Cost-Effectiveness of Services for Mentally Ill Homeless People: The Application of Research to Policy and Practice

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: About one-quarter of homeless Americans have serious mental illnesses. This review synthesizes research findings on the cost-effectiveness of services for this population and their relevance for policy and practice. METHOD: Service interventions for seriously mentally ill homeless people were grouped into three overlapping categories: 1) outreach, 2) case management, and 3) housing placement and transition to mainstream services. Data were reviewed both from experimental studies with high internal validity and from observational studies, which better reflect typical community practice. RESULTS: In most studies, specialized interventions are associated with significantly improved outcomes, most consistently in the housing domain, but also in mental health status and quality of life. These programs are also associated with increased use of many types of health service and housing assistance, resulting in increased costs in most cases. The value of these programs to the public thus depends on whether their greater effectiveness is deemed to be worth their additional cost. CONCLUSIONS: Innovative programs for seriously mentally ill homeless people are effective and are also likely to increase costs in many cases. Their value ultimately depends on the moral and political value society places on caring for its least-well-off members.

For the past two decades, over one-half million Americans, about one-quarter with severe mental illness, have been left homeless, living on city streets and sleeping in emergency shelters each night (1). At a time of unprecedented national affluence, when American psychiatry has generated remarkable scientific and clinical advances, we have failed to protect hundreds of thousands of seriously mentally ill citizens from drifting into homelessness. After almost two decades of research on homelessness and the recent publication of experimental studies, it is timely to review what we have learned and to consider the implications for policy and practice.

Homeless people with mental illness have exceptionally diverse housing and mental health needs. We therefore adopt a broad definition of the population that includes all persons who lack a fixed, regular nighttime abode and who experience clinically diagnosed psychiatric disorders. We exclude only studies involving programs for homeless people with primary addictive disorders.

In addition, because only three experimental cost-effectiveness studies have been published on this population, and few experimental studies have been conducted, we will need to add to our review of experimental studies with data from observational outcome studies that include cost data.

The goals of this review are both substantive and methodological. From the substantive point of view, we review recent research and summarize its implications for assisting a deeply disadvantaged and difficult-to-treat population. Methodologically, we demonstrate an approach to applying findings from diverse research studies to real-world policy making, an approach that addresses 1) the problem of generalizing from small, selected samples to large service populations; 2) the use of service utilization data to assess cost-effectiveness when important studies lack economic data; 3) the sensitivity of cost-effectiveness analysis to the specifics of program design and target population; and 4) the ultimate role of public values and attitudes in programmatic decision making, especially when empirical data suggest that treatment is associated with both increased benefits and increased costs.

Programs for Seriously Mentally Ill Homeless People

The housing and mental health problems of homeless people are typically complicated by poor physical health, past trauma, long-term poverty, social isolation, lack of vocational skills, and a stigmatizing involvement in the criminal justice system (2–4). As a result, programs that assist this population must provide a wide range of health, mental health, and rehabilitation services and must address material needs for housing subsidies and public support payments (5).

To organize our review, we distinguish between three types of programs based on three overlapping phases of treatment: 1) outreach services targeted at homeless people who are reluctant to seek help on their own, 2) case management services that rely on personalized relationships to facilitate access to services, and 3) housing placement and community mainstreaming efforts that provide links with long-term sources of residential support and health care service (Table 1).

Cost-Effectiveness of Services

Outreach Programs

New York Choices program

The only experimental study, to our knowledge, of an outreach program for mentally ill homeless persons is the New York Choices program (3), which is composed of four services: 1) outreach and engagement, 2) a low-demand day/drop-in center, 3) a 10-bed respite housing unit, and 4) community-based rehabilitation.

Over a 2-year follow-up period Choices clients experienced significantly greater access than control subjects to basic resources such as food and shelter; had significantly greater improvement in psychiatric symptoms and quality of life; and enjoyed a 54% reduction in nights sleeping on the street—almost twice the 28% reduction among control subjects (3).

Although direct cost data are not available from this study, the provision of respite beds and case management directly through the program generated costs that would be similar to those in assertive community treatment programs—several thousand dollars (8, 10, 17). In addition, data on nonprogram service use show that Choices clients were more likely than control subjects to have used eight of nine types of nonprogram health service, including inpatient mental health care. Thus, unlike intensive case management programs for high service users in which program costs are often offset by reduced use of inpatient services (17), Choices clients incurred increased costs for inpatient and other types of care in addition to the basic program costs and were therefore likely to have substantially greater total health costs than control subjects.

Access to Community Care and Effective Supportive Services Program

Although the evaluation of Choices showed that positive outcomes can follow successful outreach, it did not address either the considerable time and effort outreach workers often spend building rapport with clients before they enter treatment or the substantial expenditure of resources when outreach efforts do not result in entry into treatment.

Data from the Center for Mental Health Services’ 18-site Access to Community Care and Effective Supportive Services Program provide a fuller perspective on resource use in the outreach process (6). During the first 3 years of the Access to Community Care and Effective Supportive Services Program, a total of 11,857 clients were contacted at outreach, but only 5,431 (46%) entered case management. Those contacted in street settings were typically the sickest and most vulnerable, but only 34% expressed interest in services at the time of first contact, and only 19% eventually entered case management.

Once in case management, clients who had been contacted through street outreach improved in both clinical and housing domains, comparable to that of other program participants. However, their entry into the program was substantially more costly because 1) for each successful entrant, four candidates were screened who did not enter the program; and 2) the process of engagement took almost twice as long as for other clients (101 days versus 48 days). Failed encounters, which are an intrinsic part of the outreach endeavor, are thus likely to add substantially to the average cost for each client who is successfully engaged in treatment.

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) veterans program

Although neither of the previous studies included quantitative information on the cost of homeless outreach, extensive cost data are available from the VA’s Homeless Chronically Mentally Ill Veterans Program (7, 18), which includes three components: 1) community outreach, 2) broker model case management, and 3) time-limited residential treatment. As part of an economic evaluation of the Homeless Chronically Mentally Ill Veterans Program, comprehensive cost data were obtained for 1,748 Homeless Chronically Mentally Ill Veterans Program clients contacted at nine program sites (7, 18).

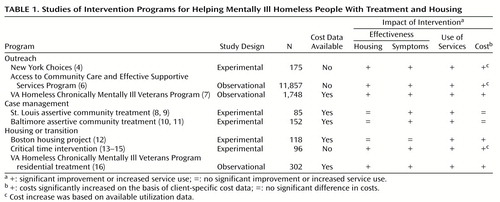

General VA health care costs, including inpatient and outpatient psychiatric and medical care, increased significantly, from $6,414 per patient per year in the year before the first outreach contact to $7,269 in the year after entry (Figure 1). When the Homeless Chronically Mentally Ill Veterans Program costs for case management ($315) and residential treatment ($1,115) are added, total costs to the VA in the year after the first outreach contact increased even further, to $8,699, a $2,285 (35.6%) increase over the previous year (7). These data show that, especially when effective, outreach can be costly. This is not surprising, since the very reason for conducting outreach is to enhance access to services for the underserved.

Case Management

Most case management programs for homeless people with mental illness have been modeled on the assertive community treatment model of Stein and Test (8, 10, 17) and emphasize 1) small caseloads, 2) service delivery through integrated, multidisciplinary teams in community settings, and 3) long-term involvement. In a recent literature review (19), Morse identified 10 experimental studies of case management programs that served homeless persons with mental illness. Two of these included economic evaluations and will be reviewed in detail shortly. Seven of 10 studies showed fewer homeless days for those assigned to case management, whereas two showed a significant reduction in symptoms.

Assertive community treatment versus broker case management

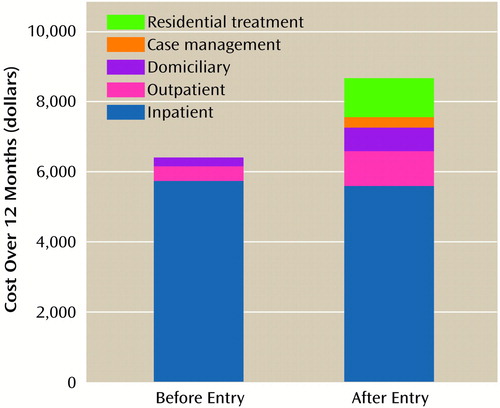

The first published cost-effectiveness study of case management for homeless people compared a broker case management intervention (in which emphasis is placed on linking clients to service providers) with two types of assertive community treatment programs, one with additional specially trained community workers and one without such workers (8, 20). Although the direct costs for both assertive community treatment models exceeded $9,000 per client over the 18-month study period, they were both also associated with substantially reduced inpatient costs (Figure 2). When all health care costs were added together, costs were lowest for assertive community treatment plus community workers ($39,913), highest for those receiving standard assertive community treatment ($49,510), and in the middle for clients in brokered case management ($45,076). These results replicate findings for assertive community treatment in other seriously mentally ill populations, showing that the high costs of case management can be at least partly offset by reduced hospital use (17).

Assertive community treatment clients in the St. Louis study had reduced symptoms and were more satisfied with the services they received than control subjects, although there were no differences in housing outcomes. This study suggests net cost neutrality for assertive community treatment and evidence of clinical superiority.

Assertive community treatment versus standard care

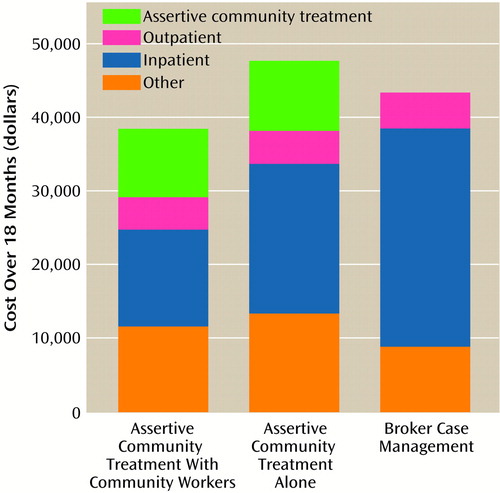

A second cost-effectiveness study of assertive community treatment (10) reported similarly high costs for assertive community treatment services ($8,244 per year) but also found substantially lower psychiatric inpatient costs for assertive community treatment clients in relation to control subjects ($31,427 versus $55,946) (Figure 3). As a result, total annual health care costs were about $16,000 lower for assertive community treatment subjects than for control subjects ($50,748 versus $66,479).

Assertive community treatment clients experienced greater improvements in symptoms, life satisfaction, and health status than control subjects and had more days in stable housing (9). As in the St. Louis study, significant benefits for assertive community treatment emerge in several domains and, because of reduced inpatient service use, total costs were not significantly different from those of control subjects. Together, these two studies suggest that after the high-cost outreach phase of treatment, assertive community treatment may be preferable to standard care, since it is both more effective than standard treatment and, because of reduced inpatient care, costs the same or less.

Experimental assertive community treatment studies

Although the experimental design of these two studies guarantees high internal validity, the generalizability of their findings requires further examination. The total cost impact of an expensive intervention can be profoundly affected by the overall level of service use and costs among study participants, since there is much room for savings with high-cost clients but little to save with low-cost clients (11, 17). Both the St. Louis and Baltimore studies included patients who incurred especially high inpatient costs.

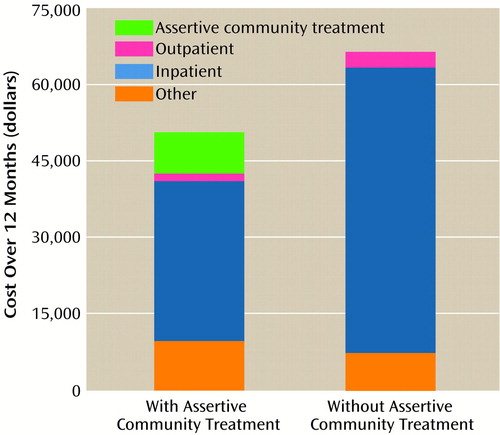

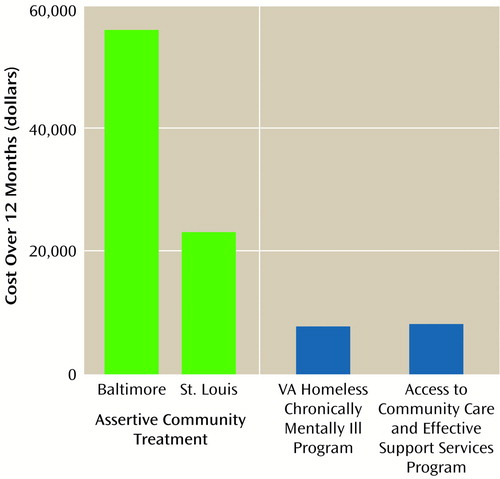

To estimate baseline inpatient costs in more typical programs, 12-month cost data from the VA’s Homeless Chronically Mentally Ill Veterans Program (7) and from the Access to Community Care and Effective Supportive Services Program were adjusted for inflation so they would be comparable to those from the St. Louis and Baltimore studies. Average annual inpatient costs were only $7,905 in the Homeless Chronically Mentally Ill Veterans Program and $8,346 in the Access to Community Care and Effective Supportive Services Program during the 1st year of treatment, less than one-third of the average annualized inpatient costs for control patients in the St. Louis and Baltimore studies (Figure 4). A review of the distribution of annual inpatient costs showed that at the 90th percentile, costs were $32,605 in the Homeless Chronically Mentally Ill Veterans Program and $25,010 in the Access to Community Care and Effective Supportive Services Program. Thus, in these two more representative programs, inpatient costs approached those of the St. Louis and Baltimore studies for only the most expensive 10% of clients, suggesting that these programs are likely to achieve cost neutrality for only a small segment of the total target population.

Housing and Transitional Services

The third segment in our overlapping continuum of services focuses on housing and the transition to mainstream community care.

Evolving consumer households versus independent living

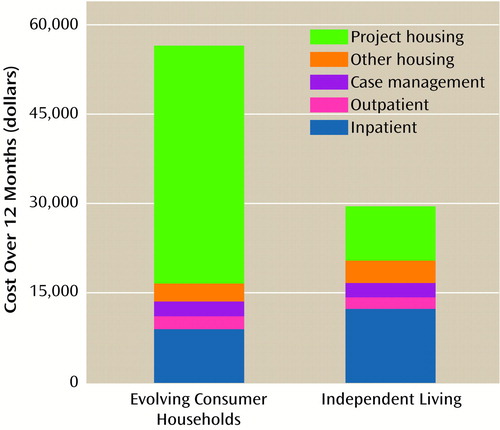

A cost-effectiveness study conducted in Boston evaluated evolving consumer households in which groups of consumers lived together, initially with substantial support from program staff. The goal of the evolving consumer household program was for consumers to develop mutually supportive communities that would eventually support themselves without staff assistance. A group of 118 clients were randomly assigned to either an evolving consumer household or to a more conventional independent-living condition that included placement in an apartment with off-site case management support (21).

Housing results were impressive for both groups, with evolving consumer household clients housed 92% of all nights and independent-living clients housed 83% of all nights—a nonsignificant difference. Improvement in health status and life skills, however, was more modest, ranging from 2% to 8% across measures, with no significant differences between groups.

Differences in total annual costs were substantial and significantly different, summing to $56,434 for the evolving consumer household group as compared to only $29,838 for the independent-living group. It is of interest that inpatient mental health costs in this study were modest, as in the Access to Community Care and Effective Supportive Services Program and the Homeless Chronically Mentally Ill Veterans Program, and favored the evolving consumer household group ($8,991 versus $12,519) (Figure 5), but they were not sufficient to offset the huge $42,829 annual supported housing costs associated with the evolving consumer household intervention.

Transition to community housing

The goal of specialized homeless service programs must ultimately be to transition clients into mainstream housing and mental health services. The critical time intervention was specifically designed to help homeless mentally ill clients in a shelter-based New York day program transition into permanent community residences and mainstream health care services (22). Critical time intervention consists of three phases: 1) an accommodation phase (months 1–3), in which critical time intervention workers conduct home visits and link clients with providers; 2) a try-out phase (months 4–7), in which clients begin to use mainstream services; and 3) a termination phase (months 8–9).

Over an 18-month follow-up period, critical time intervention clients spent an average of 30 nights homeless compared to 90 nights for control clients, a difference of 5.5% versus 16.6% of all nights (22), and demonstrated greater improvement in negative psychiatric symptoms (12).

Although cost data are not available directly from this study, service utilization data (23) show that (excluding critical time intervention services themselves) critical time intervention clients had more hospital days than control clients (41.8 versus 38.0), more emergency room visits (1.5 versus 1.2), more outpatient visits (29.7 versus 16.9), and more day program visits (73.8 versus 69.4) than control subjects. This intervention is thus likely to be associated with increased costs, especially after the costs of critical time intervention itself are included.

VA’s Homeless Chronically Mentally Ill Veterans Program

One of the most common approaches to community reentry for homeless people with mental illness is through time-limited treatment in a halfway house; one experimental study showed the effectiveness of such programs in improving both mental health and housing outcomes (24). Although this common approach has not yet been subject to an experimental cost-effectiveness study, 8-month follow-up and cost data are available from the VA’s Homeless Chronically Mentally Ill Veterans Program comparing 155 veterans who received an average of 99 days of contract residential treatment and 147 veterans who received case management services without any residential treatment (13).

Outcomes were generally superior among veterans in the residential treatment group, and general VA medical and mental health costs, exclusive of Homeless Chronically Mentally Ill Veterans Program costs, were not significantly different between those admitted to residential treatment ($9,053 per year) and those who were not ($8,205 per year). However, when special program costs for case management and residential treatment were included, costs for those admitted to residential treatment were $4,715 (53%) higher than for those who were not ($13,693 per year versus $8,978 per year). Homeless Chronically Mentally Ill Veterans Program contract residential treatment was thus associated with modestly better outcomes at 53% greater cost.

Discussion

This review of a diverse array of innovative programs suggests that although enhancing services for homeless people with mental illness generates significant benefits, costs may also increase, especially when outreach teams are used to contact the most vulnerable segments of the homeless population. This increase in service use and cost is not surprising, since these programs are designed to serve severely ill people with virtually no resources and poor access to services. The two studies that found that increased program costs may be offset by reduced inpatient costs focused on unusually heavy hospital users and thus apply to only a small segment of the target population. We thus observe that although they are generally effective, these programs can be cost-neutral or more expensive depending on the specifics of program design and target population.

As we consider the transition from these research results to policy and practice, two additional questions emerge: 1) what is the relationship of human service delivery and material support in the design of programs for homeless people with mental illness?; and 2) should society be willing to pay for services that are both more effective and more expensive?

Material Subsidies: Program Effectiveness Versus Jumping the Queue

Each of the programs reviewed above included a subsidized housing component as a central feature of the experimental treatment. Several programs also reported increased public support payments among their clients (8, 18), and one showed that increased public support was associated with superior housing outcomes (18). Since each of these programs had negotiated special access to housing resources, and one operated a joint outreach program with the Social Security Administration (14), they did not actually increase the available pool of resources. Rather, they helped their clients jump to the head of the line, displacing others who were probably just as deserving (25). To the extent that the effectiveness of augmented service programs is attributable to this queue-jumping function, dissemination of these programs will require increasing the availability of these resources. It is not surprising that effective service programs for homeless people include housing and income supports, but it is only when one moves from research to broader practice that the challenge of increasing the pool of such resources emerges as a major challenge and potential barrier to widespread dissemination.

Although some policy analysts have concluded that increasing housing and income supports should be the principal policy initiative for homeless people with mental illness (15, 26), the relative importance and likely interdependence of clinical services and material supports for this population is understudied and is an important area for future research.

Societal Willingness to Pay

Our review of research suggests that innovative programs for homeless people with mental illness are modestly more effective than standard care, but they may also be more expensive. Furthermore, we have suggested that in the transition from research to practice, these programs must incur additional costs to increase the available pool of housing subsidies and income supports. What, finally, are the implications of these cost-effectiveness data? What can we recommend to policy makers and program planners?

If we had found that these new treatment approaches were both more effective and less costly than conventional alternatives, our recommendation to implement them would have been straightforward and based entirely on research data. Our counsel would have been positive and definite: “If you invest in these programs, your clients will have better outcomes, and by redeploying funds from old models to new, you will save money with which you can treat additional clients.” This statement does appear to be justified in the case of assertive community treatment for the most resource-intensive 10% of clients.

Since most of the programs we have reviewed are likely to be both more effective and more costly for the typical client, the decision of whether they should be implemented depends on whether the value of these benefits equals their additional cost. In this situation, cost-effectiveness analysis, in which we compare the costs of unmonetized outcomes (e.g., dollars per day of reduced homelessness), is an incomplete guide to decision making. Rather, cost-benefit analysis is needed, in which the dollar value of health gains is estimated (16, 27) to determine whether they exceed costs.

Since it is the public that pays for these health benefits, the standard for determining their value is the public’s willingness to pay for them. Economists have developed two methods for empirically estimating societal willingness to pay for various public goods. The first method, revealed-preferences assessment (28, 29), attempts to extrapolate from goods and services that society pays for to those that are in question. For example, by using data on wage premiums for hazardous (i.e., life-endangering) employment, the value of a year of healthy life has been estimated at $20,000–$350,000 (27). If, using standard procedures, we could convert health improvements for homeless people to a measure equivalent to years of healthy life gained (quality-adjusted life years) (16, 27), we would be able to assign a monetary value to these health improvements.

In the second method, contingent valuation (28), representative samples of the general public are directly asked how much they would be willing to pay to achieve various personal or societal objectives, such as improving the situation of homeless people with mental illness. One study, for example, found that people were willing to pay $301 in 1999 inflation-adjusted dollars to avoid a day of incapacitating drowsiness (29). If we roughly equate the dysphoria of such a state with a day of homelessness, we could estimate that the reduction of 60 days of homelessness by critical time intervention would be worth $18,000, easily enough to pay for the program.

Although neither of these methods has been directly applied to the evaluation of programs for homeless people with mental illness, economic analysis of these programs would be substantially strengthened by careful research along these lines.

One final question remains to be addressed. What if it is determined that the benefits of the specific programs evaluated here are not worth their additional cost? Does this mean that programs for homeless people with mental illness are, in general, not cost-effective? Should the programs that are currently in operation be closed down? Are they a waste of taxpayers’ money? The simple answer to these questions is “no.” Research studies like those reviewed here focus on new technologies that may improve standard services, not to the standard services themselves. A decision that an augmented program should not be widely implemented because it does not generate enough benefit to justify its cost says nothing about the comparison of standard programs with the alternative of providing no services at all. That question could only be addressed by a study that compares current standard care with no care, a comparison that would be as unethical to conduct from the research point of view as it would be unacceptable as a deliberate policy in a compassionate society.

|

Presented in part at a workshop on the benefit-cost of homeless services, sponsored by the Center for Mental Health Services, Washington, DC, June 19–20, 1999. Received Aug. 6, 1999; revisions received Dec. 20, 1999, and March 27, 2000; accepted April 25, 2000. From the VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center and the Department of Psychiatry and the Department of Public Health, Yale Medical School, New Haven, Conn. Address correspondence to Dr. Rosenheck, VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center/182, 950 Campbell Ave., West Haven, CT 06516; [email protected] (e-mail).Supported in part by the Veterans Integrated Service Network 1 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center.The author thanks Barbara Dickey, Ph.D., Paul Errera, M.D., Daniel Herman, Ph.D., Wesley Kasprow, Ph.D., Paul Koegel, Ph.D., Anthony Lehman, M.D., Douglas Leslie, Ph.D., Nancy Wolfe, Ph.D., and several conference participants for comments on earlier versions of this article.

Figure 1. Health Care Costs Incurred Over 12 Months by Clients Before and After Entry Into the Department of Veterans Affairs Homeless Chronically Mentally Ill Veterans Program (7)

Figure 2. Health Care Costs Incurred Over 18 Months by Clients in the St. Louis Assertive Community Treatment Study (8)

Figure 3. Health Care and Societal Costs Incurred Over 12 Months by Clients in the Baltimore Assertive Community Treatment Study (10)

Figure 4. Inpatient Costs Incurred Over 12 Months by Control Clients Participating in the Baltimore (10) and St. Louis (8) Assertive Community Treatment Programs and Standard Clients in the Homeless Chronically Mentally Ill Veterans Program (7) and the Access to Community Care and Effective Support Services Program (R. Rosenheck, unpublished data)

Figure 5. Health and Housing Costs Incurred Over 12 Months by Clients in the Boston Evolving Consumer Households Housing Project (21)

1. Jencks C: The Homeless. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1994Google Scholar

2. Rossi P: Down and Out in America: The Causes of Homelessness. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1989Google Scholar

3. Shern D, Tsemberis S, Anthony W, Lovell AM, Richmond L: Serving street-dwelling individuals with psychiatric disabilities: outcomes of a psychiatric rehabilitation clinical trial. Am J Public Health (in press)Google Scholar

4. Lehman AF: A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 1988; 11:51–62Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Goldman HH, Morrissey JP: The alchemy of mental health policy: homelessness and the fourth cycle of reform. Am J Public Health 1985; 75:727–731Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lam JA, Rosenheck RA: Street outreach for homeless persons with serious mental illness: is it effective? Med Care 1999; 37:894–907Google Scholar

7. Rosenheck RA, Gallup PA, Frisman LK: Health care utilization and costs after entry into an outreach program for homeless mentally ill veterans. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1993; 44:1166–1171Google Scholar

8. Wolfe N, Helminiak TW, Morse GA, Calsyn RJ, Klinkenberg WD, Trusty ML: Cost-effectiveness evaluation of three approaches to case management for homeless mentally ill clients. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:341–348Link, Google Scholar

9. Lehman AF, Dixon LB, Kernan E, DeForge BR, Postrado LT: A randomized trial of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54:1038–1043Google Scholar

10. Lehman AF, Dixon L, Hoch JS, DeForge B, Kernan E, Frank R: Cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174:346–352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Rosenheck R, Cramer J, Allan E, Erdos J, Frisman LK, Xu W, Thomas J, Henderson W, Charney D (Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Clozapine in Refractory Schizophrenia): Cost-effectiveness of clozapine in patients with high and low levels of hospital use. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56:565–572Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Herman D, Opler L, Felix A, Valencia E, Wyatt RJ, Susser E: A critical time intervention with mentally ill homeless men: impact on psychiatric symptoms. J Nerv Ment Dis 2000; 188:135–140Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Rosenheck RA, Gallup PA, Frisman LK: The relationship of specific interventions to clinical improvement in the Homeless Chronically Mentally Ill Veterans Program, in Health Care for Homeless Veterans Programs: Sixth Annual Report. Edited by Frisman LK, Rosenheck RA. West Haven, Conn, VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 2000, pp 39–83Google Scholar

14. Rosenheck RA, Frisman LK, Kasprow W: Improving access to disability benefits among homeless persons with mental illness: an agency-specific approach to services integration. Am J Public Health 1999; 89:524–528Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Wright JD, Rubin BA, Devine JA: Beside the Golden Door: Policy, Politics and the Homeless. New York, Aldine de Gruyer, 1998Google Scholar

16. Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC: Cost Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

17. Rosenheck RA, Neale MS: Cost-effectiveness of intensive psychiatric community care for high users of inpatient services. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:459–466Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Rosenheck RA, Frisman LK, Gallup PG: Effectiveness and cost of specific treatment elements in a program for homeless mentally ill veterans. Psychiatr Serv 1995; 46:1131–1139Google Scholar

19. Morse G: A review of case management for people who are homeless: implications for practice, policy and research, in Practical Lessons: The 1998 National Symposium on Homelessness Research. Edited by Fosburg LB, Dennis DL. Washington, DC, US Department of Housing and Urban Development, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999, pp 7-1–7-34Google Scholar

20. Morse GA, Calsyn RJ, Allen G, Templehoff B, Smith R: Experimental comparison of the effects of three treatment programs for homeless mentally ill people. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1992; 43:1005–1010Google Scholar

21. Dickey B, Latimer E, Powers K, Gonzalez O, Goldfinger SM: Housing costs for adults who are mentally ill and formerly homeless. J Ment Health Admin 1997; 24:291–305Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Susser E, Valencia E, Conover S, Felix A, Tsai WY, Wyatt RJ: Preventing recurrent homelessness among mentally ill men: a “critical time” intervention after discharge from a shelter. Am J Public Health 1997; 87:256–262Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Jones K, Colson P, Valencia E, Susser E: A preliminary cost effectiveness analysis of an intervention to reduce homelessness among the mentally ill. Psychiatr Q 1994; 65:243–256Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Lipton FR, Nutt S, Sabatini A: Housing the homeless mentally ill: a longitudinal study of a treatment approach. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1988; 39:40–45Abstract, Google Scholar

25. Shinn M, Baumohl J: Rethinking the prevention of homelessness, in Practical Lessons: The 1998 National Symposium on Homelessness Research. Edited by Fosburg LB, Dennis DL. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999, pp 13-1–13-36Google Scholar

26. Sosin MR, Grossman S: The mental health system and the etiology of homelessness: a comparison study. J Community Psychol 1991; 19:337–350Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Weinstein MC: From cost-effectiveness ratios to resource allocation: where to draw the line, in Valuing Health Care. Edited by Sloan FA. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp 77–97Google Scholar

28. Johanneson M: Theory and Methods of Economic Evaluation of Health Care. Dordrecht, the Netherlands, Kluwer Academic, 1996Google Scholar

29. Viscusi WK: Fatal Tradeoffs: Public and Private Responsibilities and Risk. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar