Hypnotizability in Acute Stress Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study investigated the relationship between acute dissociative reactions to trauma and hypnotizability. METHOD: Acutely traumatized patients (N=61) with acute stress disorder, subclinical acute stress disorder (no dissociative symptoms), and no acute stress disorder were administered the Stanford Hypnotic Clinical Scale within 4 weeks of their trauma. RESULTS: Although patients with acute stress disorder and patients with subclinical acute stress disorder displayed comparable levels of nondissociative psychopathology, acute stress disorder patients had higher levels of hypnotizability and were more likely to display reversible posthypnotic amnesia than both patients with subclinical acute stress disorder and patients with no acute stress disorder. CONCLUSIONS: The findings may be interpreted in light of a diathesis-stress process mediating trauma-related dissociation. People who develop acute stress disorder in response to traumatic experience may have a stronger ability to experience dissociative phenomena than people who develop subclinical acute stress disorder or no acute stress disorder.

The introduction of acute stress disorder in DSM-IV has resulted in renewed interest in the role of dissociation in acute stress reactions. Acute stress disorder comprises dissociative, reexperiencing, avoidance, and arousal symptoms (1). The rationale for the acute stress disorder diagnosis was that dissociative symptoms in the acute phase would impede access to and resolution of traumatic memories and their associated affect and consequently contribute to ongoing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (2). Prospective studies have indicated that approximately 80% of people who meet criteria for acute stress disorder subsequently develop chronic PTSD (3–7). These studies have also reported that most people who meet all the acute stress disorder criteria except for dissociation also develop PTSD (5, 6). On the basis of these findings, it has been proposed that there are multiple pathways to development of PTSD; whereas some acutely traumatized people who later develop PTSD display acute dissociation, others can develop PTSD without acute dissociation (8). These findings raise the question of why some people respond to trauma with dissociation and others do not.

It has long been argued that dissociation occurs in the face of overwhelming stress in people who are constitutionally predisposed to dissociative mechanisms (9). More recently, it has been proposed that dissociative tendencies may not predispose people to developing a mental disorder but may shape the nature of a disorder should one develop after a trauma (10, 11). More specifically, it has been proposed that individuals who are prone to dissociation are particularly likely to display dissociative symptoms in the acute trauma phase (11). Accordingly, this diathesis-stress proposal would suggest that individuals who have a dissociative predisposition would develop acute stress disorder, whereas those without this tendency would display acute stress symptoms without dissociative symptoms.

We tested this proposal by measuring levels of hypnotizability in individuals with acute stress disorder, subclinical acute stress disorder (i.e., no dissociative reactions), and no acute stress disorder. Some investigators have argued that dissociative disorders are a pathological form of a dissociative tendency that is seen in normal populations and that can be reflected in hypnotizability (12, 13). In contrast to this view, there is increasing recognition that hypnotizability is a multifaceted construct that comprises a range of related processes, including absorption, suggestibility, dissociation, and fantasy proneness (14, 15). Although hypnotizability cannot be equated with dissociation, it may reflect cognitive processes that are associated, albeit indirectly, with dissociative mechanisms observed in psychopathological dissociation (10). This proposal is consistent with findings that higher levels of hypnotizability have been observed in a range of psychiatric disorders that purportedly involve a dissociative process, including PTSD (16, 17), dissociative identity disorder (18, 19), phobias (20), and bulimia nervosa (21). On the premise that hypnotizability is a construct that is related to processes manifested in dissociative disorders, we expected that subjects with acute stress disorder would show higher levels of hypnotizability than either those with subclinical acute stress disorder or those with no acute stress disorder.

Posthypnotic amnesia has traditionally been regarded as a core dissociative phenomenon because subjects who are given a hypnotic suggestion for amnesia cannot recall events that occurred during hypnosis (22). Although posthypnotic amnesia is routinely studied by measuring subjects’ inability to recall certain events before the cancellation of the amnesia suggestion, it has been argued that dissociative amnesia is more accurately measured by comparing the number of events hypnotized subjects forget with the number of events they recall after the amnesia suggestion has been canceled (23). The need to strictly operationalize posthypnotic amnesia in this way is reflected in findings that between 78% and 100% of patients with schizophrenia who are hypnotized are unable to recall most events after an amnesia suggestion, but relatively few display reversibility of this amnesia after cancellation of the suggestion (24, 25). To further assess the relationship between acute stress disorder and the capacity for dissociative responses, we predicted that subjects with acute stress disorder would be more likely to display reversible posthypnotic amnesia than those with subclinical acute stress disorder and no acute stress disorder.

Method

Subjects

Sixty-one consecutive referrals to a major trauma hospital or to the PTSD Unit at Westmead Hospital in Sydney, Australia, were assessed within 1 month posttrauma. Exclusion criteria included 1) inability to comprehend all interview questions without the aid of an interpreter (N=5), 2) evidence of traumatic brain injury (N=6), 3) prescription of narcotic analgesia (with the exception of codeine) for the first 4 weeks posttrauma (N=2), and 4) age less than 16 or more than 65 years (N=4). The final sample included 32 male patients and 29 female patients who ranged in age from 16 to 60 years (mean=32.02 years, SD=10.47). Thirty patients were motor vehicle accident survivors, and 31 were nonsexual assault victims.

Procedure

After a description of the study, the patients’ written informed consent was obtained. The first assessment involved the administration of the Acute Stress Disorder Interview (26), a structured clinical interview that contains 19 dichotomously scored items grouped according to the four clusters of acute stress disorder symptoms (dissociation, reexperiencing, avoidance, and arousal). The instrument provides a total score of acute stress severity (range=1–19). The Acute Stress Disorder Interview possesses sound test-retest reliability at an interval between 1 and 3 weeks (r=0.95) and high levels of sensitivity (91%) and specificity (93%) relative to independent clinician diagnoses (26). Patients were also administered the Impact of Event Scale (27), the Beck Depression Inventory (28), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (29), and the Dissociative Experiences Scale-Taxon (30), which consists of a subset of questions from the original Dissociative Experiences Scale (31). Between 1 and 3 days later, patients were administered the Stanford Hypnotic Clinical Scale (32) by an independent clinical psychologist who was blind to the diagnostic status of the patient. The Stanford Hypnotic Clinical Scale is a standardized assessment of hypnotic susceptibility that involves a hypnotic induction, followed by five hypnotic suggestions (hand lowering, age regression, dream, posthypnotic suggestion, and posthypnotic amnesia). Each item is scored by the hypnotist as passed or failed on the basis of the observed and reported response of the subject. Scale scores are normally distributed and correlate strongly with established measures of hypnotizability (e.g., r=0.72 for the correlation with scores on the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale: Form C [33]). Patients were informed that the Stanford Hypnotic Clinical Scale was being administered to assist “our understanding of how trauma influences how people think and feel.”

Results

Subject Characteristics

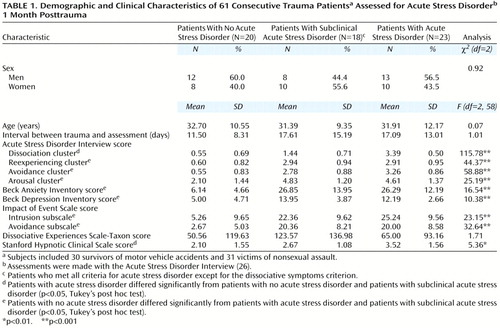

On the basis of patients’ responses to the Acute Stress Disorder Interview, 23 patients had acute stress disorder, 18 had subclinical acute stress disorder, and 20 had no acute stress disorder. Table 1 presents demographic and clinical characteristics of the three groups. The gender composition of the three groups was similar. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) of data for the three groups showed no differences in age or length of time between the trauma and the assessment. As expected, the patients with acute stress disorder and with subclinical acute stress disorder scored higher than the patients with no acute stress disorder on each of the psychopathology measures. The patients with acute stress disorder differed from those with subclinical acute stress disorder only in scores on the dissociation cluster of the Acute Stress Disorder Interview, on which acute stress disorder patients scored higher than the subclinical acute stress disorder patients.

Hypnotizability

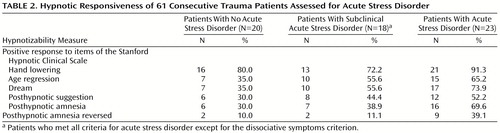

Results of a one-way ANOVA showed that the patients with acute stress disorder had a higher level of hypnotizability, as indicated by higher scores on the Stanford Hypnotic Clinical Scale, than the patients with subclinical acute stress disorder and those with no acute stress disorder (Table 1). To further assess the role of acute dissociative symptoms in hypnotizability, patients’ scores on the Stanford Hypnotic Clinical Scale were examined with an analysis of covariance that controlled for the effect of scores on the dissociative cluster of the Acute Stress Disorder Interview. This analysis indicated no significant differences between groups (F=2.23, df=2, 38, n.s.). Table 2 presents the proportions of patients in each group who showed hypnotic responsiveness to each item on the Stanford Hypnotic Clinical Scale. The proportion of patients with hypnotic responsiveness in three groups differed significantly for the dream item (χ2=6.56, N=61, df=2, p<0.05) and the posthypnotic amnesia item (χ2=7.48, N=61, df=2, p<0.05). Paired chi-square comparisons indicated that patients with acute stress disorder were more likely to respond to the dream item than patients with no acute stress disorder (χ2=6.69, N=43, df=1, p<0.01, with Yates’s correction [34]) and more likely to respond to the posthypnotic amnesia item than both patients with no acute stress disorder (χ2=6.80, N=43, df=1, p<0.01, with Yates’s correction) and patients with subclinical acute stress disorder (χ2=3.86, N=41, df=1, p<0.05, with Yates’s correction).

We operationalized reversible amnesia by defining it as reporting an additional two items of the possible five items on the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale: Form C after the amnesia suggestion was canceled. Patients with acute stress disorder patients were significantly more likely to display reversible amnesia than both patients with subclinical acute stress disorder (χ2=4.32, N=41, df=1, p<0.05, with Yates’s correction) and patients with no acute stress disorder (χ2=4.72, N=43, df=1, p<0.05, with Yates’s correction) (Table 2).

Correlational Analysis

To assess the relationship between hypnotizability and psychopathology, scores on the Stanford Hypnotic Clinical Scale were correlated with each of the psychopathology scores by using Pearson product-moment correlation. Significant correlations were found between the Stanford Hypnotic Clinical Scale scores and the Acute Stress Disorder Interview cluster scores for dissociation (r=0.37, df=59, p<0.01) and reexperiencing (r=0.26, df=59, p<0.05). Nonsignificant correlations were found between the Stanford Hypnotic Clinical Scale scores and the Acute Stress Disorder Interview cluster scores for avoidance (r=0.22, df=59, p=0.09) and arousal (r=0.17, df=59, p=0.18), Beck Anxiety Inventory scores (r=0.16, df=59, p=0.54), Beck Depression Inventory scores (r=0.09, df=59, p=0.27), Impact of Event Scale intrusion subscale scores (r=0.18, df=59, p=0.18), Impact of Event Scale avoidance subscale scores (r=0.14, df=59, p=0.31), and Dissociative Experiences Scale-Taxon scores (r=0.05, df=59, p=0.71).

Discussion

Patients who met the full criteria for acute stress disorder displayed higher levels of hypnotizability than patients with either subclinical or no acute stress disorder. This finding replicates those of previous studies in which higher hypnotizability levels have been observed in populations that display some dissociative manifestation (16–19). Further, more patients with acute stress disorder displayed reversible amnesia, compared with patients with subclinical or no acute stress disorder. These findings add additional support for the idea that people who develop acute stress disorder after trauma may have a stronger ability to experience dissociative phenomena than those who do not develop this disorder. It is important to note that the clinical presentation of the patients with acute stress disorder and those with subclinical acute stress disorder differed only in terms of their dissociative symptoms. Moreover, when dissociative symptoms were controlled for, patients with acute stress disorder and those with subclinical acute stress disorder did not differ in level of hypnotizability. Accordingly, the different levels of hypnotizability in these two groups cannot be attributed simply to differences in severity of posttraumatic stress.

This finding may be explained in terms of a diathesis-stress process for acute stress disorder, in which people who have a predisposition toward dissociation may respond to a traumatic experience with the dissociative symptoms that are included as criteria for the acute stress disorder diagnosis. In contrast, those who have a lesser tendency for dissociative processes may respond to a trauma with acute stress reactions that employ mechanisms that are not dissociative in nature (and which we have termed subclinical acute stress disorder). This explanation is consistent with the proposal that whereas dissociative tendencies may not predispose people to mental disorders, they may shape the form of mental disturbance should a disorder develop (10, 11). We recognize that any test of a diathesis-stress model requires prospective investigation of hypnotizability before and after the trauma. However, there is evidence that hypnotizability remains stable across time, with test-retest correlations of at least 0.60 over periods of 10 to 25 years (35).

It is important to acknowledge that hypnotizability is a multidimensional construct involving processes that are distinct from dissociation (14). There are several possible mechanisms that may mediate the relationship between hypnotizability scores and dissociative symptoms. For example, acutely traumatized individuals with a greater tendency toward absorption in subjective experiences (which is strongly correlated with hypnotizability [36]) may become more focused on internal rather than external events after the trauma. This interpretation is consistent with evidence that dissociation is correlated with absorption and fantasy proneness, which in turn are correlated with hypnotizability (10, 11). This capacity for absorption may result in dissociative experiences after trauma.

We recognize other interpretations. There is strong evidence that hypnotic responsiveness is influenced by contextual factors (37). It is possible that a proportion of patients in this study perceived the questions about dissociative aspects of acute stress disorder in a way that cued them to respond positively to the hypnotic testing. This possibility needs to be recognized, because acute stress disorder was assessed by using directive questions embedded in a structured clinical interview (the Acute Stress Disorder Interview). This interpretation is consistent with claims that highly hypnotizable individuals, who are particularly suggestible, may be more prone to therapeutic suggestions that they experience dissociative symptoms (38).

An unexpected finding was that acute stress disorder was not associated with scores on the Dissociative Experiences Scale-Taxon, which is derived from the original Dissociative Experiences Scale and purportedly measures psychopathological dissociation (30). This finding is consistent with previous reports that scores on the Dissociative Experiences Scale are more reflective of general psychopathology than of dissociation (39). Similarly, we found that scores on the Dissociative Experiences Scale-Taxon correlated only with scores on the Beck Depression Inventory. The finding that Dissociative Experiences Scale-Taxon scores correlated poorly with level of hypnotizability (r=0.05) is consistent with a report of a low correlations between the Dissociative Experiences Scale and a measure of hypnotizability when the two instruments were administered in different contexts (40).

The current findings have theoretical and clinical implications. Theoretically, these data suggest that a diathesis-stress model for dissociative symptoms in acute trauma reactions deserves more rigorous investigation. These data suggest one predisposing variable that may explain why only some people who subsequently develop PTSD display acute dissociation after trauma. We emphasize that this inference requires prospective study to clarify the relationships between hypnotizability, absorption, and fantasy proneness and the vulnerability to acute dissociation and long-term PTSD. From a clinical perspective, these results suggest that people with acute stress disorder may be particularly adept at responding to hypnosis and that this technique may have particular therapeutic benefits for people with acute stress disorder.

|

|

Received Feb. 17, 2000; revision received Aug. 8, 2000; accepted Oct. 12, 2000. From the School of Psychology, University of New South Wales. Address reprint requests to Dr. Bryant, School of Psychology, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052 Australia; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council.

1. Bryant RA, Harvey AG: Acute stress disorder: a critical review of diagnostic issues. Clin Psychol Rev 1997; 17:757–773Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Spiegel D, Koopman C, Cardeña E, Classen C: Dissociative symptoms in the diagnosis of acute stress disorder, in Handbook of Dissociation: Theoretical, Empirical, and Clinical Perspectives. Edited by Michelson LK, Ray WJ. New York, Plenum, 1996, pp 367–380Google Scholar

3. Brewin CR, Andrews B, Rose S, Kirk M: Acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in victims of violent crime. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156:360–366Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Bryant RA, Harvey AG: Relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder following mild traumatic brain injury. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:625–629Link, Google Scholar

5. Harvey AG, Bryant RA: The relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder following motor vehicle accidents. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998; 66:507–512Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Harvey AG, Bryant RA: Relationship of acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: a two-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol 1999; 67:985–988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Harvey AG, Bryant RA: Two-year prospective evaluation of the relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder following mild traumatic brain injury. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157:626–628Link, Google Scholar

8. Bryant RA, Harvey AG: Acute Stress Disorder: A Handbook of Theory, Assessment, and Treatment. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2000Google Scholar

9. Janet P: The Major Symptoms of Hysteria. New York, McMillan, 1907Google Scholar

10. Kihlstrom JF, Glisky ML, Angiulo MJ: Dissociative tendencies and dissociative disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 1994; 103:117–124Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Butler LD, Duran RE, Jasiukaitis P, Koopman C, Spiegel D: Hypnotizability and traumatic experience: a diathesis-stress model of dissociative symptomatology. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:42–63Link, Google Scholar

12. Bernstein EM, Putnam FW: Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986; 174:727–735Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bliss EL: Hypnosis and hysteria. J Nerv Ment Dis 1984; 172:203–206Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Frankel FH: Hypnotizability and dissociation. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:823–839Link, Google Scholar

15. Woody EZ, Bowers KS, Oakman JM: A conceptual analysis of hypnotic responsiveness: experience, individual differences, and context, in Contemporary Hypnosis Research. Edited by Fromm E, Nash MR. New York, Guilford, 1992, pp 3–33Google Scholar

16. Spiegel D, Hunt T, Dondershine HE: Dissociation and hypnotizability in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145:301–305Link, Google Scholar

17. Stutman RK, Bliss EL: Posttraumatic stress disorder, hypnotizability, and imagery. Am J Psychiatry 1985; 142:741–743Link, Google Scholar

18. Carlson EB, Putnam FW: Integrating research on dissociation and hypnotizability: are there two pathways to hypnotizability? Dissociation 1989; 2:32–38Google Scholar

19. Spiegel D: Multiple personality as a post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1984; 7:101–110Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Frankel FH, Orne MT: Hypnotizability and phobic behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:1259–1261Google Scholar

21. Covino NA, Jimerson DC, Wolfe BE, Franko DL, Frankel FH: Hypnotizability, dissociation, and bulimia nervosa. J Abnorm Psychol 1994; 103:455–459Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Kihlstrom JF: Hypnosis. Ann Rev Psychol 1985; 36:385–418Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Kihlstrom JF, Register PA: Optimal scoring of amnesia on the Harvard Group Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility, Form A. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 1984; 32:51–57Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Lavoie G, Sabourin M, Langlois J: Hypnotic susceptibility, amnesia, and IQ in chronic schizophrenia. Int J Clin Exp Hyp 1973; 21:157–168Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Leiberman J, Lavoie G, Brisson A: Suggested amnesia and order of recall as a function of hypnotic susceptibility and learning condition in chronic schizophrenia patients. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 1978; 26:268–280Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Bryant RA, Harvey AG, Dang ST, Sackville T: Assessing acute stress disorder: psychometric properties of structured clinical interview. Psychol Assess 1998; 10:215–220Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Horowitz MJ, Wilner N, Alvarez W: Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 1979; 41:209–218Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK: Beck Depression Inventory Manual, 2nd ed. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1996Google Scholar

29. Beck AT, Steer RA: Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1990Google Scholar

30. Waller NG, Putnam FW, Carlson EB: Types of dissociation and dissociative types: a taxometric analysis of dissociative experiences. Psychol Methods 1996; 1:300–321Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Bernstein EM, Putnam EW: Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986; 174:727-735Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Morgan AH, Hilgard JR: The Stanford Hypnotic Clinical Scale for adults. Am J Clin Hypn 1978–1979; 21:134–147Google Scholar

33. Weitzenhoffer AM, Hilgard ER: Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale: Form C. Palo Alto, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1963Google Scholar

34. Fleiss JL: Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, 2nd ed. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1981Google Scholar

35. Piccione C, Hilgard ER, Zimbardo PG: On the degree of stability of measured hypnotizability over a 25-year period. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989; 56:289–295Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Roche S, McConkey KM: Absorption: nature, assessment, and correlates. J Pers Soc Psychol 1990; 59:91–101Crossref, Google Scholar

37. Council JR, Kirsch I, Hafner LP: Expectancy versus absorption in the prediction of hypnotic responding. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986; 50:182–189Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Bowers KS: Dissociation in hypnosis and multiple personality disorder. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 1991; 39:155–170Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Nash MR, Hulsey TL, Sexton MC, Harralson TI, Lambert W: Long-term sequelae of childhood sexual abuse: perceived family environment, psychopathology, and dissociation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1993; 61:276–283Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Silva CE, Kirsch I: Interpretative sets, expectancy, fantasy proneness, and dissociation as predictors of hypnotic response. J Pers Soc Psychol 1992; 63:847–856Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar