Lifetime and 12-Month Prevalence of DSM-III-R Disorders in the Chile Psychiatric Prevalence Study

Abstract

Objective: Although several epidemiological studies of the prevalence of psychiatric disorders have been conducted in Latin America, few of them were national studies that could be used to develop region-wide estimates. Data are presented on the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders, demographic correlates, comorbidity, and service utilization in a nationally representative adult sample from Chile. Method: The Composite International Diagnostic Interview was administered to a stratified random sample of 2,978 individuals from four provinces representative of the country’s population age 15 and older. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence rates were estimated. Results: Approximately one-third (31.5%) of the population had a lifetime psychiatric disorder, and 22.2% had a disorder in the past 12 months. The most common lifetime psychiatric disorders were agoraphobia (11.1%), social phobia (10.2%), simple phobia (9.8%), major depressive disorder (9.2%), and alcohol dependence (6.4%). Of those with a 12-month prevalence diagnosis, 30.1% had a comorbid psychiatric disorder. The majority of those with comorbidity had sought out mental health services, in contrast to one-quarter of those with a single disorder. Conclusions: The prevalence rates in Chile are similar to those obtained in other studies conducted in Latin America and Spanish-speaking North American groups. Comorbidity and alcohol use disorders, however, were not as prevalent as in North America.

The relative burden of mental illness has markedly changed from 1990 to 2002 in Latin America as an epidemiological transition has taken hold in the region, away from the exclusive focus on infectious diseases. It is estimated that mental illness currently accounts for 22% of the disease burden (disability-adjusted life years) in Latin America and 40% of the years lived with disability, in contrast to 8.2% and 33.2%, respectively, in 1990 (1) . Major depression is ranked as the leading cause of disease burden and the highest cause of years lived with disability for both sexes combined and for women. Alcohol use disorders are ranked as the fourth-highest cause of years with disability, and the second-highest for disability-adjusted life years. For men, alcohol disorders rank as the second most important cause of disability-adjusted life years and the highest of all disorders for years lived with disability. These estimates of disability associated with mental illness have been based on epidemiological data from selected Latin American countries.

Latin America has a rich tradition of conducting research in psychiatric epidemiology using both symptom scales and third-generation structured diagnostic instruments (2) . Unfortunately, many of the third-generation studies (3) examining rates of psychiatric disorders have not been widely cited, in part because the results frequently are not published in English-language journals.

The Chile Psychiatric Prevalence Study was developed to address issues regarding the prevalence and risk factors for mental illness based on a nationally representative sample. This report focuses on the lifetime and 12-month prevalence rates of disorders and their association with sociodemographic correlates. The study also examined comorbidity and service utilization.

Method

Sample Selection

The study was based on a household stratified sample of persons age 15 and older. In Chile, individuals age 15 and older are considered adults within the health service system. The study was designed to represent the national population of the country. Chile has a population of approximately 14 million people. The two largest cities, Santiago and Concepción, are in the central region. The country is composed of 51 provinces grouped in 13 regions covering an area of 2 million km 2 (including Antarctica and Insular Territories) over a length of 8,000 km. In this study, the sample was selected from four provinces that represent geographically distinct regions of the country and was representative of the distribution of the national population: Santiago, Concepción, Iquique, and Cautín.

Santiago is the country’s capital and accounts for one-third of the nation’s population. Concepción is the second-largest city. The northern part of the country, which includes the province of Iquique, is isolated by desert with towns that are distant from each other. Although Chile is primarily urban, the southern part of the country, including the province of Cautín, is mainly rural. Cautín also has a high concentration of indigenous people.

In Chile, provinces are subdivided into comunas, subsequently into districts, and then into blocks, which were selected randomly. The households available on each block were counted. The 1992 national census was used to determine the number of households required on each block. The households were chosen clockwise, starting with the first one on the northeastern corner of each block. The subsequent household selected was based on a number obtained by dividing the census estimate by the number of residences on the block. The person interviewed in a given household was determined by generating a list of all inhabitants 15 and older in descending order by age with males first. By using 12 randomly preassigned Kish tables (4) , one person per household was selected.

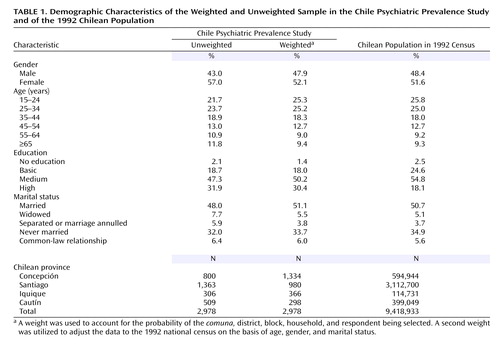

The survey was conducted by the University of Concepción Department of Psychiatry between July 1992 and June 1999, with each site being completed in the following order as funding was secured: Concepción, Santiago, Iquique, and Cautín. The response rate was 90.3%, and a total of 2,978 individuals participated in the survey. The response rate did differ by site (χ 2 =11.08, df=3, p<0.02); Santiago had the lowest response rate (87.4%), and Iquique had the highest (92.5%). The response rate may have been enhanced by advertisements on the radio and television and in newspapers, letters written to the household by the city mayor, and meetings of the investigators with potential refusers in each of the sites. A weight was used to account for the probability of the comuna, district, block, household, and respondent being selected. A second weight was utilized to adjust the data to the 1992 national census on the basis of age, gender, and marital status. A comparison of weighted and unweighted data with national distributions on demographic variables is presented in Table 1 .

Diagnostic Assessment

The psychiatric diagnoses are based on DSM-III-R. The diagnostic interview used to generate these diagnoses was the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (5) , versions 1.0 and 1.1. The CIDI is a structured diagnostic interview schedule for use by well-trained lay interviewers. Prevalence periods are based on the onset and cessation of self-reported symptoms. In addition, the sections of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (6) on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and antisocial personality disorder were included, as these disorders were not included in those versions of the CIDI. There is much resemblance in the structure and administration of the two instruments as the DIS preceded the development of the CIDI. The DIS sections were not administered in Cautín. The interview schedule also had a section on health service utilization in the 6 months before the interview that was linked to the period of inquiry about psychiatric symptoms.

The instruments were translated into Spanish by using the protocol outlined by the World Health Organization (WHO) (7) . The CIDI version used became an approved WHO Spanish version of the CIDI. The CIDI was validated in 120 patients from the local psychiatric services who were diagnosed by clinical psychiatrists using a DSM-III-R checklist. At least 10 representative patients were selected for each of the CIDI sections. In addition, 10 adult volunteers with no known psychiatric disorder were also included in the validation study. The psychiatrists who administered the CIDI were blind to the psychiatric status of these individuals. The kappas ranged from 0.52 for somatoform disorders to 0.94 for affective disorders (8) . The DIS was translated and validated (9) by using similar procedures, with kappas of 0.72 for antisocial personality disorder and 0.63 for PTSD.

The DSM-III-R diagnoses included were major depression, mania, dysthymia, panic disorder, agoraphobia, alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse, drug dependence, nicotine dependence, antisocial personality disorder, somatoform disorders, and nonaffective psychoses. Nonaffective psychoses is a summary category consisting of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, and atypical psychosis. The CIDI sections for eating disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, simple phobia, and social phobia were not included in the first two sites and therefore are not represented in the overall rates of anxiety disorders or in the “any disorder” category. The CIDI computer programs for versions 1.0 and 1.1 were used to generate the diagnoses (10) in accordance with a procedure using double data entry and with verification for logical inconsistencies.

Interviewers and Training

The 64 interviewers were all university students in their senior year who were studying social sciences. They did not include medical students or physicians because of the potential for respondents to misinterpret questions about last seeing a health care professional. The University of Concepción is a WHO CIDI training and reference center. Training was conducted according to the WHO protocol and consisted of over 80 hours of instruction and practice sessions. In order to complete the training, each interviewer had to conduct practice interviews with volunteer adult subjects with and without psychiatric disorders selected from local clinics. These interviews were audiotaped and reviewed with the trainers. In addition, the interviewers had to each complete a pilot interview with an individual in a nonselected household in the community. Only 39% of those originally trained (N=163) were accepted as interviewers.

All of the interviews were audiotaped after consent was given by the subjects, approximately 80% of those asked to participate. The audiotapes from the first three interviews by each interviewer were reviewed for quality, after which about 20% the audiotapes were randomly reviewed to maintain quality control. The audiotapes were used to confirm the accuracy of the interviews and to correct missing and unclear responses. Each interview was edited according to the rules in the CIDI trainer’s manual (11) . Inconsistencies in the interview were corrected by using the audiotapes whenever possible, including those for interviews that were not part of the random quality control. If editing issues could not be clarified, the interviewer was sent back into the field for resolution. In addition, field supervisors randomly selected households and met with the respondents to verify that the interview was conducted in full. This resulted in the reinterviewing of a number of respondents.

Informed Consent

The University of Concepción’s institutional review board approved the study. All of the interviewed respondents provided formal informed consent. The interview schedules did not include the respondent’s name, and all data were processed anonymously. All respondents were given an opportunity to obtain the results of their CIDI interview, and a sizable percentage requested the individualized reports; this procedure may have further enhanced participation.

Analysis Procedures

Because of the sample design and the need for weighting, the SUDAAN statistical package (12) was used to estimate the standard errors. The latter were estimated by using the Taylor series linearization method. The analysis was conducted by means of procedures without replacement for nonrespondents. The region, province, comuna, and district selected were used as the defined strata. Logistic regression with the corresponding 95% confidence interval was used to examine the association with demographic risk factors. All results are presented as weighted data unless otherwise stated.

Results

Prevalence Rate of Psychiatric Disorders

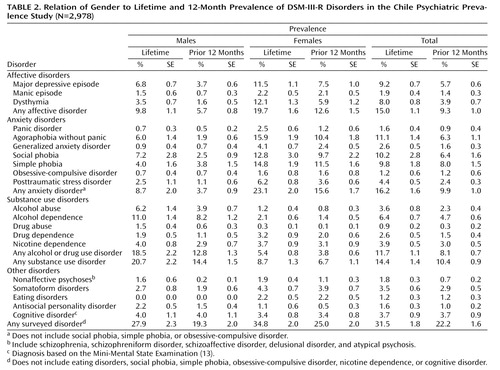

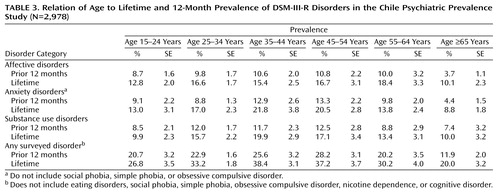

Table 2 and Table 3 show the lifetime and 12-month prevalence rates of the disorders evaluated. The prevalence estimates are presented without application of the exclusion criteria based on DSM-III-R hierarchy rules. The lifetime prevalence rate is defined as the proportion of the sample who ever experienced the disorder, while the 12-month prevalence is the rate of those who experienced the disorder at some point during the year prior to the interview.

Nearly one-third, 31.5%, of the Chilean population had a psychiatric disorder during their lifetime, while one in five, 22.2%, had a disorder in the past 12 months. The most common lifetime psychiatric disorders were agoraphobia, social phobia, simple phobia, major depressive disorder, and alcohol dependence ( Table 2 ). For 12-month prevalence, the five most common disorders were simple phobia, social phobia, agoraphobia, major depressive disorder, and alcohol dependence. The anxiety disorders were the most common group of lifetime psychiatric disorders in the population (16.2%). Substance use disorders were the most common disorders in the preceding 12 months (10.4%).

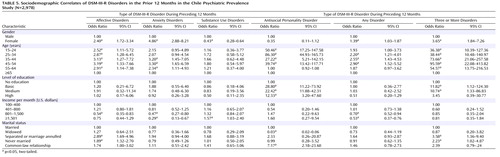

Sociodemographic Correlates of Disorders

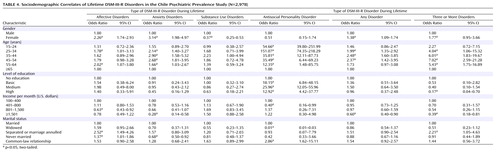

Bivariate risk factor associations for the broad categories of lifetime and 12-month diagnoses are reported in Table 4 and Table 5 , respectively. Affective disorders were more than twice as common among women, while anxiety disorders were more than three times as common; however, substance use disorders were three times as prevalent among men. A higher risk for women was noted in the overall rates of both the lifetime and 12-month prevalence of the disorders examined.

In contrast to individuals 65 years and older, differential risk by age was noted. Most notably, age was not predictive of substance use disorders. For lifetime prevalence, people between the ages of 25 and 64 were noted to be at higher risk for anxiety disorders. Those younger than age 65 were at higher risk for affective disorders in the prior year, while those between the ages of 35 and 64 were at higher risk for anxiety disorders. For both lifetime and 12-month prevalence, people younger than 54 were at higher risk for antisocial personality disorder; among people with a lifetime diagnosis, those between ages 55 and 64 were also at higher risk. A higher risk for any disorder was found among those between 25 and 54 years of age.

An inverse relationship between educational attainment and overall rates of disorders was not elicited. Antisocial personality disorder, however, was less prevalent among people without education. An inverse relationship with lifetime rates for anxiety disorders and any diagnosis was noted for income, with statistically significant differences between the highest and lowest income groups. For 12-month prevalence, both disorders had a clear inverse relationship with income.

Individuals who had never married or who were separated or had their marriages annulled had the highest rates of affective disorders. Those who had never been married had the lowest lifetime rate of anxiety disorders. A statistically significant relationship between anxiety disorders and marital status was not found for 12-month prevalence. Antisocial personality disorder was more common among those in a common-law relationship.

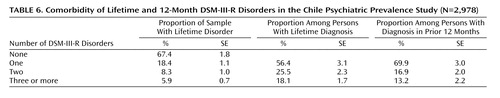

Comorbidity

Two-thirds of the Chilean population had never had a psychiatric disorder. Of those with lifetime psychiatric disorders, the majority had a single diagnosis, while one-quarter had two disorders, and fewer than one-fifth had three or more disorders ( Table 6 ). The proportions were similar for the 12-month prevalence of psychiatric disorders. Lifetime comorbidity of three or more disorders was significantly higher among women, people who were between the ages of 25 and 64, and those who had separated from their spouses or whose marriages had been annulled ( Table 4 ). It was lowest among those with the highest education or income. Comorbidity of three or more disorders in the prior 12 months was more common among women, people younger than 65, those with a basic or medium level of education, and those who had never married, were separated, or had had their marriages annulled ( Table 5 ). All of the respondents diagnosed with PTSD also had generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, or panic disorder.

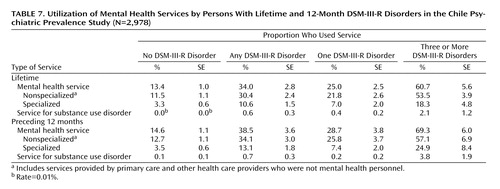

Service Utilization

Only one-quarter of the individuals who had noncomorbid psychiatric disorders had sought any type of mental health care ( Table 7 ). Of those who had three or more diagnoses, the majority had sought some form of mental health treatment. Most individuals with a diagnosis did not receive treatment from specialists. A sizable number of individuals not found to have a psychiatric disorder also had sought services for mental health care.

Discussion

The Chile Psychiatric Prevalence Study survey is one of only a few psychiatric epidemiological prevalence studies of a nationally representative sample in a Latin American country. To our knowledge, it is the first to use appropriate statistical procedures to correct for the sampling design and weights to ensure that the sample is representative of the national population. Approximately one in three individuals in the population had a lifetime psychiatric disorder in Chile, and over one-fifth had a disorder in the past 12 months. The five most common lifetime psychiatric disorders were agoraphobia, social phobia, simple phobia, major depressive disorder, and alcohol dependence. For men the most common disorder was alcohol abuse or dependence, while for women it was an anxiety disorder. Nearly one-third of those with a 12-month prevalence diagnosis had a comorbid psychiatric disorder. The majority of those with comorbidity had sought out mental health services, but only one-quarter of those without comorbidity had done so.

This survey suffers from the same limitations as most other cross-sectional psychiatric prevalence studies. First, the lifetime prevalence rates are based on retrospective reports. Second, the diagnostic assessments relied on the CIDI, which is an interview administered by nonclinicians. In addition, the sample size may not yield enough power to examine risk factors for the less common psychiatric disorders. The lower prevalence of disorders in the elderly, as found in most other epidemiological studies, might be due to a cohort effect, reporting bias, or differential mortality of those with a disorder. The assessment of cognitive impairment was limited to items from the Mini-Mental State Examination (13) and did not include a formal diagnosis of dementia, the most common mental disorder of late life. The interviews conducted in the four catchment areas representing the Chile Psychiatric Prevalence Study were not completed at the same time but, rather, over 7 years. This, unfortunately, is a reflection of the difficulty of obtaining consistent funding to conduct research in developing countries.

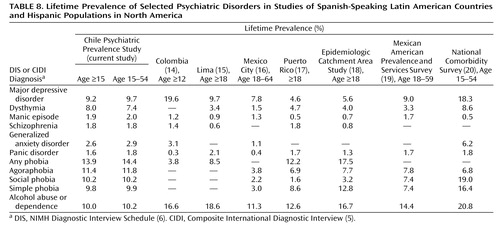

The findings from the Chile Psychiatric Prevalence Study are by and large similar to those found among other Hispanic populations. Table 8 provides a comparison of the current results with the findings from other published studies that used the DIS or CIDI to determine lifetime prevalence rates in Spanish-speaking Latin American countries and Hispanic populations in North America. In contrast to that found among Hispanics in the National Comorbidity Survey (20) in the United States, the rate of major depression in the Chile Psychiatric Prevalence Study, for ages 15–54, was considerably lower, 9.7%, compared to 18.3%, and the rate of alcohol use disorders was also lower, 10.2% versus 20.8%. It is conceivable, but unlikely, that this could be fully explained only by differences in methods, such as the use of additional probes in the National Comorbidity Survey. Except for Colombia (14) , all of the other studies had similar rates for major depressive disorders. In the Colombia study, dysthymia was not considered as a diagnosis, and those individuals may have been included among those with major depression, accounting for the difference in rates. The higher rate of alcohol use disorders in Colombia may be due to the fact that they were identified by using the CAGE (21) as a screening instrument, while the rates in the Lima study (15) may reflect the lower socioeconomic status of the sample. The three studies of Hispanics in the continental United States (18 – 20) consistently show higher rates of alcohol use disorders than were found in the South American surveys. The rate of anxiety disorders in Chile was higher than that for major depression, a finding noted in some but not all studies of Hispanic populations. The low rate of comorbidity in the Chile Psychiatric Prevalence Study was also noted in the Mexico City CIDI study (16) , in marked contrast to the National Comorbidity Survey, in which comorbidity was the norm (20) . Rates of service utilization in the United States (22) , Mexico (16) , and Chile did not appear to differ widely. Although such cross-national comparisons are crude because of differences in methods across studies, with the inclusion of the current study a general picture of the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Latin America is now emerging.

The importance of mental illness in disability and utilization of health care services in Latin America, although increasing, is not yet fully appreciated. Psychiatric epidemiological surveys are a means of providing data to authorities in a position of allocating resources to address the developing crisis in mental health anticipated in Latin America as the epidemiological transition continues (2) . Future studies, however, will need to focus more on service utilization needs, the presence of medical comorbidity, prevalence rates for serious mental illnesses, and measures of disability.

1. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/bodgbd2002revised/en/index.htmlGoogle Scholar

2. Levav I, Lima BR, Somoza-Lenon M, Kramer M, Gonzalez R: Mental health for all in Latin America and the Caribbean: epidemiologic bases for action. Bol Oficina Sanit Panam 1989; 107:196–219Google Scholar

3. Dohrenwend BP, Dohrenwend BS: Perspective on the past and future of psychiatric epidemiology. Am J Public Health 1981; 72:1271–1279Google Scholar

4. Kish L: Survey Sampling. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1965Google Scholar

5. Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen HU, Helzer JE, Babor TF, Burke J, Farmer A, Jablensky A, Pickens R, Regier DA, Sartorius N, Towle LH: The Composite International Diagnostic Interview: an epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:1069–1077Google Scholar

6. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS: National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981; 38:381–389Google Scholar

7. Sartorius N, Kuyken W: Translation of health status instruments, in Quality of Life Assessment in Health Care Settings, vol 1. Edited by Orley J, Kuyken W. Berlin, Springer, 1994, pp 130–143Google Scholar

8. Vielma M, Vicente B, Rioseco P, Castro P, Castro N, Torres S: Validación en Chile de la entrevista diagnóstica estandarizada para estudios epidemiológicos CIDI. Revista de Psiquiatría 1992; 9:1039–1049Google Scholar

9. Rioseco P, Vicente B, Uribe M, Vielma M, Castro N, Torres S: El DIS-III-R: una validación en Chile. Revista de Psiquiatría 1992; 9:1034–1038Google Scholar

10. Pfister H, Wittchen HU: CIDI Core Computer Manual for Data Entry and Diagnostic Programmes for the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Geneva, World Health Organization, 1990Google Scholar

11. Wittchen HU, Semler G: CIDI-Core Training Manual: Description of Procedures for Training in the Use of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Geneva, World Health Organization, 1990Google Scholar

12. Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Bieler GS: SUDAAN User’s Manual, Release 7.5. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 1997Google Scholar

13. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: Mini-Mental State: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975; 12:189–198Google Scholar

14. Torres de Galvis Y, Montoya ID: Segundo Estudio Nacional de Salud Mental y Consumo de Sustancias Psicoactivas Colombia 1997. Bogota, Colombia, Ministry of Health, 1997Google Scholar

15. Yamamoto J, Silva JA, Sasao T, Wang C, Nguyen L: Alcoholism in Peru. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1059–1062Google Scholar

16. Caraveo-Anduaga JJ, Colmenares BE, Saldívar HG: Morbilidad psiquiátrica en la Ciudad de México: prevalencia y comorbilidad a lo largo de la vida (Psychiatric morbidity in Mexico City: prevalence and comorbidity during a lifetime). Salud Mental 1999; 22(suppl):62–67Google Scholar

17. Canino GJ, Bird HR, Shrout PE, Rubio M, Bravo M, Martinez R, Sesman M, Guevara M: The prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in Puerto Rico. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:727–735Google Scholar

18. Robins LN, Regier DA: Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

19. Vega WA, Kolody B, Agular-Gaxiola S, Alderete E, Catalano R, Caraveo-Anduaga J: Lifetime prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among urban and rural Mexican Americans in California. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:771–778Google Scholar

20. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler K: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Google Scholar

21. Ewing JA: Detecting alcoholism: the CAGE questionnaire. JAMA 1984; 252:1905–1907Google Scholar

22. Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Catalano R: Gaps in service utilization by Mexican Americans with mental health problems. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:928–934Google Scholar