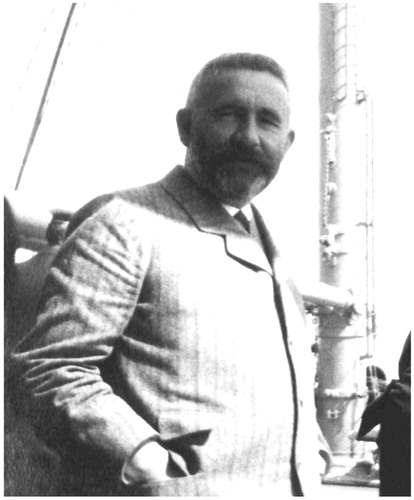

Emil Wilhelm Magnus Georg Kraepelin (1856–1926)

Remembering Emil Kraepelin in 1956, Francis J. Braceland lamented that contemporary neophytes, who brandished the epithet “father of descriptive psychiatry,” threatened to consign Kraepelin’s legacy to the dustbin of history (1). Today, however, on the occasion of his 150th birthday, Kraepelin’s legacy is as vibrant and contested as ever. His distinction between dementia praecox (later schizophrenia) and manic-depressive illness, especially the classification of affective disorders, has come to pervade psychiatric thought and practice.

Kraepelin’s famous nosology evolved in the context of two important developments within German psychiatry in the 1860s and 1870s. On the one hand, it was a reaction to the collapse of the concept of unitary psychosis (i.e., the hypothesis that all psychiatric symptoms were manifestations of one single mental disorder). That hypothesis had been undermined by the clinical studies of Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum and Ewald Hecker, whose descriptions of catatonia and hebephrenia suggested the existence of discrete psychiatric disorders. On the other hand, Kraepelin’s nosology evolved from a critique of cerebral pathologists, such as Theodor Meynert and Paul Flechsig. Kraepelin criticized their efforts to link brain anatomy with clinical symptomatology as speculative and lacking empirical foundation.

In search of alternatives, Kraepelin forged ahead in two directions. First, he turned to Wilhelm Wundt’s experimental psychology to study mental processes. In numerous stimulus reaction experiments, Kraepelin’s early research investigated the effects of exhaustion and various pharmacological stimulants on mental functioning. His aim was to generate quantifiable psychological norms that could be used to diagnose mental deviance. Second, he embarked on clinical research on the long-term course of his patients’ illnesses. He was convinced that careful, longitudinal documentation would enable him to delineate specific disease entities. He began systematically to collect and catalog hundreds of patient histories, developing elaborate research strategies and diagnostic instruments, such as his famous diagnostic cards ( Zählkarten ). On the basis of this clinical research, Kraepelin crafted a nosology that reshaped 20th-century psychiatry (2, 3).

The pervasive influence of his nosology is attributable not simply to the validity of its categories; indeed, Kraepelin himself expected the advance of science to overtake them (2). Rather, it is also an outgrowth of his effectiveness as a teacher and administrator. An entire generation of students was influenced by his textbook—which saw eight editions published in his lifetime—and by his conviction that effective psychiatric care demanded strong institutional support.

Later in his career, Kraepelin’s interests turned to public health issues. A convinced social-Darwinist, he became a fervent advocate of alcoholic abstinence and actively promoted a policy and research agenda in eugenics and racial hygiene (4). He was deeply concerned about the impact of urban life on mental health and was convinced that institutions such as the welfare state and the education system—because they tended to contravene the processes of natural selection—subverted the German people’s biological “struggle for survival” (5). Kraepelin believed that psychiatric science would help to alleviate the deleterious effects of modern civilization. Not least spurred on by the catastrophic human losses of the First World War, he founded the German Research Institute of Psychiatry ( Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Psychiatrie ) in 1917, which in the 1920s became a mecca for psychiatric researchers from around the globe.

1. Braceland FJ: Kraepelin, his system and his influence. Am J Psychiatry 1957; 113:871–876Google Scholar

2. Burgmair W, Engstrom EJ, Weber MM: Emil Kraepelin (vols. 1-6). Munich, Belleville, 2000-2006Google Scholar

3. Decker HS: The psychiatric world of Emil Kraepelin: a many-faceted story of modern medicine. J Hist Neurosci 2004; 13:248–276Google Scholar

4. Kraepelin E: Zur Entartungsfrage. Zentralblatt für Nervenheilkunde und Psychiatrie 1908; 31(Neue Folge 19):745–751Google Scholar

5. Engstrom EJ, Burgmair W, Weber MM: Emil Kraepelin’s “Self-assessment”: clinical autography in historical context. Hist Psychiatry 2002; 13:89–119Google Scholar