A Placebo-Controlled Study of Fluoxetine in Continued Treatment of Bulimia Nervosa After Successful Acute Fluoxetine Treatment

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The efficacy of fluoxetine in the acute management of bulimia nervosa is well established; however, few controlled studies have examined whether continuation of pharmacotherapy provides protection from relapse. This study compared the efficacy and safety of treatment with fluoxetine versus placebo in preventing relapse of bulimia nervosa during a 52-week period after successful acute fluoxetine therapy. METHOD: Patients who met DSM-IV criteria for bulimia nervosa, purging type, were assigned to single-blind treatment with 60 mg/day of fluoxetine. After 8 weeks of treatment, patients were considered responders if they experienced a decrease ≥50% from baseline in the frequency of vomiting episodes during 1 of the 2 preceding weeks. Responders were randomly assigned to receive 60 mg/day of fluoxetine or placebo and were monitored for relapse for up to 52 weeks. Patients met relapse criteria if they experienced a return to the baseline vomiting frequency that persisted for 2 consecutive weeks. RESULTS: Of the 232 patients who entered the acute phase, 150 patients (65%) met response criteria and were randomly assigned to receive fluoxetine (N=76) or placebo (N=74). Fluoxetine-treated patients exhibited a longer time to relapse than placebo-treated patients. Quantitative analysis of other efficacy measures, including frequency of vomiting episodes, frequency of binge eating episodes, Clinical Global Impression severity and improvement scores, the patient’s global impression score, and Yale-Brown-Cornell Eating Disorder Scale score, indicated that the efficacy of fluoxetine treatment was statistically superior, compared to placebo. There were no clinically relevant differences in safety between groups. Attrition in this study was high, especially in the first 3 months after random assignment to treatment groups. CONCLUSIONS: Continued treatment with fluoxetine in patients with bulimia nervosa who responded to acute treatment with fluoxetine improved outcome and decreased the likelihood of relapse.

Bulimia nervosa, characterized by uncontrolled binge-eating and self-induced purging or other compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain, is associated with substantial rates of psychiatric and medical comorbidity (1). Its lifetime prevalence is estimated to be as high as 2.8% (2). Although the causal mechanisms underlying bulimia nervosa are not completely understood, evidence suggests that it is associated with abnormalities in central serotonergic function. Women with bulimia nervosa have a blunted prolactin response and a normal cortisol response to the postsynaptic serotonergic agonist m-chlorophenylpiperazine given orally and to the serotonin precursor l-tryptophan given intravenously, suggesting alteration of receptor activity at or above the hypothalamus (3). A blunted prolactin response to fenfluramine has also been demonstrated (4). Since satiety in response to food intake is mediated in part by serotonergic input to the ventromedial hypothalamus, a defect in serotonin function may produce impaired recognition of satiety, thus contributing to binge eating (5).

A number of antidepressants have been effective in the short-term treatment of bulimia nervosa. Overall, medication treatment decreases binge frequency by an average of 56%, compared with an average decrease of 11% with placebo treatment (6). Decreases in the frequency of self-induced vomiting appear to be similar. Tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, bupropion, and trazodone have all been shown to be therapeutically superior to placebo (7–16). Fluoxetine has proven to be effective in reducing bulimic symptoms in two 8-week double-blind trials (17, 18) and in one longer term, 16-week double-blind trial (19).

Fewer data are available regarding the long-term efficacy of pharmacotherapy, as well as its impact on relapse prevention. Uncontrolled follow-up studies have suggested that patients with bulimia nervosa often remain symptomatic for 4–6 years, although they may maintain improvements achieved during treatment (6). A review of eight studies with follow-up periods of 6 months to 6 years showed that approximately one-third of the patients who improved acutely experienced a resurgence of bulimic symptoms. The probability of relapse appears to be highest during the first year after recovery, with the risk declining after 4 years (20).

The present study was designed to prospectively evaluate the efficacy and safety of treatment with fluoxetine versus placebo in preventing relapse of bulimia nervosa over a 52-week double-blind treatment period after response to acute fluoxetine treatment.

Method

Study Population

The study was conducted at 16 sites in the United States. All investigators were psychiatrists or physicians specializing in psychiatry. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each site. Patients’ participation in the study was voluntary, and all patients gave written informed consent before enrollment.

The study population included male and female outpatients, at least 18 years old, with a psychiatric diagnosis of bulimia nervosa, purging type, as defined by the DSM-IV criteria. Purging must have included self-induced vomiting. Patients were excluded if they had participated in a prior fluoxetine study or taken fluoxetine within 5 weeks before enrollment or if they had been previously treated with 60 mg/day of fluoxetine for longer than 8 weeks. Patients were excluded if they had coexisting schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, mood-congruent or mood-incongruent psychotic features, serious suicidal risk, organic brain disease, a history of seizures, a medically unstable condition, or a history of an alcohol and/or other substance abuse disorder within 3 months before enrollment. Patients who had used a monoamine oxidase inhibitor within 2 weeks before enrollment or had used other investigational drugs or psychoactive medications within 4 weeks before enrollment were excluded. Patients who had received cognitive behavior therapy within 4 weeks of enrollment or who planned to begin a structured, focused therapy at any time during the study were excluded.

Study Design

After a 1-week no-therapy screening phase, patients who continued to meet entry criteria were assigned to single-blind treatment with 60 mg/day of fluoxetine. Dosage adjustment, at the clinician’s discretion, was allowed during the first 2 weeks of treatment to accommodate patients who were initially unable to tolerate 60 mg/day of fluoxetine. After 8 weeks of acute treatment, responders were randomly assigned to receive 60 mg/day of fluoxetine or placebo for up to 52 weeks. Nonresponders and patients who were unable to tolerate a dose of 60 mg/day were discontinued from the study.

Study medication was packaged in blister packs and contained either 20-mg fluoxetine capsules or matching placebo capsules. At each visit, the patient returned the blister packs so that the remaining capsules could be counted. Patients who missed their medication for 5 consecutive days or who failed to attend visits within the stated periods were deemed noncompliant and were withdrawn from the study. The treatment group to which the patient was assigned was determined by a computer-generated randomization sequence. No one at the study site had access to the study randomization list. Emergency labels, generated by a computer drug-labeling system, were available to the investigator. These labels, which revealed the patient’s treatment group, were opened only if the choice of follow-up treatment depended on the patient’s therapy assignment or in medical emergencies.

Study Procedures

During the screening phase and the 8-week single-blind acute therapy phase, patients were seen by the investigators each week. During the 52-week, double-blind therapy period, visits occurred at 2-week intervals during the first 8 weeks and at 4-week intervals thereafter.

Efficacy was measured by the change in the number of vomiting and binge-eating episodes per week and by ratings on the Eating Disorder Inventory (21), Yale-Brown-Cornell Eating Disorder Scale (22), and Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity and improvement scales (23) and by the patient’s global impression, which uses a 7-point scale identical to the Clinical Global Impression improvement scale. The 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (24) was used to measure the presence and severity of depression. Information about bulimic behaviors was obtained by using a daily diary in which patients recorded their episodes of binge eating, vomiting, and other purging behaviors.

The CGI severity measure was obtained at the beginning of acute therapy (visit 2). The Eating Disorder Inventory, Yale-Brown-Cornell Eating Disorder Scale, CGI improvement scale, the patient’s global impression, and Hamilton depression scale were completed at the beginning of acute therapy (visit 2), at the end of acute therapy (visit 10), and at 4-week intervals throughout the double-blind relapse-prevention period. The patients’ diaries were collected at each visit. Data on adverse events were collected by open-ended questioning about general well-being and problems with medication and were recorded at each visit regardless of the perceived relationship to therapy.

Statistical Analyses

The primary efficacy measure was the change in the number of vomiting episodes per week. This measure was also used to determine the patient’s eligibility for continuation into the double-blind therapy period and to assess relapse during the double-blind period. To be designated a treatment responder at the end of the acute therapy period, patients must have experienced a decrease of ≥50% in the frequency of vomiting episodes during at least 1 of the 2 preceding weeks, compared to the baseline (screening) week. Patients were considered relapsers during the double-blind period if they experienced a return to the baseline frequency of vomiting for 2 consecutive weeks. For ethical reasons, patients who experienced a return to the baseline frequency of vomiting for a single week and whose condition had deteriorated significantly could also be designated as relapsers at the clinician’s discretion.

Time-to-relapse curves were estimated for each treatment group by using the product-limit (Kaplan-Meier) method for the data for all patients with at least one postrandomization measurement. A two-sided log-rank test was used to compare the time-to-relapse distributions. Confidence limits for estimated cumulative relapse rates were constructed for the 3- , 5- , and 12-month time points by using Greenwood’s estimate of the variance (25), and the difference in estimated relapse rates was tested at these time points by using the proportions test proposed by Gray and Tsiatis (26). In addition, a Cox proportional hazards model stratified by investigative site was used to assess the relationship between baseline covariates (frequency of vomiting and binge eating) and time to relapse.

Endpoint analysis of continuous efficacy and safety data (vital signs and laboratory data) evaluated change from randomization to the last visit in the postrandomization period (last observation carried forward). An analysis of variance model with treatment, investigator, and the treatment-by-investigator interaction was used to compute the summary statistics for normally distributed measurements. A rank-transformed nonparametric model proposed by Akritas et al. (27) was used for measurements that failed the normal assumption. Data from three sites with two or fewer patients per treatment group were pooled together for the analysis of continuous efficacy and safety.

Data on patients’ characteristics were summarized at baseline and at random assignment to the treatment groups. Treatment differences were assessed with Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Student’s t test for continuous variables. Reasons for discontinuation from the study and adverse events that first occurred or worsened during double-blind therapy were compared between treatment groups by using Fisher’s exact test.

Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

Acute Response

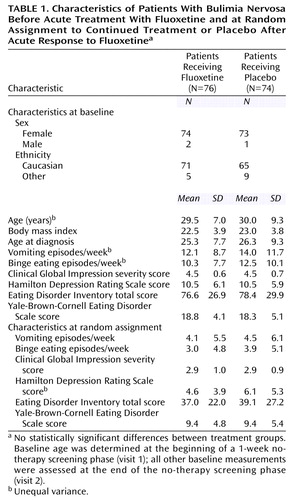

Of the 265 patients who participated in psychological and physical screening, 33 did not meet entry criteria and were excluded. Of the 232 patients who received single-blind acute therapy, 150 patients (64.7%) met response criteria and were randomly assigned to double-blind therapy. The treatment groups were comparable at baseline with respect to age, gender, race, body mass index, and severity of illness. At random assignment to treatment groups, the patients’ severity of illness was comparable. The majority of the patients were women and Caucasian (Table 1).

Of the 232 patients who received single-blind acute therapy, 94 patients (40.5%) had comorbid depression (Hamilton depression scale total ≥12). There was no significant difference in response rates between depressed and nondepressed patients (62.8% versus 65.7%) (χ2=0.21, df=1, p=0.65). Of the 232 patients who received single-blind acute therapy, 41 patients (17.7%) had complete remission of symptoms, that is, no vomiting episodes during the final week of acute therapy.

Time to Relapse

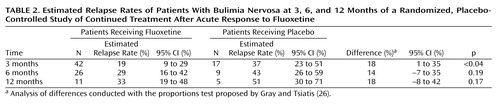

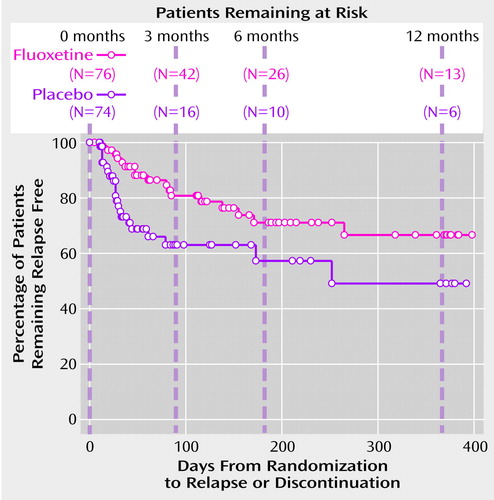

The primary hypothesis, that fluoxetine treatment prolongs the time to relapse, was assessed by a log-rank test applied to the Kaplan-Meier survival function. The test was statistically significant (χ2=5.79, df=1, p<0.02). The survival curve shows that most of the relapses among placebo-treated patients occurred during the first 3 months after randomization (Figure 1). Compared with the placebo group, the fluoxetine-treated group had a lower number of relapses during the first 3 months and a more gradually decreasing probability of remaining relapse free (Figure 1). The estimated relapse rates and differences in relapse rates (the rate for the placebo group minus the rate for the fluoxetine group) were computed at 3- , 6- , and 12-month time points (Table 2). The difference in relapse rates was statistically significant at the 3-month time point and remained approximately constant from 3–12 months, although the difference was not statistically significant at the 6- and 12-month time points because of the high attrition rate in the study. The Cox proportional hazards model indicated that the relapse rate did not depend on the baseline frequency of vomiting or binge eating.

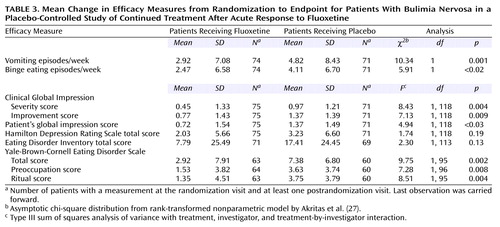

Endpoint Analysis of Change in Efficacy Measures

Analysis of mean change in efficacy measures from randomization to endpoint shows that both the fluoxetine-treated group and the placebo-treated group worsened over time in each measure. However, statistically significant differences favoring fluoxetine were observed for vomiting episodes, binge-eating episodes, CGI severity score, CGI improvement score, patient’s global impression score, and Yale-Brown-Cornell Eating Disorder Scale total score, including statistically significant differences in both the preoccupation and ritual subtotals (Table 3).

Safety

Adverse events that were first reported or that worsened during double-blind therapy were compared between treatment groups. The only event with a statistically significant difference in frequency between groups was rhinitis (31.6% for the fluoxetine group, compared to 16.2% for the placebo group) (p<0.04, Fisher’s exact test). The rate of discontinuation because of an adverse event was also similar between treatment groups, and the only adverse event leading to discontinuation in ≥2% of patients was unintended pregnancy (2.6% for the fluoxetine group, compared to 4.1% for the placebo group).

There were no statistically significant differences between groups in change from randomization to endpoint for systolic or diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, or weight. Although there were statistically significant differences in mean changes in certain laboratory analytes from baseline to endpoint (magnesium, bicarbonate, and urine pH; all with a negative change in the fluoxetine-treated group and a positive change in the placebo-treated group), the mean endpoint values were not indicative of drug-related toxicity.

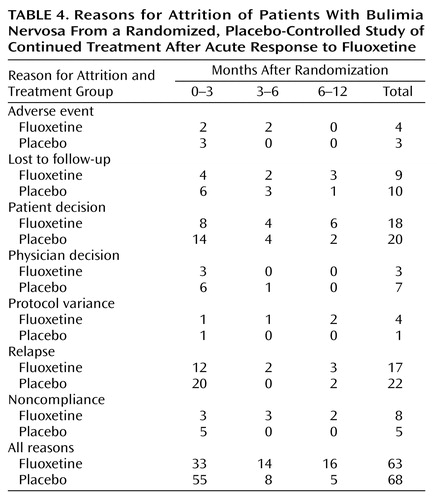

Reasons for discontinuation were analyzed by time intervals after randomization (0–3 months, 3–6 months, and 6–12 months) (Table 4). Although the overall number of patients who discontinued for various reasons was similar among treatment groups, there were some interesting trends that appeared to be time-related. In the first 3 months of the study, a large number of patients (11 fluoxetine-treated patients and 20 placebo-treated patients) discontinued for reasons of either patient decision or physician decision. Further inspection of individual study comments for these patients revealed that eight fluoxetine-treated patients and 15 placebo-treated patients appeared to discontinue because of poorer than expected efficacy in this time period. None of these patients met the a priori relapse criteria and were considered censored in the time-to-relapse analysis.

Relapse as a reason for discontinuation occurred in 17 fluoxetine-treated patients and 22 placebo-treated patients. Within the fluoxetine-treated group, there was no significant difference in relapse rates between depressed and nondepressed patients (24.1% versus 21.2%) (χ2=0.09, df=1, p=0.77).

Discussion

The results of the single-blind therapy phase confirm the efficacy of fluoxetine in the acute management of bulimia nervosa, with the response rate of 64.7% consistent with previous reports (6). The remission rate of 17.7% is also consistent with literature reports, which cite low abstinence rates during acute therapy (28). The comparable response rates among depressed patients and nondepressed patients (62.8% versus 65.7%) further suggest that the absence or presence of comorbid depression does not affect response in patients with bulimia nervosa, consistent with results reported in a previous multicenter study (18).

During 52 weeks of double-blind relapse prevention monitoring, patients who were randomly assigned to continued treatment with fluoxetine had a significantly longer time to relapse than patients who received placebo. Analyses of mean change from randomization to endpoint for each primary and secondary efficacy measure provided further evidence of the beneficial effect of fluoxetine. Within the group randomly assigned to continued fluoxetine treatment, the comparable relapse rates among depressed patients and nondepressed patients (24.1% versus 21.2%) suggest that comorbid depression is not a predictor of relapse among responders to acute treatment for bulimia nervosa.

The majority of patients who received placebo relapsed within the first 3 months after randomization, in contrast to the more gradual loss of fluoxetine-treated patients due to relapse during the course of the trial. This finding suggests that there may be a subgroup of pharmacologically responsive bulimic patients who are highly sensitive to medication discontinuation. Future research may help elucidate traits of this subgroup and potentially determine clinical strategies. It is noteworthy that the pharmacokinetic profile of fluoxetine and norfluoxetine, its active metabolite, parallels this observed pattern of relapse, as approximately 5–6 weeks are required for drug clearance.

To our knowledge, the present study is the largest placebo-controlled, double-blind trial evaluating relapse prevention associated with maintenance pharmacotherapy for bulimia nervosa. However, the study had several limitations. This study utilized patient diaries to assess the primary outcome variable of weekly episodes of vomiting. Although no independent method to assess the reliability of these self-reports was used, one would expect equal distribution of unreliable measures across treatment groups. It is important to note that vomiting is reported with greater clarity than is binge eating, the latter tending to be assessed more variably by patients. Although limited by the accuracy and veracity of self-report, and in light of the absence of a more objective index of measurement, this method of recording is an improvement over retrospective account. Patient diaries have been used extensively in studies assessing bulimia nervosa, including the large multicenter fluoxetine trial referenced earlier (18).

Determining operational definitions of response and relapse in bulimia nervosa trials represents a challenge, and efforts in this area may be viewed as evolving. On the basis of the results of the large multicenter trial (18), which reported a median reduction of 56% in weekly vomiting episodes in the group who received 60 mg/day of fluoxetine and which calculated response as ≥50% improvement in weekly vomiting episodes, a reduction of at least 50% was felt to represent a clinically meaningful improvement to a single treatment intervention. Similarly, a sustained return to the frequency of vomiting experienced at the time of acute study entry was considered an appropriate criterion for relapse. Clearly, the definition of response used in this study allows for persistence of symptoms, even for the maintenance of syndromal criteria by some patients. However, considering the negative consequences, both psychological and medical, of persistent bulimic behavior, a 50% reduction in frequency of vomiting episodes benefits clinical status.

Attrition during the relapse prevention phase of the trial was high in both treatment groups, although there was a trend for more fluoxetine-treated patients to complete the protocol. The largest amount of patient attrition occurred in the first 3 months after randomization. Relapse, patients’ decisions, and physicians’ decisions were the most common reasons for discontinuation. Investigators’ study notes for the patients who discontinued participation because of the patient’s decision or the physician’s decision revealed that eight of the fluoxetine-treated patients and 15 of the placebo-treated patients were discontinued for worsening disease condition. None of these patients met the formal relapse criteria and were therefore considered as censored observations in the time-to-relapse analysis. It is important to note, even in light of the large attrition rate, that the estimated difference in relapse rates at 1 year was virtually the same as the estimated difference after 3 months. This finding indicates that the observed benefit of fluoxetine treatment occurs in the first 3 months and that this cumulative benefit remains constant after this time period. As clinical experience underscores the difficulty of maintaining patients with bulimia in longer-term therapy, the extended period in which fluoxetine-treated patients remained in the study, even in light of the noted attrition rate, suggests the benefit of continued treatment.

Although fluoxetine treatment was associated with a significantly lower rate of relapse, there was worsening over time on all measures of efficacy, reflecting symptomatic regression. This finding suggests that fluoxetine alone may not be an adequate treatment after acute response in most patients and that additional management strategies may be required to augment or to sustain initial improvement. Several studies have addressed the utility of combined approaches in an effort to establish effective treatment regimens (17, 29–32). Fichter and associates (17), Goldbloom and associates (29), and Mitchell and associates (30) were unable to show greater improvement with the combination of pharmacologic therapy and counseling than with counseling alone. Agras and associates (31) studied 71 patients randomly allocated to treatment with desipramine, cognitive behavior therapy, and a combination of the two interventions. At 16 weeks, both cognitive behavior therapy and combined therapy were superior to medication alone in reducing binge-eating and purging. Continuing cognitive behavior therapy appeared to prevent relapse for up to 72 weeks in the patients who discontinued medication treatment. In addition, 77% of the patients with combined therapy achieved abstinence from binge eating and purging, compared with 54% of those receiving cognitive behavior therapy alone. Walsh and associates (32), in a placebo-controlled study of 120 women, found that cognitive behavior therapy plus medication (desipramine followed by fluoxetine if the desipramine was poorly tolerated or ineffective) was superior to medication alone in reducing binge eating and vomiting, but supportive psychotherapy plus medication was not. Mitchell and associates (30), in a review of controlled trials of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in the treatment of bulimia nervosa, hypothesized that a longer course of pharmacologic therapy in combination with counseling would be of greatest benefit. Given the high attrition rate observed in this fluoxetine trial and the known benefits of cognitive behavior therapy, the latter should play a primary role in both acute and continuation treatment of patients with bulimia.

To our knowledge, the current study represents the largest relapse prevention trial to date assessing a pharmacotherapy treatment for bulimia nervosa. This study demonstrated that continued treatment with fluoxetine in patients who responded to acute therapy was well tolerated and associated with a significant reduction in the likelihood of relapse during a 52-week monitoring period. An important finding, which is consistent with clinical experience and reported research results, was the gradual worsening of symptom severity in both the fluoxetine-treated and placebo-treated groups. Although fluoxetine treatment was statistically and clinically superior to placebo treatment in multiple measures of outcome, the latter observation suggests the benefit of a multimodal approach. Additional outcome data on the long-term benefits of combined therapeutic approaches in improving the likelihood of sustaining initial gains and in reducing the rate of relapse should influence future treatment guidelines. The findings of this study suggest that clinicians should consider providing acute responders to fluoxetine with maintenance fluoxetine treatment for up to 1 year, with psychotherapeutic interventions implemented on the basis of individual need.

Acknowledgments

This study was completed with the participation of the following investigators: Anne Becker, M.D., Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Barton Blinder, M.D., Ph.D., Newport Beach, Calif.; Harry Brandt, M.D., Center for Eating Disorders, Towson, Md.; Lynn Cunningham, M.D., Vine Street Clinical Research, Springfield, Ill.; Brenda Erikson, M.D., University of New Mexico, Albuquerque; James Ferguson, M.D., Pharmacology Research Corporation, Salt Lake City; Tana Grady, M.D., Duke University, Durham, N.C.; Harry Gwirtsman, M.D., Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.; James Hudson, M.D., McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass.; Walter Kaye, M.D., University of Pittsburgh Western Psychiatric Institute, Pittsburgh; John Lauriello, M.D., University of New Mexico, Albuquerque; Russell Marx, M.D., San Luis Rey Hospital, Encinitas, Calif.; Pauline Powers, M.D., University of South Florida College of Medicine, Tampa; Jeffrey Simon, M.D., Northbrooke Research Center, Brown Deer, Wis.; B. Timothy Walsh, M.D., New York Psychiatric Institute, New York; and Kathyrn Zerbe, M.D., Menninger Clinic, Topeka, Kan.

|

|

|

|

Presented in part at the 11th Congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Oct. 31–Nov. 4, 1998, Paris, and the 37th annual meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Dec. 14–18, 1998, Las Croabas, Puerto Rico. Received Feb. 1, 2001; revision received June 4, 2001; accepted July 31, 2001. From Pfizer Inc, New York; Weill Medical College of Cornell University, White Plains, NY; Lilly Research Laboratories, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis; and Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland. Address reprint requests to Ms. Koke, Lilly Research Laboratories, Lilly Corporate Center 2200, Indianapolis, IN 46285; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by a clinical research grant from Eli Lilly and Company. The authors thank Roy Tamura of Eli Lilly and Company for statistical assistance.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of the Percentage of Patients With Bulimia Nervosa Remaining Relapse Free in a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study of Continued Treatment After Acute Response to Fluoxetinea

aTwo-sided log-rank test applied to the Kaplan-Meier survival function (χ2=5.79, df=1, p<0.02).

1. Herzog DB, Nussbaum KM, Marmor AK: Comorbidity and outcome in eating disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1996; 19:843-859Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kendler KS, MacLean C, Neale M, Kessler R, Heath A, Eaves L: The genetic epidemiology of bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:1627-1637Link, Google Scholar

3. Brewerton TD, Mueller EA, Lesem MD, Brandt HA, Quearry B, George DT, Murphy DL, Jimerson DC: Neuroendocrine responses to m-chlorophenylpiperazine and l-tryptophan in bulimia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:852-861Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. McBride PA, Anderson GM, Khait VD, Sunday SR, Halmi KA: Serotonergic responsivity in eating disorders. Psychopharmacol Bull 1991; 27:365-372Medline, Google Scholar

5. Leibowitz SF: The role of serotonin in eating disorders. Drugs 1990; 39(suppl 3):33-48Google Scholar

6. Jimerson DC, Herzog DB: Pharmacologic approaches in the treatment of eating disorders. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1993; 1:82-93Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI, Jonas JM, Yurgelun-Todd D: Bulimia treated with imipramine: a placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:554-558Link, Google Scholar

8. Hughes PL, Wells LA, Cunningham CJ, Ilstrup DM: Treating bulimia with desipramine: a placebo-controlled double-blind study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:182-186Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Agras WS, Dorian BG, Kirkley BG, Arnow B, Bachman J: Imipramine in the treatment of bulimia: a double-blind controlled study. Int J Eat Disord 1987; 6:29-38Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Kaplan AS, Garfinkel PE, Garner DM: Bulimia treated with carbamazepine and imipramine, in 1987 Annual Meeting New Research Program. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987, p 127Google Scholar

11. Price WA, Babai MR: Antidepressant drug therapy for bulimia: current status revisited (letter). J Clin Psychiatry 1987; 48:385Medline, Google Scholar

12. Barlow J, Blouin J, Blouin A, Perez E: Treatment of bulimia with desipramine: a double-blind crossover study. Can J Psychiatry 1988; 33:129-133Medline, Google Scholar

13. Horne RL, Ferguson JM, Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI, Lineberry CG, Ascher J, Cato A: Treatment of bulimia with bupropion: a multicenter controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 1988; 49:262-266Medline, Google Scholar

14. Walsh BT, Gladis M, Rose SP, Stewart JW, Stetner F, Glassman AH: Phenelzine vs placebo in 50 patients with bulimia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:471-475Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Kennedy SH, Piran N, Warsh JJ, Prendergast P, Mainprize E, Whynot C, Garfinkel PE: A trial of isocarboxazid in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1988; 8:391-396Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Pope HG Jr, Keck PE Jr, McElroy SM, Hudson JI: A placebo-controlled study of trazodone in bulimia nervosa. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1989; 9:254-259Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Fichter MM, Leibl K, Rief W, Brunner E, Schmidt-Auberger S, Engel RR: Fluoxetine versus placebo: a double-blind study with bulimic inpatients undergoing intensive psychotherapy. Pharmacopsychiatry 1991; 24:1-7Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Fluoxetine Bulimia Nervosa Collaborative Study Group: Fluoxetine in the treatment of bulimia nervosa: a multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:139-147Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Goldstein DJ, Wilson MG, Thompson VL, Potvin JH, Rampey AH (Fluoxetine Bulimia Nervosa Research Group): Long-term fluoxetine treatment of bulimia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry 1995; 166:660-666Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Keel PK, Mitchell JE: Outcome in bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:313-321Link, Google Scholar

21. Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Polivy J: Eating Disorder Inventory. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1983Google Scholar

22. Mazure CM, Halmi KA, Sunday SR, Romano SJ, Einhorn AM: The Yale-Brown-Cornell Eating Disorder Scale: development, use, reliability, and validity. J Psychiatr Res 1994; 28:425-445Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 218-222Google Scholar

24. Hamilton M: Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1967; 6:278-296Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Greenwood M: The Natural Duration of Cancer: Reports on Public Health and Medical Subjects 33. London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1926, pp 1-26Google Scholar

26. Gray RJ, Tsiatis AA: A linear rank test for use when the main interest is in difference in cure rates. Biometrics 1989; 45:899-904Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Akritas MG, Arnold SF, Brunner E: Nonparametric hypotheses and rank statistics for unbalanced factorial designs. J Am Statistical Assoc 1997; 92:258-265Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Mitchell JE, Raymond N, Specker S: A review of the controlled trials of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 1993; 14:229-247Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Goldbloom DS, Olmsted M, Davis R, Clewes J, Heinmaa M, Rockert W, Shaw B: A randomized controlled trial of fluoxetine and cognitive behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa: short-term outcome. Behav Res Ther 1997; 35:803-811Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Mitchell JE, Pyle RL, Eckert ED, Hatsukami D, Pomeroy C, Zimmerman R: Comparison study of antidepressants and structured intensive group psychotherapy in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:149-157Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Agras WS, Rossiter EM, Arnow B, Schneider JA, Telch CF, Raeburn SD, Bruce B, Perl M, Koran LM: Pharmacologic and cognitive-behavioral treatment for bulimia nervosa: a controlled comparison. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:82-87Link, Google Scholar

32. Walsh BT, Wilson GT, Loeb KL, Devlin MJ, Pike KM, Roose SP, Fleiss J, Waternaux C: Medication and psychotherapy in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:523-531Link, Google Scholar