Efficacy of St. John’s Wort Extract WS 5570 in Major Depression: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial with 375 patients the authors investigated the antidepressant efficacy and safety of 300 mg t.i.d. of hydroalcoholic Hypericum perforatum extract WS 5570. METHOD: The study participants were male and female adult outpatients with mild to moderate major depression (single or recurrent episode, DSM-IV criteria). After a single-blind placebo run-in phase, the patients were randomly assigned, 186 to WS 5570 and 189 to placebo, after which they received double-blind treatment for 6 weeks. Follow-up visits were held after 1, 2, 4, and 6 weeks. The primary outcome measure was the change from baseline in the total score on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. In addition, analyses of responders (patients with at least a 50% reduction in Hamilton total score) and patients with remissions (patients with a total score of 6 or less on the Hamilton scale at treatment end) were carried out, and subscale/subgroup analyses were conducted. The design included an adaptive interim analysis performed after random assignment of 169 patients with options for group size adjustment or early termination. RESULTS: Compared to placebo, WS 5570 produced a significantly greater reduction in total score on the Hamilton depression scale and significantly more patients with treatment response or remission. It was more effective in patients with higher baseline Hamilton scores and led to global reduction of depression-related core symptoms, assessed with the melancholia subscale of the Hamilton scale. The placebo and WS 5570 groups had comparable adverse events. CONCLUSIONS: H. perforatum extract WS 5570 was found to be safe and more effective than placebo for the treatment of mild to moderate depression.

After decades of predominant reliance on synthetic antidepressants, the treatment of mildly and moderately severe forms of major depression with extracts from St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) is becoming increasingly popular, with sales of $86 million in the U.S. market during 2000. Today, preparations based on H. perforatum extract are among the most widely prescribed drugs for depression in many European countries.

The efficacy of drugs based on H. perforatum in alleviating mild to moderate depressive states was confirmed in comparisons with placebo and with effective synthetic standard antidepressants (e.g., imipramine, fluoxetine); reviews and meta-analyses have been conducted by Kim et al. (1), Linde et al. (2), and Volz (3). It has been claimed that H. perforatum is associated with fewer and less severe side effects than its active comparators (see references 1, 4–6). Despite the large body of published evidence supporting the efficacy of H. perforatum extract as an antidepressant, reviewers (1, 7) have identified serious design problems in existing studies and have criticized the meagerness of the database. Even in cases of a positive response with a classical scale such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (8, 9), one may question whether the observed score changes reflect a true antidepressant effect. Therefore, quantitative and qualitative data for assessing the antidepressant efficacy of H. perforatum extract in relation to placebo are welcome.

An aspect with potentially important clinical implications is the initial severity of the patient’s depression and its relationship to treatment efficacy. Laakmann and colleagues (10) investigated mildly to moderately depressed patients with a pretreatment total score on the Hamilton depression scale (17-item version) of 17 or higher, and they suggested that antidepressant treatment with H. perforatum extract was more efficacious for the more severely depressed subgroup (those with an initial total score on the Hamilton scale of 22 or higher).

The aim of the present study was to compare the efficacy of H. perforatum extract WS 5570 to that of placebo in a large group of patients suffering from a mild to moderate major depressive episode according to DSM-IV. In addition, particular attention was paid to the efficacy observed for the core symptoms of depression, as measured by the Bech melancholia scale (11), and to the relationship between the initial severity of depression and response to treatment.

Method

This was a 6-week double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase III trial comparing the efficacy of WS 5570, 300 mg t.i.d., and placebo. The investigation was conducted by the Hypericum Study Group between July 1997 and June 2000 in 26 clinical centers in France. The European Union’s Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki, and national regulatory and legal requirements (French Code of Public Health), including approval of the trial protocol by an independent ethics committee, were observed. After complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Centers and Subjects

The study participants were recruited from the pool of patients who sought treatment for depression in any of the clinical centers and who met the trial’s entry criteria. Most centers were outpatient departments associated with psychiatric inpatient departments, while other centers were situated in private practices. Patient inclusion and all evaluations of ratings were conducted by psychiatrists. All investigators participated in specific training to identify and include patients with the appropriate diagnosis. They were trained to use a structured interview, the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (12, 13). Standardization of ratings was ensured by the rating of videotaped patient interviews by all investigators and subsequent discussion of appropriate ratings. One videotaped patient was at the upper range of severity (mean total score on Hamilton depression scale=26.3, SD=2.0); a second patient was at the lower end of the range (mean score=20.8, SD=1.5). None of the selected investigators showed a rating deviating by more than two standard deviations from the mean rating.

A patient was eligible for the study if he or she 1) was an outpatient aged 18 to 65 years at the time of screening, 2) provided written informed consent, 3) had a current major depressive episode of at least 2 weeks’ duration that met the criteria of DSM-IV code 296.21, 296.22, 296.31, or 296.32 (mild or moderate depression, single or recurrent episode), and 4) had a total score on the Hamilton depression scale between 18 and 25 and a score on item 1 (“depressed mood”) of 2 or higher at screening and baseline. The reasons for exclusion were depression of any type other than those specified, any serious psychiatric disease other than depression, serious suicidal risk (score of 3 or higher on item 3 of the Hamilton depression scale), or response to placebo during the run-in phase; response was defined as a 25% or greater reduction of the Hamilton depression scale total score.

Investigational Treatments

WS 5570 is a hydroalcoholic extract from Herba hyperici (drug-to-extract ratio, 4–7:1) with standardized contents of 3%–6% hyperforin and 0.12%–0.28% hypericin according to high-performance liquid chromatography. The drug was presented in film-coated tablets, each of which contained 300 mg of the extract.

The tablets containing placebo were indistinguishable from those containing WS 5570 in all aspects of their outward appearance.

Procedure

After giving written informed consent, the patients underwent a screening examination to determine their eligibility for the trial and entered a single-blind placebo run-in period of 3 days for patients who did not need a wash-out and at least 7 days when medications had to be withdrawn before randomized treatment. During a baseline examination (day 0) with reassessment of the entry criteria, eligible patients were randomly assigned at a ratio of 1:1 to treatment with 300 mg t.i.d. of H. perforatum extract WS 5570 or placebo administered over 6 weeks (14). Efficacy and safety were evaluated after 7, 14, 28, and 42 days of randomized treatment.

Measures of Efficacy and Safety

The primary outcome measure for treatment efficacy was the change in the total score on the Hamilton depression scale (17-item version) in the intention-to-treat data set between baseline (day 0) and subsequent visits during randomized treatment. The reliability and validity of the Hamilton depression scale for this population have been previously demonstrated (15). Secondary measures of efficacy were the total score on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (16), the score on the 58-item version of the Symptom Check List (SCL-58) (17), and the Clinical Global Impression (18).

In addition to the total score on the Hamilton depression scale, the melancholia subscore was analyzed. The melancholia subscale was derived from work by Bech and colleagues (11), who applied three formal psychometric criteria (calibration, ascending monotonicity, dispersion) to each item of the Hamilton depression scale. The additive combination of the six items that fulfilled all three criteria was suggested by the authors as a “valid subscale” of the Hamilton depression scale that primarily includes the items that measure the core symptoms of depression. The secondary analysis of the Hamilton scale also included an assessment of responder rates, which were determined as the percentage of patients in each treatment group whose total score on the Hamilton depression scale at the end of treatment was at least 50% lower than at baseline.

Safety measures comprised physical examinations and laboratory tests before and after double-blind treatment (glucose, sodium, potassium, aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, γ-glutamyltransferase, serum creatinine, thyrotropin, hemoglobin, hematocrit, RBC count, WBC count and differential, platelet count). Vital signs were tested at each of the visits. In addition, the patients were thoroughly questioned for adverse events in a general inquiry during all follow-up visits.

Statistical Analysis

Previous investigations of mild to moderate depression have shown that the extent of the response to placebo treatment is hardly predictable in advance and tends to be very variable; for instance, in the 13 placebo-controlled studies reviewed by Linde et al. (2), the rates of response with placebo treatment ranged from 0% to 54%. In addition, the studies also showed striking differences regarding the magnitude of the within-group variability of the response to treatment. To avoid the ethically questionable exposure of an unnecessarily large number of depressed patients to placebo and to minimize the risk of insufficient statistical power, we planned and conducted our study with an adaptive interim analysis (19). Depending on the results of the interim analysis, the study would stop with early rejection or acceptance of the null hypotheses to be tested or it would continue with a second stage in which the number of subjects would be determined by using the results of the first study part. The overall significance level for confirmatory analysis was α=0.025, one-sided, according to guideline E9 of the International Conference on Harmonization (20) (this corresponds to a two-sided level of α=0.05). The boundaries for early rejection or acceptance of a null hypothesis in the interim analysis were α1=0.0153 or α0=0.20 (both one-sided). If the one-sided p value of the first stage, p1, lay between these boundaries (α1<p1< α0), the study would continue with a second part. The null hypothesis could then be rejected if p1·p2≤0.0038, where p2 is the one-sided p value determined from the second stage of the study. These boundaries were computed from the methodology given by Bauer and Koehne (19). In the confirmatory analysis, comparisons of treatment groups were performed for the differences in Hamilton depression scale total score between baseline and day 42, day 28, day 14, and day 7. A null hypothesis was tested only if the results of the preceding tests were significant so that the experiment-wise type I error rate would be controlled without an adjustment of the significance level (21).

The hypotheses were evaluated by using two-sample t tests. All other analyses were purely descriptive without adjustment for multiplicity. For the assessment of the course of change in Hamilton depression score during treatment, a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied. To investigate the relationship between treatment efficacy and the severity of depression before the start of treatment, an explorative subgroup analysis was conducted for patients with an initial Hamilton depression scale total score of less than 22 and for those with a score of 22 or higher.

The primary analysis of efficacy was based on the intention-to-treat principle and included all randomly assigned patients. An additional per-protocol analysis of the patients without major protocol deviations was conducted for the primary outcome measure. For all efficacy analyses, the last observation was carried forward for patients who terminated the trial prematurely. Safety analyses were based on all patients who took at least one dose of the study medication after random assignment.

Results

Patient Accountability

In the first part of the trial, 169 patients were randomly assigned to double-blind treatment (WS 5570: N=84; placebo: N=85), and 206 patients were randomly assigned in the second part after the interim analysis (WS 5570: N=102; placebo: N=104). Therefore, totals of 186 and 189 patients were randomly assigned to treatment with WS 5570 and placebo, respectively, and were included in the intention-to-treat analysis. After random assignment, 18 patients in the WS 5570 group (9.7%) and 25 in the placebo group (13.2%) terminated treatment prematurely. The primary reasons for early withdrawal were lack of efficacy (WS 5570: N=10, 5.4%; placebo: N=14, 7.4%), revocation of informed consent (WS 5570: N=4, 2.2%; placebo: N=7, 3.7%), and adverse events (WS 5570: N=2, 1.1%; placebo: N=2, 1.1%). The per-protocol analysis of all patients without major protocol violations included 164 patients in the WS 5570 group and 157 patients in the placebo group. The decisions with respect to the relevance of the protocol deviations were made before the code was broken.

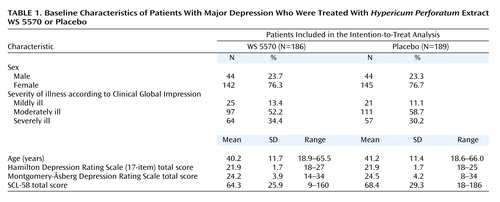

Baseline Characteristics

Basic demographic characteristics and ratings of pretreatment severity of illness for the patients included in the intention-to-treat analysis are presented in Table 1. The data show that the two treatment groups were essentially comparable at baseline. In particular, there were no relevant differences regarding the patients’ severity of depression according to the total scores on the Hamilton depression scale and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.

Efficacy

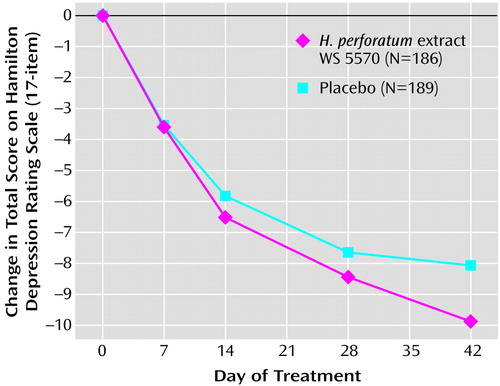

Between the start of randomized treatment and day 42, both groups’ average total scores on the Hamilton depression scale decreased monotonically (Figure 1). Starting from baseline mean values of 21.9 points (SD=1.7) in both treatment groups, the Hamilton depression total score decreased during the treatment phase by a mean of 9.9 points (SD=6.8) in the WS 5570 group and by 8.1 points (SD=7.1) in the placebo group (pooled data from both study stages; last observation carried forward).

In the confirmatory hypothesis testing for the primary outcome measure for the first study stage, i.e., the interim analysis for the intention-to-treat data set, the null hypothesis relating to the difference between treatment groups in the decrease in total score on the Hamilton depression scale between baseline and day 42 was associated with a one-sided p value of p1=0.037 (t=1.80, df=167). Since this p value lies between the boundaries for early rejection and acceptance, the trial was continued with a second stage. The required number of subjects was reestimated on the basis of the results of the interim analysis. The group in the second stage showed a one-sided p value of p2=0.038 (t=1.78, df=204). Therefore, the product of p values for the final combination test fell below the critical limit (0.037·0.038=0.0014<0.0038), and so the null hypothesis was rejected, and the superiority of extract WS 5570 over placebo was demonstrated for a treatment duration of 6 weeks. For the pooled data from both study stages the one-sided p value for the change in Hamilton depression score between baseline and day 42 was p=0.02 (t=2.50, df=373). For the comparisons of the two treatment groups in terms of change from baseline in Hamilton scale total score at days 28, 14, and 7, the t test results were nonsignificant. A repeated measures ANOVA with independent variables of treatment and time and an interaction term was used to compare the postbaseline Hamilton depression scores of the two treatment groups and demonstrated a significant time-by-treatment interaction (F=3.41, df=4, 1492; Greenhouse-Geisser epsilon=0.58, two-sided Greenhouse-Geisser-corrected p=0.03).

These results were confirmed in the per-protocol analysis, in which both treatment groups had the same mean decreases in Hamilton depression scale total score between baseline and day 42 as in the intention-to-treat analysis (t=2.31, df=319, p=0.02, two-sided t test).

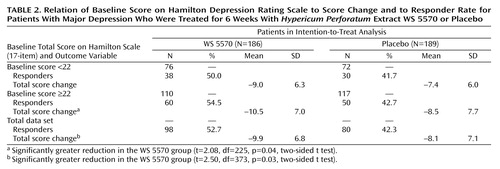

In the intention-to-treat study group, the percentage of responders (those with at least 50% decreases in Hamilton score between baseline and treatment end) was significantly higher for WS 5570 (52.7%, 98 of 186) than for placebo (42.3%, 80 of 189) (χ2=4.04, df=1, p<0.05, two-sided). Furthermore, the percentage of patients with remission (score of 6 or less on Hamilton scale at treatment end) was significantly higher for the active treatment group (24.7%, 46 of 186) than for placebo (15.9%, 30 of 189) (χ2=4.55, df=1, p=0.03, two-sided).

A secondary outcome measure was the change in total score on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale between baseline and treatment end. The mean decrease was 11.7 points (SD=9.0) for the WS 5570 group and 9.9 points (SD=9.2) for the placebo group (intention-to-treat analysis: t=1.90, df=373, p=0.06, two-sided t test). The depression subscore of the SCL-58 (11 items) showed a mean reduction of 7.9 points (SD=8.7) for the WS 5570 group and 6.5 points (SD=8.4) for the placebo group (intention-to-treat analysis: t=1.57, df=366, p=0.12, two-sided t test).

Table 2 indicates the relationship between the initial severity of depression and the magnitude of the treatment effect. Among the patients receiving WS 5570, the difference in the decrease in Hamilton depression scale total score between baseline and the final visit was larger in the subgroup of patients with initial scores equal to or above the median value of 22 points. Their decrease was significantly greater than the decrease for the patients receiving placebo (t=2.08, df=225, p=0.04, two-sided t test), but the decrease for the patients with initial Hamilton depression scores between 18 and 21 did not differ significantly from that for the placebo group (t=1.50, df=146, p=0.14, two-sided t test).

The score on the Bech melancholia subscale decreased by a mean of 5.5 points (SD=4.2) in the WS 5570 group and by 4.4 points (SD=4.1) in the placebo group (intention-to-treat analysis: t=2.60, df=373, p=0.001, two-sided t test).

Safety and Tolerability

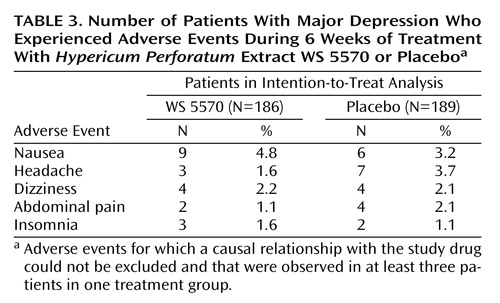

During double-blind treatment with WS 5570, 30.6% of the patients (57 of 186) experienced adverse events, compared to 37.0% (70 of 189) in the placebo group. The type, incidence (Table 3), and severity of adverse events did not indicate any treatment-emergent risks associated with WS 5570. In each study group, two patients were withdrawn prematurely because of adverse events. In the WS 5570 group, both withdrawals were necessitated by hospitalization of the patient because of symptom aggravation.

Both study drugs did not relevantly or systematically modify the biological measures assessed—neither with regard to a general trend nor on an individual patient basis.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the antidepressant efficacy of 300 t.i.d. of H. perforatum extract WS 5570, as compared to placebo, for mildly to moderately depressed patients after a treatment duration of 6 weeks.

The median difference in change in the Hamilton depression scale score between WS 5570 and placebo was 3.0 points, and the mean difference was 1.8 points. The percentage of responders in the group receiving H. perforatum was 52.7%, whereas the percentage in the placebo group was 42.3%; the difference of 10.4% was significant. This effect size is moderate, but the size of the effect observed in placebo-controlled phase III trials hardly reflects the real therapeutic potential. As observed by Montgomery (22), during recent years an increasing number of clinical trials testing the efficacy of new potential antidepressants have failed to demonstrate a difference from placebo even for established reference drugs (e.g., imipramine). The rise in placebo response rates has not been paralleled by a rise in drug response. Similar tendencies have been observed in trials for other psychiatric indications (e.g., obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, panic disorder).

Placebo-controlled phase III trials control for different sources of bias, making the therapeutic management artificial, e.g., no associated treatment in case of anxiety or insomnia, no dose adaptation depending on tolerance and efficacy. These methodological constraints are justified but likely to decrease the effect size of the active drug. On the other hand, the effect of the “therapeutic alliance” with the physician, including confidence, empathy, and helpful attitude, is increased by the awareness of the possible random assignment to a new innovative drug and the existence of weekly visits, thus increasing the placebo effect (23, 24). One of the strategies proposed to increase the difference between active drug and placebo was to recruit rather severely depressed patients (e.g., having a Hamilton depression scale score above 25), although it is not clear whether such a threshold effect is due to a limited placebo response in severely ill patients or to a mechanical effect yielding a larger difference between the evaluations before and after treatment. Therefore, the superiority observed in this study of mildly and moderately depressed patients was probably more difficult to evidence than it would have been with a group including more severely ill patients. In a recent well-designed and carefully conducted study (25), H. perforatum was compared to placebo and to a reference drug, and a significant effect was not demonstrated even for the reference compound. After reviewing the methods of the two studies, we consider only two major differences potentially relevant: our study had a small number of patients at each center, but all patients recruited were spontaneously seeking care. The difference in care-seeking behavior, reflecting a subjective perception of severity by the patient, is likely to explain the better detection of an advantage of active drug over placebo. A low dropout rate, possibly due to a low rate of adverse events during the first weeks of treatment, may have contributed to this positive result. The existence of a run-in phase was obviously of limited value, as already claimed by others (22, 26, 27). However, as suggested early on by Paykel et al. (28), we observed that severity did have an impact on outcome. The difference between treatment groups in the change from baseline in Hamilton depression score was significant for the subgroup of patients with baseline scores of 22 or higher but not for those with baseline scores less than 22, confirming the results of Laakmann et al. (10). These authors found in the H. perforatum group (extract WS 5572) responder rates of 50% for those with baseline Hamilton depression scores of 22 or higher and 49% for all patients, compared to 25% and 33%, respectively, in the placebo group.

The significant effect on the Bech melancholia subscale score and a larger effect in more severely ill patients suggest a true antidepressant effect of H. perforatum. The results observed with the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale were consistent with those of the Hamilton depression scale and shortly missed significance (p=0.06).

The duration of the study was 6 weeks because this duration was recommended for placebo-controlled phase III studies of acutely depressed patients. Greater improvement in patients receiving active drug than in those receiving placebo is commonly observed thereafter. Indeed, the improvement shown by the H. perforatum group in Figure 1 has not yet reached a plateau.

In the present trial, the two withdrawals related to adverse events in the H. perforatum group were attributable to worsening depressive symptoms due to a lack of efficacy in these particular patients, rather than to problems regarding tolerability. The herbal extract was well tolerated by all 186 patients who received it, and tolerability-related withdrawal from treatment was not indicated in a single case. Our data therefore contribute to the overall favorable safety assessment of preparations from H. perforatum extract.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the existence of an antidepressant effect of H. perforatum in mildly and moderately depressed patients.

|

|

|

Received July 26, 2001; revision received April 4, 2002; accepted March 27, 2002. From the Unité Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale 302, Hôpital Pitié Salpêtrière; the Centre Hospitalier Spécialisé en Psychiatrie de Pontorson, Pontorson, France; the Centre Hospitalier Spécialisé en Psychiatrie de La Chartreuse, Dijon, France; and the Biometrical Department, Dr. Willmar Schwabe Pharmaceuticals, Karlsruhe, Germany. Address reprint requests to Dr. Lecrubier, Unité INSERM 302, Hôpital Pitié Salpêtrière, Pavillon Clérambault, 75013 Paris, France; [email protected] (e-mail). Sponsored by Dr. Willmar Schwabe Pharmaceuticals, Karlsruhe, Germany.Hypericum Study Group: D. Arnoux, G. Aspe, J.J. Ausseill, C. Bagot, A. Benoit, P. Bern, D. Bonnaffoux, B. Bonnet Guerin, J. Charbaut, J.Y. Charlot, C. Claden, G. Clerc, H. de Verbigier, R. Didi, M. Faure, F. Gheysen, S. Guibert, P. Khalifa, P. Le Goubey, D. Liegaut, Y. Mouhot, A. Pargade Moradell, L. Rochard, G. Saint Mard, H. Sauret, and J.R. Zekri.

Figure 1. Change in Score on Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in Patients With Major Depression During 6 Weeks of Treatment With Hypericum Perforatum Extract WS 5570 or Placebo

1. Kim HL, Streltzer J, Goebert D: St John’s wort for depression—a meta-analysis of well-defined clinical trials. J Nerv Ment Dis 1999; 187:532-539Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Linde K, Ramirez G, Mulrow CD, Pauls A, Weidenhammer W, Melchart D: St John’s wort for depression—an overview and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Br Med J 1996; 313:253-258Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Volz HP: Controlled clinical trials of Hypericum extracts in depressed patients—an overview. Pharmacopsychiatry 1997; 30(suppl 2):72-76Google Scholar

4. Ernst E: St John’s wort, an anti-depressant? a systematic, criteria-based review. Phytomedicine 1995; 2:67-71Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. De Smet PAGM, Nolen WA: St John’s wort as an antidepressant. Br Med J 1996; 313:241-242Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Ernst E, Rand JI, Barnes J, Stevinson C: Adverse effects profile of the herbal antidepressant St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum L). Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1998; 54:589-594Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Deltito J, Beyer D: The scientific, quasi-scientific and popular literature on the use of St John’s wort in the treatment of depression. J Affect Disord 1998; 51:345-351Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56-62Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278-296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Laakmann G, Dienel A, Kieser M: Clinical significance of hyperforin for the efficacy of Hypericum extracts on depressive disorders of different severities. Phytomedicine 1998; 5:435-442Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Bech P, Gram LF, Dein E, Jacobsen O, Vitger J, Bowling TG: Quantitative rating of depressive states. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1975; 51:161-170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Lecrubier Y, Sheehan DV, Weiller E, Amorim P, Bonara I, Sheehan KH, Janavs J, Dunbar GC: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), a short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur Psychiatry 1997; 12:224-231Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59(suppl 20):22-33Google Scholar

14. Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products: Note for Guidance on Clinical Investigation of Medicinal Products in the Treatment of Depression (draft). London, EMEA: The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, 2001Google Scholar

15. Hedlund JL, Vieweg BW: The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: a comprehensive review. J Operational Psychiatry 1979; 10:149-165Google Scholar

16. Montgomery SA, Åsberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 134:382-389Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Guelfi JD, Barthelet G, Lancrenon S, Fermanian J: Structure factorielle de la HSCL: sur un échantillon de patients anxio-dépressifs français. Ann Med Psychol 1984; 142:889-896Medline, Google Scholar

18. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218-222Google Scholar

19. Bauer P, Koehne K: Evaluation of experiments with adaptive interim analyses. Biometrics 1994; 50:1029-1041Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. International Conference on Harmonization: Note for Guidance on Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials: ICH Topic E9. London, EMEA: The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, 1998Google Scholar

21. Kieser M, Bauer P, Lehmacher W: Inference on multiple endpoints in clinical trials with adaptive interim analyses. Biometrical J 1999; 41:261-277Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Montgomery SA: The failure of placebo-controlled studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1999; 9:271-276Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Montgomery SA: Alternatives to placebo-controlled trials in psychiatry. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 1999; 9:265-269Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Schweizer E, Rickels K: Placebo response in generalized anxiety: its effect on the outcome of clinical trials. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58(suppl 11):30-38Google Scholar

25. Davidson J: The NIH Hypericum study in depression, in Proceedings of the 40th Annual Congress of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. Nashville, Tenn, ACNP, 2001, p 23Google Scholar

26. Greenberg RP, Fisher S, Riter JA: Placebo washout is not a meaningful part of antidepressant drug trials. Percept Mot Skills 1995; 81:688-690Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Bialik RJ, Ravindran AV, Bakish D, Lapierre YD: A comparison of placebo responders and nonresponders in subgroups of depressive disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci 1995; 20:265-270Medline, Google Scholar

28. Paykel ES, Hollyman JA, Freeling P, Sedgewick P: Predictors of therapeutic benefit from amitriptyline in mild depression: a general practice placebo-controlled trial. J Affect Disord 1988; 14:83-95Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar