). Using American Diabetes Association and National Cholesterol Education Program criteria for glucose and lipid parameters, respectively, there were no significant differences between the olanzapine and placebo groups in the incidence of treatment-emergent abnormal fasting glucose or lipids at any time during treatment, although the incidence of treatment-emergent normal to borderline-abnormal triglycerides was higher (15.4% versus 0%, p=0.028) ( Table 4 ). However, using Covance reference ranges for total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides, the incidents of treatment-emergent abnormally high values at any time were significantly higher for the olanzapine group relative to the placebo group (total cholesterol: 19.1% versus 2.1%, p=0.004; high-density lipoprotein cholesterol: 10.9% versus 0.0%, p=0.016; and triglycerides: 49.1% versus 14.8%, p=0.003).

Prolactin and other laboratory values

Mean baseline-to-endpoint increases in prolactin were significantly greater in the olanzapine group relative to the placebo group (females: 15.38 ng/ml [SD=13.73] versus 2.67 ng/ml [SD=8.60], p<0.001; males: 11.50 ng/ml [SD=9.50] versus 0.66 ng/ml [SD=3.06], p<0.001). The incidence of treatment-emergent abnormally high levels of prolactin was significantly higher in patients receiving olanzapine compared with patients receiving placebo (females: 25.7% versus 0%, p=0.007, number needed to harm=3.89, 95% CI=2.49–8.90; males: 62.5% versus 5%, p<0.001, number needed to harm=1.74, 95% CI=1.35–2.45). Mean baseline-to-endpoint increases in hepatic enzymes were significantly greater in the olanzapine group relative to the placebo group (aspartate transaminase: 7.41 [SD=20.95] versus –1.62 [SD=5.74] U/liter, p=0.002; alanine transaminase:19.53 [SD=50.23] versus –1.28 [SD=8.60] U/liter, p=0.003). The incidence of treatment-emergent abnormally high levels of aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase at any time was significantly higher in patients receiving olanzapine compared with patients receiving placebo (aspartate transaminase: 22.4% versus 2.0%, p<0.001; alanine transaminase: 33.7% versus 2.1%, p<0.001, number needed to harm=14.96, 95% CI=7.59–507.42). Increases in uric acid were significantly greater in the olanzapine group relative to the placebo group (21.04 mmol/liter [SD=52.39] versus 0.60 mmol/liter [SD=56.97], p=0.026).

ECG

Mean baseline-to-endpoint increases in heart rate were significantly greater in patients receiving olanzapine compared with patients receiving placebo (9.80 bpm [SD=12.46] versus –3.61 bpm [SD=10.38], p<0.001). Mean change from baseline to endpoint in Fridericia-adjusted QTc interval did not differ significantly between the olanzapine and placebo groups (2.28 msec [SD=15.64] versus 1.62 msec [SD=14.84], p=0.808).

Extrapyramidal Symptoms

No significant differences were observed between the two study groups on the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (olanzapine, –0.10 [SD=0.71] versus placebo, 0.00 [SD=0.19], p=0.289), Simpson-Angus (olanzapine, 0.02 [SD=0.93] versus placebo, –0.02 [SD=0.14], p=0.769), or Barnes scales (olanzapine, –0.04 [SD=0.44] versus placebo, 0.06 [SD=0.60], p=0.264).

Suicidality

One report of treatment-emergent suicidal ideation occurred in the olanzapine group, but there were no reports of suicide attempt or self-injurious behavior.

Discussion

Although the use of antipsychotic agents for bipolar mania in adolescents has increased markedly (29) , to our knowledge this is the first adequately powered placebo-controlled study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of any antipsychotic agent in this patient population.

Patients treated with olanzapine experienced greater reductions in the severity of affective symptoms relative to patients receiving placebo, as reflected by the significantly greater mean decreases in Young Mania Rating Scale total, Clinical Global Impressions—Bipolar Version overall severity, and Clinical Global Impressions—Bipolar Version severity of mania scores. Furthermore, the greater efficacy of olanzapine relative to placebo was evident across most of the subgroups of patients analyzed.

The present study is distinguished from previous investigations of treatments for adolescent bipolar mania, which, for the most part, were not placebo-controlled, involved small patient populations, and allowed use of concomitant medications. These differences, however, preclude meaningful comparisons of treatment efficacy with findings from studies in adolescents previously reported in the literature. The efficacy of olanzapine for the treatment of bipolar mania in adults has been examined in two double-blind, placebo-controlled studies (30 , 31) , and findings from these studies may provide useful points of comparison. However, these comparisons should also be tempered by an acknowledgment of potentially important differences, such as starting (2.5 mg versus 10 or 15 mg) and mean daily (8.9 mg versus 14.9 or 16.4 mg) doses of olanzapine and study duration (3 versus 4 weeks in one study).

The rates of study completion among adolescent patients treated with olanzapine were notably higher compared with corresponding rates among adult patients (79.4% versus 61.4% and 61.8%), while discontinuation rates because of lack of efficacy were lower (11.2% versus 28.6% and 27.3%) (30 , 31) . A point difference of 7.66 in mean baseline-to-endpoint change in the Young Mania Rating Scale score was observed between adolescent patients receiving olanzapine or placebo, with a corresponding effect size of 0.84, compared with 0.46 and 0.53 in the adult studies (28 , 29) . The response rates observed in adolescent patients (olanzapine: 48.6%; placebo: 22.2%) are comparable with those reported by Tohen et al. in one study (30) (olanzapine: 48.6%; placebo: 24.2%) in adult patients, but somewhat lower for both the olanzapine group and the placebo group in another study (31) (olanzapine: 64.8%; placebo: 42.9%). It should be noted, however, that the latter study was 4 weeks in duration, which may account in part for the higher response rates.

Significant differences were observed between patients treated with olanzapine and patients receiving placebo regarding mean baseline-to-endpoint changes in fasting glucose and total cholesterol. Based on the Covance reference ranges, the incidents of treatment-emergent abnormally high levels of fasting total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides were significantly higher for patients receiving olanzapine relative to patients receiving placebo. Increases in prolactin levels were observed in adolescents but not in the adult studies (30 , 31) . Increased prolactin levels have been reported previously during treatment with various typical and atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents (32 – 34) , and it has been suggested that adolescents may be more susceptible to treatment-emergent elevations in prolactin (35) ; however, the health impact of elevated prolactin is still unclear. The incidence of treatment-emergent abnormally high aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase values at any time during the double-blind period was significantly higher in adolescent patients treated with olanzapine relative to adolescent patients receiving placebo. Similar increases in alanine transaminase values have been observed in adult patients treated with olanzapine (30 , 31) , although they appear to be asymptomatic and transient in nature (36) . It is, however, uncertain whether a similar transient course occurs in adolescent patients. Furthermore, the long-term consequences of these increases in liver enzymes in adolescents are unclear.

Weight gain has been documented previously in adult patients suffering from bipolar mania treated with olanzapine; however, mean weight gain was greater in this group of adolescent patients (adolescents: 3.66 kg; adults:1.65 kg [30] and 2.11 kg [31] ). Age-related differences in weight gain during treatment with atypical antipsychotics have been reported elsewhere (37 – 40) , with a greater susceptibility observed among children and adolescents; however, the reasons are not yet understood. The need to recognize and develop mitigation strategies around issues of weight gain and potential metabolic dysregulation has been highlighted in a recent review of atypical antipsychotic medications in adolescent patients (41) . The significant weight gain observed during this short, 3-week trial raises concerns about potential negative consequences of prolonged treatment with olanzapine, particularly in the proportion of patients who experienced rapid weight increase. For these patients, other options should be considered depending on the efficacy and tolerability of alternative treatments. A risk-benefit ratio or likelihood of help or harm derived from number-needed-to-harm and number-needed-to-treat estimates around weight gain and treatment response (2.50/3.80=0.66) suggests that although the probability of responding is good, the probability of gaining weight is even greater. In the absence of data from long-term studies with olanzapine or other treatments, the risk-benefit ratio over longer treatment periods remains to be determined in this patient population.

There were several limitations to this study. The trial characterizes only a brief window in the course of treatment for bipolar disorder and was designed to balance the need for a reasonable time interval to determine efficacy and safety with ethical concerns of treating patients experiencing an acute manic episode with placebo. Furthermore, an option to discontinue the double-blind phase and enter the open-label phase after 10 days was provided out of safety concerns for patients who did not respond to treatment, which may have accounted for the significantly higher discontinuation rate among patients receiving placebo.

The benefits of olanzapine for the treatment of acute manic episodes in adolescents should be considered within the context of its safety profile as observed in this study. Changes in several parameters identified as risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diabetes were observed in adolescent patients treated with olanzapine. Overall, the types of adverse events appeared to be similar to those reported in adults, although weight, metabolic, and prolactin changes may be greater in adolescents. However, given its short duration, this trial cannot answer questions regarding the long-term safety or efficacy of olanzapine in the adolescent population.

1. Costello EJ, Angold A, Burns BJ, Stangl DK, Tweed DL, Erkanli A, Worthman CM: The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth: goals, design, methods, and the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:1129–1136Google Scholar

2. Johnson JG, Cohen P, Brook JS: Associations between bipolar disorder and other psychiatric disorders during adolescence and early adulthood: a community-based longitudinal investigation. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1679–1681Google Scholar

3. Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Seeley JR: Bipolar disorders in a community sample of older adolescents: prevalence, phenomenology, comorbidity, and course. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:454–463Google Scholar

4. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62:593–602Google Scholar

5. Geller B, Craney JL, Bolhofner K, Nickelsburg MJ, Williams M, Zimerman B: Two-year prospective follow-up of children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:927–933Google Scholar

6. Strober M, Carlson G: Bipolar illness in adolescents with major depression: clinical, genetic, and psychopharmacologic predictors in a three- to four-year prospective follow-up investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:549–555Google Scholar

7. Strober M, Schmidt-Lackner S, Freeman R, Bower S, Lampert C, DeAntonio M: Recovery and relapse in adolescents with bipolar affective illness: a five-year naturalistic, prospective follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:724–731Google Scholar

8. Wozniak J, Biederman J, Kiely K, Ablon JS, Faraone SV, Mundy E, Mennin D: Mania-like symptoms suggestive of childhood-onset bipolar disorder in clinically referred children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:867–876Google Scholar

9. Biederman J, Mick E, Wozniak J, Aleardi M, Spencer T, Faraone SV: An open-label trial of risperidone in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2005; 15:311–317Google Scholar

10. DeLong GR, Nieman GW: Lithium-induced behavior changes in children with symptoms suggesting manic-depressive illness. Psychopharmacol Bull 1983; 19:258–265Google Scholar

11. Frazier JA, Biederman J, Tohen M, Feldman PD, Jacobs TG, Toma V, Rater MA, Tarazi RA, Kim GS, Garfield SB, Sohma M, Gonzalez-Heydrich J, Risser RC, Nowlin ZM: A prospective open-label treatment trial of olanzapine monotherapy in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2001; 11:239–250Google Scholar

12. Kafantaris V, Coletti DJ, Dicker R, Padula G, Kane JM: Lithium treatment of acute mania in adolescents: a large open trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42:1038–1045Google Scholar

13. Kowatch RA, Suppes T, Carmody TJ, Bucci JP, Hume JH, Kromelis M, Emslie GJ, Weinberg WA, Rush AJ: Effect size of lithium, divalproex sodium, and carbamazepine in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:713–720Google Scholar

14. Masi G, Mucci M, Millepiedi S: Clozapine in adolescent inpatients with acute mania. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2002; 12:93–99Google Scholar

15. Papatheodorou G, Kutcher SP, Katic M, Szalai JP: The efficacy and safety of divalproex sodium in the treatment of acute mania in adolescents and young adults: an open clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1995; 15:110–116Google Scholar

16. Varanka TM, Weller RA, Weller EB, Fristad MA: Lithium treatment of manic episodes with psychotic features in prepubertal children. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:1557–1559Google Scholar

17. Wagner KD, Kowatch RA, Emslie GJ, Findling RL, Wilens TE, McCague K, D’Souza J, Wamil A, Lehman RB, Berv D, Linden D: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of oxcarbazepine in the treatment of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1179–1186Google Scholar

18. DelBello MP, Findling RL, Kushner S, Wang D, Olson WH, Capece JA, Fazzio L, Rosenthal NR: A pilot controlled trial of topiramate for mania in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44:539–547Google Scholar

19. DelBello MP, Schwiers ML, Rosenberg HL, Strakowski SM: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine as adjunctive treatment for adolescent mania. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:1216–1223Google Scholar

20. Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 36:980–988Google Scholar

21. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA: A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity, and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:429–435Google Scholar

22. Spearing MK, Post RM, Leverich GS, Brandt D, Nolen W: Modification of the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) scale for use in bipolar illness (BP): the CGI-BP. Psychiatry Res 1997; 73:159–171Google Scholar

23. Poznanski E, Mokros HB: Children’s Depression Rating Scale, Revised. Los Angeles, Western Psychological Services, 2005Google Scholar

24. DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, Reid R: ADHD Rating Scale-IV: Checklist, Norms, and Clinical Interpretations. Bethlehem, Pa, Lehigh University, 2005Google Scholar

25. Yudofsky SC, Silver JM, Jackson W, Endicott J, Williams D: The Overt Aggression Scale for the objective rating of verbal and physical aggression. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:35–39Google Scholar

26. Simpson GM, Angus JWS: A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1970; 212:S11–S19Google Scholar

27. Barnes TR: A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 154:672–676Google Scholar

28. Guy W: ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, Revised, Publication ADM 76–338. Bethesda, Md, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976Google Scholar

29. Olfson M, Blanco C, Liu L, Moreno C, Laje G: National trends in the outpatient treatment of children and adolescents with antipsychotic drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63:679–685Google Scholar

30. Tohen M, Sanger TM, McElroy SL, Tollefson GD, Chengappa KN, Daniel DG, Petty F, Centorrino F, Wang R, Grundy SL, Greaney MG, Jacobs TG, David SR, Toma V: Olanzapine versus placebo in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:702–709Google Scholar

31. Tohen M, Jacobs TG, Grundy SL, Banov MC, McElroy SL, Janicak PG, Zhang F, Toma V, Francis BJ, Sanger TM, Tollefson GD, Breier A: Efficacy of olanzapine in acute bipolar mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:841–849Google Scholar

32. Alfaro CL, Wudarsky M, Nicolson R, Gochman P, Sporn A, Lenane M, Rapoport JL: Correlation of antipsychotic and prolactin concentrations in children and adolescents acutely treated with haloperidol, clozapine, or olanzapine. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2002; 12:83–91Google Scholar

33. Pappagallo M, Silva R: The effect of atypical antipsychotic agents on prolactin levels in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2004; 14:359–371Google Scholar

34. Saito E, Correll CU, Gallelli K, McMeniman M, Parikh UH, Malhotra AK, Kafantaris V: A prospective study of hyperprolactinemia in children and adolescents treated with atypical antipsychotic agents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2004; 14:350–358Google Scholar

35. Wudarsky M, Nicolson R, Hamburger SD, Spechler L, Gochman P, Bedwell J, Lenane MC, Rapoport JL: Elevated prolactin in pediatric patients on typical and atypical antipsychotics. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1999; 9:239–245Google Scholar

36. Beasley CM Jr, Tollefson GD, Tran PV: Safety of olanzapine. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58(suppl 10):13–17Google Scholar

37. Hellings JA, Zarcone JR, Crandall K, Wallace D, Schroeder SR: Weight gain in a controlled study of risperidone in children, adolescents and adults with mental retardation and autism. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2001; 11:229–238Google Scholar

38. Ratzoni G, Gothelf D, Brand-Gothelf A, Reidman J, Kikinzon L, Gal G, Phillip M, Apter A, Weizman R: Weight gain associated with olanzapine and risperidone in adolescent patients: a comparative prospective study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41:337–343Google Scholar

39. Safer DJ: A comparison of risperidone-induced weight gain across the age span. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004; 24:429–436Google Scholar

40. Sikich L, Hamer RM, Bashford RA, Sheitman BB, Lieberman JA: A pilot study of risperidone, olanzapine, and haloperidol in psychotic youth: a double-blind, randomized, 8-week trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004; 29:133–145Google Scholar

41. Correll CU, Carlson HE: Endocrine and metabolic adverse effects of psychotropic medications in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006; 45:771–791Google Scholar