Adverse Outcomes Associated With Personality Disorder Not Otherwise Specified in a Community Sample

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors investigated 1) whether adolescents and adults in the community diagnosed with personality disorder not otherwise specified are at elevated risk for adverse outcomes, and 2) whether this elevation in risk is comparable with that associated with the DSM-IV cluster A, B, and C personality disorders. METHOD: A community-based sample of 693 mothers and their offspring were interviewed during the offspring’s childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood. Offspring psychopathology, aggressive behavior, educational and interpersonal difficulties, and suicidal behavior were assessed. RESULTS: Individuals who met DSM-IV criteria for personality disorder not otherwise specified were significantly more likely than those without personality disorders to have concurrent axis I disorders and behavioral, educational, or interpersonal problems during adolescence and early adulthood. In addition, adolescents with personality disorder not otherwise specified were at significantly elevated risk for subsequent educational failure, numerous interpersonal difficulties, psychiatric disorders, and serious acts of physical aggression by early adulthood. Adolescents with personality disorder not otherwise specified were as likely to have these adverse outcomes as those with cluster A, B, or C personality disorders or those with axis I disorders. CONCLUSIONS: Adolescents and young adults in the general population diagnosed with personality disorder not otherwise specified may be as likely as those with DSM-IV cluster A, B, or C personality disorders to have axis I psychopathology and to have behavioral, educational, or interpersonal problems that are not attributable to co-occurring psychiatric disorders. Individuals with personality disorder not otherwise specified and individuals with DSM-IV cluster A, B, or C personality disorders are likely to be at substantially elevated risk for a wide range of adverse outcomes.

Personality disorders are relatively common in the general population. Personality disorder prevalence estimates, based on DSM-III, DSM-III-R, and DSM-IV criteria for specific personality disorders, have ranged from approximately 7% to 15% of the adult population, depending on the diagnostic procedure and the range of personality disorders assessed (1–5). Among adolescents and adults, personality disorders have been found to be associated with 1) impairment and distress not attributable to co-occurring axis I disorders and 2) elevated risk for poor outcomes after accounting for co-occurring axis I disorders (6–12). Previous research (13) has indicated that most personality disorders can be treated effectively with psychotherapy, although there is considerable variability in the methodological rigor, sample size, and scope of the studies that have investigated the effectiveness of psychotherapy for personality disorders (e.g., many individuals require extensive treatment and some personality disorders, such as antisocial personality disorder, may be particularly difficult to treat effectively due in part to the lack of insight and motivation to change that tends to be present among many individuals with antisocial personality disorder). In any event, increased recognition and treatment of personality disorders is likely to have beneficial consequences for many persons with these disorders.

Given such findings, it is of considerable interest that an important category of personality disorders, referred to in DSM-IV as personality disorder not otherwise specified, has thus far been investigated by few epidemiological studies. According to DSM-IV-TR, individuals are appropriately diagnosed with personality disorder not otherwise specified if there is a disorder of personality functioning that does not meet the criteria for a cluster A, B, or C personality disorder. Research has indicated that personality disorder not otherwise specified may be the most common personality disorder diagnosis in many clinical settings (14–18) and that it may be as prevalent as many common axis I disorders (19). However, the high prevalence of personality disorder not otherwise specified may be partially attributable to the fact that comprehensive diagnostic assessments are not conducted in some clinical settings. Most of the epidemiological studies that have assessed personality disorders have not provided findings regarding the prevalence of personality disorder not otherwise specified, and little is currently known about characteristics associated with personality disorder not otherwise specified in the general population. One reason for the lack of systematic population-based research is that there is not yet a clear scientific consensus regarding how to identify individuals with personality disorder not otherwise specified.

In order for large-scale studies to investigate personality disorder not otherwise specified in a systematic manner, and in order for the findings of these studies to be compared and evaluated, it is necessary to develop an operational definition that can be utilized with any validated personality disorder assessment instrument. One way to develop diagnostic criteria that can be implemented with data from any systematic assessment of personality disorder features is to define, in a precise and operational manner, the two examples of personality disorder not otherwise specified set forth in DSM-IV-TR. Accordingly, when the criteria for a cluster A, B, or C personality disorder are not met, personality disorder not otherwise specified may be diagnosed if 1) there are personality disorder features that come within one diagnostic criterion of meeting DSM-IV thresholds for two or more personality disorders (e.g., four borderline personality disorder features and four schizotypal personality disorder features), or 2) diagnostic criteria are met for depressive or passive-aggressive personality disorder. Further research may determine that the definition should be expanded by diagnosing personality disorder not otherwise specified when the total number of personality disorder features exceeds a specified threshold. However, while this kind of threshold has been used in some studies (20), a clear consensus about the threshold that should be used will require further investigation. It is also important to investigate the characteristics of personality disorder not otherwise specified that are operationally defined based on the information and examples in DSM-IV-TR. Our review of the literature indicates that the present study is the first community-based longitudinal investigation to examine mental health outcomes associated with personality disorder not otherwise specified (1–5).

Method

Subjects and Procedure

Nine hundred seventy-six mothers of children between the ages of 1 and 10 (mean age=5.5 years, SD=2.8) were randomly sampled on the basis of residence in Albany and Saratoga Counties in the State of New York and interviewed in 1975 (21). These mothers and a randomly sampled child were interviewed in 1983 (N=778, mean offspring age=13.7 [SD=2.8]), 1985–1986 (N=776, mean offspring age=16.3 [SD=2.8]), and 1991–1993 (N=749, mean offspring age=22.1 [SD=2.7]). These families were demographically representative of families in the sampled region (22). The findings in the present report are based on data from 693 families that were interviewed during the offspring’s adolescence and early adulthood. These families did not differ from the remainder of the baseline sample with regard to the prevalence of maternal or offspring behavioral or emotional problems; paternal substance abuse was less prevalent. The study procedures have been approved by the Columbia University and New York State Psychiatric Institute institutional review boards. Written informed consent or assent was obtained from all participants after the interview procedures were fully explained. The mothers and offspring were interviewed separately by extensively trained and supervised lay interviewers. Additional information regarding the methodology is available from previous reports (21–23) and on the study web site (http://nyspi.org/childcom).

A stratified random sampling procedure was used in 1975 to obtain a representative sample of families living in Albany and Saratoga counties. Census data were used to create primary sampling units for these counties. The primary sampling units were stratified by urban/rural status, ethnicity, and median income. A systematic sample of primary sampling units in each county was then drawn with probability proportional to the number of households and probabilities equal for members of all strata. Households with at least one child between the ages of 1 and 10 years were qualified for the study. Address lists were compiled, and interviewers were sent to the selected addresses. A total of 1,141 families were invited to participate in the study, and 976 families (85.5%) were interviewed in 1975; 724 (74.2%) of these families were reinterviewed in 1983. A supplementary sample of 54 families were randomly sampled from urban poverty areas and interviewed in 1983 to improve the representativeness of the sample. This brought the total families interviewed in 1983 to 778. Seven hundred seventy-six families, comprising 690 (88.7%) of the families interviewed in 1983 and 86 families who had been interviewed in 1975 but not in 1983, were interviewed in 1985–1986. Seven hundred forty-nine families, comprising 657 (84.4%) of the families interviewed in 1983 and 92 families who had been interviewed in 1975 but not in 1983, were interviewed in 1991–1993.

Assessment of Psychiatric Disorders

The parent and youth versions of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (24) were administered during the childhood and adolescence of the offspring to assess anxiety (agoraphobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, and separation anxiety disorder), disruptive disorders (attention deficit, conduct, and oppositional defiant disorders), eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa), mood disorders (dysthymic and major depressive disorders), and substance use disorders (alcohol and drug abuse/dependence). An age-appropriate version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children was administered to the offspring during early adulthood. The reliability and validity of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children as employed in this study are comparable to those of other structured interviews (25).

Interview items used to assess personality disorders were drawn from the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire (26), the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (27), the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, and the Disorganizing Poverty Interview (21). Items were originally selected on the basis of correspondence with DSM-III-R criteria and combined using algorithms developed by consensus among one psychiatrist and two clinical psychologists (8). Following the publication of DSM-IV, items from the study protocol that had been administered were added to the algorithms to maximize correspondence with DSM-IV, most notably to assess depressive personality disorder.

Thirty-one maternal interview items and 116 offspring interview items assessed DSM-IV personality disorder criteria (i.e., “personality disorder symptoms”). Ratings of the behavior and appearance of the study offspring (five items) were completed by the interviewers. Personality disorder symptoms were considered present if reported by any informant. Cluster A, B, C, depressive, and passive-aggressive personality disorders were identified as present if DSM-IV criteria thresholds were met during early adulthood. However, because personality disorder symptoms must be persistent in order for an adolescent to be diagnosed with a personality disorder, cluster A, B, C, depressive, and passive-aggressive personality disorders were only diagnosed during adolescence if DSM-IV criteria were met during both adolescent assessments or if the criteria were met at one assessment and the personality disorder symptom level was within one criterion of the diagnosis at the other assessment. In accordance with DSM-IV criteria, antisocial personality disorder was assessed among individuals with a history of conduct disorder who were ≥18 years of age. Consistent with DSM-IV criteria, personality disorder not otherwise specified was identified as being present (among individuals who did not have cluster A, B, or C personality disorders) if the number of personality disorder criteria identified as being present came within one criterion of meeting the threshold for two or more specific personality disorders or if criteria were met for depressive personality disorder or passive-aggressive personality disorder.

Research has supported the reliability and validity of the items and algorithms used to assess personality disorders. Personality disorder symptoms, assessed by using these items and algorithms, were moderately stable during adolescence and early adulthood, and the stability of personality disorder symptoms was similar to the stability of personality disorder symptoms in adult studies that have used similar test-retest intervals (23). Personality disorder prevalence during adolescence (10.97%) and early adulthood (11.98%) was within the range of prevalence estimates that have been obtained in adult community samples (5). The validity of the items and algorithms was supported by findings indicating that adolescent personality disorders were associated with elevated risk for axis I psychiatric disorders, criminal or violent behavior, and suicidal behavior during early adulthood (6, 7).

Assessment of Educational Achievement, Interpersonal Difficulties, and Aggression

One Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children module assessed educational problems: attention difficulties, failure to complete homework, lack of interest in schoolwork, negative attitudes about school, and poor teacher evaluations. Poor educational achievement was considered present if the individual failed to complete secondary school by age 18 or if he or she was ≥1 year behind his or her peers in school. Another Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children module assessed acts of physical aggression. The following interpersonal difficulties were assessed during the maternal and offspring interviews: cruelty toward peers, difficulty making friends, frequent arguments with adults or peers, loneliness and interpersonal isolation, lack of close friends, poor relationships with friends or peers, refusal to share with others, and fights with family members.

Data Analysis

Analyses of contingency tables were conducted to investigate 1) whether individuals with personality disorder not otherwise specified were more likely than those without personality disorders to have concurrent and subsequent axis I psychopathology, interpersonal or educational problems, and suicide attempts during adolescence and early adulthood; and 2) whether individuals with personality disorder not otherwise specified were more or less likely than those with cluster A, B, or C personality disorders to have these outcomes. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine 1) whether the associations between personality disorder status and the dependent variables remained significant when axis I disorders were controlled; and 2) whether personality disorder not otherwise specified was associated with adverse outcomes during early adulthood when the corresponding problem during adolescence was controlled. Separate analyses were conducted with the data from adolescence and early adulthood because personality disorder symptom levels declined from adolescence through early adulthood (23). There was sufficient statistical power to detect an association with a modest effect size, such as a correlation of 0.30.

Results

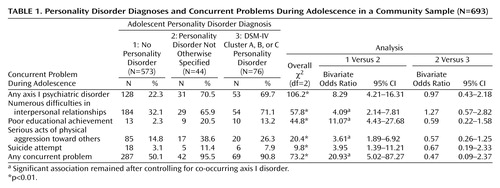

Adolescent Personality Disorders and Concurrent Problems

Forty-four individuals (6.3%) were diagnosed with personality disorder not otherwise specified during adolescence. One individual had depressive personality disorder, five had passive-aggressive personality disorder, and 41 were classified as “mixed” (i.e., within one criterion of meeting the threshold for two or more personality disorders). Three individuals had both passive-aggressive and “mixed” personality disorder. Adolescents with personality disorder not otherwise specified had fewer personality disorder symptoms than did those with cluster A, B, or C personality disorders (t=–3.85, df=118, p<0.001). However, relative to adolescents with no personality disorders, adolescents with personality disorder not otherwise specified were significantly more likely to have concurrent axis I psychopathology, numerous interpersonal difficulties, poor educational achievement, acts of physical aggression, suicide attempts, and any concurrent problem (Table 1). Most of these associations remained significant after axis I disorders were controlled statistically. Individuals with a cluster A, B, or C personality disorder were not significantly more likely than were those with personality disorder not otherwise specified to have any of these problems. Depressive personality disorder, passive-aggressive personality disorder, and mixed personality disorder not otherwise specified were all significantly associated with mental health problems during adolescence and early adulthood.

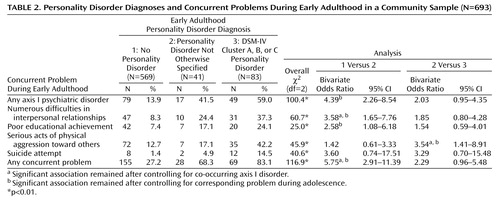

Early Adulthood Personality Disorders and Concurrent Problems

Forty-one individuals (5.9%) were diagnosed with personality disorder not otherwise specified during early adulthood. Three individuals had depressive personality disorder, 10 had passive-aggressive personality disorder, and 30 had “mixed” personality disorder not otherwise specified (one of these 30 individuals had depressive personality disorder, and one had passive-aggressive personality disorder). The young adults with personality disorder not otherwise specified had fewer personality disorder symptoms than did those with cluster A, B, or C personality disorders (t=–2.19, df=122, p=0.03). However, relative to those with no personality disorders, young adults with personality disorder not otherwise specified were significantly more likely to have concurrent axis I psychopathology, numerous difficulties in interpersonal relationships, poor educational achievement, and any concurrent problem (Table 2). Several of these associations remained significant after we controlled statistically for corresponding problems during adolescence. The associations with interpersonal difficulties and any concurrent problem remained significant after we controlled statistically for co-occurring axis I disorders. Young adults with cluster A, B, or C personality disorders were significantly more likely than young adults with personality disorder not otherwise specified to report serious acts of physical aggression during early adulthood. This association remained significant after we controlled for acts of physical aggression during adolescence and co-occurring axis I disorders.

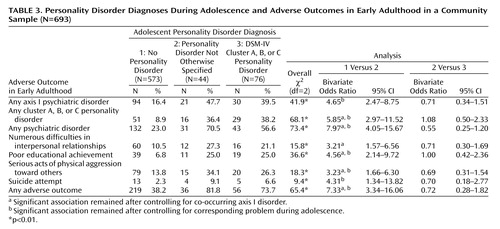

Adolescent Personality Disorders and Subsequent Outcomes

Adolescents with personality disorder not otherwise specified were significantly more likely than those without personality disorders to have axis I disorders; cluster A, B, or C personality disorders; any psychiatric disorder; numerous interpersonal difficulties; poor educational achievement; serious acts of physical aggression toward others; suicide attempts; and any adverse outcome during early adulthood (Table 3). Several of these associations remained significant after we controlled statistically for corresponding problems during adolescence. The associations with personality disorders, any psychiatric disorder, interpersonal difficulties, poor educational achievement, physical aggression, and any adverse outcome during early adulthood remained significant after we controlled statistically for co-occurring axis I disorders. Early adulthood personality disorder symptoms mediated each of these associations. Adolescents with cluster A, B, or C personality disorders were not more likely than those with personality disorder not otherwise specified to have any of these outcomes during early adulthood. Depressive personality disorder, passive-aggressive personality disorder, and mixed personality disorder not otherwise specified during adolescence were all significantly associated with adverse outcomes.

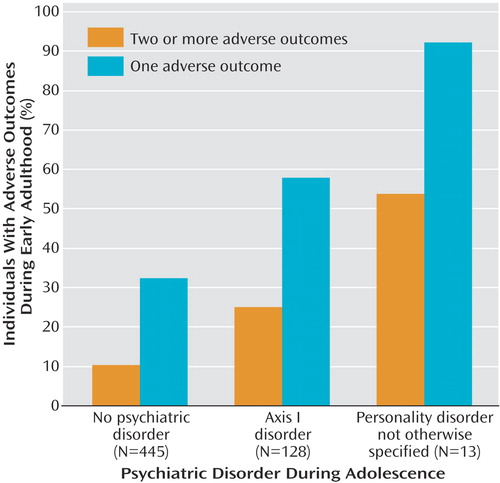

As seen in Figure 1, there were significant differences in likelihood of experiencing adverse outcomes by early adulthood among adolescents with personality disorder not otherwise specified alone (i.e., no co-occurring axis I disorder [N=13]), adolescents with axis I psychopathology but no personality disorder (N=128), and those with no psychiatric disorder (N=445). The likelihood of experiencing any adverse outcome was significantly higher, relative to those with no psychiatric disorder, among those with personality disorder not otherwise specified (odds ratio=25.08, CI=3.23–194.77) and those with an axis I disorder (odds ratio=2.86, CI=1.91–4.29). The likelihood was also significantly higher for those with personality disorder not otherwise specified relative to those with an axis I disorder (odds ratio=8.76, CI=1.11–69.39). In addition, the likelihood of experiencing two or more adverse outcomes was significantly higher, relative to those with no psychiatric disorder, among those with personality disorder not otherwise specified (odds ratio=10.12, CI=3.26–31.40) and those with an axis I disorder (odds ratio=2.89, CI=1.75–4.78). The likelihood was also significantly higher for those with personality disorder not otherwise specified relative to those with an axis I disorder (odds ratio=3.50, CI=1.10–11.18).

Discussion

The present findings suggest that individuals in the general population who meet DSM-IV criteria for personality disorder not otherwise specified may be as likely as individuals with cluster A, B, or C personality disorders to experience adverse outcomes—including axis I disorders—and behavioral, educational, or interpersonal difficulties. Our findings suggest that elevated risk for adverse outcomes among adolescents with personality disorder not otherwise specified is not likely to be attributable to co-occurring axis I psychopathology or to preexisting behavioral, educational, or interpersonal difficulties. The present findings also suggest that individuals with personality disorder not otherwise specified may be more likely than individuals with anxiety, depressive, disruptive, or substance use disorders to experience adverse outcomes. Our review of the literature indicates that this is the first community-based longitudinal study to examine a wide range of correlates and outcomes of personality disorder not otherwise specified and to compare the risk for poor outcomes between individuals with personality disorder not otherwise specified and those with cluster A, B, or C personality disorders.

In addition, the present findings suggest that when personality disorder symptoms are assessed in a systematic manner in a community-based sample, the prevalence of personality disorder not otherwise specified may be greater than that of any specific personality disorder. Our finding that the prevalence of personality disorder not otherwise specified was approximately 6% during both adolescence and early adulthood indicates that the diagnostic criteria used in the present study can be applied in a consistent and reliable manner. Thus, the present findings are consistent with research indicating that personality disorder not otherwise specified may be the most common personality disorder diagnosis in clinical samples (14–18) and may be as prevalent as many common axis I disorders (19). Our findings, taken together with previous findings, support the inference that personality disorder not otherwise specified is a common, clinically significant condition that is associated with considerable impairment and distress.

On the basis of the present findings, it may be advisable for future population-based studies of personality disorders to assess personality disorder not otherwise specified in a systematic and comprehensive manner. The operational definition of personality disorder not otherwise specified in the present study has the advantage of being based directly on DSM-IV criteria and being readily implemented with currently available personality disorder assessment instruments. It may also be useful to investigate the clinical utility, reliability, and validity of other assessment methods, such as identifying personality disorder not otherwise specified if the total number of personality disorder symptoms meets a specified diagnostic threshold (20). Previous research has shown that personality disorders are associated with adverse outcomes (6–8, 10–12) and that they can be treated effectively (13). Improved recognition and treatment of personality disorders, including personality disorder not otherwise specified, may help many individuals to avoid adverse long-term outcomes.

The limitations of the present study require consideration. Because the participants were adolescents and young adults, further research will be needed in order to determine whether personality disorder not otherwise specified is associated with elevated risk for adverse outcomes among older adults. Future studies will also need to investigate whether individuals with personality disorder not otherwise specified are at elevated risk for outcomes such as occupational and financial difficulties. Although some of the outcomes that were investigated, particularly interpersonal difficulties, are personality disorder characteristics, different interview items were used to assess personality disorder traits and adverse outcomes. Thus, the associations of personality disorders with these problems are not attributable to item overlap. Further, individuals with personality disorder not otherwise specified were at elevated risk for adverse outcomes even when we controlled statistically for corresponding problems during adolescence (Table 3). Although personality disorder symptoms were assessed with items from several instruments, research has supported the reliability and validity of these assessment procedures (6, 7, 23). Stratified random sampling procedures were used to maximize the representativeness of the sample, sample retention was within expected parameters, and the prevalence of personality disorder not otherwise specified was approximately 6% during both adolescence and early adulthood, suggesting that sample attrition did not have a systematic effect on the present findings. It will be of interest for future studies to investigate the prevalence and sequelae of personality disorder not otherwise specified in samples that are representative of other regions and age groups.

|

|

|

Received Aug. 5, 2003; revisions received June 20 and July 6, 2004; accepted Sept. 24, 2004. From the Columbia University Department of Psychiatry/New York State Psychiatric Institute; and the Department of Psychiatry, New York University, New York. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Johnson, Box 60, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Dr., New York, NY 10032; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grants MH-36971, MH-38916, and MH-49191 to Dr. Cohen and a National Institute on Drug Abuse grant (DA-03188) to Dr. Brook.

Figure 1. Early Adulthood Adverse Outcomes in a Community Sample by Adolescent Psychiatric Disorder Diagnosis

1. Moldin SO, Rice JP, Erlenmeyer-Kimling L, Squires-Wheeler E: Latent structure of DSM-III-R axis II psychopathology in a normal sample. J Abnorm Psychol 1994; 103:259–266Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Klein DN, Riso LP, Donaldson SK, Schwartz JE, Anderson RL, Ouimette PC, Lizardi H, Aronson TA: Family study of early-onset dysthymia: mood and personality disorders in relatives of outpatients with dysthymia and episodic major depression and normal controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:487–496Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Maier W, Lichtermann D, Klingler T, Heun R, Hallmayer J: Prevalences of personality disorders (DSM-III-R) in the community. J Pers Disord 1992; 6:187–196Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Samuels J, Eaton WW, Bienvenu OJ, Brown CH, Costa PT, Nestadt G: Prevalence and correlates of personality disorders in a community sample. Br J Psychiatry 2002; 180:536–542Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V: The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58:590–596Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Johnson JG, Cohen P, Skodol AE, Oldham JM, Kasen S, Brook J: Personality disorders in adolescence and risk of major mental disorders and suicidality during adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:805–811Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Johnson JG, Cohen P, Smailes E, Kasen S, Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Brook JS: Adolescent personality disorders associated with violence and criminal behavior during adolescence and early adulthood. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:1406–1412Link, Google Scholar

8. Perry JC: Longitudinal studies of personality disorders. J Personal Disord 1993; 7(suppl):63–85Google Scholar

9. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Dyck IR, Stout RL, Bender DS, Grilo CM, Shea MT, Zanarini MC, Morey LC, Sanislow CA, Oldham JM: Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:276–283Link, Google Scholar

10. Brent DA, Johnson BA, Perper J, Connolly J, Bridge J, Bartle S, Rather C: Personality disorder, personality traits, impulsive violence, and completed suicide in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994; 33:1080–1086Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Pilkonis PA, Frank E: Personality pathology in recurrent depression: nature, prevalence, and relationship to treatment response. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:435–441Link, Google Scholar

12. Massion AO, Dyck IR, Shea MT, Phillips KA, Warshaw MG, Keller MB: Personality disorders and time to remission in generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002; 59:434–440Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Perry JC, Banon E, Ianni F: Effectiveness of psychotherapy for personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1312–1321Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Fabrega H, Ulrich R, Pilkonis P, Mezzich J: On the homogeneity of personality disorder clusters. Compr Psychiatry 1991; 32:373–386Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Koenigsberg HW, Kaplan RD, Gilmore MM, Cooper AM: The relationship between syndrome and personality disorder in DSM-III: experience with 2,462 patients. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:207–212Link, Google Scholar

16. Loranger AW: The impact of DSM-III on diagnostic practice in a university hospital. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:672–675Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Morey LC: Personality disorders in DSM-III and DSM-III-R: convergence, coverage, and internal consistency. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:573–577Link, Google Scholar

18. Westen D, Arkowitz-Westen L: Limitations of axis II in diagnosing personality pathology in clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1767–1771Link, Google Scholar

19. Clark LA, Watson D, Reynolds S: Diagnosis and classification of psychopathology: challenges to the current system and future directions. Annu Rev Psychol 1995; 46:121–153Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Loranger AW, Janca A, Sartorius N (eds): Assessment and Diagnosis of Personality Disorders: The ICD-10 International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE). New York, Cambridge University Press, 1997Google Scholar

21. Kogan LS, Smith J, Jenkins S: Ecological validity of indicator data as predictors of survey findings. J Soc Serv Res 1977; 1:117–132Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Cohen P, Cohen J: Life Values and Adolescent Mental Health. Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1996Google Scholar

23. Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Skodol AE, Brook J: Age-related change in personality disorder symptom levels between early adolescence and adulthood: a community-based longitudinal investigation. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 102:265–275Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Costello EJ, Edelbrock CS, Duncan MK, Kalas R: Testing of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) in a Clinical Population: Final Report to the Center for Epidemiological Studies, NIMH. Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh, 1984Google Scholar

25. Cohen P, O’Connor P, Lewis SA, Malachowski B: A comparison of the agreement between DISC and K-SADS-P interviews of an epidemiological sample of children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1987; 26:662–667Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Hyler SE, Rieder RO, Williams JBW, Spitzer RL, Hendler J, Lyons M: The Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire: development and preliminary results. J Personal Disord 1988; 2:229–237Crossref, Google Scholar

27. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II), part I: description. J Personal Disord 1995; 9:83–91Crossref, Google Scholar