Body Weight and Leptin Plasma Levels During Treatment With Antipsychotic Drugs

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Leptin is produced by fat cells and is presumed to signal the size of the adipose tissue to the brain. The authors investigated whether antipsychotic drugs that often induce weight gain affect circulating levels of leptin. METHOD: Weight, body mass index, and leptin plasma level were measured weekly over 4 weeks in psychiatric inpatients who received clozapine (N=11), olanzapine (N=8), haloperidol (N=13), or no psychopharmacological treatment (N=12). RESULTS: In patients receiving clozapine or olanzapine, significant increases in weight, body mass index, and leptin level were found, whereas these measures remained stable in patients who received haloperidol or no pharmacological treatment. CONCLUSIONS: Weight gain induced by clozapine or olanzapine appears to be associated with an increase in leptin level that cannot be attributed to dietary changes upon hospitalization.

Weight gain frequently occurs during treatment with clozapine (1) or olanzapine (2) and sometimes limits treatment compliance. Clozapine has been shown to increase circulating levels of leptin (3), a hormone produced by fat cells that is thought to signal the size of the adipose tissue to the brain. Mice and humans deficient in leptin are obese (4, 5). In ob/ob mice, leptin administration reduces food intake and weight (6, 7), indicating a role for this hormone in weight regulation. In humans, circulating leptin level correlates positively with body mass index; patients with anorexia nervosa, for example, have low leptin levels that increase in parallel to weight during treatment (8).

To explore the pathophysiology of weight gain during antipsychotic treatment, we longitudinally investigated weight, body mass index, and leptin level in patients treated with clozapine or olanzapine. In addition, we included a group of patients treated with haloperidol, which is known to induce only minor changes in weight (2). To control for the effect of minor dietary changes upon hospitalization, we also investigated patients who did not receive any pharmacological treatment.

METHOD

Consecutively admitted inpatients fulfilling the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for a schizophrenic disorder were assigned according to clinical decisions to monotherapy with clozapine (N=11), olanzapine (N=8), or haloperidol (N=13). The clozapine group comprised seven women and four men, whose mean age was 37 years (SD=19). In the olanzapine group there were five women and three men, and their mean age was 26 years (SD=6). The haloperidol group contained seven women and six men, and their mean age was 36 (SD=16). The mean doses (in milligrams per day) during weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, were as follows: clozapine—85 (SD=50), 145 (SD=63), 199 (SD=80), and 251 (SD=117); olanzapine—11 (SD=3), 13 (SD=3), 13 (SD=3), and 14 (SD=4); haloperidol—5 (SD=3), 5 (SD=3), 5 (SD=3), and 6 (SD=3). Twelve patients (seven women and five men; mean age=30, SD=12) suffering from various psychiatric disorders other than schizophrenia received no psychopharmacological treatment. The absence of medication was due either to diagnostic purposes (N=4) or to the fact that the patients were treated with behavioral psychotherapy exclusively (N=8). All patients received a standard hospital diet. After complete description of the study, all patients gave informed written consent to participate in the investigation, which had been approved by an independent ethics committee.

Weight was assessed at baseline and weekly thereafter. The body mass index was calculated by dividing the weight (in kilograms) by the squared height (in meters). The plasma levels of leptin were assessed by using radioimmunoassay (DRG Instruments, Marburg, Germany). The limit of detection was 0.5 ng/ml, and the intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 7% and 9%, respectively. For statistical analysis, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) for repeated measures was used. Post hoc comparisons were performed by tests with contrasts. As the nominal level of significance an alpha level below 0.05 was accepted and corrected according to Bonferroni for the post hoc tests. To account for baseline differences in weight, body mass index, and leptin level between groups, all values were divided by the mean at baseline for the respective treatment group before statistical analysis.

RESULTS

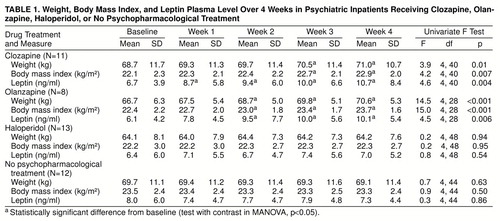

Analysis of variance revealed a significant overall treatment-by-time interaction (averaged Wilks"s multivariate test of significance: F=1.9, df=36, 476, p=0.001). Weight (F=4.4, df=12, 160, p<0.05), body mass index (F=4.6, df=12, 160, p<0.05), and leptin plasma level (F=2.3, df=12, 160, p<0.05) all contributed significantly to this interaction term.

As can be seen from table 1, clozapine and olanzapine treatment significantly increased weight, body mass index, and plasma leptin level. In the clozapine-treated group, leptin plasma level was significantly increased from baseline already at the end of the first treatment week; effects on body mass index and weight were evident from the third week onward. In the patients treated with olanzapine, plasma leptin level, weight, and body mass index were significantly increased from baseline starting at the end of the second week of treatment. MANOVA did not reveal a significant difference between the clozapine- and olanzapine-treated patients in the time course of any of the variables assessed.

In the drug-free patients and those treated with haloperidol, weight, body mass index, and leptin level showed no significant changes across time. MANOVA did not reveal a significant difference between these two groups in the time course of any of the variables assessed.

DISCUSSION

The present study confirms that clozapine-induced weight gain is associated with an increase in circulating leptin level (3). Moreover, we showed that olanzapine has similar effects, whereas weight, body mass index, and leptin level remain stable in patients receiving haloperidol or no psychopharmacological treatment. Therefore, the increases in weight and leptin level induced by clozapine and olanzapine cannot be explained by dietary changes upon hospitalization.

It has been shown that 75% of patients treated with clozapine report an increased desire to eat, and some patients report binge eating (3), suggesting that overeating leads to weight gain. Although we did not gather the respective information in the present study, it is likely that overeating underlies olanzapine-induced weight gain as well. Hence, the most probable reason for clozapine- and olanzapine-induced increases in leptin levels are overeating and weight gain. These may be due to the drugs’ effects on various neurotransmitter systems involved in the regulation of appetite (1–3). Alternatively, clozapine and olanzapine might reduce the feedback sensitivity of the CNS to the leptin signal, thus leading to a cascade of increased appetite, leptin secretion, and weight gain.

Apart from its involvement in the regulation of appetite, leptin has CNS effects such as blunting of stress responses (9). Because weight gain has some predictive value for a positive response to clozapine treatment (1, 10), it seems worthwhile to investigate leptin levels and psychopathology in parallel to test the hypothesis that leptin mediates the beneficial effects of neuroleptic treatment.

Received March 26, 1998; revision received July 24, 1998; accepted Aug. 18, 1998. From the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry. Address reprint requests to Dr. Pollm�cher, Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry, Kraepelinstrasse 10, 80804 Munich, Germany; [email protected] (e-mail). The authors thank Ms. Irene Gunst and Ms. Gabriele Kohl for technical assistance, Dr. Alexander Yassouridis for statistical advice, and Dr. Johannes Hebebrand for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

|

1. Bustillo JR, Buchanan RW, Irish D, Breier A: Differential effect of clozapine on weight: a controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153:817–819Link, Google Scholar

2. Beasley CM Jr, Tollefson G, Tran P, Satterlee W, Sanger T, Hamilton S: Olanzapine versus placebo and haloperidol: acute phase results of the North American double-blind olanzapine trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 1996; 14:111–123Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Br�mel T, Blum WF, Ziegler A, Schulz E, Bender M, Fleischhaker C, Remschmidt H, Krieg J-C, Hebebrand J: Serum leptin levels increase rapidly after initiation of clozapine treatment. Mol Psychiatry 1998; 3:76–80Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Campfield LA, Smith FJ, Guisez Y, Devos R, Burn P: Recombinant mouse ob protein: evidence for a peripheral signal linking adiposity and central neural networks. Science 1995; 269:546–548Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Montague CT, Farooqi IS, Whitehead JP, Soos MA, Rau H, Wareham NJ, Sewter CP, Digby JE, Mohammed SN, Hurst JA, Cheetham CH, Earley AR, Barnett AH, Prins JB, Orahilly S: Congenital leptin deficiency is associated with severe early-onset obesity in humans. Nature 1997; 387:903–908Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Halaas JL, Gajiwala KS, Maffei M, Cohen SL, Chait BT, Rabinowitz D, Lallone RL, Burley SK, Friedman JM: Weight-reducing effects of the plasma protein encoded by the obese gene. Science 1995; 269:543–546Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Pelleymounter MA, Cullen MJ, Baker MB, Hecht R, Winters D, Boone T, Collins F: Effects of the obese gene product on body weight regulation in ob/ob mice. Science 1995; 269:540–543Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Hebebrand J, Blum WF, Barth N, Coners H, Englaro P, Juul A, Ziegler A, Warnke A, Rascher W, Remschmidt H: Leptin levels in patients with anorexia nervosa are reduced in the acute stage and elevated upon short-term weight restoration. Mol Psychiatry 1997; 2:330–334Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Heiman ML, Ahima RS, Craft LS, Schoner B, Stephens TW, Flier JS: Leptin inhibition of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in response to stress. Endocrinology 1997; 138:3859–3863Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Jalenques I, Tauveron I, Albuisson E, Audy V, Fleury-Duhamel N, Codert AJ: Weight gain as a predictor of long term clozapine efficiency. Clin Drug Invest 1996; 12:16–25Crossref, Google Scholar