Dalí (1904–1989): Psychoanalysis and Pictorial Surrealism

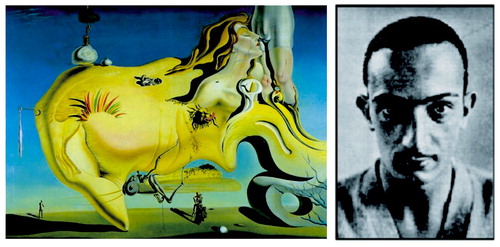

The dream…a huge, heavy head on a threadlike body supported by the prongs of reality…falling into space just as the dream is about to begin.

S. Dalí (1945)

Dalí’s childhood was marked by events that affected his character and work in a psychoanalytical way. He was named after his brother, who had died before Dalí was born. Thus, he was obsessed by the existence of his alter ego and struggled to prove that he himself existed (i.e., that he was not his dead brother, whom he would visit in the cemetery, placing flowers at the gravestone that bore his own name). Sex was another of his main worries. His father, a rich notary and a regular client of prostitutes, believed that his elder son had died of some kind of venereal disease transmitted by him. Therefore, in order to warn the adolescent Salvador of the dangers involved, he gave him books containing pictures of the lesions caused by syphilis. Dalí remembered these illustrations as being frightening and repulsive and came to associate them with sexuality as a whole. This led him to avoid any form of carnal contact and to rely on onanism as his source of pleasure.

Dalí went to Madrid in 1921 to study at the San Fernando Academy of Fine Arts. There he came in contact with the young, surrealist, Spanish avant-garde and formed a very close friendship with the poet Federico García Lorca and the filmmaker Luis Buñuel. It was in Madrid that Dalí discovered psychoanalysis when he read Freud’s Die Traumdeutung, which made a great impression on him: “It was one of the greatest discoveries of my life. I was obsessed by the vice of self-interpretation—not just of my dreams but of everything that happened to me, however accidental it might at first seem” (1).

He met the French surrealists in 1926 during his first visit to Paris. It was there that in 1929 he fell in love with Gala Eluard and made his first contributions to surrealism with works such as Le Grand Masturbateur, in which he displays all his instincts and makes use of Freud’s ideas to reflect his personality, fears, and sexual obsessions. There is an ambiguity in the painting that goes unnoticed at first because of the forcefulness of the drawing and clarity of the images. The main figure in the painting is a stylized self-portrait of the artist himself. His mouth is replaced by a grasshopper whose stomach is covered in ants—synonymous with a praying mantis (from childhood Dalí had had an irrational fear of locusts). This insect is enveloped by the tingling desire of the ants and symbolizes Dalí’s sexual fears. There are symbolic elements attached to his self-portrait: a lion’s head, a hook, the figure of a woman whose face is held close to a man’s genitals, and shells and pebbles. The lion heads that repeatedly appear in Dalí’s paintings represent the repressive, threatening figure of his father. The abundance of soft structures expresses his singular anguish regarding time and space. The 1932 painting Espectro del Sex-Appeal is probably the most impactful representation of Dalí’s fear of sex.

In 1929, Dalí met Lacan. Lacan’s treatise, De la psychose paranoïaque dans ses rapports avec la personnalité, suggested to Dalí the paranoiac-critical method, by means of which the passivity of the automatism of symbols is replaced by the dynamism of the delusion of interpretation. In Dalí’s own words:

“My whole ambition in the pictorial domain is to materialize the images of my concrete irrationality with the most imperialist fury of precision.…Paranoiac-critical activity organizes and objectifies in an exclusivist manner the limitless and unknown possibilities of the systematic association of subjective and objective ‘significance’ in the irrational.” (2)

The concealed relationships between things were revealed to the light of the subconscious’s gaze, resulting in exceptionally rich interpretations, capable of constantly spreading. Dalí’s continuous obsession with the double reading of things can be seen in the anamorphoses. The double images thus produced proliferated in many of Dalí’s paintings, such as the 1938 works El Gran Paranoico and El Enigma Sin Fin.

Along with Buñuel, Dalí made in Paris the first surrealist films—Un Chien Andalou (1929) and L’Age d’Or (1930). Dalí later worked with Hitchcock in the staging of a dream for the 1946 film Spellbound.

In 1938, Dalí met Freud in London where he showed him his 1937 work Metamorfosis de Narciso. Freud, in a letter to S. Zweig, praised the artist’s authenticity and made an exception of Dalí concerning the contempt he felt for surrealists in general:

“Up to now I have been inclined to consider surrealists, who seem to have chosen me as their patron saint, as incurable nutcases. The young Spaniard, however, with his candid, fanatical eyes and unquestionable technical skill has made me reconsider my opinion. In fact, it would be very interesting to investigate the way in which such a painting has been composed.” (3)

Versatile artist, provocative genius, eccentric, and fickle, Dalí was immersed in the conquest of the irrational and never ending search for the unconscious. He made a revolutionary contribution to surrealism, within the framework of Freudian psychoanalysis, using his own disquieting pictorial symbolism and language.

Address reprint requests to Dr. Martínez-Herrera, Medico Interino Residente de Psiquiatria, Hospital General Universitario de Murcia, C/Doctor Gregorio Maranon, 27-4A, 03202 Elche (Alicante), Spain. Photographs courtesy of Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid.

Le Grand Masturbateur (1929), by Salvador Dalí (1928 photograph)

1. Dalí S: The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (1942). Mineola, NY, Dover Publications, 1993Google Scholar

2. Dalí S: La conquète de l’irrationnel. Paris, Éditions Surréalistes, 1935Google Scholar

3. Caparrós N: Correspondencia de Sigmund Freud. Madrid, Tomo V Imago, 2002Google Scholar