Development and Validation of a Screening Instrument for Bipolar Spectrum Disorder: The Mood Disorder Questionnaire

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Bipolar spectrum disorders, which include bipolar I, bipolar II, and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified, frequently go unrecognized, undiagnosed, and untreated. This report describes the validation of a new brief self-report screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorders called the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. METHOD: A total of 198 patients attending five outpatient clinics that primarily treat patients with mood disorders completed the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. A research professional, blind to the Mood Disorder Questionnaire results, conducted a telephone research diagnostic interview by means of the bipolar module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. RESULTS: A Mood Disorder Questionnaire screening score of 7 or more items yielded good sensitivity (0.73) and very good specificity (0.90). CONCLUSIONS: The Mood Disorder Questionnaire is a useful screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder in a psychiatric outpatient population.

The lifetime prevalence of bipolar I disorder is approximately 1% (1, 2). However, the prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder is substantially higher. Bipolar spectrum disorder has been described and defined in several ways (3, 4), but it usually includes bipolar I, bipolar II, cyclothymia, and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified. The lifetime prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder has been found to be between 2.6% and 6.5% (5), which is similar to that of drug abuse (4.4%) and many anxiety disorders (1).

Unfortunately, bipolar spectrum disorders often go unrecognized and undiagnosed (6), largely because of the wide range of symptoms seen in patients with bipolar spectrum disorder, including impulsive behavior, alcohol and substance abuse, fluctuations in energy level, and legal problems. These symptoms are often attributed to problems other than bipolar disorder. The consequences of delayed diagnoses or misdiagnoses can be devastating.

One method of increasing recognition of an illness is to screen for it. Although several screening instruments exist for a variety of psychiatric disorders, none exist to screen for bipolar spectrum disorder. This article describes the development and validation of a brief and easy-to-use screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder called the Mood Disorder Questionnaire.

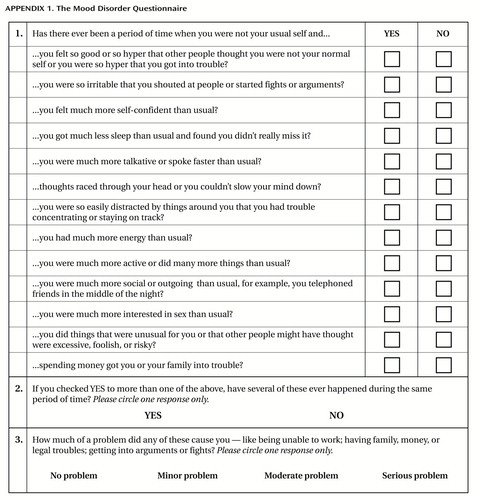

The Mood Disorder Questionnaire is a self-report, single-page, paper-and-pencil inventory that can be quickly and easily scored by a physician, nurse, or any trained medical staff assistant. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire screens for a lifetime history of a manic or hypomanic syndrome by including 13 yes/no items derived from both the DSM-IV criteria and clinical experience (Appendix 1). A yes/no question also asks whether several of any reported manic or hypomanic symptoms or behaviors were experienced during the same period of time. Finally, the level of functional impairment due to these symptoms (“no problem” to “serious problem”) is queried on a 4-point scale. The original version of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire was administered to a convenience group of bipolar patients to assess feasibility and face validity. The items were then revised on the basis of this experience. The present study was designed to determine the optimal symptom threshold for identifying bipolar spectrum disorder and to assess the sensitivity and specificity of this threshold by using a professional mental health diagnosis of bipolar spectrum disorder as the criterion standard.

Method

The study was conducted at five outpatient psychiatric clinics that primarily treat patients with mood disorders, especially bipolar disorder. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each site. Signed informed consent was obtained from each subject. All subjects were English-speaking and at least 18 years old.

Outpatients being seen for treatment were asked to complete the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Patients were contacted to receive a telephone research diagnostic interview within 2 weeks. An experienced psychiatric research social worker, who was blind to the Mood Disorder Questionnaire results, used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (7) to obtain a diagnosis of bipolar spectrum disorder (including bipolar I, bipolar II, and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified).

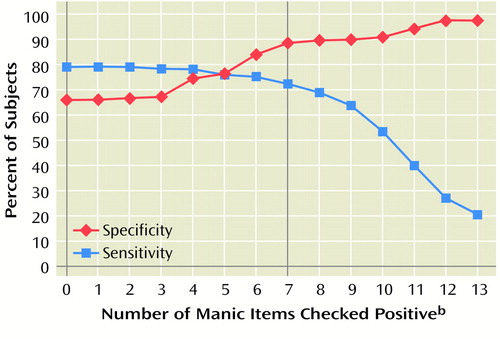

Data for the telephone-diagnosed subjects were analyzed with SPSS 8.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago). A scoring algorithm calculated the number of symptom items scored “yes” (range=0–13). In order to screen positively for bipolar spectrum disorder, in addition to a threshold number of symptom items, the respondent had to check “yes” for the item asking if the symptoms clustered in the same time period and had to indicate that the symptoms caused either “moderate” or “serious” problems. Sensitivity and specificity for each possible Mood Disorder Questionnaire score were plotted by using results from the SCID telephone interview as the standard. Sensitivity (percent of criterion standard diagnoses correctly diagnosed by the Mood Disorder Questionnaire) and specificity (percent of criterion standard noncases correctly identified as noncases by the Mood Disorder Questionnaire) for various symptom threshold cutoff scores were calculated in order to determine the optimal screen threshold.

Results

A group of 198 subjects received the telephone SCID interview. A total of 63% of the subjects were female. The mean age was 44 years (SD=13, range=18–80). A total of 86% had an education of high school level or higher. A total of 90% of the subjects were Caucasian, and 9% were African American.

A SCID diagnosis of bipolar spectrum disorder (bipolar I: N=70, bipolar II: N=26, and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified: N=13) was given to 109 (55%) of the 198 patients. The frequency of endorsement of Mood Disorder Questionnaire items ranged from 34.2% to 77.2% (the highest item endorsements were “easily distracted,” “racing thoughts,” and “irritability”). A Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.90 was achieved for the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Individual item correlations with total score on the Mood Disorder Questionnaire ranged from 0.50 to 0.75.

Figure 1 presents the sensitivity and the specificity for various threshold cutoffs of the total score. A Mood Disorder Questionnaire screening score of 7 or more was chosen as the optimal cutoff, as it provided good sensitivity (0.73, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.65–0.81) and very good specificity (0.90, 95% CI=0.84–0.96). Higher threshold cutoffs resulted in a loss of sensitivity without an appreciable increase in specificity; lower threshold cutoffs resulted in considerable loss of specificity. By using this 7-or-more-item threshold, seven out of 10 people with a bipolar spectrum disorder would be correctly identified by the Mood Disorder Questionnaire, whereas nine out of 10 of those who did not have a bipolar spectrum disorder would be successfully screened out.

Discussion

This study assessed the sensitivity and specificity of a brief, self-rated screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder by using a research diagnostic interview as the standard for diagnosis in a psychiatric outpatient population. The operating characteristics of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire are quite good and are comparable to those of other instruments that are used to screen for other psychiatric disorders. Mulrow et al. (8) reviewed 18 studies using nine different screening instruments for depression in primary care settings. The sensitivities and specificities of the instruments ranged from 0.67 to 0.99 (mean=0.84) and from 0.40 to 0.95 (mean=0.72), respectively. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire’s sensitivity of 0.73 and specificity of 0.90 compare well with the accuracy of these other instruments.

Further research is needed to assess whether the Mood Disorder Questionnaire would be useful in primary care, community agencies, and other psychiatric settings to identify individuals who might benefit from a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation.

Received March 1, 2000; revision received June 1, 2000; accepted June 7, 2000. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical Branch, the University of Texas at Galveston; the Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, and the New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York; the School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland; the National Association for the Mentally Ill, Washington, D.C.; the Biological Psychiatry Program, Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati; the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association, Chicago; the NIMH, Bethesda, Md.; Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston; and Rush-Presbyterian–St. Luke’s Medical Center, Chicago.Address reprint requests to Dr. Hirschfeld, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical Branch, University of Texas at Galveston, 1.302 Rebecca Sealy, 301 University Blvd., Galveston, TX 77555-0188; [email protected] (e-mail). Supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Abbott Laboratories.The authors thank David M. Medearis, B.S., for assistance in the preparation of this article.

|

Figure 1. Operating Characteristics of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire for Various Threshold Scores Among 198 Patients From Outpatient Mood Disorder Clinicsa

aA score of 7 or higher (gray vertical line) was chosen as the optimal cutoff.

bIn addition to achieving the threshold number of symptom items, the subject must also have indicated that the symptoms clustered in the same time period (“yes” on question 2) and caused moderate or serious problems (“moderate” or “serious” on question 3).

1. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Weissman MM, Bruce LM, Leaf PJ: Affective disorders, in Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Edited by Robins LN, Regier DA. New York, Free Press, 1991, pp 53–80Google Scholar

3. Klerman GL: The spectrum of mania. Compr Psychiatry 1981; 22:11–20Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Akiskal HS, Pinto O: The evolving bipolar spectrum: prototypes I, II, III, and IV. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1999; 22:517–534Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Angst J: The emerging epidemiology of hypomania and bipolar II disorder. J Affect Disord 1998; 50:143–151Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lish JD, Dime-Meenan S, Whybrow PC, Price RA, Hirschfeld RM: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association (National DMDA) survey of bipolar members. J Affect Disord 1994; 31:281–294Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:624–629Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Mulrow CD, Williams JW Jr, Gerety MB, Ramirez G, Montiel OM, Kerber C: Case-finding instruments for depression in primary care settings. Ann Intern Med 1995; 122:913–921Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar