Male Criminals With Organic Brain Syndrome: Two Distinct Types Based on Age at First Arrest

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined whether criminals with organic brain syndrome could be divided into two distinct types. The authors proposed that early starters (onset of criminal activity by age 18) would display a persistent, long-lasting pattern of deviance that was largely independent of their brain disorder, whereas late starters (onset at age 19 or after) would exhibit deviant behaviors that began late in life and were more directly related to their brain disorder. METHOD: Subjects were 1,130 male criminal offenders drawn from a birth cohort of all individuals born between January 1, 1944, and December 31, 1947, in Denmark. The main study group included all men with both a history of criminal arrest and a hospitalization for organic brain syndrome (N=565). In addition, for a subset of analyses, the authors examined a randomly selected, same-size comparison group of men with a history of criminal arrest who were not hospitalized for organic brain syndrome. Data were available on all arrests and all psychiatric hospitalizations for individuals in this cohort through the age of 44. RESULTS: Among those with organic brain syndrome, early starters were significantly more likely than late starters to 1) be arrested before the onset of organic brain syndrome, 2) show a higher rate of offending before but not after the onset of organic brain syndrome, 3) be both recidivists and violent recidivists, and 4) have a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder. CONCLUSIONS: Male criminals with organic brain syndrome can be meaningfully divided into two distinct types on the basis of age at first arrest. Early starters show a more global, persistent, and stable pattern of offending than late starters. These results have implications for treatment and risk assessment.

Several large cohort studies have found an association between crime and major mental disorders. For example, Hodgins (1) examined the criminal and mental health records of a Swedish birth cohort that was followed up to the age of 30. Mentally ill men were 2.5 times more likely to be registered for a criminal offense than same-sex comparison subjects. Similarly, mentally ill women were four times more likely to be registered for a criminal offense than same-sex comparison subjects. Another large cohort study found that men and women who had been in a psychiatric hospital were convicted for significantly more crimes than their nonhospitalized peers (2).

Several studies have examined the relationship between crime and specific psychiatric disorders (2, 3). One such disorder is organic brain syndrome. Per ICD-8, organic brain syndrome is a persistent impairment of comprehension caused by dementia, delirium, infection, injury, or substance-induced psychosis. Previous studies of organic brain syndrome and crime or aggression have either used hospital records to determine the psychiatric diagnoses of criminal offenders or used criminal records to determine the offense history of mentally ill individuals. For example, Tardiff and Sweillam (4) analyzed the records of 9,365 patients admitted to public hospitals in 1974. Results showed higher rates of assaultive behavior among patients with a DSM-II diagnosis of organic brain syndrome. (The DSM-II definition of organic brain syndrome closely parallels the ICD-8 definition. Specifically, DSM-II defines organic brain syndrome as a psychological or behavioral abnormality associated with transient or permanent dysfunction of the brain [e.g., delirium or dementia].) In another study, Travin et al. (5) found that one-half of the violent patients in a psychiatric consultation service had been diagnosed with organic brain syndrome. Other studies have found higher rates of organic brain syndrome among indicted criminals (6) and violent recidivists (7). These findings suggest that patients with organic brain syndrome present a significant risk of violence for staff and other patients in clinical settings.

While many studies have suggested an association between organic brain syndrome and crime, very few have explored this relationship in depth. In fact, most data regarding organic brain syndrome and violence are drawn from broad, general investigations of crime and mental illness (2, 3). Unfortunately, the percentage of patients with organic brain syndrome in these studies is often very small. In addition, these studies rarely break down demographic data by diagnosis or examine comorbid conditions. Thus, it is difficult to know whether organic brain syndrome is associated with a particular pattern of demographic characteristics or comorbid diagnoses. This may be especially problematic given recent evidence that suggests that the relationship between organic brain syndrome and violence is mediated by specific demographic and diagnostic variables. For example, a previous examination of the cohort that is the focus of the current study found that the relationship between organic brain syndrome and violence was no longer significant for female subjects after control for socioeconomic status, marital status, secondary substance abuse, and secondary personality disorders together (8).

A second weakness of previous organic brain syndrome research is its common reliance on single hospital samples (6, 7). Psychiatric wards show marked variation in their policies for dealing with violent behavior and in the frequency with which violence occurs. Thus, the violence that occurs for individuals in any single hospital ward may not be representative of the violence that occurs within the general population of organic brain syndrome offenders.

A final weakness of previous organic brain syndrome research is related to causal assumptions. Most organic brain syndrome studies assume that brain disorder precedes and causes criminal behavior (6). These studies paint a picture of normal, law-abiding individuals, who, at some point in life, develop organic brain syndrome and begin committing crimes. This temporal sequence, however, has not been validated. For example, Leygraf (9) found that 52% of the organic brain syndrome patients in West German forensic hospitals committed their first crime before being diagnosed with organic psychosis. Thus, while organic brain syndrome may lead some individuals to commit crimes, others display antisocial behavior long before they become ill. Furthermore, certain types of antisocial behavior, such as excessive drug and alcohol use, reckless driving, and fighting may actually produce brain damage. In these cases, organic brain syndrome is not the cause of criminal behavior but rather the consequence of a long-standing pattern of deviance.

Hodgins et al. (10) delineated two types of mentally ill criminal offenders: early and late starters. Early starters display a long-lasting pattern of antisocial behavior that begins well before the onset of mental illness. This pattern includes poor academic performance, conduct problems, criminal offending, substance abuse, and antisocial personality disorder. For early starters, mental illness is simply an addition to an established pattern of deviance. In contrast, late starters show no evidence of criminal behavior before the onset of their illness. For late starters, mental illness seems to play a more causal role in criminal offending. For example, mental illness may cause impulsiveness or delusions that, in turn, lead to criminal behavior. Support for this two-type model comes from studies of male offenders with both major mental disorders (10) and schizophrenia (11).

We proposed that criminals with organic brain syndrome could also be divided into two distinct offending types. We predicted that late starters would begin offending as they developed organic brain syndrome, whereas early starters would have a long history of offending before the onset of organic brain syndrome. This early/late starter typology has important implications for treatment and policy. Specifically, late starters seem to fit a medical model of dysfunction. Their antisocial behavior can be conceptualized as the result of disease or injury, which may involve progressive brain degeneration or readjustment. Depending on the nature of their disease, these patients may respond to medication or behavioral training programs (12). In contrast, early starters display a more generalized pattern of antisocial behavior evident from at least early adolescence. Patients who show this pattern, either alone or comorbid with mental illness, are disruptive, noncompliant, and a challenge to any treatment service (13).

To test our early/late starter hypothesis, we examined the crime and hospital records of 565 male criminals with a diagnosis of organic brain syndrome (primary study group) and 565 male criminals without a diagnosis of organic brain syndrome (comparison group). These men were drawn from a total birth cohort of all individuals born between 1944 and 1947 in Denmark (women were not examined because of an insufficient sample size). Unlike previous studies, our data set allowed us to examine a large number of organic brain syndrome individuals from many different psychiatric hospitals. In addition, our data enabled us to analyze patterns of demographic characteristics, substance use, and personality disorders among organic brain syndrome offenders. We predicted that among male criminals with organic brain syndrome, early starters (those who committed their first crime by age 18) would commit more felony-level and more violent crimes, use more drugs and alcohol, and display more personality disorders than late starters (those whose onset of criminal activity occurred at age 19 or after). We further predicted that early starters would begin committing crimes before the onset of organic brain syndrome, whereas late starters would not begin offending until after the onset of organic brain syndrome. Finally, we hypothesized that before the onset of organic brain syndrome, early starters would have more arrests per year than late starters, whereas after the onset of organic brain syndrome, late starters would have more arrests per year than early starters. In addition, we conducted a series of exploratory analyses to determine whether early and late starters with organic brain syndrome tended to commit their first crime before or after receiving a diagnosis of substance abuse.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from a birth cohort comprising all persons born in Denmark between January 1, 1944, and December 31, 1947 (age 44 was used as a cutoff for all participants). Exactly 358,180 individuals were born during the selected time period; 22,309 (6.2%) were dropped from the original sample because of death or emigration, leaving a total of 335,871 subjects in the cohort.

Our selected study group included all of the men in the cohort with at least one psychiatric hospitalization, a diagnosis of organic brain syndrome, and at least one criminal arrest (N=565). In addition, for a subset of analyses, we examined a randomly selected, same-size comparison group of male criminals in the cohort with no history of hospitalization for organic brain syndrome. Within this total group of 1,130 offenders, 341 (30.2%) of the participants were arrested for the first time by age 18 and were therefore classified as early starters; 789 (69.8%) of the participants were arrested for the first time at or after age 19 and were therefore classified as late starters. Age 18 was selected as the early/late starter cutoff because it denotes adulthood in Denmark and has been used in previous studies of this type (10, 11). The mean age of first arrest for early starters was 16.5 years (SD=1.0, range=15–18), whereas the mean age of first arrest for late starters was 29.5 years (SD=8.1, range=19–44). Within the organic brain syndrome group (N=565), the mean age at onset of organic brain syndrome in early starters was 33.1 years (SD=6.6, range=19–44), and for the late starters it was 34.2 years (SD=6.5, range=18–44).

Participants were divided into marital status categories of single, married, divorced, or widowed for the purposes of data analysis. Within the 1,130-person study group, 282 (25.0%) participants were single, 408 (36.1%) were married, 426 (37.7%) were divorced, and 14 (1.2%) were widowed. Participants were also classified as being of high (6.4%, N=62 of 966), medium (23.3%, N=225), or low (70.3%, N=679) socioeconomic status, which was based on occupational status as classified according to Svalastoga’s 8-point prestige scale (14), a revised version of which was developed for the Danish population. Occupational category was not available for 14.5% (N=164) of the participants. As per the recommendation of Cohen and Cohen (15), missing socioeconomic status data were recoded to the mean, and a dummy coded variable (1=socioeconomic data missing, 0=socioeconomic data present) was included as a statistical control in the logistic regression analyses (results did not change when cases with missing socioeconomic status were dropped from the analyses).

Criminal Register

Official arrest and conviction data through 1991 were obtained from the Danish National Police Register in Copenhagen. As Wolfgang (16) noted, “the criminal registry office in Denmark is probably the most thorough, comprehensive, and accurate in the Western world.” Previous studies have suggested that conviction rates for the mentally ill are likely to underestimate the number of actual offenses committed (17). Therefore, arrest rates rather than conviction rates were analyzed in this study. Danish police are given little discretion in arrests, thus reducing bias that may occur in the criminal justice system’s response to the mentally disordered at the level of arrests.

Clearance rates reflect the percent of reported crimes that result in arrest and conviction. Clearance rates for felony-level crimes in Denmark ranged from 10.2% for the theft of mopeds to 97.7% for homicide at the time these data were collected.

Violent offenses included the following violations of the Danish Penal Code: murder, attempted murder, rape, violence against authority, assault, domestic violence, and robbery. Felony-level offenses included all violent offenses as well as theft, breaking and entering, fraud, forgery, pimping, arson, and narcotics offenses. Recidivism was defined as multiple arrests for felony-level offenses, and violent recidivism was defined as multiple arrests for violent offenses.

The criminal registry also contains information about the amount of time offenders spent in jail. Early starters spent an average of 551 days in jail, whereas late starters spent an average of 160 days in jail (t=4.4, df=1128, p<0.05). This difference in jail time is consistent with our two-type model (i.e., individuals with long-standing patterns of antisocial behavior [early starters] were more likely to be incarcerated for extended periods of time than individuals without these behaviors [late starters]). The variable time spent in jail was included as a statistical control in all of our analyses.

Psychiatric Register

Records of psychiatric hospitalizations through 1991 were obtained from the Danish Psychiatric Register at the Institute for Psychiatric Demography in Aarhus, Denmark. This register contains information on all dates of admission and discharge to psychiatric hospitals in Denmark and the codes for primary, secondary, and tertiary diagnoses according to ICD-8. Previous studies employing data from the Psychiatric Register have found an agreement rate of over 90% between the ICD-8 diagnoses and the diagnostic systems of DSM-III and DSM-III-R.

For the purposes of this study, organic brain syndrome was defined per ICD-8 as a persistent impairment of comprehension caused by dementia, delirium, infection, injury, or substance-induced psychosis. Substance abuse was defined per ICD-8 as a diagnosis of either alcohol or drug dependence or abuse, excluding cases of alcoholic psychosis. Antisocial personality disorder was defined per ICD-8 as a personality disorder characterized by disregard for social obligations, lack of feeling for others, and impetuous violence or callous unconcern. It should be noted that hospitalization rates for antisocial personality disorder significantly underestimate the prevalence of the disorder in the general population.

The Psychiatric Register also contains information about the amount of time individuals spent in the hospital. Early starters spent an average of 180 days in the hospital; late starters were hospitalized an average of 205 days (t=–0.73, df=1128, n.s.).

All data were obtained through archives, and at no time following register linkage was personal information linked to the data. Permission for archives searches was obtained from officials in Denmark.

Statistical Analysis

Logistic regression analyses were used to compare early and late starters on the following variables: history of recidivism for felony-level and violent offenses, history of antisocial personality disorder diagnoses, history of alcohol abuse diagnoses, and history of drug abuse diagnoses. Chi-square analyses were used to determine whether early and late starters tended to commit their first crime before, after, or at the same age they first received a diagnosis of substance abuse.

Analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were used to examine changes in rates of offending per year following the first hospitalization for organic brain syndrome, for both early and late starters, and the age of first offense compared to the age of first substance abuse diagnosis for both early and late starters.

All analyses controlled for marital status, time spent in jail, and socioeconomic status. Alpha levels were set at 0.05. All statistical tests were two-tailed.

Results

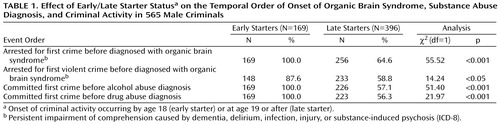

Logistic regression analyses were performed to examine the effect of early/late starter status on the dependent variable of recidivism (coded as yes or no). Despite being the same age and having been incarcerated for longer periods of time, early starters were significantly more recidivistic than late starters (χ2=40.62, df=1, p<0.001). In addition, there was a significant interaction between early/late starter status and organic brain syndrome, such that early starters with organic brain syndrome were more recidivistic than early starters without organic brain syndrome and late starters with or without organic brain syndrome (χ2=6.40, df=1, p<0.05) (Figure 1).

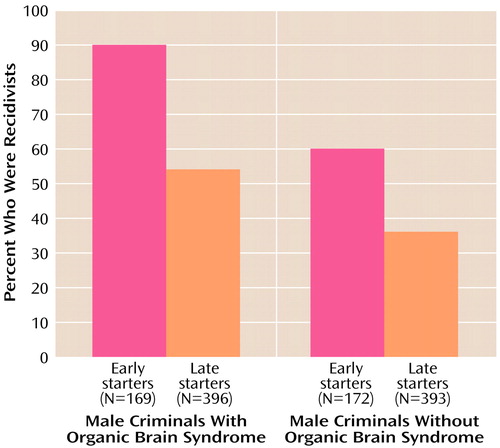

Logistic regression analyses were also performed to examine the effect of early/late starter status on the dependent variable of violent recidivism (coded as yes or no). While early starters were significantly more likely than late starters to be violent recidivists (χ2=21.50, df=1, p<0.001), the interaction between early/late starter status and organic brain syndrome was not significant (χ2=1.35, df=1, p>0.05) (Figure 2).

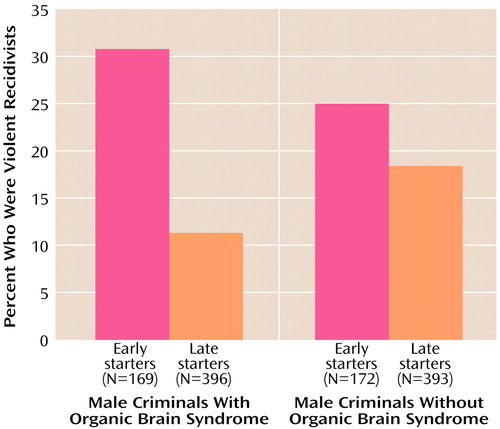

Among the 565 male criminals with organic brain syndrome, logistic regression analyses examining the effects of early/late starter status on the dependent variable of secondary diagnoses revealed that early starters were 1) significantly more likely than late starters to have a secondary diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder (χ2=6.44, df=1, p<0.05), 2) more likely than late starters to have a secondary diagnosis of drug abuse (χ2=3.15, df=1, p<0.08), and 3) equally as likely as late starters to have a secondary diagnosis of alcohol abuse (χ2=0.35, df=1, n.s.) (Figure 3).

ANCOVAs were conducted to examine the effect of early/late starter status on the dependent variable of mean number of arrests per year both before and after the onset of organic brain syndrome. Results indicated that, before the onset of organic brain syndrome, early starters had significantly more arrests per year (mean=0.39, SD=0.37) than late starters (mean=0.10, SD=0.18) (F=136.48, df=1, 564, p<0.001). In contrast, after the onset of organic brain syndrome, there were no differences in the arrest rates of early (mean=0.27, SD=0.52) and late (mean=0.24, SD=0.51) starters (F=0.13, df=1, 564, n.s.).

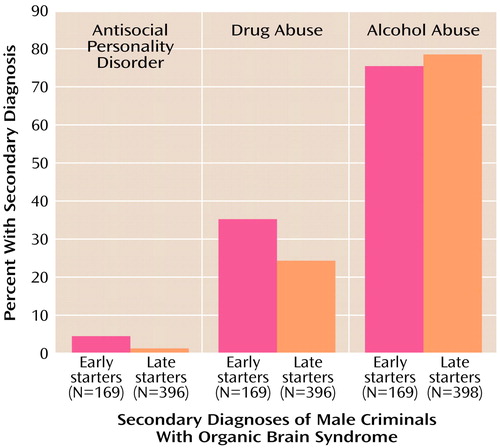

Logistic regression analyses were performed to examine the effect of early/late starter status on the dependent variable of the temporal order of onset of organic brain syndrome, substance abuse diagnosis, and criminal activity (Table 1). Analyses revealed that early starters were more likely than late starters to have their first arrest for a felony-level crime before the onset of organic brain syndrome. Early starters were also more likely than late starters to have their first violent arrest before the onset of organic brain syndrome. Finally, early starters were more likely than late starters to commit their first crime before being diagnosed with both alcohol abuse and drug abuse (Table 1).

Follow-up analyses examining the effects of early/late starter status on the dependent variable of age of first arrest versus age of first substance abuse diagnosis revealed that early starters committed their first crime an average of 15.1 years before receiving a diagnosis of alcohol abuse, whereas late starters committed their first crime an average of 2.8 years before receiving a diagnosis of alcohol abuse (F=174.24, df=1, 564, p<0.001). Similarly, early starters committed their first crime an average of 13.2 years before receiving a diagnosis of drug abuse, whereas late starters committed their first crime an average of 1.5 years after receiving a diagnosis of drug abuse (F=64.51, df=1, 564, p<0.001).

Discussion

The results of this study support our hypothesis that organic brain syndrome offenders can be divided into two distinct types on the basis of age at first arrest. These types exhibit different patterns of criminal behavior and provide different challenges to treatment providers. In comparison to late starters, early starters 1) were more likely to be arrested before the onset of organic brain syndrome; 2) accumulated more arrests per year before, but not after, the onset of organic brain syndrome; 3) were more likely to be criminal recidivists and violent recidivists; 4) were more likely to have a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder; and 5) were somewhat more likely to have a diagnosis of drug abuse. In addition, there was a significant interaction between early/late starter status and recidivism. Specifically, early starters with organic brain syndrome committed significantly more crimes than early starters without organic brain syndrome. This finding could be interpreted to suggest that early starters who engage in reckless behavior are more likely to develop organic brain syndrome than early starters who do not engage in reckless behavior.

While research has demonstrated that a previous history of offending, particularly violent offending, is one of the best predictors of criminal behavior (18), this was not the case among men with organic brain syndrome. Rather, once organic brain syndrome was present, rates of offending among early and late starters were similar. This result, if replicated, could be integrated into clinical instruments used to assess the risk of violence.

We are somewhat hesitant to interpret our findings on antisocial personality disorder. At the time subjects in this study were hospitalized, it was uncommon for organic brain syndrome patients to be diagnosed with a personality disorder. In addition, clinicians may have viewed these diagnoses as unreliable given the instability and ongoing change in personality traits that follow the onset of brain damage. Thus, it is possible that clinicians did not bother to make personality disorder diagnoses for some of their organic brain syndrome patients. In contrast, clinicians may have judged that alcohol and drug use were quite relevant to the onset of organic brain syndrome and to decisions about the patient’s long-term care. Consistent with previous research (19, 20), the present study revealed that early starters were more likely than late starters to commit their first crime before being diagnosed with a substance abuse disorder. It is surprising, however, that among those with organic brain syndrome, early starters did not present higher rates of substance use disorders than late starters, given recent evidence that early starters are exposed to alcohol and drugs earlier than their peers (19).

As hypothesized, early starters were more likely than late starters to be arrested before receiving a diagnosis of organic brain syndrome. Despite this difference, it is important to note that the majority of late starters were actually arrested before first being diagnosed with organic brain syndrome. These findings do not necessarily contradict our theoretical model. For example, it is possible that organic brain syndrome was influencing the criminal behavior of late starters long before they were formally diagnosed and admitted to a psychiatric ward. Because our diagnostic and criminal data were obtained from archival records, we cannot pinpoint the exact onset of criminal behavior or organic brain syndrome. Future longitudinal studies interviewing large-scale community samples will be necessary to more accurately examine the temporal order of organic brain syndrome and crime in both early and late starter groups.

The results of this study are consistent with the findings of Hodgins et al. (10), which suggested that early and late starters display different patterns of criminal offending, substance use, and personality disorders. In addition, this study suggests that there is a specific interaction between early/late starter status and organic brain syndrome, such that early starters with organic brain syndrome are at particular risk for criminal offending. Future studies are needed to delineate the importance of the early/late start offending typology for the treatment of patients with organic brain syndrome. For example, although we found that rates of offending among early and late starters were similar after the onset of organic brain syndrome, we hypothesize that treatment compliance would be worse among early starters.

Our results have important implications for the assessment of criminality and violence among patients with organic brain syndrome. Previous studies have found that this population is responsible for a considerable number of the violent incidents on inpatient psychiatric wards. Yet, findings from the present investigation suggest that the most commonly used standardized risk assessment instruments, such as the HCR-20 (21), would underestimate the risk of violence among late starters, since so much emphasis is placed on historical variables. Finally, the results of the present study could be used to inform future investigations of etiological factors underlying criminal behavior.

The results of this study may play an important role in risk assessment. Compared to early offenders without organic brain syndrome, early starters with organic brain syndrome may be at particular risk for antisocial behavior and recidivism. In addition, organic brain syndrome patients with no criminal history may rapidly become at risk for offending because of their brain disorder. These findings underlie the importance of investigating the association of brain structure and activity in the development of offending and violent behavior.

|

Received April 20, 2000; revision received Dec. 8, 2000; accepted Jan. 4, 2001. From the Department of Psychology, Emory University; and the Institute of Preventive Medicine, Copenhagen. Address reprint requests to Ms. Grekin, Department of Psychology, Emory University, Atlanta, GA 30322; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by NIMH grant MH-50017, National Institute of Justice grant CX0063, grants from Fonds concerte d’aide a la recherche and the Social Science and Humanities Research Council, and an NIH Research Scientist Award (Dr. Mednick). The authors thank Fini Schulsinger, Poul Munk-Jorgensen, Freddy Pederson, Marianne Engberg, and Margit Bybjerg for their assistance in the data collection phase of this study.

Figure 1. Effect of Early/Late Starter Statusa on Recidivism in 1,130 Male Criminals With or Without Organic Brain Syndromeb

aOnset of criminal activity occurring by age 18 (early starter) or at age 19 or after (late starter).

bPersistent impairment of comprehension caused by dementia, delirium, infection, injury, or substance-induced psychosis (ICD-8).

Figure 1. Effect of Early/Late Starter Statusa on Violent Recidivism in 1,130 Male Criminals With or Without Organic Brain Syndromeb

aOnset of criminal activity occurring by age 18 (early starter) or at age 19 or after (late starter).

bPersistent impairment of comprehension caused by dementia, delirium, infection, injury, or substance-induced psychosis (ICD-8).

Figure 3. Effect of Early/Late Starter Statusa on Secondary Diagnoses in 565 Male Criminals With Organic Brain Syndromeb

aOnset of criminal activity occurring by age 18 (early starter) or at age 19 or after (late starter).

bOrganic brain syndrome was defined as persistent impairment of comprehension caused by dementia, delirium, infection, injury, or substance-induced psychosis (ICD-8). Substance abuse was defined as a diagnosis of alcohol or drug dependence or abuse according to the ICD-8 criteria.

1. Hodgins S: Mental disorder, intellectual deficiency, and crime: evidence from a birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:476-483Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hodgins S, Mednick SA, Brennan PA, Schulsinger F, Engberg M: Mental disorder and crime: evidence from a Danish birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996; 53:489-496Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Tiihonen J, Isohanni M, Rasanen P, Koiranen M, Moring J: Specific major mental disorders and criminality: a 26-year prospective study of the 1966 Northern Finland Birth Cohort. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:840-845Link, Google Scholar

4. Tardiff K, Sweillam A: Assault, suicide and mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980; 37:164-169Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Travin S, Lee HK, Bluestone H: Prevalence and characteristics of violent patients in a general hospital. NY State J Med 1990; 90:591-595Medline, Google Scholar

6. Martell DA: Estimating the prevalence of organic brain dysfunction in maximum-security forensic psychiatric patients. J Forensic Sci 1992; 37:878-893Medline, Google Scholar

7. Convit A, Isay D, Otis D, Volavka J: Characteristics of repeatedly assaultive psychiatric inpatients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990; 41:1112-1115Google Scholar

8. Brennan PA, Mednick SA, Hodgins S: Major mental disorders and criminal violence in a Danish birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000; 57:494-500Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Leygraf N: Psychisch kranke Straftater: Epidemiologie und aktuelle Praxis des psychitrischen Massregelvollzugs. Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 1988Google Scholar

10. Hodgins S, Cote G, Toupin J: Major mental disorder and crime: an etiological hypothesis, in Psychopathy: Theory, Research and Implications for Society. Edited by Cooke DJ. Dordrecht, the Netherlands, Kluwer, 1998, pp 231-256Google Scholar

11. Tengstrom A, Hodgins S, Kullgren G: Men with schizophrenia who behave violently: the usefulness of an early versus late-start offender typology. Schizophr Bull 2001; 27:205-218Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Nedopil N: Offenders with brain damage, in Violence, Crime and Mentally Disordered Offenders: Concepts and Methods for Effective Treatment and Prevention. Edited by Hodgins S, Muller-Isberner R. London, John Wiley & Sons, 2000, pp 39-62Google Scholar

13. Hodgins S, Muller-Isberner R: Violence, Crime and Mentally Disordered Offenders: Concepts and Methods for Effective Treatment and Prevention. Edited by Hodgins S, Muller Isberner R. London, John Wiley & Sons, 2000Google Scholar

14. Svalastoga K: Prestige, Class and Mobility. Copenhagen, Ayer, 1959Google Scholar

15. Cohen J, Cohen P: Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1975Google Scholar

16. Wolfgang ME: Foreword, in Biosocial Bases of Criminal Behavior. Edited by Mednick SA, Christiansen KO. New York, Gardener Press 1977, pp v-viGoogle Scholar

17. Paull D, Malek RA: Psychiatric disorders and criminality (letter). JAMA 1974; 228:1369Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Binder RL: Are the mentally ill dangerous? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 1999; 27:189-201Medline, Google Scholar

19. Kratzer L, Hodgins S: A typology of offenders: a test of Moffit’s theory among males and females from childhood to age 30. Criminal Behaviour and Ment Health 1999; 9:57-73Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Hodgins S: Status at age 30 of children with conduct problems. Crime and Crime Prevention 1994; 3:41-62Google Scholar

21. Douglas KS, Ogloff JR, Nicholls TS, Grant I: Assessing risk for violence among psychiatric patients: the HCR-20 violence risk assessment scheme and the Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version. J Consult Clin Psychol 1999; 67:917-930Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar