Mental Disorders and Quality of Diabetes Care in the Veterans Health Administration

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The population of persons with mental disorders is potentially vulnerable to poor quality of medical care. This study examined the relationship between mental disorders and quality of diabetes care in a national sample of veterans. METHOD: Chart-abstracted quality data were merged with outpatient and inpatient administrative database records for a sample of veterans with diabetes who had at least three outpatient visits in the previous year (N=38,020). Mental health diagnoses were identified by use of the administrative data. Quality of diabetes care was assessed with five indicators by chart documentation: annual foot inspection, pedal pulses examination, foot sensory examination, retina examination, and glycated hemoglobin determination. RESULTS: Approximately a quarter of the sample had a diagnosed mental disorder (23.7% with psychiatric disorder only, 1.3% with substance use disorder only, and 2.6% with a dual diagnosis). Overall rates of receipt for the indicators were higher than national benchmarks for all patient subgroups, ranging from 70.8% for retina examination to 95.0% for foot inspection. Rates for both retina examination and foot sensory examination differed significantly by mental health status, mainly because of lower rates among those with a substance use disorder. The associations remained significant in multivariate generalized estimating equation analyses that controlled for demographic characteristics, health status, use of medical services, and hospital-level characteristics. CONCLUSIONS: Rates for secondary prevention of diabetes were remarkably high at Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers, although patients with mental disorders (particularly substance use disorders) were somewhat less likely to receive some of the recommended interventions.

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common and costly chronic medical conditions in the United States. Diabetes affects approximately 16 million persons and is a leading cause of death (1). It is estimated that diabetes and its complications account for nearly $100 billion in expenditures annually (2).

Studies have shown that there is substantial comorbidity between mental illness and diabetes (3, 4), and a growing body of literature is focused on the link between the two. The use of antipsychotics (5, 6) and antidepressants (7) as well as higher rates of obesity, poor diet, physical inactivity, and smoking (8, 9) all serve to increase the risk of diabetes among the mentally ill. In addition, higher mortality due to diabetes has been observed among mentally ill individuals than in the general population (10, 11).

Among patients with diagnosed diabetes, depression has been associated with adverse outcomes, including poor glycemic control (12) and diabetic complications (13). Evidence from controlled trials, however, suggests that pharmacologic (14, 15) and nonpharmacologic (16) treatments of depression may improve glycemic control.

Many of the complications of diabetes—such as foot ulcers, amputations, neuropathy, and blindness—are largely preventable, and groups such as the American Diabetes Association have issued clinical guidelines and standards for the management of patients with diabetes (17). Given that persons with mental disorders are at a greater risk for diabetes-related morbidity and mortality and that they represent a population that is potentially vulnerable to poorer quality of medical care (18–21), it is important to focus attention on the quality of diabetes care received by such patients.

To date, we are aware of no empirical studies that have examined the association between mental illness and quality of diabetes care. In the present study, we examined this relationship in a national sample of veterans with diabetes. We hypothesized that patients with mental disorders receive poorer quality of care than do those with no mental disorder, as determined by five chart-based quality indicators (chart documentation of foot inspection, pedal pulses examination, foot sensory examination, retina examination, and glycated hemoglobin determination in the past year), with control for demographic characteristics, health status, use of medical services, and hospital-level characteristics.

Method

Data Sources and Study Sample

The Veterans Health Administration is the largest fully integrated health care system in the United States, providing care to nearly 3.5 million persons annually (22). As part of the Veterans Health Administration’s External Peer Review Program, medical records are sampled and reviewed on an ongoing basis to monitor the quality and appropriateness of care delivered at Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (23). Data for the present study were collected between January 1998 and December 1999. A total of 600 medical charts were randomly selected at each VA facility by using computerized administrative records. The External Peer Review Program sampling frame included veterans with selected high-volume medical diagnoses—including diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and obesity—who had at least three medical outpatient visits in the past year. For this study, we focused on 38,020 patients with chart-documented diabetes. Trained reviewers, blind to the study hypothesis, abstracted paper and/or electronic records looking for evidence of receipt of the quality indicators in the past year. Quarterly assessments of interrater reliability yielded kappa values greater than 0.95.

With the use of social security numbers, the External Peer Review Program chart-review data were merged with three national VA administrative databases (Patient Encounter File, Outpatient File, and Patient Treatment File). Taken together, these three files detail all outpatient and inpatient care received at VA facilities. The administrative data were used to identify patients with mental health diagnoses who were treated at VA facilities as well as to ascertain patients’ demographic characteristics and history of health services use.

Measures

We used Veterans Health Administration outpatient and inpatient administrative database records for the year prior to the External Peer Review Program selection date to identify persons with a diagnosed mental disorder (ICD-9 codes 290–319). We categorized patients into one of four mutually exclusive diagnostic groups: no mental disorder, psychiatric disorder only (ICD-9 codes 290–302 and 306–319), substance (alcohol or drug) use disorder only (ICD-9 codes 303–305), or dual diagnosis (comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders). In addition, we examined the relationship between quality of care and specific serious psychiatric illnesses, including major affective disorder (ICD-9 code 296), schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder (ICD-9 codes 295, 297, 298), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (ICD-9 code 308). Finally, using mental health inpatient stay as a proxy for severity of mental illness, we determined whether patients who had had an inpatient stay in the previous year were at an even greater risk for poorer quality of diabetes care.

The outcome of interest was quality of diabetes care. Quality of care was assessed by use of five indicators abstracted from the medical record: chart documentation in the past year of 1) foot inspection, 2) pedal pulses examination, 3) foot sensory examination, 4) examination of the retina, and 5) determination of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) (22). These indicators of quality reflect nationally recognized guidelines for appropriate care of patients with diabetes. In addition to examining each of the five indicators individually, we created a summary index with a possible range of 0 to 5 to reflect the total number of interventions received in the past year.

In multivariate analyses, we controlled for a variety of potential confounders, including demographic characteristics, health status, use of medical services, and facility characteristics. The following demographic characteristics were obtained from administrative data: age, sex, race (white, black, Hispanic, or other), level of VA service connectedness (i.e., degree to which veteran has priority access to Veterans Health Administration care) (24), and distance from veteran’s home to nearest VA medical center (25). Because information on race was missing for a substantial proportion (20%) of patients, a dummy variable for missing race was included in all models. Health status was defined as the total number of comorbid medical conditions included in the External Peer Review Program data (possible range=0 to 4). Additionally, three variables were used to quantify use of medical services in the previous year: number of primary care visits (defined as visits to the primary care, general internal medicine, or women’s clinic), number of specialty medical visits, and number of medical inpatient days. These variables likely reflect both greater medical morbidity as well as more opportunities for receiving diabetes-related interventions for those who had not received them at previous visits. Finally, we examined three VA facility-level variables: academic emphasis (the proportion of funds spent on teaching and research), hospital size (the total number of patients treated per year), and mental health emphasis (the proportion of funds spent on mental health versus general health care) (26, 27).

Statistical Analysis

Sample characteristics of patients in the four dual-diagnosis categories were compared by using chi-square tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance with F tests for continuous variables. Next, for each indicator, we calculated the percentage of patients with chart-documented receipt of the intervention in the past year. In addition, we calculated a summary index and presented both the percentage of patients who received all five interventions and the mean number of interventions received. Both overall results and results stratified by mental health diagnostic category are presented. Bivariate associations between mental health status and the quality indicators were assessed with chi-square tests and F tests, as appropriate.

Finally, multivariate methods were used to examine the relationship between mental disorders and quality of diabetes care, with control for demographic characteristics, health status, use of medical services, and facility characteristics. Generalized estimating equation modeling was used to incorporate both individual-level and facility-level covariates and to account for the clustering of patients within facilities (28). For dichotomous outcomes, we specified the logit link function and binary distribution. We specified the identity link function and normal distribution when the outcome was the continuous summary index score (i.e., total number of interventions received). Since the quality of diabetes care has been improving over time in the VA system (22), all of the models also included a variable indicating the quarter in which the data were collected to help account for secular trends in quality improvement. To determine whether any observed differences in quality between patients with and without mental disorders have narrowed as a result of overall trends in quality improvement, we also tested mental health-by-quarter interaction terms. All analyses were performed with SAS version 6.12 (29).

Results

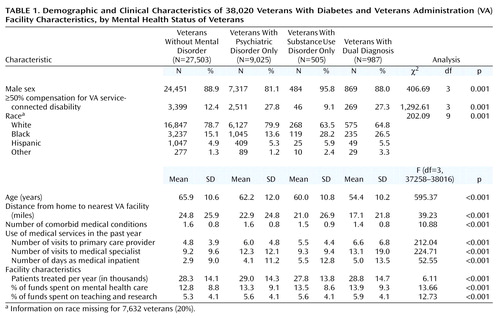

The study sample included 38,020 patients with diabetes from 146 VA medical centers. Overall, more than a quarter of the sample had a diagnosed mental disorder (23.7% [N=9,025] with psychiatric disorder only, 1.3% [N=505] with substance use disorder only, and 2.6% [N=987] with a dual diagnosis). The prevalence of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder was 4.3% (N=1,616); major affective disorder, 7.7% (N=2,931); and PTSD, 5.3% (N=2,023). Table 1 presents a description of the sample. In general, compared with patients without mental disorders, mentally ill patients were more likely to be younger, female (except those with a substance use disorder only), and nonwhite. Persons with a psychiatric disorder or dual diagnosis were more than twice as likely as those without mental disorders to receive VA compensation for a ≥50% service-connected disability; patients with a substance use disorder only were the least likely to have a service-connected disability. On average, patients with a mental disorder lived closer to a VA medical center, had fewer comorbid medical conditions, and used more outpatient and inpatient medical services in the previous year than patients without a mental disorder. In addition, those with a mental disorder were more likely to be treated at VA facilities that spend a greater proportion of funds on teaching and research, are larger in terms of annual patient volume, and spend a greater proportion on mental health versus general health care.

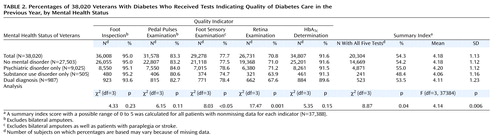

Table 2 presents the percentage of patients with chart-documented receipt of the diabetes quality indicators. Overall rates for the individual indicators were high, ranging from 70.8% for retina examination to 95.0% for foot inspection; however, only 54.3% of the sample received all five medical interventions in the past year. On average, patients received 4.18 interventions.

In unadjusted analyses, rates for two of the five quality indicators—retina examination and foot sensory examination—differed significantly by mental health status, primarily because of lower rates among those with a substance use disorder only (Table 2). In these data, we did not find consistent evidence that patients with a serious psychiatric illness (namely, major affective disorder, psychotic disorders, or PTSD) or patients who had had a mental health inpatient stay were at any greater risk for poorer quality of diabetes care (data not shown). The observed associations between substance use disorder and quality of care remained significant after control for potential confounders and did not significantly change over the study period as overall quality improved (data not shown).

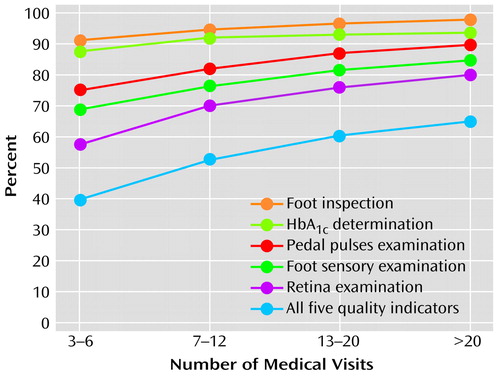

Overall, contrary to our hypothesis, persons with psychiatric disorders did not receive poorer quality of care than those without such disorders (Table 2). The fact that patients with psychiatric disorders had significantly more medical outpatient visits in the previous year than other patients (Table 1) and that the number of visits was positively associated with the likelihood of receiving the quality indicators (Figure 1) suggests that the high quality of care received by persons with a psychiatric disorder might have been, at least in part, attributed to their greater use of medical services and, therefore, more opportunities for receiving the interventions. Indeed, whereas rates for retina examination, for example, were nearly identical among patients with a psychiatric disorder only (71.2%) compared with those without a mental disorder (71.0%) in unadjusted analyses (Table 2), a significant negative association was found in multivariate analyses with control for medical visits (odds ratio=0.86, p<0.001). A similar relationship was found with respect to HbA1c determination but not the other quality indicators (data not shown).

In addition to mental health status and the number of medical visits, several other study variables were significantly associated with receipt of the quality indicators (data not shown). Higher quality index scores were found among male, black, and Hispanic patients as well as patients who were at least 50% VA service connected and who had fewer comorbid medical conditions. The number of medical inpatient days was positively associated with foot inspection and pedal pulses examination but negatively associated with retina examination and HbA1c determination. Quality of diabetes care differed little by facility-level characteristics, with the following exceptions: patients who sought care either at larger hospitals or at hospitals that spend a greater proportion of funds on mental health were less likely to have their feet inspected, while patients treated at VA medical centers with a greater academic emphasis were more likely to have their glycated hemoglobin levels checked.

Discussion

In this large national sample of veterans with diabetes, we found remarkably high rates of receipt for five quality-of-care indicators, ranging from 70.8% for retina examination to 95.0% for foot inspection; on average, patients received 4.18 interventions in the previous year. These observed rates for diabetes-related secondary prevention measures exceed national performance standards for managed-care organizations (30) as well as rates reported in population-based samples (31–34). For example, according to data from the 2000 Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (30), mean rates for HbA1c testing and eye examinations were 75.1% and 45.3%, respectively, across health plans. Of note, even the rates we observed among patients with mental disorders exceed these national benchmarks. Caution is warranted, however, when making comparisons across health care systems because of differences in the methods for obtaining these measures (35). The high rates of compliance with the quality indicators and the modest differences by mental health status may, in part, be attributed to the regular feedback provided by the External Peer Review Program to VA medical center clinical leaders and administrators. In addition, the VA’s use of electronic medical records is likely to promote greater coordination of patient care.

Contrary to our hypothesis, we found little difference in quality of diabetes care between patients with and without mental disorders. Rates for two of the five indicators—retina examination and foot sensory examination—differed significantly by mental health status in unadjusted analyses, primarily because of lower rates among the relatively small group of patients with substance use disorders. The associations remained significant even after control for a variety of demographic characteristics, health status, use of medical services, and facility characteristics.

Both patient and provider factors may have contributed to the observed differences in quality of care. With respect to receiving an annual retina examination, for example, patients with substance use disorders may have been less likely, for a variety of reasons, to receive and/or follow-up on ophthalmological referrals. Studies have found that generalists often have difficulty serving the medical needs of patients with substance use disorders (36). In addition, such patients are often stigmatized by health care providers (37), which may further serve to interfere with the delivery of appropriate care. Moreover, the cognitive, affective, and behavioral symptoms associated with mental disorders may hinder effective, collaborative patient-physician communication, which has been shown to be important in improving adherence and outcomes for chronic medical conditions (38–40).

It is not clear why a more consistent pattern of associations was not found across all of the quality indicators. Although we cannot exclude the role of chance or potential errors in abstracting or coding the data, it is interesting to note that interventions such as the foot inspection and pedal pulses examination, for which no significant difference in quality was observed, are simple procedures performed by a single provider. In contrast, receipt of a retina examination—the intervention for which the greatest disparity was observed—requires a coordinated effort from referral to scheduling an appointment to follow through by the patient. Although it was based on a relatively small number of patients, the finding that persons with substance use disorders were less likely to have had a retina examination in the previous year is important given that diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness among adults in the United States (41) and can be prevented if detected early.

The findings of this study may not apply to non-VA settings. Indeed, unique aspects of the study population and the Veterans Health Administration system suggest that these findings likely underestimate the difference in diabetes care received by persons with and without mental disorders in other health care settings. First, this was a select sample in that all of the patients had at least three outpatient visits in the past year, suggesting that they were well engaged with the medical system. Second, the Veterans Health Administration is a fully integrated health care system geared toward caring for the mentally ill, with approximately 20% of the general patient population having a mental disorder (26). Third, unlike those in other settings, patients in the Veterans Health Administration system do not face constraints on health care services use. In other settings, which are more fragmented or which attempt to contain costs by limiting outpatient services, mentally ill patients may be at greater risk for poorer quality of care.

This is underscored by our finding that number of medical visits appeared to be a mediator in this study, such that patients with a psychiatric disorder seemed to receive similar quality of care as those without a mental disorder, in part, as a result of more visits. In other words, we found that vulnerability conferred by mental illness was, to some extent, compensated for by more use of medical services. In national surveys, mentally ill persons have reported worse health insurance coverage (42) and poorer access to care (42, 43) than those without a mental disorder; therefore, this compensatory effect of greater use may not operate in other health care settings. Future studies should examine the relationship between mental illness and quality of diabetes care in other patient populations and settings.

Although not a primary focus of this study, several other variables were significantly associated with quality of diabetes care and deserve brief comment. It is not clear why men received better diabetes care than women. While it has been observed that the Veterans Health Administration is a male-dominated system geared to treat a mostly male population and that female veterans underuse VA health services (44, 45), the association persisted even after control for use of medical services. Moreover, this finding is consistent with a population-based study of persons with diabetes (31), suggesting that the gender difference in quality is not unique to the VA setting.

It is also not clear why black and Hispanic patients tended to receive better care than others. It may be that they had more severe diabetes or had been living with their disease longer, resulting in greater awareness and recognition of the need for preventive care. Unfortunately, data were not available on factors such as specific disease severity or age at diagnosis. We found that the number of comorbid medical conditions was inversely associated with two of the indicators as well as the summary index. The presence of comorbidities may decrease the time and attention that can be devoted to any given condition (20).

This study had the following limitations. First, our ability to control for potential confounders, such as race and medical comorbidity, was limited by the quality of the available administrative and chart-review data. Second, we did not have data on health care received outside of the VA system. Given that some veterans likely received additional medical services in non-VA settings, we may have underestimated the percentage of patients who received diabetes care in the past year. This underestimation, however, likely resulted in a bias toward the null, since patients without mental disorders may have been more likely to receive non-VA care, given, in part, their older age and greater Medicare eligibility.

In conclusion, rates for secondary prevention of diabetes were higher at VA medical centers than on national benchmarks; however, patients with substance use disorders were less likely than other patients to receive some of the recommended interventions, placing them at some greater risk for diabetes-related complications and disability as well as high health care costs. Strategies such as case management, extra time for office visits, and other interventions developed for the management of chronic illnesses (46) may need to be adapted for use in patients with mental disorders. More work is needed to develop and test models for improving care in this vulnerable population.

|

|

Received June 22, 2001; revision received Oct. 2, 2001; accepted April 1, 2002. From the Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT; the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, West Haven; and the Office of Quality and Performance, Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC. Address reprint requests to Dr. Desai, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, NEPEC (182), 950 Campbell Ave., West Haven, CT 06516; [email protected] (e-mail). The authors thank Thomas Craig, M.D., and Steven Wright, Ph.D., for their comments on a previous version and Dean Bross, Ph.D., for his help with data from the External Peer Review Program.

Figure 1. Percentages of 38,020 Veterans With Diabetes Who Received Tests Indicating Quality of Diabetes Care in the Previous Year, by Number of Medical Visitsa

aChi-square for linear trend was significant (p<0.001) for each of the five indicators as well as for the summary index.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Diabetes Surveillance, 1997. Atlanta, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1997Google Scholar

2. American Diabetes Association: Economic consequences of diabetes mellitus in the US in 1997. Diabetes Care 1998; 21:296-309Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ: The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2001; 24:1069-1078Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Lustman PJ: Anxiety disorders in adults with diabetes mellitus. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1988; 11:419-432Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Henderson DC, Cagliero E, Gray C, Nasrallah RS, Hayden DL, Schoenfeld DA, Goff DC: Clozapine, diabetes mellitus, weight gain, and lipid abnormalities: a five-year naturalistic study. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:975-981Link, Google Scholar

6. Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, Chandler LP, Cappelleri JC, Infante MC, Weiden PJ: Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:1686-1696Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Fava M: Weight gain and antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61(suppl 11):37-41Google Scholar

8. Brown S, Birtwistle J, Roe L, Thompson C: The unhealthy lifestyle of people with schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1999; 29:697-701Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH: Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA 2000; 284:2606-2610Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B: Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 177:212-217Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Ösby U, Correia N, Brandt L, Ekbom A, Sparén P: Mortality and causes of death in schizophrenia in Stockholm County, Sweden. Schizophr Res 2000; 45:21-28Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, de Groot M, Carney RM, Clouse RE: Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care 2000; 23:934-942Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ: Association of depression and diabetic complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2001; 63:619-630Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Clouse RE, Freedland KE, Eisen SA, Rubin EH, Carney RM, McGill JB: Effects of nortriptyline on depression and glycemic control in diabetes: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Psychosom Med 1997; 59:241-250Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Lustman PJ, Freedland KE, Griffith LS, Clouse RE: Fluoxetine for depression in diabetes: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2000; 23:618-623Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Freedland KE, Kissel SS, Clouse RE: Cognitive behavior therapy for depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1998; 129:613-621Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2000; 23(1 suppl):S32-S42Google Scholar

18. Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM: Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA 2000; 283:506-511Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Desai MM, Bruce ML, Kasl SV: The effects of major depression and phobia on stage at diagnosis of breast cancer. Int J Psychiatry Med 1999; 29:29-45Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Redelmeier DA, Tan SH, Booth GL: The treatment of unrelated disorders in patients with chronic medical diseases. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:1516-1520Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, Perlin JB: Mental disorders and quality of care among postacute myocardial infarction outpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002; 190:51-53Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Kizer KW: The “new VA”: a national laboratory for health care quality management. Am J Med Qual 1999; 14:3-20Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Halpern J: The measurement of quality of care in the Veterans Health Administration. Med Care 1996; 34(3 suppl):MS55-MS68Google Scholar

24. Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA: Cross-system service use among psychiatric patients: data from the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Behav Health Serv Res 2000; 27:98-106Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Rosenheck R, Stolar M: Access to public mental health services: determinants of population coverage. Med Care 1998; 36:503-512Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Rosenheck R, DiLella D: Department of Veterans Affairs National Mental Health Program Performance Monitoring System: Fiscal Year 1999 Report. West Haven, Conn, Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 2000Google Scholar

27. Leslie DL, Rosenheck R: The effect of institutional fiscal stress on the use of atypical antipsychotic medications in the treatment of schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 2001; 189:377-383Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Liang K-Y, Zeger SL: Regression analysis for correlated data. Annu Rev Public Health 1993; 14:43-68Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. SAS Version 6.12. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1996Google Scholar

30. National Committee for Quality Assurance: The State of Managed Care Quality. Washington, DC, NCQA, 2000Google Scholar

31. Ahluwalia HK, Miller CE, Pickard SP, Mayo MS, Ahluwalia JS, Beckles GLA: Prevalence and correlates of preventive care among adults with diabetes in Kansas. Diabetes Care 2000; 23:484-489Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Brechner RJ, Cowie CC, Howie LJ, Herman WH, Will JC, Harris MI: Ophthalmic examination among adults with diagnosed diabetes mellitus. JAMA 1993; 270:1714-1718Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Weiner JP, Parente ST, Garnick DW, Fowles J, Lawthers AG, Palmer RH: Variation in office-based quality: a claims-based profile of care provided to Medicare patients with diabetes. JAMA 1995; 273:1503-1508Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Chin MH, Auerbach SB, Cook S, Harrison JF, Koppert J, Jin L, Thiel F, Karrison TG, Harrand AG, Schaefer CT, Takashima HT, Egbert N, Chiu S-C, McNabb WL: Quality of diabetes care in community health centers. Am J Public Health 2000; 90:431-434Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Jones D, Hendricks A, Comstock C, Rosen A, Chang BH, Rothendler J, Hankin C, Prashker M: Eye examinations for VA patients with diabetes: standardizing performance measures. Int J Qual Health Care 2000; 12:97-104Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. McGillion J, Wanigaratne S, Feinmann C, Godden T, Byrne A: GPs’ attitudes towards the treatment of drug misusers. Br J Gen Pract 2000; 50:385-386Medline, Google Scholar

37. Ritson EB: Alcohol, drugs and stigma. Int J Clin Pract 1999; 53:549-551Medline, Google Scholar

38. Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE, Walker EA: The patient-provider relationship: attachment theory and adherence to treatment in diabetes. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:29-35Link, Google Scholar

39. Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE: Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care 1989; 27(3 suppl):S110-S127; correction, 27:679Google Scholar

40. Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner EH: Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med 1997; 127:1097-1102Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Aiello LP, Gardner TW, King GL, Blankenship G, Cavallerano JD, Ferris FL, Klein R: Diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 1998; 21:143-156Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Sturm R, Wells K: Health insurance may be improving—but not for individuals with mental illness. Health Serv Res 2000; 35(1, part 2):253-262Google Scholar

43. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA: Mental disorders and access to medical care in the United States. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1775-1777Link, Google Scholar

44. Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA: Utilization of mental health services by women in a male-dominated environment: the VA experience. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48:1408-1414Link, Google Scholar

45. Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA: Female veterans’ use of Department of Veterans Affairs health care services. Med Care 1998; 36:1114-1119Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M: Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q 1996; 74:511-544Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar