Treatment of Schizoaffective Disorder and Schizophrenia With Mood Symptoms

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Patients with concurrent schizophrenic and mood symptoms are often treated with antipsychotics plus antidepressant or thymoleptic drugs. The authors review the literature on treatment of two overlapping groups of patients: those with schizoaffective disorder and those with schizophrenia and concurrent mood symptoms. METHOD: MEDLINE searches (from 1976 onward) were undertaken to identify treatment studies of both groups, and references in these reports were checked. Selection of studies for review was based on the use of specified diagnostic criteria and of parallel-group, double-blind design (or, where few such studies addressed a particular issue, large open studies). A total of 18 treatment studies of schizoaffective disorder and 15 of schizophrenia with mood symptoms were selected for review. RESULTS: For acute exacerbations of schizoaffective disorder or of schizophrenia with mood symptoms, antipsychotics appeared to be as effective as combination treatments, and there was some evidence for superior efficacy of atypical antipsychotics. There was evidence supporting adjunctive antidepressant treatment for schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients who develop a major depressive syndrome after remission of acute psychosis, but there were mixed results for treatment of subsyndromal depression. There was little evidence to support adjunctive lithium for depressive symptoms and no evidence concerning its use for manic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. CONCLUSIONS: Empirical data suggest that both groups of patients are best treated by optimizing antipsychotic treatment and that atypical antipsychotics may prove to be most effective. Adjunctive antidepressants may be useful for patients with major depression who are not acutely ill. Careful longitudinal assessment is required to ensure identification of primary mood disorders.

In clinical settings, many psychotic patients receive schizoaffective diagnoses and are treated with combinations of antipsychotic, thymoleptic, and/or antidepressant drugs. For example, 19% of 6,000 surveyed inpatients in New York State psychiatric hospitals were diagnosed as schizoaffective, and most of these were being treated with such drug combinations (W. Tucker, personal communication, March 1997). However, empirical data provide relatively little guidance in selecting treatment for these patients. One problem for both clinicians and researchers is that current diagnostic categories for these patients are neither highly reliable nor predictive of response to treatment. In this article we briefly discuss relevant diagnostic issues and then review available treatment studies, with an emphasis on controlled trials.

DIAGNOSIS OF PATIENTS WITH CONCURRENT SCHIZOPHRENIC AND MOOD SYMPTOMS

Kraepelin (1) divided functional psychoses into dementia praecox and manic-depressive psychosis, but his rich clinical examples included many patients with mixed features. Kasanin (2) proposed the term “schizoaffective psychosis” for patients with schizophrenic and affective symptoms, but he described an acute, confusional psychosis that differs from current definitions. A number of researchers developed criteria for schizoaffective disorders (3–8), generally finding a long-term outcome that was better than in schizophrenia but worse than in affective psychoses (5). The Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) (9) were the first to achieve widespread acceptance among researchers. Schizoaffective disorder was defined as the acute co-occurrence of a full mood syndrome (depression and/or mania) and one of a set of “core schizophrenic” symptoms, such as bizarre delusions, first-rank symptoms, or nearly continuous hallucinations.

The RDC were intended to facilitate study of diverse diagnostic definitions. Distinctions were made between schizoaffective depressed versus manic and chronic versus nonchronic subtypes. Another critical distinction was between the mainly schizophrenic subtype, requiring persistence of psychosis for more than a week (or poor premorbid functioning), and the mainly affective subtype, with no persistence of psychosis for more than a week (and good premorbid functioning). This distinction was based on clinical evidence that persistence of psychosis predicted poor response to mood disorder treatments (8). In a number of well-designed family studies, relatives of patients with schizoaffective disorder, affective subtype, and of patients with mood disorders were found to have increased rates of mood disorders but not schizophrenia in comparison with control families. There was an increased prevalence of schizophrenia in the relatives of patients with schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenic subtype, and of patients with schizophrenia (10, 11), although one study showed no difference in the risk of schizophrenia in relatives of patients with schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenic subtype, compared with those of patients with the affective subtype (12). Patients with the affective subtype also appeared to show greater response to mood disorder treatments (see below). These data tended to favor considering schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenic subtype, to be closely related to schizophrenia, and schizoaffective disorder, affective subtype, to be closely related to mood disorders.

Therefore, in DSM-III-R (and subsequently DSM-IV), patients with RDC schizoaffective disorder, affective subtype, were defined as having mood psychoses with non-mood-congruent features. Schizoaffective disorder was defined as a modified version of RDC schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenic subtype: co-occurrence of schizophrenic and mood syndromes, with persistence of psychosis for 2 weeks after remission of prominent mood symptoms. However, one issue had never been addressed by the RDC or RDC-based research: what diagnosis should be given when there are periods meeting criteria for schizoaffective disorder and others resembling schizophrenia? In the absence of relevant research data, a rather subjective criterion was developed; schizophrenia was to be diagnosed if mood syndromes were not present for a substantial part of the psychotic illness.

Despite these efforts to clarify schizoaffective disorder as a clinical diagnosis, it has proven difficult to diagnose the disorder reliably. In the initial study of the RDC with the use of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (13), good interrater reliability (kappa=0.73–0.86) was demonstrated for schizoaffective disorder when schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenic subtype, and schizoaffective disorder, affective subtype, were combined into a single category, but this study has limited relevance to current criteria, since the RDC do not require making a judgment about the lifetime duration of mood syndromes in relation to schizophrenic symptoms, and the reliability of judging the persistence of schizophrenic symptoms within a single episode (affective subtype versus schizophrenic subtype) was also not determined. The major test-retest reliability study of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (14) found moderate reliability for schizoaffective disorder (kappa=0.63), similar to that for schizophrenia (kappa=0.65). However, the base rate for schizoaffective disorder was only 6%, and only two of five sites had enough patients with schizoaffective disorder to calculate site-specific reliability (kappa=0.43 at one site, and kappa=0.76 at the other). In the most extensive study to date (15), patients were interviewed by two different research clinicians no more than 3 weeks apart after the clinicians had had extensive training with the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies with the use of DSM-III-R criteria. Interrater reliability for schizoaffective disorder was poor (kappa=0.37), and the most frequent disagreement was about schizoaffective disorder versus schizophrenia, rather than schizoaffective disorder versus mood disorder.

Schizoaffective disorder is also sometimes defined quite differently across studies. There are family study investigators who assign a schizoaffective disorder diagnosis if a single psychotic exacerbation has included a full mood syndrome (“once schizoaffective disorder, always schizoaffective disorder”), or only if all psychotic exacerbations have included a full mood syndrome (“once schizophrenia, always schizophrenia”), or on the basis of judgments of a preponderance of mixed episodes (e.g., the study by the National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH] Genetics Initiative [15] adopted an additional criterion for schizoaffective disorder: that mood disorder be present for 30% of the periods of psychosis, including neuroleptic treatment periods).

In our experience, diagnostic judgments are often complicated by the difficulty of obtaining the information needed to apply these imprecise diagnostic criteria. Patients tend to overstate past depressive symptoms and understate past psychosis, as demonstrated by 2-year follow-up interviews in the NIMH Collaborative Study of Depression (J. Endicott, personal communication, May 1998). Family members seldom ask patients direct questions about psychosis during periods of relative remission, and standards of documentation of specific symptoms are generally low in both inpatient and outpatient settings. The assessment of current and past mood symptoms can also be confounded by uncertainty about the effects of negative symptoms of schizophrenia, neuroleptic treatment (such as akinesia and akathisia), substance abuse, stressful life events, and demoralization. In clinical practice, schizoaffective disorder diagnoses are probably even less consistent than in research studies. Many clinicians fail to assess the relative persistence of psychotic and mood symptoms between acute episodes, and others expand schizoaffective disorder to include chronic psychosis with a few prominent mood symptoms, as well as mood disorders with a severely psychotic acute presentation.

The relationship between schizophrenia and depressive symptoms is particularly problematic. In a careful follow-up study, Martin et al. (16) found that up to 60% of patients with stable, long-term diagnoses of schizophrenia reported an episode of major depression at some point. Others have estimated that about 25% of patients with schizophrenia may experience depression (17, 18). Since the DSM-III-R criteria for schizoaffective disorder were adopted, two family studies (12, 19) have also reported an increased risk of major depression (but not mania) in relatives of schizophrenic patients.

In the light of these considerations, the clinician should bear in mind that the research literature on treatment of schizoaffective disorder can only be used as a guide if a given study’s approach to diagnosis or assessment is carefully considered, and that the research evidence is an imperfect guide given the poor reliability of schizoaffective disorder diagnoses.

THE CLINICAL PROBLEM: HOW TO TREAT A SPECTRUM OF MIXED SYNDROMES

The clinician is therefore faced with a spectrum of patients with mixtures of schizophrenic and mood symptoms and syndromes. At one extreme of this spectrum is the patient whose early course seems most consistent with a psychotic mood disorder, who then develops more persistent psychotic symptoms suggesting schizoaffective disorder, but who has some concurrent mood symptoms (such as excited mood or subjective depression) that suggest a chronic mood disorder with psychosis. At the other extreme is the patient with very chronic features of schizophrenia, who also has symptoms that suggest a mood “component” although not a full mood syndrome. In between are patients with varying degrees of recurrence and persistence of mood symptoms or syndromes and of schizophrenic symptoms. The research literature summarized above provides essentially one distinction that can be assessed reliably and that is predictive of response to treatment: there are patients with mood syndromes and psychosis that never persists after remission of the mood symptoms (i.e., primary mood disorders with psychosis) and patients with psychosis that is observed for weeks or longer in the absence of mood syndromes (schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder). The distinction between schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder is apparently more difficult to assess reliably, and many clinical issues regarding patients with mixed psychotic and mood disorders have received little study.

Clinical practice with these patients appears to be dominated by anecdotal experience and by simplistic analogies. For example, if a chronic schizophrenic patient has expansive behavior and grandiose delusions, lithium or anticonvulsant drugs are often added to a neuroleptic regimen because of the assumption that this will help a manic component. While anecdotal experience cannot be ignored in the absence of good data from controlled studies or when the patient fails to respond to proven treatments, it is important to give first consideration to available controlled studies. We review here the available data on treatment of two types of patients: those diagnosed as having schizoaffective disorder (RDC schizoaffective disorder, mainly schizophrenic subtype; DSM-III-R schizoaffective disorder; or the equivalent) and those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and concurrent mood symptoms (with depressive symptoms receiving the most study). We focus on controlled, parallel-group trials but also review retrospective data based on large samples and uncontrolled data relevant to issues that have not been addressed by controlled trials.

METHOD

MEDLINE searches were conducted for papers published from 1976 onward on treatment of schizoaffective disorders and of schizophrenia with depressive or manic symptoms. References from relevant papers were cross-checked to develop a comprehensive list. Studies were selected for review if they met two criteria: 1) diagnoses were defined by acceptable criteria (RDC, DSM-III-R, or comparable criteria for schizoaffective disorder) and 2) two or more treatment conditions were compared in a double-blind design, or if few controlled studies were available, open studies with large samples were considered. Studies were then divided into two groups for presentation and discussion: studies of schizoaffective disorder and studies of mood symptoms in subjects with diagnoses of schizophrenia.

RESULTS

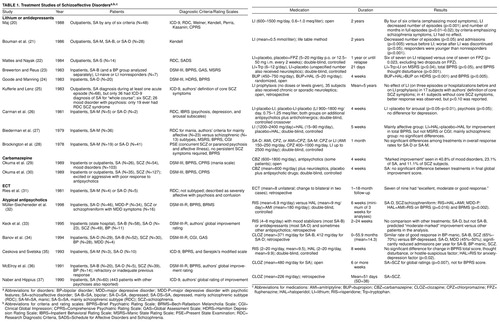

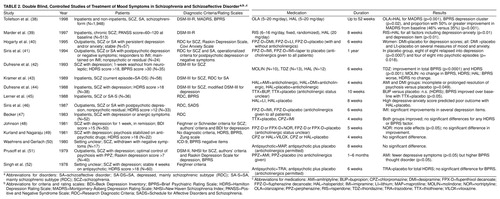

Table 1 summarizes data from selected studies of pharmacological treatment of schizoaffective disorders. Table 2.summarizes data from studies of treatment of mood symptoms in schizophrenia.

Treatment of Schizoaffective Disorders

Lithium for schizoaffective disorder, manic type

Three double-blind, parallel-group studies examined the efficacy of lithium in schizoaffective mania. Brockington et al. (28) studied 19 patients who met their criteria for schizophrenia or paranoid psychosis and for mania and found that chlorpromazine plus placebo was as effective as chlorpromazine plus lithium. Biederman et al. (27) studied 36 patients with RDC schizoaffective disorder, manic type, and found that haloperidol plus lithium was superior to haloperidol plus placebo in the patients with schizoaffective disorder, affective subtype, but not in the patients with schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenic subtype (i.e., lithium did not benefit patients who would be considered to have schizoaffective disorder by DSM-III-R or DSM-IV criteria). Mattes and Nayak (22) randomly assigned 14 patients with RDC schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenic subtype (manic type), who had been stable on fluphenazine, to continue this treatment along with placebo lithium tablets or to receive lithium and placebo fluphenazine for up to 1 year or until relapse. Fluphenazine was statistically superior: only patients who switched to lithium relapsed. One other controlled study is difficult to interpret; Carman et al. (26) studied just seven RDC schizoaffective disorder patients (five manic and two depressed), giving lithium or placebo (added to previous neuroleptic treatment) in a crossover design, and reported improvement in two of a large number of rating scale scores. There have been no controlled studies of lithium in samples defined by modern criteria for schizoaffective disorder, depressed type, and no large uncontrolled studies of this specific group.

Antidepressants for schizoaffective disorder, depressed type

In the investigation cited previously (28), Brockington et al. studied 41 patients who met their criteria for schizophrenia or paranoid psychosis and for depression and found that chlorpromazine plus placebo was as effective as chlorpromazine plus amitriptyline or amitriptyline alone. Note also the study by Kramer et al. (43), discussed below and summarized in Table 2., in which subjects were diagnosed as having schizophrenia with concurrent depression but received current-episode RDC diagnoses of schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenic subtype (depressed type), and in whom a neuroleptic alone was more effective than a neuroleptic with an antidepressant.

Atypical antipsychotics

Three open or retrospective studies of relatively large groups have examined the effect of clozapine on schizoaffective disorders. Banov et al. (34) examined 52 patients with DSM-III-R schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type; 29 patients with schizoaffective disorder, depressed type; and 30 patients with schizophrenia, all of whom were treated with clozapine for an average of 18.7 months. They found that patients with schizoaffective disorder improved more than patients with schizophrenia, and patients with schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type, improved more than patients with schizoaffective disorder, depressed type. Naber and Hippius (37) retrospectively analyzed data on 60 patients who were diagnosed according to ICD-9 (which, however, is not comparable to subsequent diagnostic systems) and treated acutely (mean=4.3 weeks) with clozapine; patients with schizoaffective disorder improved more than patients with schizophrenia. McElroy et al. (36) openly studied 25 patients with treatment-refractory disorders and found more improvement in patients with schizoaffective disorder than in patients with schizophrenia who had been taking clozapine for at least 6 weeks. A fourth study (33) retrospectively analyzed the outcomes of 81 patients with DSM-III-R schizoaffective disorder treated with risperidone for up to 24 weeks; the authors found that those with the depressed type improved more than those with the bipolar type. Ceskova and Svetska (35) studied haloperidol versus risperidone in an 8-week double-blind trial in 13 patients with schizoaffective disorder diagnosed according to ICD-9 and found the two drugs to be comparable. However, in the only prospective, double-blind, controlled study to date that specifically considered patients with schizoaffective disorder, Müller-Siecheneder et al. (32) found no advantage of risperidone over haloperidol plus amitriptyline in 46 patients with schizoaffective disorder, depressed type, while the latter combination was more effective than risperidone in 34 subjects with major depression with psychotic features. Taken together with the reports (discussed below) of positive effects of atypical antipsychotics on mood symptoms in schizophrenic patients, these studies suggest that these drugs could be more effective than typical neuroleptics for schizoaffective disorders, but results are inconsistent and additional controlled studies are needed.

Anticonvulsants

Okuma et al. (30) treated 35 patients with schizoaffective disorder for 4 weeks and found similar outcomes in those treated with neuroleptics plus carbamazepine and those treated with neuroleptics plus placebo (although DSM-III criteria were used, which do not specify criteria for schizoaffective disorder). For sodium valproate, the four open studies reported to date (53–56) were too small to merit inclusion in Table 1. Study group sizes were five to 14 patients (a total of 25), diagnoses were according to DSM-III criteria in three studies and unknown criteria in another (53), designs were open and usually retrospective, and largely descriptive data (global ratings of improvement) were reported, with no comparison treatments within the schizoaffective disorder group. It is unclear whether these data are relevant to treatment decisions about patients with schizoaffective disorder diagnosed according to current DSM-IV criteria.

Treatment of Schizophrenia With Depressive Symptoms

Neuroleptics

Neuroleptics have been shown to produce improvement in depressive symptoms in patients with exacerbations of schizophrenia or schizoaffective depression (42–44, 47, 57).

Atypical antipsychotics

Tollefson et al. (38) reported data from a double-blind, controlled, multicenter trial of treatment of exacerbations of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder with olanzapine (N=1,312) versus haloperidol (N=636) and found significantly greater improvement in depressive symptoms with olanzapine. Similarly, Marder et al. (39) reported that in 513 chronic schizophrenic subjects in two multicenter inpatient trials, risperidone was more effective than haloperidol in improving all symptom factors, including depression-anxiety. In a study not included in Table 2., Meltzer and Okayli (58) reported that patients with neuroleptic-resistant illness who had a history of suicidal ideation experienced a significant decrease in suicidal and depressive ideation during open treatment with clozapine.

Antidepressants

We found no controlled studies demonstrating an advantage of combinations of antidepressants and neuroleptics over neuroleptics alone in acute schizophrenic or schizoaffective psychosis. Most studies showed no difference between these two treatments, but Kramer et al. (43) found that haloperidol plus placebo produced greater improvement in psychotic symptoms than haloperidol plus either amitriptyline or desipramine in 58 patients with a history of DSM-III-defined schizophrenia and a current episode meeting criteria for RDC schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenic subtype, depressed type. Results of outpatient studies have been more mixed, with several demonstrating that addition of antidepressants to a neuroleptic regimen improved depressive symptoms (40, 51, 52) or depressive syndromes (41, 46) compared with addition of placebo. Prusoff et al. (51) reported worsening of formal thought disorder with antidepressants. Hogarty et al. (40) reported improvement in female but not male patients. Several studies showed no advantage to addition of antidepressants for depressive symptoms (47–49).

Lithium

There is one report of greater overall improvement (total score on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale [BPRS]) in patients with RDC-defined schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and high depression ratings who were given haloperidol plus lithium than in those given haloperidol plus placebo (45). There were only nine patients in each group (lithium versus placebo and high versus low baseline BPRS depression-anxiety rating).

Treatment of Schizophrenia With Manic Symptoms

We found no controlled studies of adjunctive treatments for schizophrenic patients with concurrent manic symptoms (other than those cited earlier of patients with schizoaffective disorder, manic type, who by definition have a full manic syndrome). Hogarty et al. (40) reported a positive effect of adjunctive lithium (versus adjunctive placebo) in schizophrenic outpatients with “anxiety,” which, as defined in that study, included some features that might be described as hypomanic by some observers.

DISCUSSION

On the basis of this review, we offer the following conclusions, which should be considered highly tentative given the dearth of controlled data, particularly regarding the newer antipsychotics, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers.

1. The diagnostic distinction most predictive of response to pharmacological treatment, according to available controlled studies, is between mood disorders with psychotic features and disorders in which psychosis persists in the absence of mood syndromes (schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder). Thus, the evaluation of patients with concurrent psychotic and mood symptoms should include a thorough review of the entire course of illness to determine whether a primary mood disorder with psychotic features is present, and if so, vigorous treatment efforts will be based on the literature on mood disorders rather than on the studies reported here. By contrast, there is little evidence that the distinction between DSM-IV schizophrenic and schizoaffective disorders is substantially predictive of response to available treatments, and indeed the reliability of this distinction has not been clearly established.

2. For patients with acute exacerbations of schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia with depressive symptoms, controlled data suggest that antipsychotic drugs are the best available treatments and that adjunctive antidepressants are of no benefit or may even have a negative effect. Atypical antipsychotics may prove advantageous. Several large open studies (but not the one controlled study to date) suggested superiority of these agents for schizoaffective patients, two controlled studies demonstrated an advantage in alleviating depressive symptoms in schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients, and one open study reported reduced suicidality in schizophrenic patients treated with clozapine. Thus, the data are most supportive of optimization of neuroleptic treatment, including minimization of extrapyramidal symptoms and trials of atypical antipsychotics, rather than routine use of adjunctive antidepressants. Clinicians should recognize that while antidepressants may be helpful to individual patients, their use is not well supported by controlled studies. We suggest that such trials should be discontinued if there is no significant improvement. And when improvement is observed, there should be an attempt to monitor the patient both on and off the adjunctive treatment to determine whether it is predictably associated with improvement or whether the initial improvement might be better explained by the extra time on the original antipsychotic treatment regimen, variation in the course of illness, variation in substance abuse, or other factors.

3. There is substantial evidence, however, to support trials of adjunctive antidepressants in schizophrenic and schizoaffective outpatients who have new or continued full major depressive syndromes after psychosis has stabilized. We again suggest that antidepressants be discontinued if psychosis worsens or if there is no improvement after adequate trials, and that patients who do improve be observed while on and off antidepressants to determine whether their continued use is warranted.

4. There is mixed evidence concerning addition of antidepressants for depressive symptoms (as opposed to syndromes) in schizophrenic outpatients. We tentatively conclude that such trials are not consistently beneficial and that there may be some risks (worsening of psychosis has sometimes been observed). We suggest that clinicians give careful consideration to other possible interventions (optimization of neuroleptic treatment, use of atypical antipsychotics, intervention for psychosocial stressors, assessment and reduction of substance abuse), avoid routine use of antidepressants for complaints of depression, and evaluate the outcome of such trials by observing patients when they are both on and off antidepressants.

5. Adjunctive use of lithium for depressive symptoms in schizophrenia has not received sufficient study to draw conclusions. There are no studies of addition of lithium for specific mania-like symptoms. There is currently no empirical basis for the widespread long-term administration of lithium and other thymoleptics to patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. We urge greater skepticism and caution about the use of these agents in these patients pending further research.

6. There are few controlled studies of the newer thymoleptic agents such as sodium valproate or of the newer antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients.

We note that the American Psychiatric Association’s recent Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia(59) differs substantially from our conclusions and recommendations in one area. The Guideline concludes that there is some support for use of lithium in both schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. Two studies of schizophrenic patients are cited. Small et al. (60) studied 14 schizophrenic and eight schizoaffective patients in a balanced crossover design (two 4-week periods on adjunctive lithium and two on placebo); there were 15 completers, and of multiple statistical comparisons, there was one with an uncorrected p value of <0.05; i.e., this was a study with negative results. Growe et al. (61) studied six schizophrenic and two schizoaffective patients in a similar crossover design and observed an advantage of lithium at p<0.01 for one of eight rating scales; i.e., this was also a study with negative results and too few subjects to support strong conclusions. Furthermore, there are reasons for the dearth of controlled data in the years since those studies were published: 18 years: many clinical research investigators have observed multiple patients with schizophrenia who have not responded to adjunctive lithium, so there is limited enthusiasm for initiating new large studies to resolve the issue.

The Guideline refers to four studies as evidence of the efficacy of lithium in schizoaffective disorders. Johnson (62) and Prien et al. (63) used older diagnostic criteria, which would have included many patients with primary mood disorder. Carman et al. (26) studied just seven patients, and Biederman et al. (27) observed improvement in patients with schizoaffective disorder, mainly affective type (i.e., mood disorder) rather than schizoaffective disorder, mainly schizophrenic type, as defined by the RDC. Evidence from controlled studies, as discussed earlier, fails to support the use of lithium in these patients.

The most recent review of pharmacological treatment of schizoaffective disorder (64) discussed some of the studies reviewed here and concluded similarly that there were no controlled data to support combination neuroleptic-thymoleptic treatment. The authors also took a more positive view toward the uncontrolled data favoring such combinations, whereas we have suggested that there are few data relevant to patients who would be considered schizoaffective by current DSM-IV criteria (rather than the RDC). They suggested that uncontrolled data favored the use of atypical neuroleptics, and this conclusion has generally been supported by subsequent controlled studies of mood symptoms associated with schizophrenia, but specifically for schizoaffective disorder, as discussed above.

In conclusion, controlled data suggest that typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs are most effective for the acute and maintenance treatment of patients with schizoaffective disorders and of schizophrenic patients with mood symptoms. Optimization of antipsychotic treatment is thus more likely to be effective than the routine use of adjunctive antidepressants or mood stabilizers. The one exception is that the use of antidepressants is well supported in schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients who present with a full depressive syndrome after stabilization of psychosis. There are few if any data to support the use of antidepressants or thymoleptics for subsyndromal depressive symptoms or for depression during acute schizophrenic or schizoaffective exacerbation.

Why, then, are these agents so widely prescribed for schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients? The major factor is probably that suboptimal response to antipsychotic drugs remains common, while depressive and manic symptoms are common in patients whose long-term course otherwise suggests schizophrenia, so antidepressants and thymoleptics often offer the physician the only justifiable option for improving outcome. Also, thymoleptics and the newer antidepressants have favorable side effect profiles, so their risks usually seem minimal compared with the possible benefits of reducing distressing mood symptoms, and it may seem easier to add one of these drugs than to risk substituting another antipsychotic drug for one that has been at least partially effective. We suggest, however, that there is little controlled evidence supporting this practice (except for antidepressants for postpsychotic major depressive syndrome). Until more controlled studies are available, the most rational approach would be to make substantial efforts to optimize antipsychotic drug treatment (including trials of atypical antipsychotics) before adding antidepressants or thymoleptics. Trials of the latter agents might best be viewed as humanitarian “single-subject experiments,” so the adjunctive drug should be discontinued if there is no response, and an apparent response can best be evaluated by stopping and restarting the adjunctive agent one or more times while monitoring relevant target symptoms.

Received June 9, 1998; revision received Dec. 18, 1998; accepted Dec. 30, 1998. From the Department of Psychiatry, MCP Hahnemann School of Medicine, Allegheny University of the Health Sciences. Address reprint requests to Dr. Levinson, AUH-EPPI, 3200 Henry Ave., Room 206, Philadelphia, PA 19129; [email protected] (e-mail)

|

|

1. Kraepelin E: Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia (1919). Translated by Barclay RM; edited by Robertson GM. New York, Robert E Krieger, 1971Google Scholar

2. Kasanin J: The acute schizoaffective psychoses. Am J Psychiatry 1933; 90:97–126Link, Google Scholar

3. Welner A, Croughan JL, Robins E: The group of schizoaffective and related psychoses—critique, record, follow-up, and family studies, I: a persistent enigma. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 31:628–631Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Abrams R, Taylor MA: Mania and schizo-affective disorder, manic type: a comparison. Am J Psychiatry 1976; 133:1445–1447Google Scholar

5. Tsuang MT, Dempsey GM: Long-term outcome of major psychoses, II: schizoaffective disorder compared with schizophrenia, affective disorders, and a surgical control group. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:1302–1304Google Scholar

6. Rosenthal NE, Rosenthal LN, Stallone F, Dunner DL, Fieve RR: Toward the validation of RDC schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980; 37:804–810Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Brockington IF, Wainwright S, Kendell RE: Manic patients with schizophrenic or paranoid symptoms. Psychol Med 1980; 10:73–83Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Himmelhoch JA, Fuchs CZ, May SJ, Symons BJ, Neil JF: When a schizoaffective diagnosis has meaning. J Nerv Ment Dis 1981; 169:277–282Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) for a Selected Group of Functional Disorders, 3rd ed, updated. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1981Google Scholar

10. Baron M, Gruen R, Asnis L, Kane J: Schizoaffective illness, schizophrenia and affective disorders: morbidity risk and genetic transmission. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1982; 65:253–262Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Kendler KS, Gruenberg AM, Tsuang MT: A DSM-III family study of the nonschizophrenic psychotic disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:1098–1105Google Scholar

12. Maier W, Lichtermann D, Minges J, Hallmayer J, Heun R, Benkert O, Levinson DF: Continuity and discontinuity of affective disorders and schizophrenia: results of a controlled family study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:871–883Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:773–782Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB, Spitzer RL, Davies M, Borus J, Howes MJ, Kane J, Pope HG, Rounsaville B, Wittchen H-U: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID), II: multisite test-retest reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:630–636Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Faraone SV, Blehar M, Pepple J, Moldin SO, Norton J, Nurnberger JI, Malaspina D, Kaufmann CA, Reich T, Cloninger CR, DePaulo JR, Berg K, Gershon ES, Kirch DG, Tsuang MT: Diagnostic accuracy and confusability analyses: an application to the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies. Psychol Med 1996; 26:401–410Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Martin RL, Cloninger CR, Guze SB, Clayton PJ: Frequency and differential diagnosis of depressive syndromes in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1985; 46:9–13Medline, Google Scholar

17. McGlashan TH, Carpenter WT Jr: Postpsychotic depression in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33:231–239Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Siris SG: Diagnosis of secondary depression in schizophrenia: implications for DSM-IV. Schizophr Bull 1991; 17:75–98Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Gershon ES, DeLisi LE, Hamovit J, Nurnberger JI Jr, Maxwell ME, Schreiber J, Dauphinais D, Dingman CW II, Guroff JJ: A controlled family study of chronic psychoses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:328–337Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Maj M: Lithium prophylaxis of schizoaffective disorders: a prospective study. J Affect Disord 1988; 14:129–135Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Bouman TK, Kampen JGN, Ormel J, Slooff CJ: The effectiveness of lithium prophylaxis in bipolar and unipolar depressions and schizoaffective disorders. J Affect Disord 1986; 11:275–280Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Mattes JA, Nayak D: Lithium versus fluphenazine for prophylaxis in mainly schizophrenic schizo-affectives. Biol Psychiatry 1984; 19:445–449Medline, Google Scholar

23. Brewerton TD, Reus VJ: Lithium carbonate and l-tryptophan in the treatment of bipolar and schizoaffective disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:757–760Link, Google Scholar

24. Goode DJ, Manning A: A comparison of bupropion alone and with haloperidol in schizoaffective disorder, depressed type. J Clin Psychiatry 1983; 44:253–255Medline, Google Scholar

25. Kufferle B, Lenz G: Classification and course of schizo-affective psychoses: follow-up of patients treated with lithium. Psychiatr Clin (Basel) 1983; 16:169–177Medline, Google Scholar

26. Carman JS, Bigelow LB, Wyatt RJ: Lithium combined with neuroleptics in chronic schizophrenic and schizoaffective patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1981; 42:124–128Medline, Google Scholar

27. Biederman J, Lerner Y, Belmaker RH: Combination of lithium carbonate and haloperidol in schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:327–333Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Brockington IF, Kendell RE, Kellett JM, Curry SH, Wainwright S: Trials of lithium, chlorpromazine and amitriptyline in schizoaffective patients. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:162–168Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Okuma T, Yamashita I, Takahashi R, Itoh H, Kurihara M, Otsuki S, Watanabe S, Sarai K, Hazama H, Inanaga K: Clinical efficacy of carbamazepine in affective, schizoaffective and schizophrenic disorders. Pharmacopsychiatry 1989; 22:47–53Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Okuma T, Yamashita I, Takahashi R, Itoh H, Otsuki S, Watanabe S, Sarai K, Hazama H, Inanaga K: A double-blind study of adjunctive carbamazepine versus placebo on excited states of schizophrenic and schizoaffective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989; 80:250–259Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Ries RK, Wilson L, Bokan JA, Chiles JA: ECT in medication-resistant schizoaffective disorder. Compr Psychiatry 1981; 22:167–173Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Müller-Siecheneder F, Müller MJ, Hillert A, Szegedi, A, Wetzel H, Benkert O: Risperidone versus haloperidol and amitriptyline in the treatment of patients with a combined psychotic and depressive syndrome. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1998; 18:111–120Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Keck PE Jr, Wilson DR, Strakowski SM, McElroy SL, Kizer DL, Balistreri TM, Holtman HM, Depreist M: Clinical predictors of acute risperidone response in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorders and psychotic mood disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56:466–470Medline, Google Scholar

34. Banov MD, Zarate CA, Tohen M, Scialabba D, Wines JD, Kolbrener M, Kim J, Cole JO: Clozapine therapy in refractory affective disorders: polarity predicts response in long-term follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry 1994; 55:295–300Medline, Google Scholar

35. Ceskova E, Svetska J: Double-blind comparison of risperidone and haloperidol in schizophrenic and schizoaffective psychoses. Pharmacopsychiatry 1993; 26:121–124Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. McElroy SL, Dessain EC, Pope HG Jr, Cole JO, Keck PE Jr, Frankenberg FR, Aizley HG, O’Brien S: Clozapine in the treatment of psychotic mood disorders, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52:411–414Medline, Google Scholar

37. Naber D, Hippius H: The European experience with use of clozapine. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990; 41:886–890Abstract, Google Scholar

38. Tollefson GD, Sanger TM, Lu Y: Depressive signs and symptoms in schizophrenia: a prospective blinded trial of olanzapine and haloperidol. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55:250–258Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Marder SR, Davis JM, Chouinard G: The effects of risperidone on the five dimensions of schizophrenia derived by factor analysis: combined results of the North American trials. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58:538–546Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Hogarty GE, McEvoy JP, Ulrich RF, DiBarry AL, Bartone P, Cooley S, Hammill K, Carter M, Munetz MR, Perel J: Pharmacotherapy of impaired affect in recovering schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52:29–41Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Siris SG, Bermanzohn PC, Mason SE, Shuwall MA: Maintenance imipramine therapy for secondary depression in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:109–115Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Dufresne RL, Valentino D, Kass DJ: Thioridazine improves affective symptoms in schizophrenic patients. Psychopharmcol Bull 1993; 29:249–255Medline, Google Scholar

43. Kramer MS, Vogel WH, DiJohnson C, Dewey DA, Sheves P, Cavicchia S, Litle P, Schmidt R, Kimes I: Antidepressants in “depressed” schizophrenic inpatients: a controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989; 46:922–928Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Dufresne RL, Kass DJ, Becker RE: Bupropion and thiothixene vs placebo and thiothixene in the treatment of depression in schizophrenia. Drug Dev Res 1988; 12:259–266Crossref, Google Scholar

45. Lerner Y, Mintzer Y, Schestatzky M: Lithium combined with haloperidol in schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry 1988; 153:359–362Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Siris SG, Morgan V, Fagerstrom R, Rifkin A, Cooper TB: Adjunctive imipramine in the treatment of postpsychotic depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44:533–539Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Becker RE: Implications of the efficacy of thiothixene and a chlorpromazine-imipramine combination for depression in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:208–211Link, Google Scholar

48. Johnson DAW: A double-blind trial of nortriptyline for depression in chronic schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1981; 139:97–101Crossref, Google Scholar

49. Kurland AA, Nagaraju A: Viloxazine and the depressed schizophrenic: methodological issues. J Clin Pharmacol 1981; 21:37–41Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Waehrens J, Gerlach J: Antidepressant drugs in anergic schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1980; 61:438–444Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Prusoff BA, Williams DH, Weissman MM, Astrachan BM: Treatment of secondary depression in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:569–575Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Singh AN, Saxena B, Nelson HL: A controlled clinical study of trazodone in chronic schizophrenic patients with pronounced depressive symptomatology. Curr Ther Res 1978; 23:485–501Google Scholar

53. Hayes SG: Long-term use of valproate in primary psychiatric disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1989; 50(March suppl):35–39Google Scholar

54. McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr, Pope HG Jr: Sodium valproate: its use in primary psychiatric disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1987; 7:16–24Medline, Google Scholar

55. Puzynski S, Klosiewicz L: Valproic acid amide as a prophylactic agent in affective and schizoaffective disorders. Psychopharmacol Bull 1984; 20:151–159Medline, Google Scholar

56. Schaff MR, Fawcett J, Zajecka JM: Divalproex sodium in the treatment of refractory affective disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54:380–384Medline, Google Scholar

57. Chouinard G, Annable L, Serrano M, Albert JM, Charette R: Amitriptyline-perphenazine interaction in ambulatory schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1975; 32:1295–1307Google Scholar

58. Meltzer HY, Okayli G: Reduction of suicidality during clozapine treatment of neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia: impact on risk-benefit assessment. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:183–190Link, Google Scholar

59. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154(April suppl)Google Scholar

60. Small JG, Kellams JJ, Milstein V, Moore J: A placebo-controlled study of lithium combined with neuroleptics in chronic schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1975; 132:1315–1317Google Scholar

61. Growe GA, Crayton JW, Klass DB, Evans H, Strizich M: Lithium in chronic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1979; 136:454–455Medline, Google Scholar

62. Johnson G: Differential response to lithium carbonate in manic-depressive and schizoaffective disorders. Dis Nerv Syst 1970; 13:613–615Google Scholar

63. Prien RF, Cafe EM, Klett JC: A comparison of lithium carbonate and chlorpramazine in the treatment of excited schizoaffectives. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1972; 27:182–189Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM: New developments in the pharmacologic treatment of schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57(suppl 9):41–48Google Scholar