Childhood Trauma, Dissociation, and Psychiatric Comorbidity in Patients With Conversion Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The aim of this study was to evaluate dissociative disorder and overall psychiatric comorbidity in patients with conversion disorder. METHOD: Thirty-eight consecutive patients previously diagnosed with conversion disorder were evaluated in two follow-up interviews. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, the Dissociation Questionnaire, the Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire, and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire were administered during the first follow-up interview. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders was conducted in a separate evaluation. RESULTS: At least one psychiatric diagnosis was found in 89.5% of the patients during the follow-up evaluation. Undifferentiated somatoform disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, dysthymic disorder, simple phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, major depression, and dissociative disorder not otherwise specified were the most prevalent psychiatric disorders. A dissociative disorder was seen in 47.4% of the patients. These patients had dysthymic disorder, major depression, somatization disorder, and borderline personality disorder more frequently than the remaining subjects. They also reported childhood emotional and sexual abuse, physical neglect, self-mutilative behavior, and suicide attempts more frequently. CONCLUSIONS: Comorbid dissociative disorder should alert clinicians for a more chronic and severe psychopathology among patients with conversion disorder.

Conversion disorder is linked historically to the concept of hysteria. Toward the end of the 19th century, Pierre Janet conceptualized hysteria as a dissociative disorder and described somatoform symptoms as aspects of this condition in his traumatized patients (1). In the beginning of his career, Janet’s contemporary Sigmund Freud also considered hysteria a trauma-based disorder (2). However, Freud later conceptualized the somatoform symptoms of hysteria as the result of a neurotic defense mechanism and referred to them as conversion symptoms. In DSM-II, the conversion and dissociative types of hysterical neurosis were classified as variants of a single disorder. In DSM-III and its subsequent versions, dissociative disorders have been considered a separate group. On the other hand, the latest version of the International Classification of Diseases, the ICD-10, put all manifestations of hysterical neurosis under the rubric of dissociative disorders. This is in accordance with the findings of modern studies that have resurrected evidence for the relationship between somatoform symptoms and dissociation (3–5).

Both somatoform and psychoform dissociation are correlated with reported childhood trauma (6–9). Of dissociative disorder patients in Turkey, 46.0% reported childhood physical abuse and 33.0% reported childhood sexual abuse (10). High sexual abuse rates have been found among patients with pseudoseizures (11) and somatization disorder (12) and in conversion disorder patients in general (13). Sexual abuse and dissociation are independently associated with several indicators of mental health disturbance, including risk-taking behavior such as suicidality, self-mutilation, and sexual aggression (14).

In Turkey, conversion symptoms are observed both in psychiatric and general medical settings quite frequently. Among outpatients who were admitted to a primary health care institution in a semirural area, the prevalence of conversion symptoms in the preceding month was 27.2% (15). The lifetime rate increased to 48.2%. Patients with conversion disorder have overall psychiatric symptom scores close to those of general psychiatric patients (4), suggesting high psychiatric comorbidity. In a primary health care center, conversion symptoms were more frequently observed among subjects who had an ICD-10 diagnosis; depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and neurasthenia were the most prevalent psychiatric disorders among them (15).

The present study attempted to assess dissociative disorder and overall psychiatric comorbidity in patients with conversion disorder determined during follow-up evaluations. In order to investigate a possible role of dissociation in the overall characteristics of the psychopathology, we also compared conversion disorder patients who had a DSM-IV dissociative disorder with those who did not. Since general psychiatric assessment tools do not include sections that evaluate dissociative disorders, self-rating instruments and a separate diagnostic interview were used for this purpose.

Method

Participants

All patients admitted for the first time to the psychiatric outpatient unit of the Cumhuriyet University Medical Faculty Hospital in Sivas, Turkey, over a 12-month period (Jan. 1 to Dec. 31, 1997) who had a clinical diagnosis of conversion disorder were considered for participation in the follow-up study. Sixty-eight patients had been diagnosed as having conversion disorder during the 1-year study period; 70.6% (N=48) of them had pseudoseizures. Nine (13.2%) patients had paralysis, seven (10.3%) had paresthesia, and two (2.9%) had been unable to speak.

Thirty-eight patients (55.9%) were available for the follow-up interviews. Thirty patients had refused to participate (N=11) or had moved (N=19). Women made up 86.8% (N=33) of those who completed the questionnaires and 86.7% (N=26) of those who did not complete them; this difference was not significant (p>0.05, Fisher’s exact test). Patients who did not participate were slightly older (mean=35.9, SD=13.2) than those who participated (mean=33.3, SD=10.5), but the difference was not significant (t=0.90, df=66, p>0.05).

Among the final study group, 34 patients (89.5%) had pseudoseizures, and four patients (10.5%) had paralysis. They were between 16 and 56 years of age, the average age of the probands was 34.5 years (SD=11.8). The male subjects (mean age=42.2, SD=6.9) were older than the female subjects (mean age=32.0, SD=10.4), but the difference was not significant (t=2.11, df=36, p>0.05). Three patients (7.9%) were below 18 years of age. The patients had a mean of 6.9 years (SD=3.9) of education. The patients who agreed to participate provided written informed consent after the study procedures had been fully explained.

Instruments

| 1. | The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders (SCID-D) is a semistructured interview developed by Steinberg (16). It is used to make DSM-IV diagnoses of all dissociative disorders. The Turkish version of the SCID-D (unpublished 1996 translation by V. Şar et al.) was investigated in a study of 40 patients with a dissociative disorder and 40 control subjects and yielded a 100% agreement for presence and absence of a dissociative disorder (17). Interrater reliability of the interview was evaluated by four psychiatrists using 10 videotaped interviews of patients with either dissociative disorder or other psychiatric disorders. The sole discrepancy between raters was observed on the type of the dissociative disorder in one patient who was assessed as having either dissociative identity disorder or dissociative disorder not otherwise specified. | ||||

| 2. | The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) is a semistructured interview developed by Spitzer and colleagues (18). This widely used interview serves as a diagnostic instrument for DSM-III-R axis I psychiatric disorders. | ||||

| 3. | The posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) module of the SCID (19) basically assesses the DSM criteria. It has a sensitivity of 0.69 and specificity of 1.00 for the diagnosis of PTSD, with an overall interrater agreement of 0.76 (19). | ||||

| 4. | The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II) is a semistructured interview developed by Spitzer and colleagues (20). It serves as a diagnostic instrument for DSM-III-R axis II personality disorders. The section for borderline personality disorder was administered in this study. The Turkish version (21) of this section has a reliability of 0.95 (kappa). | ||||

| 5. | The Dissociation Questionnaire is a 63-item self-report instrument developed by Vanderlinden and colleagues (22). It evaluates the severity of psychological dissociation, with possible scores ranging from 1 to 5. According to a study among Turkish patient groups, the Dissociation Questionnaire differentiates patients with a chronic dissociative disorder from those with other psychiatric disorders (23). At a cutoff score of 2.5, the sensitivity of the scale is 0.85 and the specificity 0.83. It has a test-retest correlation of 0.74 as measured in a group of dissociative disorder patients with a 41-day interval (23). | ||||

| 6. | The Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire is a 20-item self-report instrument that evaluates the severity of somatoform dissociation. The Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire was developed by Nijenhuis and colleagues (5). The Turkish version of the scale has a 1-month test-retest correlation of 0.95. A cutoff point of 35 yielded a sensitivity of 0.84 and a specificity of 0.87 for dissociative disorder diagnosis in a Turkish clinical sample (10). | ||||

| 7. | The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire is a 53-item self-report instrument developed by Bernstein and colleagues (24) that evaluates childhood emotional, physical, and sexual abuse and childhood physical and emotional neglect. Possible scores for each type of childhood trauma range from 1 to 5. The sum of the scores derived from each trauma type provides the total score ranging from 5 to 25. Cronbach’s alpha for the factors related to each trauma type ranges from 0.79 to 0.94, indicating high internal consistency (24). The scale also demonstrated good test-retest reliability over a 2–6-month interval (intraclass correlation=0.88). A separate history form (25) that gathers information about the details of the traumatic experiences, self-mutilative behavior, and suicide attempts was also administered to all patients. The definitions by Walker et al. (26) and by Brown and Anderson (27) for childhood abuse and neglect were used in this history form. | ||||

Procedure

The participants were invited by a phone call to the hospital where they had been evaluated originally for follow-up interviews. Two follow-up interviews were conducted in June 1998 and 1999. The duration between index admission and the first follow-up interview was between 7 and 18 months (mean=14.2 months, SD=4.1). The first follow-up interview consisted of the administration of all the instruments except the SCID-D, which was administered during the second follow-up interview. All interviews at the first step of the study were conducted by the same psychiatrist. The SCID-D interviews were conducted by three psychiatrists. All interviewers had extensive experience in the administration of the instruments.

Results

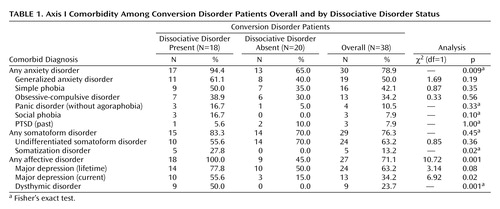

Thirty-four (89.5%) of the patients had at least one axis I psychiatric diagnosis at follow-up. Common diagnoses were undifferentiated somatoform disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, simple phobia, major depression, dysthymic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (Table 1). The mean number of axis I psychiatric diagnoses (including dissociative disorders) was 2.8 (SD=1.7, range=0–7). None of the patients had hypochondriasis, somatoform pain disorder, bipolar affective disorder, psychotic disorder, substance abuse, or an eating disorder.

Thirty-one patients (81.6%) with conversion disorder had a Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire score above 35.0, and 16 patients (42.1%) had a Dissociation Questionnaire score above 2.50. In accordance with these rates above the cutoff scores, 18 patients (47.4%) had a DSM-IV dissociative disorder in the structured diagnostic evaluation. Three of them (7.9%) had dissociative identity disorder. Thirteen patients (34.2%) had dissociative disorder not otherwise specified. Two patients (5.3%) had dissociative amnesia. None of the patients had depersonalization disorder or dissociative fugue solely, i.e., these conditions existed only in context of dissociative identity disorder or dissociative disorder not otherwise specified. Two cases of dissociative disorder not otherwise specified were mild forms of dissociative identity disorder, i.e., they had distinct personality states without fully meeting diagnostic criteria of the latter. The remaining 11 cases of dissociative disorder not otherwise specified predominantly had a combination of dissociative amnesia and depersonalization.

Although patients who had a dissociative disorder were slightly younger (mean=30.9 years, SD=8.7) than those who did not (mean=35.5 years, SD=11.7), this difference was not significant (t=1.35, df=36, p>0.05). Sixteen patients (88.9%) of the dissociative disorder group were female, whereas this rate was 85.0% (N=17) for the nondissociative group (p>0.05, Fisher’s exact test). Subjects with dissociative disorder had current major depression and dysthymic disorder more frequently than the remaining patients. All somatization disorder patients were among them. Half (50.0%) of the conversion subjects had generalized anxiety disorder at follow-up, however, these patients were distributed between the two groups homogenously (Table 1).

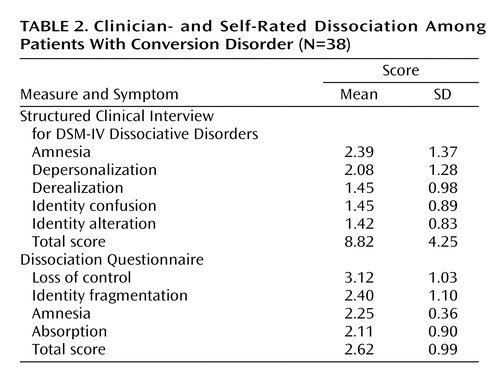

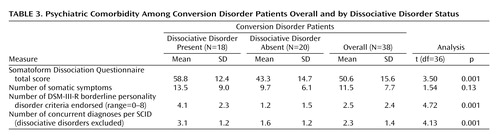

Dissociative amnesia and depersonalization were symptoms with the highest mean score in the objective evaluation that used the SCID-D (Table 2). For self-rated symptoms, loss of control had the highest score. Subjects with dissociative disorder endorsed borderline personality disorder criteria and had concurrent SCID diagnoses more frequently than the remaining patients (Table 3). Nine (23.7%) of the patients were diagnosed as having borderline personality disorder. All but one of the subjects with borderline personality disorder were among patients who had dissociative disorder. This difference was significant (p=0.007, Fisher’s exact test). Two of these patients had dissociative identity disorder and six had dissociative disorder not otherwise specified.

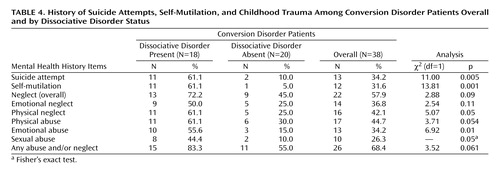

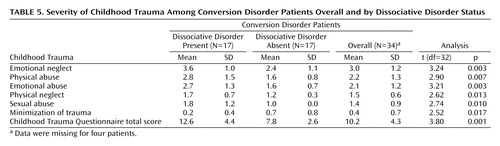

Table 4 shows the frequencies of self-destructive behavior and reported childhood trauma. Patients with dissociative disorder reported suicide attempts, self-mutilative behavior, childhood physical neglect, and childhood emotional and sexual abuse more frequently. The quantitative measures demonstrated that they had significantly high scores for all types of abuse and neglect as well as high total childhood trauma scores (Table 5). Conversion disorder patients without dissociative disorder were more prone to minimize their trauma history. When a stepwise multiple regression analysis was conducted with Dissociation Questionnaire score as the criterion variable and the five childhood trauma scores derived from the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire as predictor variables, only emotional abuse had a statistically significant effect on dissociation scores (F=10.90, df=1, 30, p=0.002).

Discussion

The majority of the patients with conversion disorder (89.5%) still had a psychiatric disorder at follow-up. The most prevalent disorders were anxiety disorders. Somatoform, affective, and dissociative disorders were common as well. These findings suggest that, at least for a subgroup of patients, conversion disorder is part of a chronic and complex psychiatric process that extends transient somatoform symptoms. The subjects in the present study endorsed Dissociation Questionnaire scores (mean=2.6) and Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire scores (mean=58.8) close to that of the DSM-IV dissociative disorder patients in Turkey (3.3 and 52.5, respectively [10, 23]). These scores are markedly above the means for nonclinical populations in Turkey (1.6 and 27.4, respectively). Nevertheless, the structured diagnostic interviews in the present study demonstrated that there is considerable overlap between conversion and dissociative disorders. The comparison between the subjects with and without dissociative disorder, on the other hand, demonstrated that the presence of a comorbid dissociative disorder is a strong indicator for a more chronic and severe psychiatric condition.

The rates of reported childhood physical (44.7%) and sexual abuse (26.3%) in the present study were much higher than the rates obtained in a previous epidemiologic study on a representative female sample derived from the general population in Sivas, Turkey, using the same methodology (28): 8.9% and 2.5%, respectively. Subjects with a dissociative disorder reported childhood sexual and emotional abuse and physical neglect more frequently. A stepwise multiple regression analysis conducted on quantitative scores demonstrated that only emotional abuse had a statistically significant effect on dissociation scores. In accordance with our findings, a recent study on subjects with depersonalization disorder demonstrated that emotional abuse is the most significant predictor of depersonalization but not of general dissociation scores, which were better predicted by combined emotional and sexual abuse (14).

Patients with dissociative disorder reported suicide attempts and self-mutilative behavior more frequently than the remaining subjects. On the other hand, a considerable part (23.7%) of the conversion patients in the present study were diagnosed as having borderline personality disorder, and most of them belonged to the dissociative disorder group. Self-destructive behavior and childhood trauma are known to be common both in borderline personality disorder and in dissociative disorder patients (29–33). Subjects with borderline personality disorder frequently may have dissociative experiences (33), dissociative disorders (34), and somatization disorder (28, 35). This wide overlap between conversion disorder, dissociative disorders, and borderline personality disorder along with dysthymic disorder, major depression, and somatization disorder and the relation of the overall psychopathology to childhood traumata need a comprehensive explanation.

Chu and Dill (6) argued that borderline personality disorder is a type of posttraumatic syndrome involving the mechanism of dissociation. Proposing a new category of “complex” PTSD, van der Kolk and colleagues (36) demonstrated that PTSD, dissociation, somatization, and affect dysregulation represent a spectrum of adaptations to trauma; they often occur together, but traumatized individuals may suffer various combinations of symptoms over time. The low frequency of PTSD in our study group is in accordance with this notion, i.e., response to traumatic life experiences might not be limited to classical PTSD defined in DSM-IV. The ambivalent attitude of the patients without dissociative disorder (high scores for minimization of childhood trauma, i.e., denial) toward their childhood traumata reflects the complexity of response to trauma.

Half of the subjects in the present study had generalized anxiety disorder at the follow-up evaluation. The presence of dissociative disorder did not have any significant effect on generalized anxiety disorder comorbidity. In a previous study on conversion disorder conducted at index admission, the prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder was only 9.0% (37). This discrepancy suggests that generalized anxiety disorder may be part of the natural course of conversion disorder. In contrast with findings in Western Europe (4, 13) and North America (11), none of our patients had substance abuse, eating disorder, somatoform pain disorder, or hypochondriasis. The prevalences of substance abuse and eating disorders are already low in the general population in Turkey compared with Western Europe and North America. The absence of somatoform pain disorder and hypochondriasis, however, may be due to the gender distribution in the study group, i.e., these disorders are known to be more common among men in Turkey.

This study has some limitations. First, it was possible to recruit only 55.9% of all consecutively admitted conversion disorder patients for the follow-up evaluation. The high comorbidity rate and related help-seeking behavior among the contacted patients make a more favorable outcome for excluded subjects probable. Second, most of the patients in the study group had pseudoseizures, and the gender distribution was overwhelmingly female. Nevertheless, pseudoseizure is the most frequently seen conversion symptom in Turkey (15, 37–39), and female patients are usually overrepresented in studies on conversion disorder from Turkey (37–39), Western Europe (4, 13), and North America (11). In an epidemiological study in Turkey (40), although there was no difference in average dissociation score between genders, two times as many women than men were included among high scorers. Thus, the overrepresentation of female participants in our study does not seem to be a selection bias.

Third, the evaluation of the patients by using standardized measures during the index admission would make our findings more concrete. However, the differential diagnosis of a conversion disorder is usually a clinical one, and a follow-up study has the advantage of providing information about the natural course of the disorder.

We conclude that comorbid dissociative disorder among patients with conversion disorder should alert clinicians for the presence of a chronic and complex psychiatric condition. The predominance of acute conversion symptoms in admission should not lead the clinician to overlook the underlying psychopathological process among these patients.

|

|

|

|

|

Presented in part at the 17th international fall conference of the International Society for the Study of Dissociation, San Antonio, Nov. 12–14, 2000. Received May 8, 2003; revision received Sept. 16, 2003; accepted March 4, 2004. From the Clinical Psychotherapy Unit and Dissociative Disorders Program, Department of Psychiatry, Istanbul Medical Faculty, Istanbul University, Istanbul, and Cumhuriyet University Department of Psychiatry, Sivas, Turkey. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Prof. Dr. Şar, Istanbul Tıp Fakültesi Psikiyatri Kliniği, 34390 Çapa, Istanbul, Turkey; [email protected] (e-mail). This study was supported in part by a grant of the Istanbul University Research Fund.

1. van der Kolk BA, van der Hart O: Pierre Janet and the breakdown of adaptation in psychological trauma. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:1530–1540Link, Google Scholar

2. Freud S: Studien über Hysterie (Studies on Hysteria) (1895). Munich, Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1974Google Scholar

3. Saxe GN, Chinman G, Berkowitz R, Hall KH, Lieberg G, Schwartz J, van der Kolk BA: Somatization in patients with dissociative disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1329–1334Link, Google Scholar

4. Spitzer C, Freyberger HJ, Kessler C, Kömpf D: Psychiatrische Komorbiditaet dissoziativer Störungen in der Neurologie (Psychiatric comorbidity of dissociative disorders in a neurological clinic). Nervenarzt 1994; 65:680–688Medline, Google Scholar

5. Nijenhuis ERS, Spinhoven P, Van Dyck R, Van der Hart O, Vanderlinden J: The development and psychometric characteristics of the Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire (SDQ-20). J Nerv Ment Dis 1996; 184:688–694Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Chu JA, Dill DL: Dissociative symptoms in relation to childhood physical and sexual abuse. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:887–892Link, Google Scholar

7. Nijenhuis ERS, Spinhoven P, Van Dyck R, Van der Hart O, Vanderlinden J: Degree of somatoform and psychological dissociation in dissociative disorder is correlated with reported trauma. J Trauma Stress 1998; 11:711–730Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Waller G, Hamilton K, Elliott P, Lewendon J, Stopa L, Waters A, Kennedy F, Lee G, Pearson D, Kennerley H, Hargreaves I, Bashford V, Chalkley J: Somatoform dissociation, psychological dissociation, and specific forms of trauma. J Trauma & Dissociation 2000; 1:81–98Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Kisiel CL, Lyons JS: Dissociation as a mediator of psychopathology among sexually abused children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1034–1039Link, Google Scholar

10. Şar V, Kundakçı T, Kızıltan E, Bakim B, Bozkurt O: Differentiating dissociative disorders from other diagnostic groups through somatoform dissociation in Turkey. J Trauma & Dissociation 2000; 1:67–80Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Bowman ES, Markand ON: Psychodynamics and psychiatric diagnoses of pseudoseizure subjects. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:57–63Link, Google Scholar

12. Pribor EF, Yutzy SH, Dean JT, Wetzel RD: Briquet’s syndrome, dissociation, and abuse. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:1507–1511Link, Google Scholar

13. Spitzer C, Spelsberg B, Grabe HJ, Mundt B, Freyberger HJ: Dissociative experiences and psychopathology in conversion disorders. J Psychosom Res 1999; 46:291–294Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Simeon D, Guralnik O, Schmeidler J, Sirof B, Knutelska M: The role of childhood interpersonal trauma in depersonalization disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1027–1033Link, Google Scholar

15. Sagduyu A, Rezaki M, Kaplan I, Ozgen G, Gursoy-Rezaki B: Saglik ocağgina basvuran hastalarda dissosiyatif (konversion) belirtiler (Prevalence of conversion symptoms in a primary health care center). Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi 1997; 8:161–169Google Scholar

16. Steinberg M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders (SCID-D), Revised. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

17. Kundakçı T, Şar V, Kızıltan E, Yargic LI, Tutkun H: The reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the SCID-D, in Abstracts of the 15th Fall Meeting of the International Society for the Study of Dissociation. Northbrook, Ill, ISSD, 1998Google Scholar

18. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1987Google Scholar

19. Saigh PA, Yasik AE, Oberfield RA, Rubenstein H, Halamandaris P, Nester J, Resko J, Koplewicz H, Inamdar S, McHugh M: The reliability and validity of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Module, in Abstracts of the 14th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. Northbrook, Ill, ISTSS, 1998Google Scholar

20. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (SCID-II). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1987Google Scholar

21. Coskunol H, Bagdiken I, Sorias S, Saygili R: SCID-II Türkce versiyonunun gecerlik ve güvenilirligi (The reliability and validity of the SCID-II Turkish Version). Türk Psikoloji Dergisi 1994; 9:26–29Google Scholar

22. Vanderlinden J, Van Dyck R, Vandereycken W, Vertommen H, Verkes RJ: The Dissociation Questionnaire: development and characteristics of a new self-reporting questionnaire. Clin Psychol Psychother 1993; 1:21–27Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Şar V, Kızıltan E, Kundakçı T, Bakim B, Yargic LI, Bozkurt O: The reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the Dissociation Questionnaire (DIS-Q), in Abstracts of the 15th Fall Meeting of the International Society for the Study of Dissociation. Northbrook, Ill, ISSD, 1998Google Scholar

24. Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Sapareto E, Ruggiero J: Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1132–1136Link, Google Scholar

25. Yargic LI, Şar V, Tutkun H, Alyanak B: Comparison of dissociative identity disorder with other diagnostic groups using a structured interview in Turkey. Compr Psychiatry 1998; 39:345–351Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Walker CE, Bonner BL, Kaufmann K: The Physically and Sexually Abused Child: Evaluation and Treatment. New York, Pergamon Press, 1988Google Scholar

27. Brown GR, Anderson B: Psychiatric morbidity in adult inpatients with childhood histories of sexual and physical abuse. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:55–61Link, Google Scholar

28. Şar V, Akyüz G, Kundakçı T, Doğan O: Prevalence of trauma-related disorders in Turkey: an epidemiological study, in Abstracts of the 14th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. Northbrook, Ill, ISTSS, 1998Google Scholar

29. Şar V, Tutkun H, Alyanak B, Bakim B, Baral I: Frequency of dissociative disorders among psychiatric outpatients in Turkey. Compr Psychiatry 2000; 41:216–222Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. van der Kolk BA, Perry JC, Herman JL.: Childhood origins of self-destructive behavior. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1665–1671Link, Google Scholar

31. Herman JL, Perry JC, Van der Kolk BA: Childhood trauma in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:490–495Link, Google Scholar

32. Ogata SN, Silk KR, Goodrich S, Lohr NE, Westen D, Hill EM: Childhood sexual and physical abuse in adult patients with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:1008–1013Link, Google Scholar

33. Zanarini MC, Ruser T, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J: The dissociative experiences of borderline patients. Compr Psychiatry 2000; 41:223–227Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Şar V, Kundakçı T, Kızıltan E, Yargic LI, Tutkun H, Bakim B, Aydiner O, Ozpulat T, Keser V, Ozdemir O: Axis I dissociative disorder comorbidity in borderline personality disorder among psychiatric outpatients. J Trauma & Dissociation 2003; 4:119–136Crossref, Google Scholar

35. Hudziak JJ, Boffeli TJ, Kriesman JJ, Battaglia MM, Stanger C, Guze SB: Clinical study of the relation of borderline personality disorder to Briquet’s syndrome (hysteria), somatization disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and substance abuse disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:1598–1606Link, Google Scholar

36. van der Kolk BA, Pelcovitz D, Roth S, Mandel FS, McFarlane A, Herman JL: Dissociation, somatization, and affect dysregulation: the complexity of adaptation to trauma. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153(July festschrift suppl):83–93Google Scholar

37. Kaygisiz A, Alkin T: Konversiyon bozukluğunda I, ve II, eksen ruhsal bozukluk estanilari (Axis I and II comorbidity of conversion disorder). Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi 1999; 10:33–39Google Scholar

38. Şar I:1970–1980 yillari arasinda Hacettepe Universitesi Psikiyatri Klinigine yatarak tedavi gören hastalardan “histeri” tanisi alanlarin degerlendirilmesi (A Retrospective Evaluation of Inpatients Diagnosed as “Hysteria” in Hacettepe University Psychiatric Clinic Between 1970 and 1980) (doctoral dissertation). Ankara, Turkey, Hacettepe University, 1983Google Scholar

39. Şar I, Şar V: Konversiyon bozuklugunda belirti dagilimi (Symptom frequencies in conversion disorder). Uludag Üniversitesi Tıp Fakultesi Dergisi 1990; 17:67–74Google Scholar

40. Akyüz G, Doğan O, Şar V, Yargic LI, Tutkun H: Frequency of dissociative identity disorder in the general population in Turkey. Compr Psychiatry 1999; 40:151–159Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar