Psychiatric Disorders in Young Adult Intercountry Adoptees: An Epidemiological Study

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The prevalences of psychiatric disorders in young adult intercountry adoptees and nonadopted young adults from the general population were compared. METHOD: In the Netherlands, a total of 1,484 young adult intercountry adoptees (72.5% of the original sample at age 10–15 years) and 695 nonadopted subjects (78.1% of the original sample) of comparable age from the general population were interviewed by using a standardized psychiatric interview generating DSM-IV diagnoses. RESULTS: The adopted young adults were 1.52 times as likely to meet the criteria for an anxiety disorder as the nonadopted young adults; the 95% confidence interval (CI) was 1.15–2.00. The adoptees were 2.05 (95% CI=1.32–3.17) times as likely to meet the criteria for substance abuse or dependence. The adopted men were 3.76 (95% CI=1.69–8.37) times as likely to have a mood disorder as nonadopted men, while for women there was no significant difference between adoptees and nonadoptees. No significant difference for the diagnosis of disruptive disorder was found. For all diagnoses together, adoptees with low and middle parental socioeconomic status in childhood did not differ from the comparison subjects, while adoptees with high parental socioeconomic status were 2.17 times (95% CI=1.50–3.13) as likely to meet the criteria for a disorder as nonadoptees with high parental socioeconomic status. CONCLUSIONS: Intercountry adoptees run a higher risk of having severe mental health problems in adulthood than nonadoptees of the same age. The risk of later malfunctioning differs for different disorders and different groups of adoptees.

Worldwide around 30,000 children a year are internationally adopted by nonrelatives (1). The Netherlands is one of the countries with a high number of intercountry adoptees in relation to its total population and to its number of births. The adoption ratio (number of adoptions per 1,000 live births) in the Netherlands, 4.6, is similar to that in the United States, 4.2 (1). In 2001, 1,122 foreign-born children were adopted by Dutch parents (2). In total, the country has around 28,000 intercountry adoptees, mainly from Asia and Latin America.

Our earlier reports showed that internationally adopted children ages 10 to 15 years were at higher risk for showing behavioral or emotional problems than children of the same age from the general population (3, 4). These problems were found to increase across a 3-year follow-up period (5). This study of 2,148 internationally adopted children and adolescents is the only study we know of that compared the longitudinal course of behavioral and emotional problems in a large, representative sample of adopted children and adolescents with that in nonadopted children and adolescents by using similar assessment procedures across time and across samples.

The first generation of intercountry adoptees in the Netherlands has now entered adulthood. Given the increase in problems from early to late adolescence that we found in our earlier studies, we were especially interested in the adaptation of intercountry adoptees in adult life. Most studies have focused on children and adolescents and not on young adults. Furthermore, most existing studies pertained to psychological well-being. To our knowledge, only three, Swedish, studies (6–8) have focused on the mental health of groups of intercountry adoptees that included young adults. The studies of Hjern, Lindblad, and Vinnerljung (6, 7) used data from national registers, including a register based on clinical records from all Swedish hospitals. The authors concluded that international adoptees in Sweden were at higher risk for severe mental health problems than nonadoptees. A limitation of these studies was that diagnostic data were obtained from clinicians who used unstandardized diagnostic procedures. Another limitation was that the authors had information only on adoptees who had been admitted to a hospital, thus ignoring mental health problems in those who did not receive psychiatric care. In another Swedish study, Cederblad et al. (8) found that international adoptees had good mental health and did not differ much from nonadopted individuals. However, the conclusions of this study are limited because of the small and highly selected sample.

In the present study, we used the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (9) to compare the 12-month prevalence of DSM-IV diagnoses in a sample of 1,521 young adult intercountry adoptees with the prevalence in a general population sample. The main aims of the present study were 1) to compare the prevalences of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders in young adult intercountry adoptees and nonadopted young adults and 2) to determine to what extent sex, age, and socioeconomic status are related to the probability of having psychiatric disorders.

Method

Sample and Procedure

Adoption sample

The sample consisted of all children (N=3,519) legally adopted by nonrelatives in the Netherlands and born outside the Netherlands between Jan. 1, 1972, and Dec. 31, 1975. Children were selected from the central adoption register of the Dutch Ministry of Justice, which keeps the records of all children adopted by Dutch parents. Of the 3,309 parents reached, 2,148 participated in the study (64.9%). The adopted children were between the ages of 10 and 15 years. After the first measurement in 1986, the sample was approached again in 1989–1990 for the second measurement. For details on the initial sampling procedure, see our earlier report (3).

During October 1999 and April 2002, with a mean follow-up interval of 13.9 years, we sought contact with all subjects in the original sample of 2,148 except 15 who had died, 13 who were mentally retarded, 72 who had emigrated, 100 who had requested at previous stages to be removed from the sample, 59 who were untraceable, and four for whom we were uncertain that they had been informed of the fact that they had been adopted. Of the approached subjects, 1,521 participated in the study, 288 refused to participate, and 76 did not respond. Thus, the response rate was 74.3% of the time 1 sample (corrected for deceased subjects, mentally retarded individuals, and subjects who had emigrated). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects after the procedure had been fully explained.

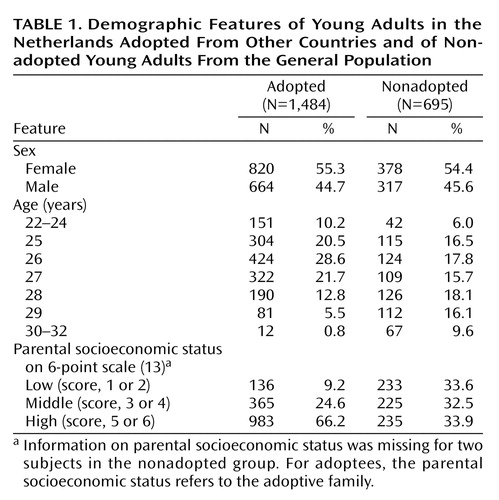

In this study we focused on psychiatric diagnoses obtained through home interviews. Of the 1,521 subjects, 1,484 provided information complete enough for DSM-IV diagnoses, 24 refused to be interviewed, and 13 interviews were lost because of technical problems. Table 1 gives the main demographic features of this sample.

General population sample

For comparison with the adoption sample we used data for a 1983 general population sample from the province of Zuid-Holland, which encompasses more than 3,000,000 people in environments ranging from urban to rural. From municipal registers that list all residents, 100 children of Dutch nationality and of each sex at each age from 4 to 16 years (total N=2,600) were randomly selected. Of the 2,447 parents reached, 2,076 (84.8%) provided usable information. After the first measurement, the sample was approached again in 1985 (time 2), 1987 (time 3), 1989 (time 4), 1991 (time 5), and 1997 (time 6). For details of the initial sampling and data collection procedure, see our previous description (10).

In a previous comparison of adopted and nonadopted subjects, all 10–15-year-olds (N=933) among the 2,076 subjects from the general population sample in 1983 were selected for comparison with the adoption sample in 1986 (3). For the present study we selected the same comparison group from the time 6 sample (1997) (11). Usable DSM-IV information was provided by 695 subjects. They comprised 78.1% of the original comparison group (corrected for deceased individuals, subjects with a mental handicap, and subjects who had emigrated). The mean follow-up interval for the comparison group was 14.7 years. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of this subsample.

Attrition

To investigate selective attrition in the adopted and nonadopted groups, we compared the “dropouts” (i.e., all subjects for whom complete DSM-IV information was not obtained except for those who had died, were mentally retarded, or had emigrated) and the “completers” in both groups with respect to sex, age at time 1, emotional and behavioral problems at time 1, and their parents’ socioeconomic status at time 1. Emotional and behavioral problems were assessed with the Child Behavior Checklist (12). This is a questionnaire in which parents report on 118 specific problem items. A total problems score is computed by summing the scores for each of the 118 problem items. Socioeconomic status was assessed by using a 6-point scale of parental occupation (13), with 1 indicating the lowest socioeconomic status.

Significantly more women than men participated in the follow-up of the adopted and nonadopted groups. In the adopted group 76.7% of the women participated and 67.8% of the men participated (χ2=20.21, df=1, p<0.001); in the nonadopted group 79.6% and 69.1% participated, respectively (χ2=13.46, df=1, p<0.001). The dropouts and completers did not differ significantly in age at time 1 in the adopted group (mean=12.38 years, SD=1.78, versus 12.35, SD=1.64) (t=0.49, df=2046, p=0.62) or the nonadopted group (mean=12.54, SD=1.67, versus 12.40, SD=1.69) (t=1.05, df=931, p=0.29). They also did not differ significantly in socioeconomic status in the adopted group (mean=4.55, SD=1.43, versus 4.63, SD=1.39) (t=–1.11, df=2046, p=0.27) or the nonadopted group (mean=3.46, SD=1.54, versus 3.56, SD=1.56) (t=–0.88, df=927, p=0.39). However, in the adopted group the mean Child Behavior Checklist total problems score at time 1 was significantly higher for the dropouts than that for the completers (mean=25.42, SD=23.49, versus 20.15, SD=18.66) (t=4.78, df=845.41, p<0.001), while in the nonadopted group there was no significant difference (mean=20.07, SD=16.82, versus 19.37, SD=16.36) (t=0.56, df=931, p=0.58). Therefore, it may be concluded that in the present longitudinal study, there was a slight underrepresentation of young adults with more problems at initial assessment in the adopted group.

Instruments

The computerized version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (9) and three sections of the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (14) were used to obtain diagnoses of mental disorders in the 12 months before the interview. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview has more than 300 questions chosen to cover the criteria for DSM-IV diagnoses. Good reliability and validity have been reported (15). Because information concerning disruptive disorders in adulthood is lacking in the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, sections of the DIS covering these disorders were administered after completion of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Each assessment was conducted by an interviewer trained by the Dutch World Health Organization training center for the Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

Statistical Analyses

Logistic regression analyses were used to predict DSM-IV diagnoses from adoption status (nonadopted=0, adopted=1), controlled for sex (male=0, female=1), age (as a continuous variable; in accordance with the Box-Tidwell transformation test, age was scaled as a linear effect), and parental socioeconomic status at time 1 (as a categorical variable: low, middle, or high) to account for differences in sex, age and socioeconomic status distribution between the groups. For each group of diagnoses, we first tested the models for the presence of interactions of adoption status with sex, age, and socioeconomic status. After removal of nonsignificant interactions (p>0.05), main effects that were not part of a significant interaction were tested. For interpretation of the effects, odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed. Odds ratios will be interpreted with the phrase “x times as likely,” and this refers to the fact that the odds of having the diagnosis are x times as high for one group as for the other, not that the probability of having the diagnosis is x times as great. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test showed a good fit for all models. For the adoptees, we also examined the effect of age at placement on the likelihood of a diagnosis; no significant effect was found.

Results

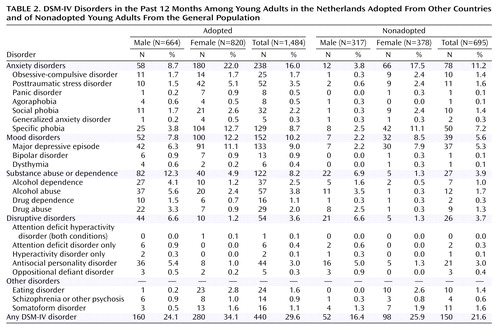

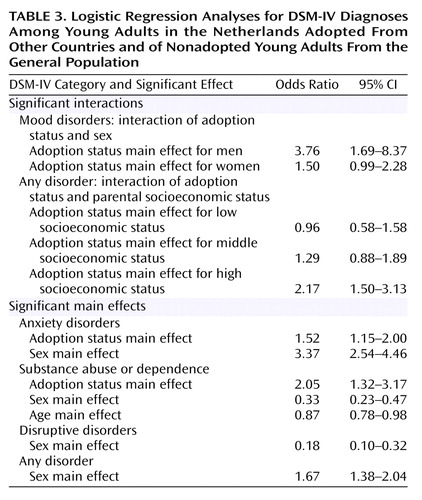

Table 2 shows the percentages of adopted and nonadopted subjects with specific DSM-IV diagnoses. Because the cell sizes were small for the majority of diagnoses, we combined specific disorders into four main groups, based on the classification of DSM-IV. Table 3 shows results of the logistic regression analyses. For each diagnosis, significant effects are shown. For significant interaction effects, separate odds ratios for the effect of adoption status in each subgroup are given.

In the adopted group, 16.0% had at least one anxiety disorder, compared with 11.2% in the nonadopted group. Adopted young adults were 1.52 times as likely to meet the criteria for an anxiety disorder as nonadopted young adults were. Furthermore, women in both groups were 3.37 times as likely to meet the criteria for an anxiety disorder as were men.

For mood disorders, the interaction between adoption status and sex was significant. Therefore, separate odds ratios for the adoption status effect for men and women are given. Adopted men were 3.76 times as likely to have a mood disorder as were nonadopted men, while for women there was no significant difference between adoptees and nonadoptees. Nevertheless, in both groups women were more likely to have a mood disorder than men were; in the adopted group the odds ratio was 1.64 (95% CI=1.16–2.33), and in the nonadopted group it was 4.17 (95% CI=1.79–9.09).

The odds ratio for substance dependence or abuse indicated that the likelihood of having such a disorder was 2.05 times as high in the adoption group as in the general population. We also found that men and younger subjects were more likely than women and older subjects to meet the criteria for substance dependence or abuse.

No significant difference for the diagnosis of disruptive disorder was found between adoptees and nonadoptees. In both groups men were much more likely to meet the criteria for a disruptive disorder than were women.

We also examined all diagnoses together. Subjects with at least one diagnosis were included in the diagnostic category “any disorder.” While adoptees with low and middle parental socioeconomic status in childhood did not differ from the comparison subjects in the general population, adoptees with high parental socioeconomic status were 2.17 times as likely to meet the criteria for a disorder than nonadoptees with high parental socioeconomic status. In the adoption group, the probability of having a psychiatric disorder increased with higher socioeconomic status—low, 22.8%; middle, 29.3%; high, 30.7%—while in the general population the probability decreased—low, 24.5%; middle, 23.6%; high, 17.0%. However, these trends did not reach significance for the adopted subjects (χ2=2.98, df=1, p=0.09) or the nonadopted subjects (χ2>=3.82, df=1, p=0.051).

To investigate whether comorbidity was more common in the adoptees than in the nonadoptees, we took into account the number of diagnoses per subject (from different groups of diagnoses). In the adopted group 28.5% had more than one diagnosis, compared with 20.3% in the general population. However, the difference between the two groups was not significant (χ2=3.59, df=1, p=0.06).

Discussion

Young adult intercountry adoptees were one and a half to nearly four times as likely to show serious mental health problems, especially anxiety and mood disorders and substance abuse and dependence, as were nonadoptees of the same age. The risk varied by diagnostic group, sex, socioeconomic status, and age. The largest risks were for anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and substance abuse and dependence. These findings are consistent with those by Hjern et al. (6), who reported that intercountry adoptees were more likely than nonadoptees to show serious mental health problems; the odds ratios were 3.2 (95% CI=2.9–3.6) for hospital admittance for a psychiatric disorder, 5.2 (95% CI=2.9–9.3) for drug abuse, and 2.6 (95% CI=2.0–3.3) for alcohol abuse. Our study differed from that of Hjern et al. in the design of the adoption cohort and the use of standardized psychiatric interviews.

Contrary to our findings when the sample was much younger (ages 14 to 18 years), in the present study the adoptees did not run a greater risk for meeting the criteria for a disruptive disorder. The 12-month prevalences for antisocial personality disorder were 5.4% for adopted and 5.0% for nonadopted men and 1.0% for adopted and 1.3% for nonadopted women. In adolescence, the adoptees were significantly more likely to have more parent reports and self-reports of delinquent and aggressive behaviors than were nonadopted adolescents of the same age and sex (16). There are a number of possible explanations for this finding. The first is that many antisocial adoptees limited their problematic behavior to adolescence and either discontinued showing psychopathology or changed from one kind of problematic behavior to another form of psychopathology as they grew older. According to Moffitt (17), antisocial behavior can be divided into adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent behavior. It is possible that the higher number of adoptees in adolescence with delinquent and aggressive behaviors reflects only a higher rate of adolescence-limited antisocial behavior. Second, it is possible that adoptees tend to underreport unwanted behaviors to a greater degree than nonadopted individuals. An indication of this tendency can be found in our earlier study, in which adopted adolescents reported less disruptive behavior than was indicated by their parents, whereas in the general population no clear differences between parents’ reports and adolescents’ self-reports of these behaviors were found (16).

Adopted men were much more likely to meet the criteria for a mood disorder than nonadopted men, while for women there was no significant difference between adoptees and nonadoptees in the prevalence of mood disorders. The percentage of adopted men with a mood disorder (7.8%) was not much lower than the percentage of nonadopted women with a mood disorder (8.5%). The female-over-male preponderance in the nonadopted sample (odds ratio=4.17) was much greater than that in the adopted sample (odds ratio=1.64). This suggests that males but not females show greater vulnerability to early negative life experiences or to adoption specifically, resulting in affective problems. A similar trend was found for anxiety disorders, but the effect of the interaction between sex and adoption status on the presence of anxiety disorders was not significant (p=0.10).

In a large sample of intra- and intercountry adolescent adoptees in the United States, Miller et al. (18) also found that adoptive males had less favorable outcomes, compared to the general population, than adoptive females. They found that effect sizes, reflecting differences between adopted and nonadopted individuals, were larger for boys than for girls in regard to substance use, psychological well-being (including emotional distress), and some externalizing behavior.

Sex differences in the occurrence of factors reflecting early adverse experiences, including age at placement in the adoptive family and experiences of neglect or abuse in the child’s country of origin (19), could not explain the sex difference in vulnerability to mood disorders in our study. Males were not more likely to be older at placement (males, mean=27.7 months, SD=23.5; females, mean=29.1 months, SD=24.2) (F=1.13, df=1, 1482, p=0.29), to be neglected (males, 47.1%; females, 46.2%) (χ2=0.07, df=1, p=0.80), or to be abused (males, 13.4%; females, 11.7%) (χ2=0.52, df=1, p=0.47). Although the occurrence of early adverse experiences did not differ between males and females, it might still be possible that the same experiences have different effects on males and females. Because we did not have information on the biological parents of the adopted children, we cannot rule out the possibility that gender differences in the genetic risk for mood disorders in the adoption sample were different from gender differences in genetic risk in the general population sample. This would be the case, for example, if mothers who were depressed were more inclined to abandon their sons than their daughters. However, it is unlikely that this kind of selection is responsible for the large gender difference in the risk for depression among the adoptees. It seems likely that environmental influences associated with adoption played a role in the emergence of mood disorders in males and less so in females. We do not know yet whether preadoption or postadoption experiences or both have had the greatest influence on later functioning.

This greater vulnerability to affective symptoms for adopted males than for females was already present when the subjects in our sample were much younger. In the previous assessment when the subjects were 14 to 18 years old, we also found that the proportions of subjects with high levels of parent-reported and self-reported anxiety and depression were greater for adopted than nonadopted subjects among the boys but not among the girls (16). There is accumulating evidence that childhood depression and adolescent depression have different etiologies, with genetic factors being more important for depression emerging after puberty than for prepubertal depression, and that this is especially so for girls (20). The results of the present study support the notion that we should not base assumptions concerning the mechanisms leading to depression in females on findings from males.

Adoptees with a background of high parental socioeconomic status were more at risk for later psychiatric disorder than were nonadopted individuals who had parents with high socioeconomic status, whereas adoptees with low or middle parental socioeconomic status did not differ from their counterparts in the general population. For individual diagnoses this interaction was not significant. For disruptive disorders a nonsignificant trend was found (p=0.10).

In previous research on this sample we found that adopted children from families with lower socioeconomic status showed better academic performance, had fewer school problems, and were more socially competent than adopted children from families with higher socioeconomic status, whereas in the general population we found that children with higher parental socioeconomic status performed better in school and had fewer problems (3). Similar findings have also been reported for social adjustment (6) and school functioning (21).

An explanation for the poorer functioning of adoptees with high socioeconomic status could be that parents with high socioeconomic status put higher demands on their children and have higher expectations of them (22). Westhues and Cohen (23) found that adoptees were less likely than their siblings to report parent satisfaction with their school performance. Chronic feelings of not being able to satisfy parental standards may be an important stress factor influencing the adoptees’ development.

Limitations

The main limitation of the current study is the selective attrition in the sample. The completers had relatively low scores for parent-reported problems at the initial assessment, whereas those who dropped out had relatively high levels of parent-reported problems at the initial assessment. Consequently, it is possible that our results are an underrepresentation of the mental health disorders in young adult adoptees. Another limitation is that the cell sizes for specific DSM-IV disorders were too small to permit analyses on specific disorders. Finally, no data were available for intracountry adoptees in the Netherlands.

Conclusions and Clinical Implications

Although internationally adopted children were found to be at risk for having psychiatric disorders in adulthood, it should be stressed that the majority did not show serious mental health problems. This is surprising, given the adverse circumstances in which the majority of these children lived the first part of their lives (19). For children who did not have a permanent and satisfactory home in their country of origin, intercountry adoption is a good alternative (24).

An important implication of this study is that (prospective) parents of adopted children, as well as clinicians and policy makers, should be aware of the fact that internationally adopted children have a greater risk of developing serious long-term mental health problems than their peers from the general population. The potentially beneficial effects of early recognition and adequate intervention for mental health problems in internationally adopted children need to be investigated.

The finding that adoptees who grow up in families with high socioeconomic status may experience more problems than those whose parents have low or middle socioeconomic status indicates that an environment associated with high parental socioeconomic status does not automatically give adopted children better developmental opportunities than other environments. This result stresses the importance of environmental influences on the development of mental health problems.

Biological and environmental factors in the etiology of depression in female adults need not be the same as biological and environmental factors in the etiology of depression in male adults. The possibility that genetic factors may play a less prominent role in the etiology of depression in male adults than in female adults, together with our finding that males seem more vulnerable to adoption-related environmental influences, opens up interesting perspectives for studying the role of environmental factors in the emergence of depression in males in general.

In interpreting and generalizing the results of the present study, it is important to realize that changes in adoption practice and postadoption care have taken place in the last few decades. In the 1970s intercountry adoption was a new phenomenon. Most adoptive parents were ill prepared for the problems they would encounter, and adoptees and their families received little support in those early days. At present, in some countries (e.g., Norway and the Netherlands) parents are informed about the increased risks of mental health problems, in addition to other aspects of adoption, in a preparatory course (25). Sometimes special counseling after the child’s arrival is available. Furthermore, in recent decades more information on the possible consequences of intercountry adoption has become available and parents may be less reluctant to seek help for mental health problems in their children. It may be that better preparation of adoptive parents and greater support for adoptees and their families who are in need of help have a positive influence on the development of children who are currently being adopted. Nevertheless, many other aspects of intercountry adoptions, including the placement in a new family, the transition from one country to another, ethnic differences, and the often adverse circumstances in the country of origin, may still place adopted children today at risk for serious mental health problems.

|

|

|

Received Oct. 30, 2003; revision received March 8, 2004; accepted May 3, 2004. From the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Sophia Children’s Hospital, Erasmus MC-University Medical Center Rotterdam. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Ms. Tieman, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Sophia Children’s Hospital, Erasmus MC-University Medical Center Rotterdam, P.O. Box 2060, 3000 CB Rotterdam, the Netherlands; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a grant from the Dutch Ministry of Justice (OE-404/1.98). The authors thank Marijke B. Hofstra, M.D., for her work on the data collection for the general population sample at time 6.

1. Selman P: Intercountry adoption in the new millennium: the “quiet migration” revisited. Popul Res Policy Rev 2002; 21:205–225Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Statistische gegevens betreffende de opneming in gezinnen in Nederland van buitenlandse adoptiekinderen in de jaren 1997–2001 (Statistical numbers concerning the placement of intercountry adopted children in families in the Netherlands between 1997 and 2001). The Hague, Ministry of Justice, 2002Google Scholar

3. Verhulst FC, Althaus M, Versluis-den Bieman HJ: Problem behavior in international adoptees, I: an epidemiological study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1990; 29:94–103Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Verhulst FC, Althaus M, Versluis-den Bieman HJ: Problem behavior in international adoptees, II: age at placement. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1990; 29:104–111Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Verhulst FC, Versluis-den Bieman HJ: Developmental course of problem behaviors in adolescent adoptees. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995; 34:151–159Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Hjern A, Lindblad F, Vinnerljung B: Suicide, psychiatric illness, and social maladjustment in intercountry adoptees in Sweden: a cohort study. Lancet 2002; 360:443–448Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Lindblad F, Hjern A, Vinnerljung B: Intercountry adopted children as young adults—a Swedish cohort study. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2003; 73:190–202Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Cederblad M, Höök B, Irhammar M, Mercke AM: Mental health in international adoptees as teenagers and young adults: an epidemiological study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1999; 40:1239–1248Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. World Health Organization: Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), core version 1.1. Geneva, WHO, 1993Google Scholar

10. Verhulst FC, Akkerhuis GW, Althaus M: Mental health in Dutch children, I: a cross-cultural comparison. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1985; 323:1–108Medline, Google Scholar

11. Hofstra MB, Van der Ende J, Verhulst FC: Continuity and change of psychopathology from childhood into adulthood: a 14-year follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000; 39:850–858Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Achenbach TM: Manual for the Teachers Report Form and 1991 Profile. Burlington, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1991Google Scholar

13. Van Westerlaak JH, Kropman JA, Collaris JWM: Beroepenklapper (Manual for occupational level). Nijmegen, the Netherlands, Institute for Applied Sociology, 1975Google Scholar

14. Robins LN, Cottler L, Bucholtz K, Compton W: National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule, version IV (DIS-IV). St Louis, Washington University, Department of Psychiatry, 1997Google Scholar

15. Andrews G, Peters L: The psychometric properties of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998; 33:80–88Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Versluis-den Bieman HJ, Verhulst FC: Self-reported and parent reported problems in adolescent international adoptees. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1995; 36:1411–1428Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Moffitt TE: Adolescence-limited and life-course persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev 1993; 100:674–701Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Miller BC, Fan X, Christensen M, Grotevant HD, van Dulmen M: Comparisons of adopted and nonadopted adolescents in a large, nationally representative sample. Child Dev 2000; 71:1458–1473; correction, 2003; 74:965Google Scholar

19. Verhulst FC, Althaus M, Versluis-den Bieman HJ: Damaging backgrounds: later adjustment of international adoptees. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31:518–524Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Rutter M: Commentary: nature-nurture interplay in emotional disorders (editorial). J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2003; 44:934–944Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Bohman M: A study of adopted children, their back-ground, environment and adjustment. Acta Paediatr Scand 1972; 61:90–97Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Sparkes J: Schools, Education and Social Exclusion. London, Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, 1999Google Scholar

23. Westhues A, Cohen JS: A comparison of the adjustment of adolescent and young adult inter-country adoptees and their siblings. Int J Behav Dev 1997; 20:47–65Google Scholar

24. Tizard B: Intercountry adoption: a review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1991; 32:743–756Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Sætersdal B, Dalen M: Identity formation in a homogeneous country: intercountry adoption in Norway, in Intercountry Adoption: Development, Trends and Perspectives. Edited by Selman P. London, British Association for Adoption and Fostering, 2000, pp 164–179Google Scholar