Suicidal Behavior in Schizophrenia: Characteristics of Individuals Who Had and Had Not Attempted Suicide

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study compares demographic and clinical characteristics of 52 individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who had attempted suicide with those of 104 individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who had not made a suicide attempt. METHOD: Participants were interviewed with the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies. RESULTS: Most suicide attempts were of moderate to severe lethality, required medical attention, and involved significant suicidal intent. Individuals who had and had not attempted suicide did not differ with respect to demographic variables, duration of illness, rate of depression, or substance abuse. The two groups are affected differentially when depressed. CONCLUSIONS: Biopsychosocial assessments and interventions are essential for reducing the risk for suicidal behavior in individuals with schizophrenia.

Individuals with schizophrenia are at a high risk for suicidal behavior. The importance of determining risk factors for suicidal behavior in schizophrenia has been emphasized (1–3). Ten percent to 13% of individuals with schizophrenia commit suicide, and 20% to 40% make suicide attempts. The majority of those who commit suicide have made previous attempts. Existent studies have been based on retrospective chart review, were conducted before the use of DSM-III and current antipsychotic medications, and lacked standardized clinical assessments.

While some studies have suggested that specific demographic and clinical variables are associated with suicide attempts in schizophrenia, these associations are often inconsistent. Research reviews (1–3) suggest that men commit suicide more often than women, but they do not differ from women with respect to the rate of suicide attempts. The risk for suicidal behavior is high throughout the life span in those with schizophrenia, although most individuals attempt suicide in the first 10 years of illness. Risk is higher following acute psychotic episodes and during the first 6 months after hospitalization. Major depression and substance abuse may be related to suicide attempts in schizophrenia.

We studied individuals with schizophrenia who had and had not attempted suicide. The goals of this study were 1) to characterize a study group of individuals with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder who had attempted suicide and 2) to compare individuals with schizophrenia who had and had not attempted suicide with respect to demographic and clinical variables.

METHOD

One hundred fifty-six individuals with schizophrenia (72%, N=112) or schizoaffective disorder (28%, N=44) participated. The mean age was 37.61 years (SD=11.84); 60% were men, 43% were Caucasian, and 72% had never married. The mean duration of illness was 15.97 years (SD=10.52), with a mean age at onset of psychosis of 21.60 years (SD=7.69). Subjects were 75 voluntary research subjects recruited from the Schizophrenia Research Unit at New York State Psychiatric Institute, without regard for family history of psychiatric illness, or were 81 members of multiplex schizophrenia families recruited from the Diagnostic Center for Linkage Studies in Schizophrenia (4). All subjects provided written informed consent. Data regarding suicidal behavior and demographic and clinical characteristics in the Schizophrenia Research Unit and the Diagnostic Center for Linkage Studies in Schizophrenia studies were statistically compared and found to be comparable; thus, the two groups were combined.

The Diagnostic Interview of Genetic Studies, 2.0 (5), was administered to assess lifetime history of psychopathology and suicidal behavior. The Diagnostic Interview of Genetic Studies has demonstrated good diagnostic reliability in our group (5). Suicidal behavior was assessed by using the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies suicide section (derived from the Harkavy-Asnis Suicide Survey [6]). Over 90% of the suicide attempts were corroborated by medical records.

For the patients from the Diagnostic Center for Linkage Studies in Schizophrenia, best-estimate DSM-III-R diagnoses were generated by the National Institute of Mental Health Genetics Initiative (4); two diagnosticians (C.A.K. and D.M.) determined consensus diagnoses on the basis of the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies, the Family Interview for Genetic Studies (7), and medical records. For patients from the Schizophrenia Research Unit, DSM-III-R diagnoses based on the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies, medical record data, inpatient observational data, and clinical research ratings were determined by a consensus of the clinical and research team. Consensus diagnoses do not permit an assessment of reliability.

RESULTS

Thirty-three percent (N=52) of this study group reported at least one suicide attempt; 60% (N=31) of those who had attempted suicide reported multiple attempts. The rates of attempts for those with schizophrenia and those with schizoaffective disorder were not significantly different (39%, N=17, versus 31%, N=35) (χ2=0.77, df=1, p=0.38). There also was no significant difference between those who had and had not attempted suicide with regard to the rate of schizoaffective disorder (33%, N=17, versus 26%, N=27) (χ2=0.78, df=1, p=0.38). Therefore, individuals with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder were combined.

Fifty-two percent (N=27) of those who had attempted suicide made attempts of moderate to extreme lethality, and 36 (76% of the 47 patients for whom these data were available) reported strong suicidal intent. For the most severe attempts, suicidal behavior included overdosing (42%), slitting one’s wrists (16%), jumping (8%), hanging (6%), and other methods (i.e., running into highway traffic or stabbing oneself) (18%). Fifty-seven percent of those who had attempted suicide were admitted to inpatient medical units, and 11% were treated in emergency rooms after their attempts.

The 88 reasons given for the attempts included depression (N=28), loss of a significant other (i.e., spouse, boyfriend/girlfriend) (N=14), being bothered by psychotic symptoms (N=11), response to a stressful life event (N=10), response to command auditory hallucinations (N=4), “to escape” (N=4), because he or she was being physically abused (N=3), substance abuse (N=2), for attention (N=2), and for unknown reasons (N=10).

Given the large number of comparisons conducted, the Bonferroni correction was calculated for the six demographic comparisons, and the significance level was set at p<0.008. Those who had and had not attempted suicide were comparable with respect to age (had attempted suicide: mean=37.17 years, SD=10.41; had not: mean=37.82 years, SD=12.54) (t=0.04, df=120, p=0.73); sex (62% were men versus 58% were men) (χ2=0.21, df=1, p=0.64); race (50% Caucasian, 21% African American, 17% Latino, 12% other versus 39% Caucasian, 27% African American, 22% Latino, 12% other) (χ2=2.60, df=3, p=0.46); education (mean=12.06 years, SD=2.96, versus mean=12.5 years, SD=2.77) (t=0.88, df=109, p=0.37); marital status (never married: 73% versus 72%) (χ2=1.13, df=4, p=0.89), or living arrangement (live with family/friends: 63% versus 61%) (χ2=6.34, df=7, p=0.50).

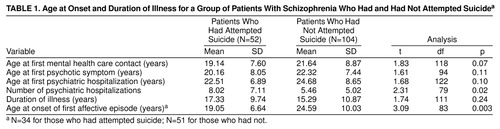

The Bonferroni correction was used for the 14 analyses assessing clinical characteristics, and the significance level for these analyses was set at p<0.004 (Table 1). The groups were comparable with respect to age at onset of psychosis, duration of illness, age at first mental health care contact, age at first psychiatric hospitalization, and number of psychiatric hospitalizations.

More than 80% (N=43) of those who had attempted suicide reported that their first attempt occurred after the onset of psychosis (mean=3.86 years after onset, SD=8.01) (paired t=3.41, df=49, p=0.001) and after their first hospitalization (mean=4.57 years after first hospitalization, SD=8.62) (paired t=3.68, df=46, p=0.001).

The groups did not differ with respect to history of 1 week of significant depressed mood (had attempted suicide: 60%, N=31; had not: 55%, N=57) (χ2=0.33, df=1, p=0.56) or history of a major depressive episode (58%, N=30, versus 43%, N=45) (χ2=2.89, df=1, p=0.09). Suicidal ideation during depression occurred twice as often for those who had attempted suicide (80%, N=24) as for those who had not (42%, N=19) (χ2=9.93, df=1, p=0.002), and 57% (N=17) of those who had attempted suicide who had a history of depression reported having made a suicide attempt during a major depressive episode. Those who had attempted suicide reported that their first affective episode occurred significantly earlier than that of those who had not. The groups were comparable with respect to history of a manic episode (27%, N=14, versus 23%, N=24) (χ2=0.09, df=1, p=0.77). The groups did not differ with respect to history of alcohol abuse/dependence (31%, N=16, versus 21%, N=22) (χ2=1.24, df=1, p=0.27) or drug abuse/dependence (27%, N=14, versus 24%, N=25) (χ2=0.34, df=1, p=0.56).

DISCUSSION

The rate of suicide attempts in this group of individuals with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder was high and comparable to that found in other studies (1–3). In contrast to groups without schizophrenia, the suicide attempts were serious, typically requiring medical attention. Intent was strong, and the majority of those who had attempted suicide made multiple attempts. Compared with other groups, the rate of suicide attempts by overdose was relatively low (only 42%, N=22), and the rate of more lethal methods was higher. Consistent with other research, those with schizophrenia who had and had not attempted suicide did not differ with respect to demographic characteristics (1–3).

This is the first study to document reasons for having made a suicide attempt among individuals with schizophrenia. The most frequent reason was that the person was depressed. We do not know how many individuals in this group actually met the criteria for major depression at the time of the attempt. The next most frequent reason was the loss of a spouse or boyfriend/girlfriend. While most individuals in this study group were not married, they had been involved in romantic relationships. These types of relationships have not been fully considered in previously published reports. As documented by others (1–3), the rate of suicide attempts in response to command hallucinations was low, although 11 attempts were made because the presence of psychotic symptoms was bothersome. This stresses the importance of treating psychosis and monitoring symptoms throughout the course of illness. Few patients reported that they had made a suicide attempt because of problems with substance abuse. Ten attempts were made in response to stressful life events, emphasizing the importance of attending to psychosocial functioning.

More than 80% (N=43) of first suicide attempts occurred after the onset of psychosis and within the first 5 years of illness, suggesting that the risk for suicidal behavior is higher after the onset of schizophrenia. Since the suicidal behavior did not occur at the actual time of onset of psychosis or at the time of the first mental health care contact, it is unlikely that suicidal behavior was the reason for the first mental health care contact.

No clinical syndromes differentiated the patients who had from those who had not attempted suicide; thus, their mere presence is not predictive. The findings are consistent with, but not necessarily predictive of, a stress-diathesis model such that clinical syndromes may trigger suicidal behavior in those already at risk. For example, while a history of depression did not differentiate the groups, depression increased the risk for suicidal behavior for those who had attempted suicide. The earlier onset of affective illness in those who had attempted suicide also highlights the importance of early recognition and treatment of affective illness in schizophrenia.

Lifetime psychopathology and suicidal behavior were assessed by using a standardized interview. While the study group size is relatively large, it is not large enough to adequately detect group differences when subgroups of individuals are considered or to apply sophisticated multivariate analyses. A strength of the study group is that individuals were not necessarily in an acute state of illness when they participated, providing a more community-based, more representative study group. However, all participants had to agree to participate in the research, thereby limiting the generalizability of the results. Finally, suicidal behavior was remote relative to the time of the assessment, so that this study does not examine the relationship between suicidal behavior and specific risk factors more proximal to a suicide attempt.

This study supports the need for prospective evaluation of suicidal behavior and its associated risk factors; it also supports the need for ongoing biopsychosocial assessments and interventions targeting psychotic and depressive symptoms with pharmacological agents and psychosocial interventions.

Received Jan. 26, 1998; revision received Jan. 21, 1999; accepted Feb. 8, 1999. From the Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York. Address reprint requests to Dr. Harkavy-Friedman, 1051 Riverside Dr., Unit 6, New York, NY 10032. Funded in part by the American Foundation for the Prevention of Suicide and NIMH grants MH-46289 and MH-50727. The authors thank Vincent Vinceguerra, Martin McElhiney, Salome Looser-Ott, Habib Ahsan, Syeeda Parveen, and the staff of the Schizophrenia Research Unit at New York State Psychiatric Institute.

|

1. Drake RE, Gates C, Cotton PG, Whitaker A: Suicide among schizophrenics: who is at risk? J Nerv Ment Dis 1984; 172:613–618Google Scholar

2. Caldwell BC, Gottesman II: Schizophrenics kill themselves too: a review of the risk factors for suicide. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16:571–589Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Harkavy-Friedman JM, Nelson E: Management of the suicidal patient with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1997; 20:625–640Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Cloninger CR: Turning point in the design of linkage studies of schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet 1997; 54:83–92Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Nurnberger JI Jr, Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, York-Cooler C, Simpson SG, Harkavy-Friedman JM, Severe JB, Malaspina D, Reich T, NIMH Genetics Initiative: Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies: rationale, unique features, and training. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:849–859Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Harkavy-Friedman JM, Asnis GM: Assessment of suicidal behavior: a new instrument. Psychiatr Annals 1989; 19:382–387Crossref, Google Scholar

7. NIMH Molecular Genetics Initiative: Family Interview for Genetic Studies. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1992Google Scholar