Memory Impairment in Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Memory impairment is well documented in schizophrenia. Less is known, however, about the exact magnitude, pattern, and extent of the impairment. The effect of potential moderator variables, such as medication status and duration of illness, is also unclear. In this article, the authors presented meta-analyses of the published literature on recall and recognition memory performance between patients with schizophrenia and normal comparison subjects. METHOD: Meta-analyses were conducted on 70 studies that reported measures of long-term memory (free recall, cued recall, and recognition of verbal and nonverbal material) and short-term memory (digit span). Tests of categorical models were used in analyses of potential moderators (clinical variables and study characteristics). RESULTS: The findings revealed a significant and stable association between schizophrenia and memory impairment. The composite effect size for recall performance was large. Recognition showed less, but still significant, impairment. The magnitude of memory impairment was not affected by age, medication, duration of illness, patient status, severity of psychopathology, or positive symptoms. Negative symptoms showed a small but significant relation with memory impairment. CONCLUSIONS: This meta-analysis documented significant memory impairment in schizophrenia. The impairment was stable, wide ranging, and not substantially affected by potential moderating factors such as severity of psychopathology and duration of illness.

During the last several decades, evidence has accumulated that schizophrenia is associated with significant impairment in cognitive functioning. Specifically, deficits in attention, memory, and executive function have been consistently reported in patients with schizophrenia (1–3). In contrast, formal assessment of perceptual processes and basic language function does not show gross impairment (3). Memory has been regarded as one of the major areas of cognitive deficit in schizophrenia (4). Although the pioneers of schizophrenia research, Kraepelin (5) and Bleuler (6), considered memory functions to be relatively preserved in schizophrenia, numerous studies conducted in the second half of this century have shown that patients with schizophrenia perform poorly on a wide range of memory tasks (3, 7, 8). Studies indicate memory impairment in schizophrenia to be common and disproportionate to the overall level of intellectual impairment (9, 10). McKenna and colleagues (11) have even suggested existence of a schizophrenic amnesia.

However, other authors consider the memory impairment to be relatively small in magnitude or secondary to attentional dysfunction (12–15). In addition, the specificity of memory impairment in schizophrenia is unclear. It has been suggested that, in schizophrenia, some aspects of memory may be affected to a greater extent than others. This would be the case, for example, in active retrieval (free recall) of declarative information from long-term memory, which would be significantly more impaired in individuals with schizophrenia than retrieval from short-term memory—e.g., digit span (16). Also, some authors have proposed that encoding of information may be more affected than memory processes such as retrieval and recognition (17, 18). In contrast, other studies report that the memory deficit in schizophrenia encompasses a broad range of memory processes, as evidenced by poor scores in multiple task paradigms (7, 10, 19, 20).

Other important issues regarding schizophrenia and memory performance that remain unclear are whether memory functioning in schizophrenia is stable over time, whether chronic patients with schizophrenia exhibit greater memory impairment than acutely ill patients, and whether the effects of medication may account for a significant portion of the observed memory impairment.

Meta-analysis represents a type of review that applies a quantitative approach with statistical standards comparable to primary data analysis. A meta-analytical approach has several advantages above traditional narrative methods of review. By quantitatively combining the results of a number of studies, the power of the statistical test is increased substantially. Also, studies are differentially weighted with varying group size. Finally, by extracting information quantitatively from existing studies, meta-analysis allows one to examine more precisely the influence of potential moderators of effect size.

The aim of the present study was twofold. The first goal was to determine the magnitude, extent, and pattern of memory impairment in schizophrenia by meta-analytically synthesizing the data from studies published during the past two decades. The second purpose was to examine the effect of potential moderator variables, such as clinical variables (e.g., age, patient status, and medication) and study characteristics (e.g., matching of comparison subjects and year of publication), on the association between schizophrenia and memory impairment.

METHOD

Literature Search

Articles for consideration were identified through an extensive literature search in PsycLIT and MEDLINE from 1975 through July 1998. The key words were “memory” and “schizophrenia.” The search produced over 750 unique studies. Titles and abstracts of the articles were examined for possible inclusion in our analysis. Additional titles were obtained from the bibliographies of these articles and from a journal-by-journal search for all of 1997 and the first half of 1998 for journals that we suspected most frequently publish articles in the targeted domain. This strategy was adopted to minimize the possibility of overlooking studies that may not yet have been included in computerized databases. The journals included the following: American Journal of Psychiatry, Archives of General Psychiatry, Journal of Abnormal Psychology, Psychological Medicine, Schizophrenia Bulletin, and Schizophrenia Research.

The identified studies had to meet the following inclusion criteria. First, each study had to include valid measures of explicit memory performance. We included the following paradigms: digit span (forward and backward), cued and free list recall and word list recognition, paired-associate recall, prose recall, and nonverbal (visual pattern) recall and recognition. Second, studies had to compare the performance of healthy normal comparison subjects with the performance of patients with schizophrenia. Studies with a comparison group consisting of nonpsychotic subjects with a higher risk for schizophrenia (e.g., first-degree relatives or subjects with schizotypal traits) were not included in the analyses. Finally, studies had to include sufficient data for the computation of a d value, which implies that means and standard deviations, exact p values, t values, or exact F values and relevant means should be reported. We obtained the results of 70 studies (9, 10, 15, 16, 19–84) that met the criteria for inclusion in our meta-analysis.

Data Collection and Analysis

By comparing measures of free recall, cued recall, and recognition, we examined the effect of retrieval support on memory performance between patients with schizophrenia and normal comparison subjects. In free recall measures, retention is measured in the absence of any cues, whereas in cued recall tests, a portion of the encoding context is presented at the time of retrieval. In recognition, the target material is presented along with distracters, and the subject is required to differentiate between target material and distracters. The learning curve refers to the increase in recall of information with different learning trials. Furthermore, we investigated the influence of the nature of the stimuli used in the memory tasks (verbal versus nonverbal). Finally, we evaluated the role of the retention interval, which could be assessed immediately after presentation of the to-be-learned material or after a delay.

From the data reported in each study, we calculated effect sizes for the difference in memory performance between patients with schizophrenia and comparison subjects. The effect size estimate used was Hedges’s g (85), the difference between the means of the schizophrenic group and the comparison group, divided by the pooled standard deviation. From these g values, an unbiased estimation, d, was calculated to correct for upwardly biased estimation of the effect in small group sizes (85, 86). The direction of the effect size was positive if the performance of the patients with schizophrenia on memory measures was worse than that of the comparison subjects.

The combined d value is an indication of the magnitude of associations across all studies. In addition to d, we calculated another statistic, Stouffer’s z, weighted by group size, with a corresponding probability level (86). This statistic provided an indication of the significance of the difference between memory performance in the schizophrenic group and the comparison group and thus indicated whether the results could have arisen by chance. We also calculated a chi-square statistic, Q, indicating the homogeneity of results across studies (87). The significance of the Q statistic pointed to the heterogeneity of the set of studies, in which case a further search of moderator variables was needed. In the moderator analyses, QW denoted the heterogeneity of studies within categories. The QB statistic refers to a test of differences between categories. This between-group homogeneity statistic is analogous to the F statistic. All analyses were performed with the statistical package META (88).

When more than one dependent measure was used as an indication of memory performance, a pooled effect size was computed to prevent data from one study from dominating the outcome of the overall meta-analysis. For example, in studies reporting data on free and cued recall of verbal and nonverbal stimuli, for each study, a combined d was calculated for inclusion in the overall analysis. However, in subsequent analyses, we included only the data pertaining to the specific category of our aim. Thus, for example, in the meta-analysis of differences between patients with schizophrenia and comparison subjects in cued recall performance, only data of cued recall measures were included in the analysis. Similarly, when a study reported data for subgroups such as patients with first-episode schizophrenia versus patients with chronic schizophrenia, in the overall analysis, the d values were pooled, but in the moderator analysis of duration of illness, the d values were included separately in the analysis.

In the case of twin studies (e.g., Goldberg et al. [48]), the patients were compared with normal twins. Thus, the unaffected siblings of identical twins discordant for schizophrenia were not included in the analyses. Furthermore, in studies in which data were reported for different subgroups (e.g., men/women, paranoia/nonparanoia), data were pooled across subgroups, which were then compared as one group with the performance of the comparison group.

When we encountered different studies in which data concerning the same group of subjects were reported, only one of the studies was included in the analysis to avoid the problem of dependent data (i.e., to prevent one group from dominating the outcome). For example, the subjects of the 1990 study by Goldberg et al. (89) were included in their 1993 study (48) as well. We included only the 1993 study (48) in the analysis because the group in that study contained more subjects than the group in the 1990 study (89).

Publication Bias

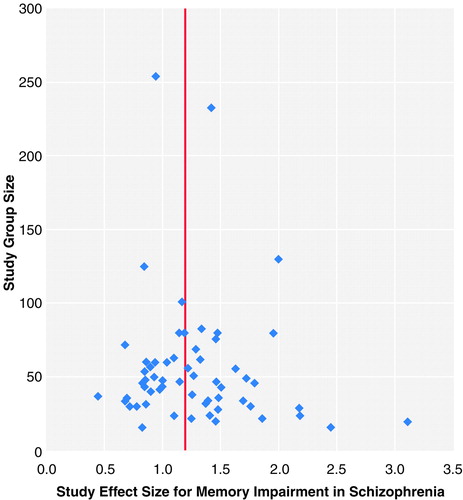

To examine the possibility of publication bias, we computed a fail-safe number of studies (86, 90). Publication bias implies that studies with no effect may not be published and may remain in file drawers, posing a threat to the stability of the obtained effect size. The fail-safe number of studies statistic indicates the number of studies with null effects that must reside in file drawers before the results of the obtained effect sizes are reduced to a negligible level (which we set at 0.2). Publication bias can also be inspected graphically in a funnel plot (91). The total group size of each study is plotted with its effect size. Because larger studies have more influence on the population effect size, small studies should be randomly scattered about the central effect size of larger studies. Thus, scatter will increase when study size decreases, which gives rise to an inverted funnel appearance. When the portion of the funnel near effect size 0.0 is not present, it may be an indication of publication bias because studies with nonsignificant effects and small group sizes remain unpublished.

Moderator Variables

The literature suggests a number of variables that may affect the memory performance of patients with schizophrenia. We evaluated the potential influence on effect size of several such factors, using categorical models. The moderator variables we studied can be divided into two groups: clinical variables and study characteristics. The clinical variables included age of subjects, patient status (inpatient or outpatient), medication status, duration of illness, severity of psychopathology, and the influence of positive and negative symptoms. For the analysis of severity of psychopathology, we included only studies reporting Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale scores. Other psychopathology measures, such as the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale, were not included because of a lack of studies. For positive and negative symptoms, the scales included in the analysis were the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms and the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms. The groups were divided by means of a median split.

Study characteristics were year of publication (before and after 1986, the median year of the period covered in the literature search), group size, and whether schizophrenic and comparison groups were matched for age and level of education. Unfortunately, sex differences, differential performance of diagnostic subgroups (e.g., paranoia/nonparanoia), task difficulty and reliability, and the moderating effects of attentional dysfunction could not be studied, because of the very small number or total lack of studies reporting exact results for these parameters.

RESULTS

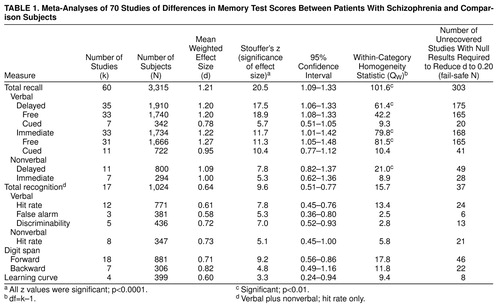

Table 1 displays the results of meta-analyses of schizophrenia and comparison group differences in performance on several memory measures: verbal and nonverbal, cued and free recall, delayed and immediate; verbal and nonverbal recognition; short-term memory (digit span); and encoding (learning curve).

Combined Schizophrenia-Memory Effect Sizes

As shown in Table 1, memory is significantly impaired in schizophrenia. All analyses yielded highly significant z values for the difference in memory performance between patients with schizophrenia and comparison subjects. The magnitude of the overall effect size of the composite long-term recall measures was large—d=1.21. In this overall analysis, 60 studies were included, with a total group size of 3,315 (with study groups ranging in size from N=16 to N=254). Effect sizes ranged from 0.44 to 3.10. The homogeneity statistic showed significant heterogeneity among studies. The funnel plot (figure 1) demonstrates the characteristic inverted funnel. However, the lower left portion of the funnel is less pronounced than the right, suggesting some bias in not publishing small studies with no effect. The fail-safe number of studies, at a critical d of 0.20, was 303. This implied that 303 unpublished null-effect studies were required to reduce our effects to a size of 0.20. The fail-safe numbers of studies for the other analyses were also large enough to lend credence to our findings.

Analyses of short-term memory (digit span) and encoding also revealed significant memory impairment, although to a considerably lesser degree than for recall measures. The difference between forward (d=0.71) and backward (d=0.82) digit spans was not significant (QB=0.6, df=1).

Effects of Task Characteristics

Patients with schizophrenia showed significantly better memory performance when retrieval cues were provided, as evidenced by the d of 1.20 in delayed free recall versus the d of 0.78 in cued recall (QB=11.6, df=1, p<0.001). However, the difference in performance on cued recall measures between normal subjects and patients with schizophrenia remained considerable. Recognition performance also showed significantly less impairment than recall performance (QB=58.1, df=1, p<0.0001), but the difference between patients’ and comparison performance remained substantial (d=0.64). As shown in Table 1, the QW statistics indicate homogeneous within-category d values.

Verbal and nonverbal recall scores both showed significant d values (p<0.0001). Although impairment for verbal material in the delayed recall condition (d=1.20) seemed larger than for nonverbal material (d=1.09), this difference was not significant. This was also the case for the immediate condition. For the recognition measures, the reverse pattern was observed: retrieval of verbal material (d=0.61) appeared to be less impaired than retrieval of nonverbal material (d=0.73), but again, the difference did not reach significance.

The length of the retention interval did not affect the magnitude of the d values. The difference between delayed (d=1.20) and immediate (d=1.22) verbal recall scores was not significant.

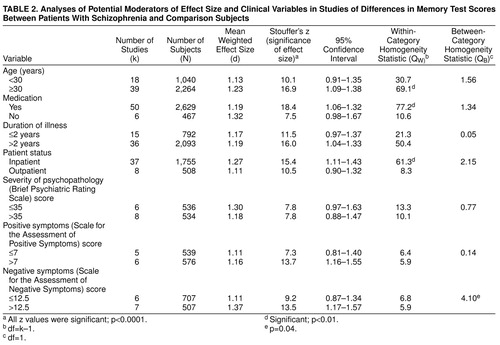

Potential Moderators of Effect Size

Table 2 shows the influence of potential moderator variables. The QB statistic revealed a significant effect only of negative symptoms (QB=4.0, df=1, p<0.05). Negative symptoms affected memory performance negatively. Age was not associated with memory impairment in schizophrenia in the categorical analysis. We also examined the exact correlation between age and d values, which was nonsignificant (r=0.14, N=57). Although in the categorical analyses, the two groups differed significantly in age (p<0.001), the range of the group ages as a whole was rather restricted (mean=32.4 years, SD=5; range=15.7–42.8).

Medication status, duration of illness, severity of psychopathology, and positive symptoms were not associated with memory impairment. For duration of illness, it was not possible to calculate a correlation coefficient because a great number of studies did not report exact values, and studies differed in their definitions of disease onset. For the other parameters, the number of studies was too small to meaningfully interpret the r value.

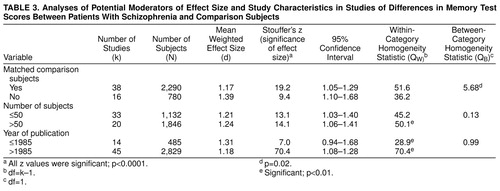

Studies that did not match comparison subjects for age and education showed a greater association between schizophrenia and poor memory performance than matched comparison studies (QB=5.68, df=1, p=0.02). Notwithstanding, the d for the matched comparison studies remained considerable—d=1.17. For the other study characteristics, the number of subjects and year of publication, no relation was found with d values (table 3).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether and to what extent schizophrenia is associated with memory impairment and whether this association is influenced by potential moderator variables. The results of the meta-analysis indicate that schizophrenia and memory dysfunction are significantly associated, as evidenced by moderate to large effect sizes. Our meta-analysis corroborates and extends the findings of a recent meta-analysis (92), in which performance on multiple measures of neurocognitive function was contrasted between patients with schizophrenia and normal comparison subjects. With regard to differences in memory performance, Heinrichs and Zakzanis (92) also reported moderate to large effect sizes for the memory variables they studied, which included verbal and nonverbal long-term memory.

The d for recall was 1.21, which indicated a large effect size, according to the nomenclature of Cohen (93). Thus, the performance of patients with schizophrenia was more than 1 standard deviation lower than that of normal comparison subjects on tasks of recall memory. A recent meta-analysis of memory impairment in depression (94) revealed a d of 0.56 (54 studies) for the recall performance of patients with depression compared with normal subjects. When these results are compared with our present analysis, the memory deficit in schizophrenia appears to be substantially greater than in depression. The d for recognition was 0.64, which can be considered a moderate effect size (93). The difference in recall versus recognition performance may point to a retrieval deficit, in addition to a less effective consolidation of material. Alternatively, the recall-recognition difference may be an artifact of the differences in difficulty between the recall and recognition tests. However, studies in which tasks were matched for difficulty level also showed greater impairment in recall than recognition (34, 35). The finding of a considerable memory deficit in schizophrenia supports the view that memory belongs to the cognitive domains, which show major impairment in schizophrenia (3, 4). However, the lack of difference between immediate and delayed recall does not appear to be in accordance with schizophrenia as an amnesic syndrome (11). Measures of short-term memory performance showed significant impairment. This result appears to contradict the assertion by Clare et al. (41) that short-term memory is preserved in schizophrenia. The divergence may result from the fact that Clare et al. based their conclusion on one study only, whereas the present study concerns a quantitative integration of multiple studies. Furthermore, our meta-analysis provides evidence that the learning curve (which reflects explicit encoding of information) is significantly affected in schizophrenia. The large difference between recall of information after a delay (composite delayed recall: d=1.20) and recall in the learning curve (d=0.60) suggests that the memory dysfunction in schizophrenia is not entirely caused by deficient learning processes (as was argued by Heaton et al. [17]) but that retrieval processes may also be affected. However, caution is needed in interpreting this finding, considering that digit span and learning curve indices may not reflect all encoding processes.

The results failed to reveal a difference in memory impairment between verbal and nonverbal (visual pattern) stimuli. Thus, the memory impairment in schizophrenia does not appear to be modality specific.

The present meta-analysis indicates memory impairment in schizophrenia to be wide ranging and consistent across task variables, such as level of retrieval support (free recall, cued recall, or recognition), stimulus type (verbal versus nonverbal), and retention interval (immediate versus delayed). The extent of the memory impairment may appear to be in accordance with a pattern of generalized dysfunction rather than a differential deficit (26). However, our study was restricted to memory functions, whereas conclusions regarding the generalized versus differential nature of neurocognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia must also include evaluation of functioning in other cognitive domains. Indeed, the recent meta-analysis by Heinrichs and Zakzanis (92), in which schizophrenia and comparison group differences were indexed on multiple measures of memory, attention, intelligence, executive function, language, and motor performance, indicated that schizophrenia is characterized by a broadly based cognitive impairment, with varying degrees of deficit in the different ability domains.

On the basis of our results, it is not possible to establish the cause or underlying mechanism of the memory impairment in schizophrenia. For example, we were not able to examine the moderating effects of attentional dysfunction. However, given the magnitude and extent of the memory impairment revealed by the meta-analysis, the possibility that the memory impairment may be secondary to attentional dysfunction does not seem very plausible. Moreover, in cases of an important attentional contribution to the memory impairment, one would expect performance on the backward digit span test to show a significantly greater impairment than that on the forward digit span test. This was not the case, however. Our findings are in agreement with those of Kenny and Meltzer (57), who controlled for the influence of attention by an analysis of covariance. Controlling for attention had very little effect on the differences in performance on long-term memory recall between patients with schizophrenia and comparison subjects.

Although the meta-analysis did not address the relation between memory impairment and brain pathology in schizophrenia, the pattern of impairment may be indicative of specific brain dysfunction. Impairments in encoding and consolidation have been associated with hippocampal and temporal lobe dysfunction (95, 96). Brain imaging studies have provided evidence for pathology or reduced volume in these structures in schizophrenia (97). In addition, frontal lobe systems, which may also be affected in schizophrenia, have been shown to be involved in the active retrieval of declarative memories (98, 99). More research into the relation between brain dysfunction and memory impairment in schizophrenia is needed before firm conclusions can be drawn on this issue.

Of the potential moderator variables, only negative symptoms affected the schizophrenia-memory association. Although this effect was rather small, it was consistent with previous research examining the relation between negative symptoms and cognitive function in schizophrenia (100, 101). Specifically, negative symptoms have been associated with more pronounced frontal lobe dysfunction, which may account for larger retrieval deficits (101). No relation was found between age and the magnitude of memory impairment. Unfortunately, because all subjects included in the analyses were less than 45 years old, no conclusions can be made regarding the relation between cognitive aging and memory in schizophrenia.

Clinical variables such as medication, duration of illness, patient status, severity of psychopathology, and positive symptoms did not appear to influence the magnitude of memory impairment. Thus, the memory impairment in schizophrenia is of a considerable robustness and is not readily moderated by variables that may seem relevant. This is an important finding, because a number of authors have emphasized the role of medication, symptom severity, and chronicity in the memory performance of patients with schizophrenia (8, 27). Frith (102) even suggested that medication may principally account for the memory deficits observed in schizophrenia. It is instructive to note that our meta-analysis does not address the relation between medication and memory performance directly but compares the performance of unmedicated groups with that of medicated groups. Differences in medication status may be caused by unspecified differences in clinical factors. Our results are consistent, however, with studies examining this relation directly, by experimentally controlling for medication use (103, 104). It must be emphasized that medication in the studies in our analysis consisted of conventional neuroleptics. Evidence is emerging that novel antipsychotics may have beneficial effects on memory function (105).

As the present meta-analysis demonstrates, there is no evidence of progressive decline associated with age or duration of illness in schizophrenia. Our failure to find an effect of chronicity on memory impairment is in accordance with the view of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia as a static encephalopathy (47). The fact that patients with schizophrenia with a long duration of illness do not perform worse than more acutely ill patients on memory tasks implies that the concept of dementia praecox (5) may not be accurate in the sense of progressive deterioration during the long-term course of the illness. On the other hand, considering the substantial memory deficit in schizophrenia revealed by our analysis, the term “dementia praecox” may be even more appropriate than Kraepelin himself may have anticipated.

The findings of our meta-analysis have important clinical implications. The substantial memory deficit in schizophrenia is likely to have repercussions on therapy and rehabilitation. A thorough understanding of the cognitive deficits in schizophrenia may prevent the failure of future treatments (106). For example, insight-related or other therapies that require advanced learning and memory functions are almost certain to be ineffective.

The extent and stability of the association between schizophrenia and memory impairment suggest that the memory dysfunction may be a trait rather than a state characteristic. Hypothetically, some degree of memory dysfunction may already be present in subjects at risk for schizophrenia. Future research must concentrate on this issue to explore the possible implications with regard to prescreening for schizophrenia.

There is evidence that verbal memory is a rather strong predictor of functional outcome in schizophrenia (107). Improving memory may be beneficial for everyday functioning. Therefore, given the considerable memory impairment revealed by our meta-analysis, research focusing on pharmacological treatment and rehabilitation strategies to improve memory functioning in patients with schizophrenia is necessary.

Received Sept. 8, 1998; revision received Feb. 8, 1999; accepted Feb. 23, 1999. From the Psychological Laboratory, Utrecht University; and the Department of Psychiatry, University Hospital Utrecht. Address reprint requests to Mr. Aleman, Psychological Laboratory, Department of Psychonomics, Utrecht University, Heidelberglaan 23584 CS Utrecht, the Netherlands; [email protected] (e-mail)

|

|

|

FIGURE 1. Funnel Plot for the Meta-Analysis of Composite Recall Measures in 60 Studies of Differences in Memory Test Scores Between Patients With Schizophrenia and Comparison Subjectsa

Each point represents the position of a single study. The vertical line indicates the mean weighted effect size.

1. Pantelis C, Nelson HE, Barnes TRE (eds): Schizophrenia: A Neuropsychological Perspective. Chichester, UK, John Wiley & Sons, 1996Google Scholar

2. Bilder RM: Neuropsychology and neurophysiology in schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 1996; 9:57–62Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Goldberg TE, Gold JM: Neurocognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia, in Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. Edited by Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ. New York, Raven Press, 1995, pp 1245–1257Google Scholar

4. McKenna P, Clare L, Baddeley AD: Schizophrenia, in Handbook of Memory Disorders. Edited by Baddeley AD, Wilson BA, Watts FN. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1995, pp 271–292Google Scholar

5. Kraepelin E: Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia (1919). Translated by Barclay RM; edited by Robertson GM. New York, Robert E Krieger, 1971Google Scholar

6. Bleuler E: Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias (1911). Translated by Zinkin J. New York, International Universities Press, 1950Google Scholar

7. Landrø NI: Memory function in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1994; 384:87–94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Stip E: Memory impairment in schizophrenia: perspectives from psychopathology and pharmacotherapy. Can J Psychiatry 1996; 41(suppl 2):27S–34SGoogle Scholar

9. Gold JM, Randolph C, Carpenter CJ, Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR: Forms of memory failure in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol 1992; 101:487–494Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Rund BR: Distractibility and recall capability in schizophrenics: a 4 year longitudinal study of stability in cognitive performance. Schizophr Res 1989; 2:265–275Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. McKenna PJ, Tamlyn D, Lund CE, Mortimer AM, Hammond S, Baddeley AD: Amnesic syndrome in schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1990; 20:967–972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Cutting J: The Psychology of Schizophrenia. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingstone, 1985Google Scholar

13. Nuechterlein KH, Dawson ME: Information processing and attention in the development of schizophrenic disorders. Schizophr Bull 1984; 10:160–203Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Gjerde P: Attentional capacity dysfunction and arousal in schizophrenia. Psychol Bull 1983; 93:57–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Culver LC, Kunen S, Zinkgraf SA: Patterns of recall in schizophrenics and normal subjects. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986; 174:620–623Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Koh SD, Marusarz TZ, Rosen AJ: Remembering of sentences by schizophrenic young adults. J Abnorm Psychol 1980; 89:291–294Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Heaton R, Paulsen JS, McAdams LA, Kuck J, Zisook S, Braff D, Harris MJ, Jeste DV: Neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenics; relationship to age, chronicity and dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:469–476Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. McClain L: Encoding and retrieval in schizophrenic free recall. J Nerv Ment Dis 1983; 171:471–479Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Calev A, Venables PH, Monk AF: Evidence for distinct verbal memory pathologies in severely and mildly disturbed schizophrenics. Schizophr Bull 1983; 9:247–263Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Saykin AJ, Gur RC, Gur RE, Mozley D, Mozley LH, Resnick SM, Kester DB, Stafiniak P: Neuropsychological function in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:618–624Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Abbruzzese M, Scarone S: Memory and attention dysfunctions in story recall in schizophrenia: evidence of a possible frontal malfunctioning. Biol Psychol 1993; 35:51–58Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Albus M, Hubmann W, Mohr F, Scherer J, Sobizack N, Franz U, Hecht S, Borrmann M, Wahlheim C: Are there gender differences in neuropsychological performance in patients with first-episode schizophrenia? Schizophr Res 1997; 28:39–50Google Scholar

23. Bauman E, Kolisnyk E: Interference effects in schizophrenic short-term memory. J Abnorm Psychol 1976; 85:303–308Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Bazin N, Perruchet P: Implicit and explicit associative memory in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1996; 22:241–248Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Binder J, Albus M, Hubmann W, Scherer J, Sobizack N, Franz U, Mohr F, Hecht S: Neuropsychological impairment and psychopathology in first-episode schizophrenic patients related to the early course of illness. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998; 248:70–77Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Blanchard JJ, Neale JM: The neuropsychological signature of schizophrenia: generalized or differential deficit? Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:40–48Google Scholar

27. Bornstein RA, Nasrallah HA, Olson SC, Coffman JA, Torello M, Schwarzkopf SB: Neuropsychological deficit in schizophrenic subtypes: paranoid, nonparanoid, and schizoaffective subgroups. Psychiatry Res 1990; 31:15–24Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Braff DL, Heaton R, Kuck J, Cullum M, Moranville J, Grant I, Zisook S: The generalized pattern of neuropsychological deficits in outpatients with chronic schizophrenia with heterogeneous Wisconsin Card Sorting Test results. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:891–898Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Brebion G, Smith MJ, Gorman JM, Amador X: Discrimination accuracy and decision biases in different types of reality monitoring in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:247–253Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Brebion G, Amador X, Smith MJ, Gorman JM: Mechanisms underlying memory impairment in schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1997; 27:383–393Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Broga MI, Neufeld RWJ: Multivariate cognitive performance levels and response styles among paranoid and nonparanoid schizophrenics. J Abnorm Psychol 1981; 90:495–509Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Buchanan RW, Strauss ME, Kirkpatrick B, Holstein C, Breier A, Carpenter WT: Neuropsychological impairments in deficit vs nondeficit forms of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:804–811Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Buckley PF, Moore C, Long H, Larkin C, Thompson P, Mulvany F, Redmond O, Stack JP, Ennis JT, Waddington JL:1H-Magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the left temporal and frontal lobes in schizophrenia: clinical, neurodevelopmental, and cognitive correlates. Biol Psychiatry 1994; 36:792–800Google Scholar

34. Calev A: Recall and recognition in mildly disturbed schizophrenics: the use of matched tasks. Psychol Med 1984; 14:425–429Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Calev A: Recall and recognition in chronic nondemented schizophrenics: use of matched tasks. J Abnorm Psychol 1984; 93:172–177Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Calev A, Berlin H, Lerer B: Remote and recent memory in long-hospitalized chronic schizophrenics. Biol Psychiatry 1987; 22:79–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Calev A, Nigal D, Kugelmass S, Weller MP, Lerer B: Performance of long-stay schizophrenics after drug withdrawal on matched immediate and delayed recall tasks. Br J Clin Psychol 1991; 30:241–245Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Calev A, Edelist S, Kugelmass S, Lerer B: Performance of long-stay schizophrenics on matched verbal and visuospatial recall tasks. Psychol Med 1991; 21:655–660Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Cannon T, Zorrilla LE, Shtasel D, Gur RE, Gur RC, Marco EJ, Moberg P, Price RA: Neuropsychological functioning in siblings discordant for schizophrenia and healthy volunteers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:651–661Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Cantor-Graae E, Warkentin S, Nilsson A: Neuropsychological assessment of schizophrenic patients during a psychotic episode: persistent cognitive deficit? Acta Psychiatr Scand 1995; 91:283–288Google Scholar

41. Clare L, McKenna PJ, Mortimer AM, Baddeley AD: Memory in schizophrenia: what is impaired and what is preserved? Neuropsychologia 1993; 31:1225–1241Google Scholar

42. Colombo C, Abbruzzese M, Livian S, Scotti G, Locatelli M, Bonfanti A, Scarone S: Memory functions and temporal-limbic morphology in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 1993; 50:45–56Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Everett J, Laplante L, Thomas J: The selective attention deficit in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 1989; 177:735–738Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Frame CL, Oltmanns TF: Serial recall by schizophrenic and affective patients during and after psychotic episodes. J Abnorm Psychol 1982; 91:311–318Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Ganzevles PGJ, Haenen M-A: A preliminary study of externally and self-ordered task performance in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1995; 16:67–71Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR, Pliskin NH, Berman KF, Podd MH: Recall memory deficit in schizophrenia: a possible manifestation of prefrontal dysfunction. Schizophr Res 1989; 2:251–257Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Goldberg TE, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR: Course of schizophrenia: neuropsychological evidence for a static encephalopathy. Schizophr Bull 1993; 19:797–804Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Goldberg TE, Torrey EF, Gold JM, Ragland JD, Bigelow LB, Weinberger DR: Learning and memory in monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1993; 23:71–85Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Granholm E, Morris SK, Sarkin AJ, Asarnow RF, Jeste DV: Pupillary responses index overload of working memory resources in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol 1997; 106:458–467Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Gras-Vincendon A, Danion J-M, Grange D, Bilik M, Willard-Schroeder D, Sichel J-P, Singer L: Explicit memory, repetition priming and cognitive skill learning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1994; 13:117–126Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Hagger C, Buckley P, Kenny JT, Friedman L, Ubogy D, Meltzer HY: Improvement in cognitive functions and psychiatric symptoms in treatment-refractory schizophrenic patients receiving clozapine. Biol Psychiatry 1993; 34:702–712Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Harvey PD, Earle-Boyer EA, Wielgus MS, Levinson JC: Encoding, memory, and thought disorder in schizophrenia and mania. Schizophr Bull 1986; 12:252–261Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Harvey PD, Serper MR: Linguistic and cognitive failures in schizophrenia: a multivariate analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis 1990; 178:487–494Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Hoff AL, Riordan H, O’Donnell DW, Morris L, DeLisi LE: Neuropsychological functioning of first-episode schizophreniform patients. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:898–903Link, Google Scholar

55. Hutton SB, Puri BK, Duncan L-J, Robbins TW, Barnes TRE, Joyce EM: Executive function in first-episode schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1998; 28:463–473Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Kenny JT, Friedman L, Findling RL, Swales TP, Strauss ME, Jesberger JA, Schulz SC: Cognitive impairment in adolescents with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1613–1615Google Scholar

57. Kenny JT, Meltzer HY: Attention and higher cortical functions in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry 1991; 3:269–275Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Koh SD, Kayton L, Peterson RA: Affective encoding and consequent remembering in schizophrenic young adults. J Abnorm Psychol 1976; 85:156–166Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Kolb B, Whishaw IQ: Performance of schizophrenic patients on tests sensitive to left or to right frontal, temporal, or parietal function in neurological patients. J Nerv Ment Dis 1983; 171:435–443Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Kwapil TR, Chapman LJ, Chapman JP: Monaural and binaural story recall by schizophrenic subjects. J Abnorm Psychol 1992; 101:709–716Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Landrø NI, Ørbeck AL, Rund BR: Memory functioning in chronic and non-chronic schizophrenics, affectively disturbed patients and normal controls. Schizophr Res 1993; 10:85–92Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Lutz J, Marsh TK: The effect of a dual level word list on schizophrenic free recall. Schizophr Bull 1981; 7:509–515Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Nathaniel-James DA, Brown R, Ron MA: Memory impairment in schizophrenia: its relationship to executive function. Schizophr Res 1996; 21:85–96Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Park S, Holzman PS: Schizophrenics show spatial working memory deficits. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:975–982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65. Paulsen JS, Heaton RK, Sadek JR, Perry W, Delis DC, Braff D, Kuck J, Zisook S, Jeste D: The nature of learning and memory impairments in schizophrenia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1995; 1:88–99Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66. Radant AD, Claypoole K, Wingerson DK, Cowley DS, Roy-Byrne PP: Relationships between neuropsychological and oculomotor measures in schizophrenia patients and normal controls. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 42:797–805Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. Ragland JD, Censits DM, Gur RC, Glahn DC, Gallacher F, Gur RE: Assessing declarative memory in schizophrenia using Wisconsin Card Sorting Test stimuli: the Paired Associate Recognition Test. Psychiatry Res 1996; 60:135–145Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68. Randolph C, Gold JM, Kozora E, Cullum CM: Estimating memory function: disparity of Wechsler Scale—Revised and California Verbal Learning Test indices in clinical and normal samples. Clin Neuropsychol 1994; 8:99–108Crossref, Google Scholar

69. Russell PN, Beekhuis ME: Organization in memory: a comparison of psychotics and normals. J Abnorm Psychol 1976; 85:527–534Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70. Rizzo L, Danion J-M, Van der Linden M, Grange D: Patients with schizophrenia remember that an event has occurred, but not when. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168:427–431Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Salamé P, Danion J-M, Peretti S, Cuervo C: The state of functioning of working memory in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1998; 30:11–29Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

72. Saykin AJ, Shtasel DL, Gur RE, Kester DB, Mozley LH, Stafiniak P, Gur RC: Neuropsychological deficits in neuroleptic naive patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:124–131Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

73. Schwartz BL, Rosse RB, Deutsch SI: Limits of the processing view in accounting for dissociations among memory measures in a clinical population. Mem Cognit 1993; 21:63–72Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

74. Seidman LJ, Stone WS, Jones R, Harrison RH, Mirsky AF: Comparative effects of schizophrenia and temporal lobe epilepsy on memory. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1998; 4:342–352Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

75. Shedlack K, Lee G, Sakuma M, Xie S-H, Kushner M, Pepple J, Finer DL, Hoff AL, DeLisi LE: Language processing and memory in ill and well siblings from multiplex families affected with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1997; 25:43–52Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

76. Shoqueirat MA, Mayes AR: Spatiotemporal memory and rate of forgetting in acute schizophrenics. Psychol Med 1988; 18:843–853Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

77. Speed M, Toner BB, Shugar G, Di Gasbarro I: Thought disorder and verbal recall in acutely psychotic patients. J Clin Psychol 1991; 47:735–744Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

78. Stefánsson SB, Jónsdóttir TJ: Auditory event-related potentials, auditory digit span, and clinical symptoms in chronic schizophrenic men on neuroleptic medication. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40:19–27Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

79. Stirling JD, Hellewell JSE, Hewitt J: Verbal memory impairment in schizophrenia: no sparing of short-term recall. Schizophr Res 1997; 25:85–95Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

80. Stone M, Gabrieli JDE, Stebbins GT, Sullivan E: Working memory deficits in schizophrenia. Neuropsychology 1998; 12:278–288Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

81. Stratta P, Daneluzzo E, Prosperini P, Bustini M, Mattei P, Rossi A: Is Wisconsin Card Sorting Test performance related to “working memory” capacity? Schizophr Res 1997; 27:11–19Google Scholar

82. Sullivan EV, Shear PK, Zipursky RB, Sagar HJ, Pfefferbaum A: Patterns of content, contextual, and working memory impairments in schizophrenia and nonamnesic alcoholism. Neuropsychology 1997; 11:195–206Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

83. Traupmann KL: Encoding processes and memory for categorically related words by schizophrenic patients. J Abnorm Psychol 1980; 89:704–716Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

84. Traupmann KL, Anderson LT: Imagery and the short-term recall of words by schizophrenics. Psychol Record 1981; 31:47–56Crossref, Google Scholar

85. Hedges LV, Olkin I: Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. Orlando, Fla, Academic Press, 1985Google Scholar

86. Rosenthal R: Meta-Analytic Procedures for Social Research. London, Sage Publications, 1991Google Scholar

87. Shaddish WR, Haddock CK: Combining estimates of effect size, in The Handbook of Research Synthesis. Edited by Cooper H, Hedges V. New York, Sage Publications, 1994, pp 261–285Google Scholar

88. Schwarzer R: Meta-analysis programs. Behavior Res Methods, Instruments, and Computers 1988; 20:338Crossref, Google Scholar

89. Goldberg TE, Ragland D, Torrey EF, Bigelow LB, Gold JM, Weinberger DR: Neuropsychological assessment of monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47:1066–1072Google Scholar

90. Orwin RG: A fail-safe N for effect size in meta-analysis. J Educational Statistics 1983; 8:157–159Google Scholar

91. Egger M, Davey-Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C: Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315:629–634Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

92. Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK: Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology 1998; 12:426–445Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

93. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988Google Scholar

94. Burt DB, Zembar MJ, Niederehe G: Depression and memory impairment: a meta-analysis of the association, its pattern, and specificity. Psychol Bull 1995; 117:285–305Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

95. Squire LR: Memory and the hippocampus: a synthesis from findings with rats, monkeys and humans. Psychol Rev 1992; 99:192–231Google Scholar

96. Hijman R: Memory processes and memory systems: fractionation of human memory. Neurosci Res Commun 1996; 19:189–196Crossref, Google Scholar

97. Lawrie SM, Abukmeil SS: Brain abnormality in schizophrenia: a systematic and quantitative review of volumetric magnetic resonance studies. Br J Psychiatry 1998; 172:110–120Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

98. Wheeler MA, Stuss DT, Tulving E: Frontal lobe damage produces episodic memory impairment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1995; 1:525–536Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

99. Ungerleider LG: Functional brain imaging studies of cortical mechanisms for memory. Science 1995; 270:769–775Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

100. Liddle PF: Schizophrenic syndromes, cognitive performance and neurological dysfunction. Psychol Med 1987; 17:49–57Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

101. Liddle PF, Morris DL: Schizophrenic syndromes and frontal lobe performance. Br J Psychiatry 1991; 158:340–345Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

102. Frith CD: Schizophrenia, memory and anticholinergic drugs. J Abnorm Psychol 1984; 93:339–341Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

103. Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR: Effects of neuroleptic medication on the cognition of patients with schizophrenia: a review of recent studies. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 9):62–65Google Scholar

104. Mortimer AM: Cognitive function in schizophrenia: do neuroleptics make a difference? Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1997; 56:789–795Google Scholar

105. Green MF, Marshall BD Jr, Wirshing WC, Ames D, Marder SR, McGurk S, Kern RS, Mintz J: Does risperidone improve verbal working memory in treatment-resistant schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:799–804Google Scholar

106. Keefe RSE: The contribution of neuropsychology to psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:6–15Link, Google Scholar

107. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:321–330Google Scholar